Book Review: The St. Louis Commune of 1877: Communism in the Heartland by Mark Kruger

Douglas Lyons

WSWS.ORG

The St. Louis Commune of 1877: Communism in the Heartland, by Mark Kruger. 330 pages. October 2021. ISBN: 978-1-4962-2813-0

One of the most revolutionary events in American history is also one of the least known: In July 1877, the working class in St. Louis launched a general strike and seized power in the city, establishing a short-lived proletarian dictatorship. Led by the Workingmen’s Party of the United States (WP), a descendant of the First International, St. Louis workers elected an Executive Committee to direct the functions of government and oversee the economy for a brief day or two until the leadership vacillated and caved in the face of capitalist repression.

The St. Louis Commune of 1877 formed the revolutionary center of gravity of the spontaneous Great Railroad Strike, which started at the beginning of July and ended in September 1877. Ruthless wage cuts, unsafe working conditions, and unprecedented inequality triggered the uprising, which swept across the United States, coast to coast. Its scope and spontaneity rocked the very foundations of capitalist rule and ushered in a new epoch, with the working class stepping forward as a powerful force.

Book cover

This rich history is found in a new book on the subject, The St. Louis Commune of 1877: Communism in the Heartland, written by Mark Kruger, a retired professor who lives in the city. Kruger’s book is valuable. Little has been written on the St. Louis Commune since David Burbank’s Reign of the Rabble, published in 1966, a meticulous blow-by-blow narrative. The entire strike wave was covered by Robert Bruce in 1877: Year of Violence (1959) and Philip Foner in The Great Labor Uprising of 1877 (1977).

Kruger’s book is a rebuke against the most basic lie of American history: that there has been no class struggle or socialism in the United States. Just one decade after the Civil War, socialism found fertile soil in America as workers were thrown into massive, and often bloody, struggle against the capitalists. The American working class, though ethnically and racially diverse, bitterly fought to raise its living standards, and for basic workplace rights, against the bourgeoisie.

But the Commune cannot be entirely understood separated from the international influence of socialism and the revolutionary uprisings of the mid-19th century. Kruger’s success is placing it within this broader context: the 1848 revolutions in Europe, the First International and the Paris Commune, all of which had profound influence on American politics and society.

Kruger’s book has valuable lessons. It should find a working class audience at a time when socialism’s popularity is on the rise, capitalism is increasingly becoming a dirty word, and with the first strike wave in decades gathering force, uncorked by the COVID pandemic and the ruling class’s criminal profit-over-lives policy which has killed over 800,000 people in the United States and millions across the world.

Post-Civil War boom and inequality

Out of the destruction of chattel slavery in the Civil War a new era emerged. Kruger sets the stage with discussion of the trends of industrial development and its depressions, the poverty and oppression of the working class, the vileness and corruption of the rich, and the growth of the massive railroad industry.

American capitalism entered into unprecedented expansion. Between 1865 and 1873, industrial production grew by more than 75 percent. The railroad industry would lead the way, linking city and country together, birthing and—in objective terms—uniting a restive working class.

All the growth was not the work of the “invisible hand” of the market. The government offered lucrative public land grants, contracts and subsidies, passing the Pacific Railway Acts of 1862 and 1863. With government largesse the Transcontinental Railroad was completed in 1869. And with the anti-competitive fostering of state and federal government, the Pennsylvania Railroad would grow into the largest corporation in the world, Kruger writes.

