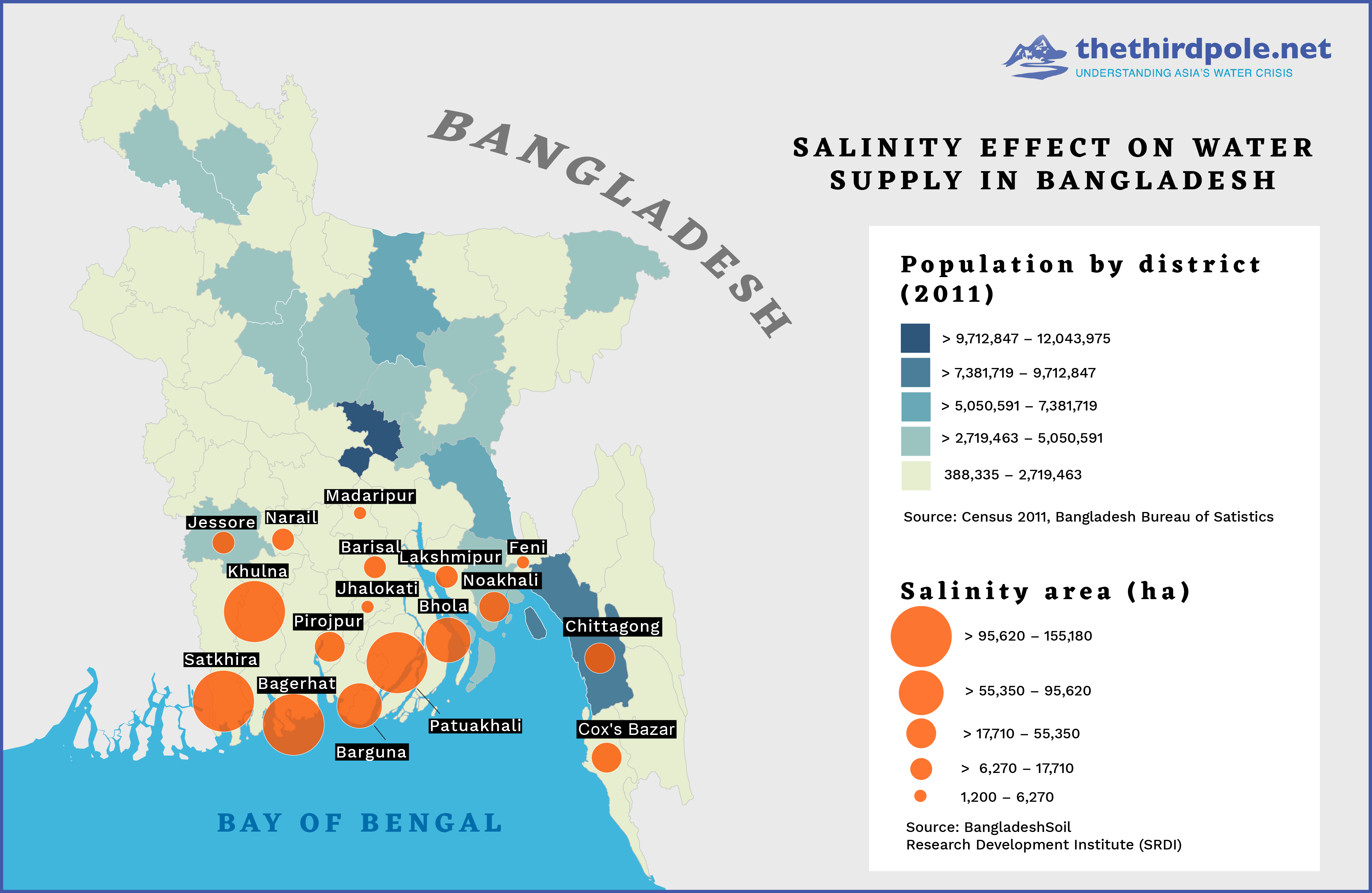

Recognising that waste is central, not peripheral, to everything we design, make and do is key to transforming the future

Moving scrap, including computers keyboards and other e-waste, at the former Agbogbloshie dump in Ghana in March 2009. Photo by Andrew McConnell/Panos

Justin McGuirk is the chief curator at the Design Museum in London. His writing has appeared in The New Yorker, The Guardian and e-flux, among many others. He is the author of Radical Cities: Across Latin America in Search of a New Architecture (2014).

Edited by Sally Davies

3,200 words

The opposition between ‘nature’ and ‘culture’ is problematic for many reasons, but there’s one that we rarely discuss. The ‘nature vs culture’ dualism leaves out an entire domain that properly belongs to neither: the world of waste. The mountains of waste that we produce every year, the torrents of polluting effluent, the billions of tonnes of greenhouse gases, the new cosmos of microplastics expanding through our oceans – none of this has ever been entered into the ledger under ‘culture’. Of all the products of human hands, it’s the oeuvre that no one wants to own, discuss or preferably even see. Yet it can’t be assimilated into ‘nature’ either, at least not in the way that pre-industrial waste has been for millennia. This new, ‘improved’ waste is incompatible with Earth – too chemical, too durable, too noxious and, ultimately, too voluminous.

Waste is precisely what dissolves the distinction between nature and culture. Today, when the very weather is warped by the climate crisis, and plankton thousands of metres deep have intestinal tracts full of microplastics, the idea of a nature that is pristine or untouched is delusional. Nature and waste have fused at both planetary and microbiological scales. Similarly, waste is not merely a byproduct of culture: it is culture. We have produced a culture of waste. To focus our gaze on waste is not an act of morbid negativity; it is an act of cultural realism. If waste is the mesh that entangles nature and culture, it’s necessarily the defining material of our time. We live in the Waste Age.

If we look at the material ages of human history, from the Stone Age and the Bronze Age through to the Steam Age and the Information Age, we get the illusory sense that hard things are dematerialising. In fact, the opposite is true. The Steam Age launched a great explosion of material goods that has mushroomed exponentially ever since, while statistics about our current rates of waste numb the mind. What does it mean to say that, by 2050, as much as 12 billion tonnes of plastic will have accumulated in landfills or the natural environment? What does it mean to observe that more than a million plastic bags are consumed every minute globally, and that this amounts to between 500 billion and 5 trillion a year? Such numbers present a seemingly precise quantification yet one that’s utterly ungraspable. The average person just translates them into ‘a shitload’.

This is where the naming of ages becomes useful. The Anthropocene, or the age of human-driven planetary change, helps to evoke the new geological layer we are forming, a new planetary crust composed of our fossil-fuel residues, bottle tops and cigarette butts. Could we imagine any more literal entanglement of nature and waste? Some prefer a more political definition, the Capitalocene, which points the finger at a specific economic system: capitalism. But to say that we live in a Waste Age is to acknowledge both its geological and economic dimensions. It is to acknowledge that culture produces not just architecture and ingenious devices, but also a million plastic bags a minute. It is to acknowledge that growth is entirely dependent on the relentless and ruthlessly efficient generation of waste.

Is this an ungenerous and pessimistic take on human activity in the 21st century? On the contrary. Invoking the Waste Age offers the opportunity for a radical shift in late-capitalist civilisation. Only by recognising the scale of the crisis can we reorient society and the economy towards less polluting modes of producing, consuming and living. The problem is that waste has always been a marginal issue, both literally and figuratively. It has been dumped in and on the peripheries, consigned to that mythical place called ‘away’. It has always been an ‘externality’, an unavoidable byproduct of necessary industrialisation. But it is now an internality – internal to every ecosystem and every digestive system from marine micro-organisms to humans. If waste truly were to be a central issue – brought into the heart of every conversation about how things are extracted, designed and disposed of – it would transform society beyond recognition. To invoke the Waste Age is to usher in the hope of a cleaner future.

Waste as a phenomenon is actually a relatively recent concept. It was only with the advent of the Industrial Revolution, and its massive stimulation of production, that the material byproducts of extraction and manufacturing began to accumulate in mountainous heaps. The modern idea of waste, then, is only 250 years old.