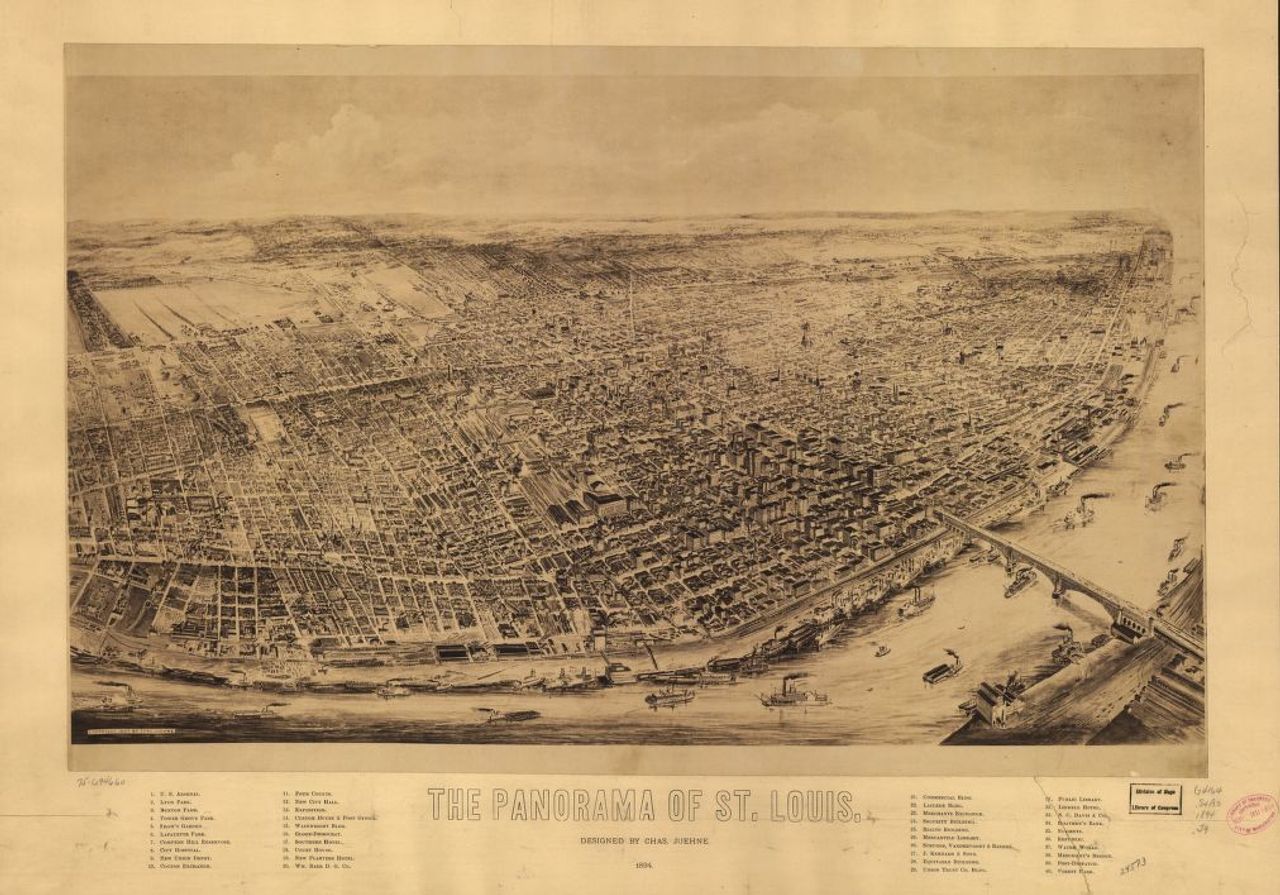

St. Louis, like many other cities, grew by leaps and bounds. Situated at the westernmost industrial portion of the country, St. Louis’ marquee location made it a potential gatekeeper for westward expansion. Vast sums of capital fed into the city in an effort to propel St. Louis to first place in a no-holds-barred race over competitors such as Chicago. John O’Fallon and James Lucas, two of the city’s richest capitalists, rushed to finance the Iron Mountain Railroad and adjacent industries such as passenger and railroad car manufacture, meatpacking and coal production. Notorious Robber Barons such as Jay Gould gobbled up railroad market share. Profits grew to stratospheric levels.

Gilded Age panorama of St. Louis

In the period known as the Gilded Age—a double entendre coined by Mark Twain— the bourgeoisie shamelessly pursued wealth and self-aggrandizement, flaunting status symbols. Kruger gives the example of William Vanderbilt, son of Cornelius, the tycoon of the New York Central Railway, who constructed a mansion in Midtown Manhattan mimicking the French Renaissance chateau. Its walls were decked out in Renaissance Italian tapestries depicting scenes from classical Greek and Roman mythology. A stained-glass window depicting King Henry VIII’s détente with Francis I of France underscored the embrace by the emerging financial oligarchy in America of the blood-soaked, filthy-rich monarchies in Europe.

But this orgy of wealth was rudely interrupted by crises. In 1873, a global financial meltdown shocked the United States, and then the world, sending over half of railroad companies into receivership by 1876. Railroad stocks fell 60 percent. The depression lasted through the remainder of the decade, immiserating society and sharpening working class anger.

The World in America: The Forty-Eighters, the First International and the Paris Commune

The considerable strength of Kruger’s book is his careful attention to international influences on American workers. The “American working class,” Kruger shows, has always been highly international.

An enormous share of the working class was comprised of first- or second-generation immigrants. Among them were thousands of radical German workers, many of them political refugees from the 1848 revolutions in Europe. They contributed a powerful and healthy impulse to American politics. Kruger shows that these immigrants contributed decisively to the victory of the Union in Missouri during the Civil War—the Germans were overwhelmingly hostile to slavery—and he argues that these political exiles were indispensable to the general strike and Commune, providing “the philosophy and leadership.”

Sixty-three thousand Germans immigrated to the US in 1848, increasing to about 230,000 within six years. In St. Louis, one-third of the population had been born in Germany and the adult population consisted of 77 percent immigrants, mostly from Germany and Ireland. German newspapers proliferated, totaling 80 percent of all foreign-language newspapers by 1880. And St. Louis was not alone. Milwaukee, Chicago, Cincinnati and other major American cities had large German populations.

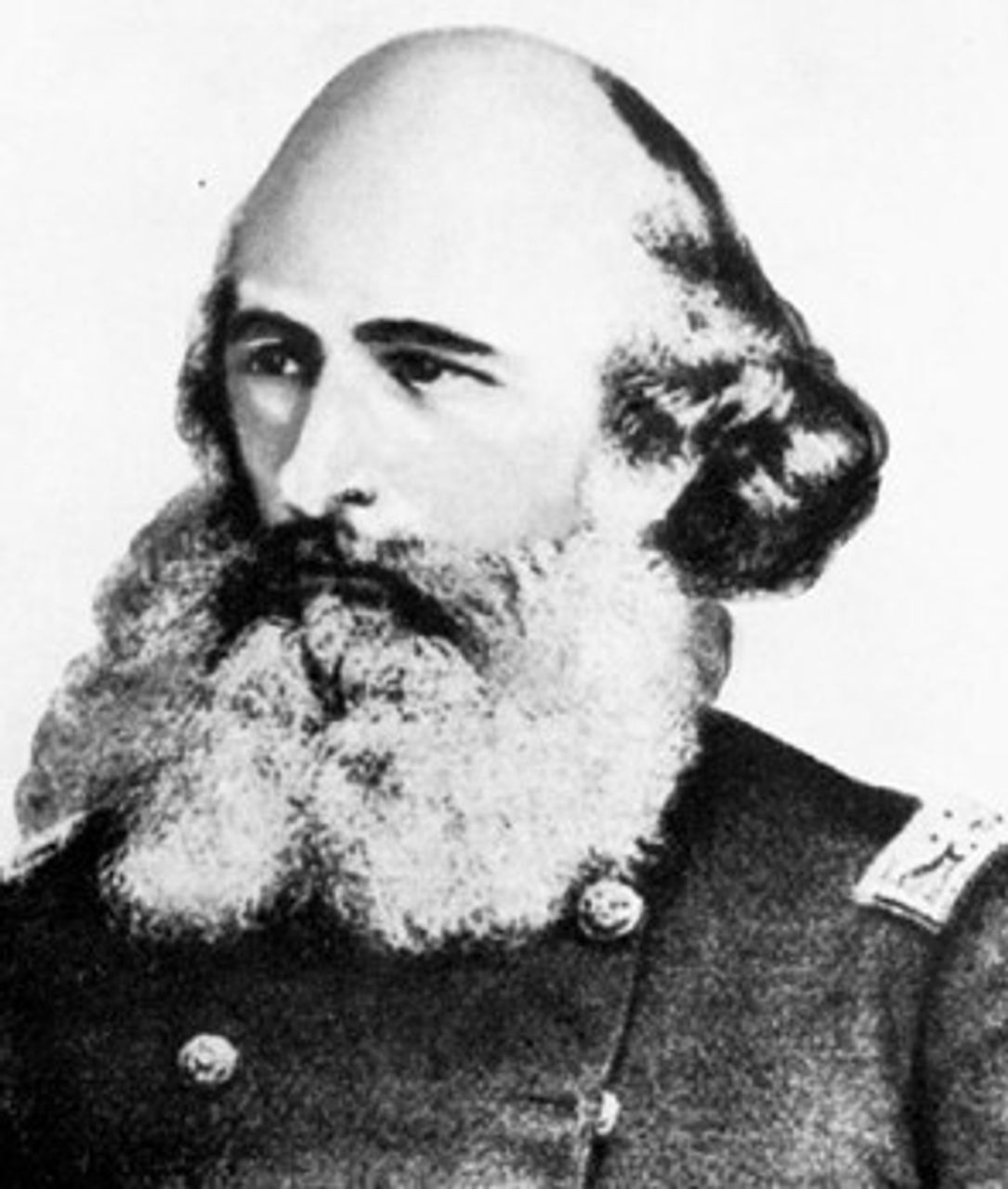

The most renowned German immigrant in St. Louis was Joseph Weydemeyer, a friend of Marx and the founder of the American Workers League, who became colonel of the Forty-First Missouri Infantry for the Union army in the Civil War. Credited with introducing socialism into the city, Weydemeyer moved to St. Louis in 1861 by suggestion of Friedrich Engels, who thought socialist ideas would resonate in the large German population. He edited a German-language newspaper, Die Neue Zeit, and was elected auditor of St. Louis County, advocating for the eight-hour workday. Weydemeyer died in 1866 in a cholera epidemic.

Joseph Weydemeyer

The banner of scientific socialism then shifted to the American section of a new organization of socialists and militant workers: the International Workingmen’s Association, or the First International, which had held its first Congress the same year as Weydemeyer’s death.

Events with the First International in Europe impacted American developments. In 1872 at the Hague Congress of the First International, after the irreparable split between Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels on the one side and the anarchists led by Mikhail Bakunin on the other, Engels introduced a motion to move the General Council to New York for fear of a Bakuninist coup. Friedrich Sorge, a German immigrant and leader of the German section of the International in New York, took on day-to-day management of the organization.

Friedrich Sorge

Saving it from a premature demise would pay historic dividends to the working class movement in the United States.

Kruger writes that at the First International’s last Congress in 1876, dubbed the Unity Congress, 19 sections formed a new Marxist political party, the Workingmen’s Party USA. Albert Currlin, a baker and future leader of the Commune, marshalled the St. Louis delegation to this landmark achievement. WP members were elected to office in Chicago, Milwaukee and Cincinnati, publishing 24 newspapers in total.

Despite a short lifespan in the United States, dissolving in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in July 1876, the First International sowed seeds in the young American labor movement. In 1871, it had a total of 19 sections, jumping to 35 by the end of the year. St. Louis had German, English, French and Czech language sections.

According to Kruger, the First International “was the first time workers had organized on an international scale,” disseminating radical ideas and spearheading the international fight for the eight-hour workday. The American branch, an eclectic mix of Marxists, anarchists, reformists and followers of Ferdinand Lassalle, supported strikes of over 100,000 workers in 32 different trades across the East and Midwest.

The Paris Commune, another seminal episode inspiring the international working class, germinated radical ideas among American workers. The First International, which had 17 members elected to the leadership of the Commune on March 28, 1871, brought this experience into its cadre and the international working class, notably in Marx’s incisive pamphlet, The Civil War in France, which saw several editions within the first year and was translated into many different languages. Communist workers and members of the International supported the Commune and played an active role in its consummation, manning the barricades against the French army and the butcher Adolphe Thiers—who would murder over 20,000 Parisians.

The Paris Commune also terrorized the American capitalists, sending them into panic and bloodlust. The pro-Democratic Party New York Herald ranted, “Make Paris a heap of ruins if necessary, let its streets be made to run rivers of blood, let all within it perish, but let the government maintain its authority and demonstrate its power.” In similar news articles and political speeches across the country, the American ruling class let workers know that it fully embraced Thiers’ methods.

The Great Railroad Strike and the St. Louis Commune of 1877

The last chapters bring together these strands in 1877 St. Louis, where what started as a labor dispute against wage cuts and unsafe conditions transformed into a revolutionary uprising of the working class. In the author’s words, “the strike that began over bread-and-butter issues expanded its focus and took on the elements of class warfare.”

American railroad magnates in May and June 1877 simultaneously slashed wages for the second or third time since the start of the depression—wage reductions totaling as much as 50 percent—despite raking in large profits and divvying up huge salary increases among managers and shareholders.

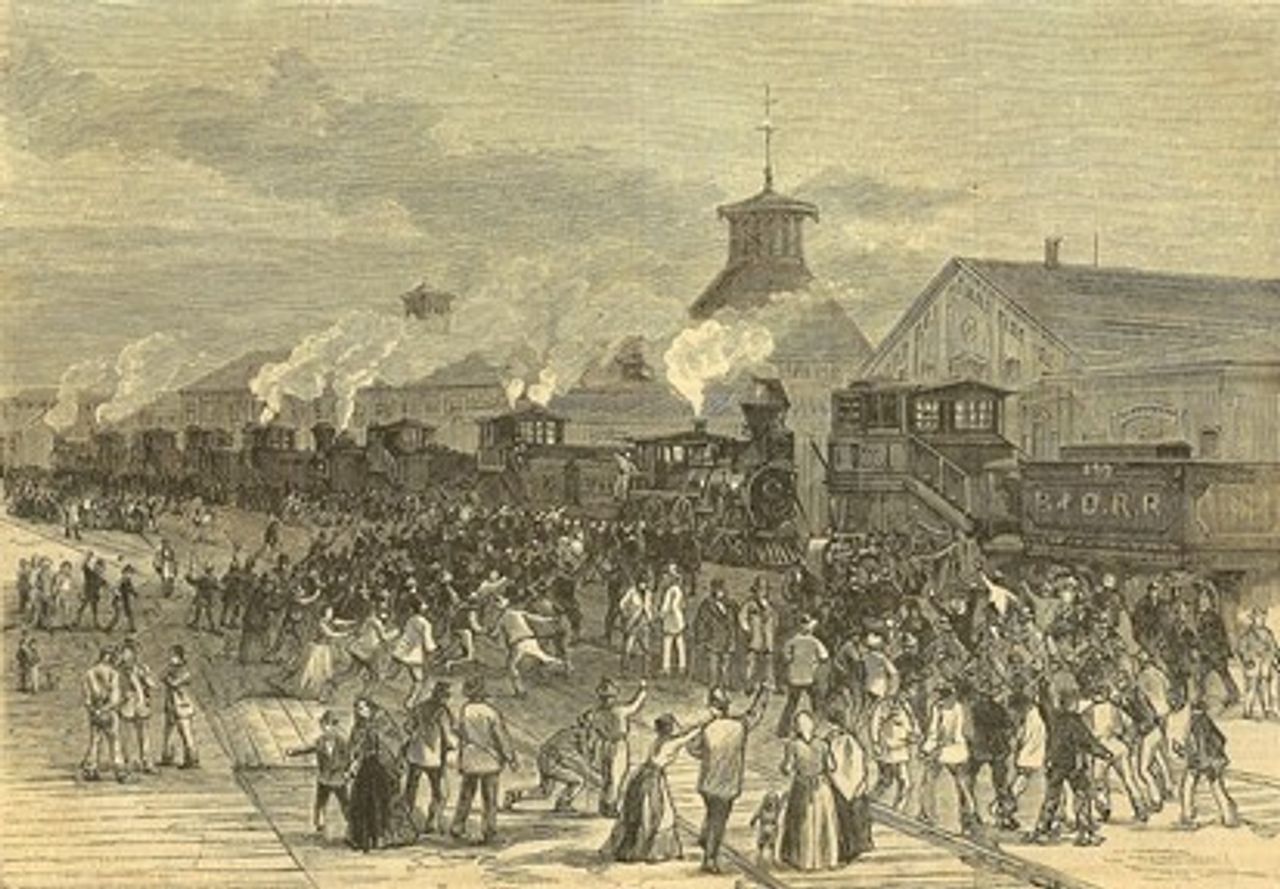

Workers blocking trains during the Great Railroad Strike in Martinsburg, West Virginia

Railroad workers refused to be beaten into poverty. The Great Railroad Strike erupted in Martinsburg, West Virginia, and Baltimore, Maryland, on July 16. Alternatively called the Great Uprising, it still stands out for its spontaneity, massive scope and ferocious working class solidarity.

The strike snowballed, seemingly of its own volition. In Baltimore, box makers, can makers and sawyers joined the strike, demanding their own wage increases. Miners and boatmen stopped trains in West Virginia, unemployed workers snubbed overtures to scab, and railroad property such as the B&O fell into the hands of workers. Coal miners joined in Pennsylvania. The strike swept north and south, east and west, reaching as far as California. Massive eruptions took place in West Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Ohio, New York, New Jersey, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Kentucky and Missouri. Kruger says by July 22, over 1 million workers went on strike.

Caught off guard at first, governors rushed to dispatch militias to decapitate the growing movement, but some refused to fire on their class brothers or were overpowered by the sheer number and willpower of the masses. President Rutherford B. Hayes sent in 3,000 federal troops to various locations. Violence rocked Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Chicago, Buffalo and Scranton, Pennsylvania. Hundreds were killed and wounded.

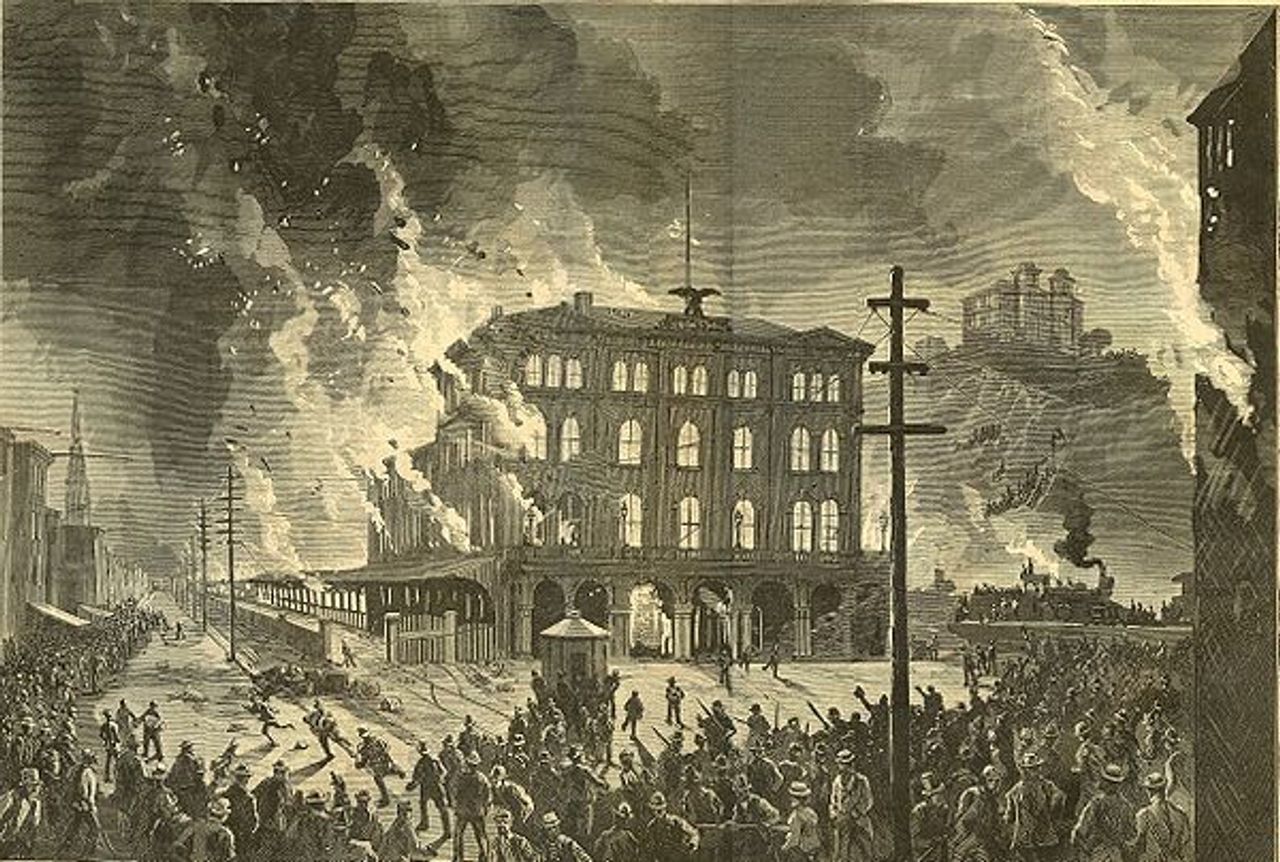

Burning of the Union Depot in Pittsburgh, during Great Railroad Strike

The bourgeois press smeared the workers as “blood-thirsty communists,” “Ill-dressed, evil-looking, hard-featured, beetle-browed, grimy unkempt men…scowling faces.” And it warned that “in St. Louis, a branch [the WPUSA] of the [Paris] Commune…conspires for the overthrow of the Governments of the world.”

The Workingmen’s Party, itself blindsided, had to catch up with events, throwing its weight behind the movement. On July 22, Philip Van Patten, the WP Corresponding Secretary, called on all sections of the party to support the strike, advocating demands such as an eight-hour day and nationalization of the railroad and telegraph industries.

It would be in St. Louis, however, where the 1,000-member-strong WP played the most consequential factor, as Kruger’s work shows.

The WP hurried to organize meetings to win over the movement and give it direction. At one meeting, Peter Lofgreen, financial secretary of the WP’s English-speaking section, Albert Currlin, and Henry F. Allen, a utopian socialist and sign painter by trade, all members of the Executive Committee of the WP, demanded a return to the 1873 pay scale, amounting to a 50 percent raise, as well as nationalization.

On Monday, July 23, the WP called another mass meeting, bolstering its leadership credentials of the strike and steering the discussion to the crux of the problem, the capitalist system. Setting up three speakers’ stands so the enormous crowd could hear, WP members and workers called for revolution. Lofgreen asked, “Why should we allow ourselves to be trodden upon by a few monopolists, who having the reins of government in their hands, are using the organized assassins to crush us?” Cheers exploded.

The crowd roared when another speaker had said that the working class was taxed “to sustain a standing army to be used to repel invasions by foreign powers, but the army is now used as a tool to oppress and slaughter innocent men, women, and children.” Another decried, “Why this state of things? Because it’s so, according to the law. Well, if that’s law, then d—n the law. [Prolonged cheers]. If that is the rule that governs society, then the sooner it is broken, the better.”

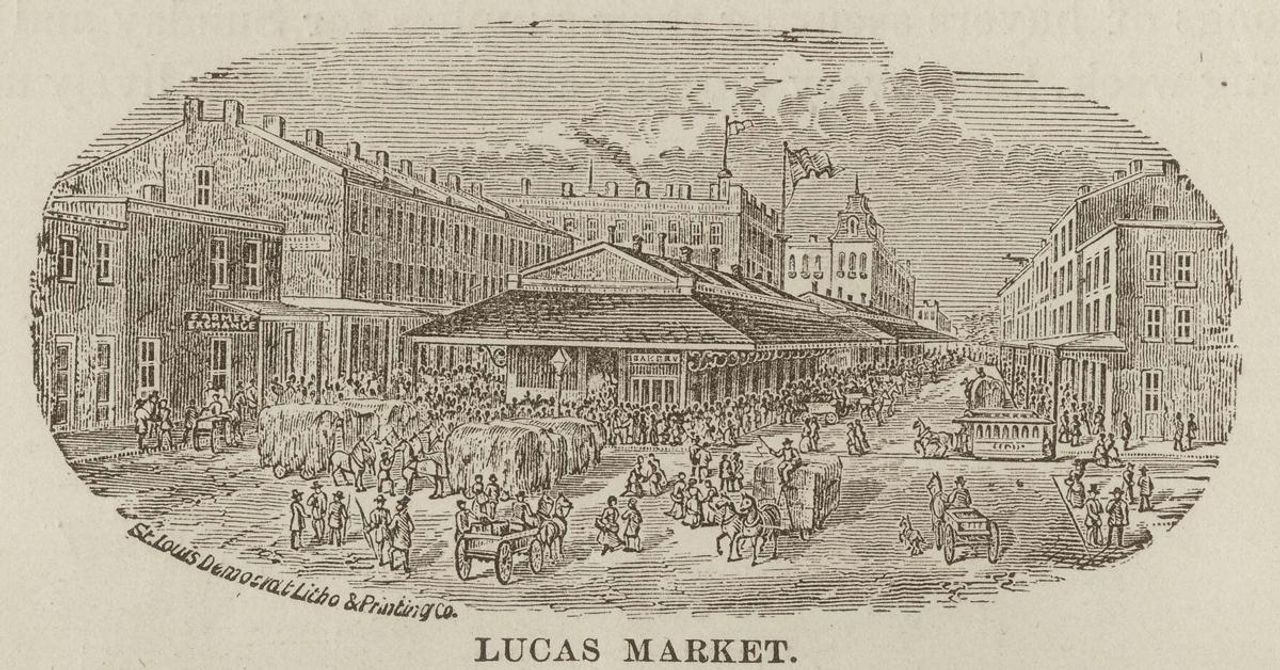

Lucas Market Square, where Workers Party addressed mass meetings during St. Louis Commune

Meanwhile the city’s elite and two former Union and Confederate generals organized the Committee of Public Safety, whose new purpose was to put the working class under the jackboot of the bourgeoisie. Federal forces entered the city bringing manpower, arms and ammunition. A bloodbath was being prepared.

The high-water mark of the strike wave was Wednesday, July 25. The very next day the steam had dissipated. The Commune fell without much of a fight. Its leadership was rounded up and sent to jail in St. Louis and East St. Louis, located across the Mississippi River in Illinois. By Sunday, July 29, the ruling class regained the city. After the Commune’s fall, the city’s elite created the Veiled Prophet organization, staging yearly parades celebrating the victory over the strike.

Kruger is somewhat speculative about the reasons for the St. Louis Commune’s defeat. The bulk of his analysis seems to imply that it was owed to a lack of decisiveness in the leadership, which never really attempted to conquer power. He also refers to the exploitation of racial and ethnic tensions among black, native white, German and Irish workers.

Though race and nationality divided the population, this was partly overcome during the strike, in opposition to the racist attitudes of some leaders such as Currlin. For instance, the Executive Committee of the WPUSA with several hundred multi-racial, multi-ethnic strikers and supporters, demanded that wages of boatmen, all of whom were black, be raised by 50 percent, the same amount railroad workers demanded. Black and white workers, armed with clubs, encouraged workers to join the strike, shutting down several workplaces. At one mass meeting a black worker asked the crowd whether or not white workers stand with him: the crowed responded, “We will!”

In hindsight, it seems too much to have asked of history that there should have been a successful proletarian revolution in the US in 1877. The class struggle was new and powerful, but workers had accumulated little experience. Across the country, powerful strikes erupted without political leadership. In this sense, the success or failure of the St. Louis Commune can be attributed above all to the insufficient political consciousness of the working class on a national scale, even though in St. Louis the WP attempted to elevate this consciousness and reveal the necessity in seizing political power from the capitalist class. Though St. Louis was an important city, it was by no means comparable to the role of Paris in French national life.

What is astonishing is how far things went in 1877, especially in St. Louis. At its conclusion, none of the demands that workers had been fighting for were met, but the revolutionary potential of the American working class, though immature in its theoretical and organizational development, was in perfect display.

Over 140 years have passed since the events of 1877, but the experience still holds crucial lessons for the working class today as it confronts a capitalist system in terminal decline. It is imperative that before the next revolutionary outbreak happens, which will be international in scale, that its lessons are assimilated. The events of 1877, and the St. Louis Commune, show the enormous industrial power of the working class. But they also reveal the decisive nature of prepared revolutionary leadership, the necessity of raising the political consciousness of workers against the false promises of the ruling class, and the need for class unity in opposition to all efforts to divide workers along racial and ethnic lines.