Contrary to what we might assume, wastefulness is not a natural human instinct – we had to be taught how to do it. Disposability was one of the great social innovations of post-war society in the United States. When the first disposable products became available in the 1950s, from TV-dinner meal trays to cocktail cups, consumers had to be persuaded that this magical new substance – plastic – was not too good to be thrown away. They had to be instructed in the advantages of the throwaway society. Corporations – in particular, the petrochemicals industry – spent many years and millions of dollars lobbying for the replacement of paper grocery bags with plastic ones. With the advent of supermarkets, and a help-yourself service culture, every product now had to be individually packaged to survive on the shelves. And with the full bloom of convenience culture and take-away everything, disposability reached its apogee.

Some observers were quick to disapprove. Vance Packard’s book The Waste Makers (1960) offered a searing critique of the midcentury US at the height of its consumerist pomp. He details at length the different forms of planned obsolescence, from products engineered to fail to those that are simply meant to be more desirable than last year’s model. And, at almost every level of society, it is understood that such obsolescence is a necessary feature of a healthy economy – from politicians to cynical businessmen, to disillusioned (but compliant) designers, to consumers who think it is their patriotic duty to shop and support the economy. The very idea of the ‘lifetime guarantee’ conjured up the spectre of unemployment and shuttered factories. The Waste Makers is an X-ray of the American way of life – a society that replaced scarcity with overabundance, force-fed on easy credit and urban sprawl. Packard sees the problem as largely ethical – his concern is moral decay and the ‘sell, sell, sell’ commercialisation of everyday life. Yet at no point does he envision an ecological catastrophe. Soon after, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962), about the devastating effects of agricultural pesticides, would start to alert people to this problem.

Waste is deliberately generated as the very metabolism behind economic growth

By 1950, the world was producing about 2 million tonnes of plastic each year. In 2019, it was 368 million tonnes, with more plastic produced in the past decade than ever before. Nearly half of all plastic waste (47 per cent) comes from packaging, while 13 per cent comes from textiles. As David Farrier writes in his book Footprints: In Search of Future Fossils (2020): ‘it is likely that every single piece of plastic ever produced and not incinerated still exists somewhere in some form’. It’s believed there are more than 5 trillion pieces of plastic in the world’s oceans, many in the gyre known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. In his novel The Peripheral (2014), William Gibson accelerates this diffuse mess into an island with its own city, a plastic landmass inhabited by transhuman ‘patchers’. It’s a darkly humorous piece of dystopian fiction, and one that grasps the fact that the plastics industry is in no mood to shrink. In fact, fossil-fuel companies, bracing themselves for a drop in petrol use, are gearing up to massively increase plastics production. And who will stop them?

To say that we live in the Waste Age is not to focus attention on an unpleasant but marginal problem; it’s to say that the production of waste is central to our way of life. Waste is deliberately generated as the very metabolism behind economic growth. And while the waste crisis and the climate crisis are not the same thing, waste is a major driver of climate change. Plastic production is the second-largest source of industrial greenhouse gases, and methane generated in landfills is another significant contributor.

But to invoke the Waste Age is also to claim that waste is one of the great material resources of our time. It acknowledges the tremendous untapped value in what we throw away. Take the tens of millions of tonnes of electronic scrap that we discard every year. Instead of recycling it, countries such as the UK have been shipping it to Ghana – where it used to amass in Agbogbloshie, a large informal settlement in the capital Accra. Although it has since been dismantled by the authorities, for years Agbogbloshie was at the heart of a complex, internationally connected local economy, where e-waste was mined for precious metals and valuable parts. The methods can be noxious – plastic wires burned to release the copper – but the principle is sound. Some estimate that by 2080 the largest metal reserves will not be underground but in circulation as existing products. About 7 per cent of the world’s gold supplies, for instance, are trapped inside electronics. Suddenly ‘above-ground mining’ starts to make sense.

You might think that I’m suggesting that recycling is the answer to this crisis. Far from it. Recycling rates are pathetically inadequate, and in many countries the system is essentially broken. The notion of recycling works to justify the production of more virgin plastics and other materials, as if it’s alright because they will be recycled, when they won’t. Recycling will play an important role in the transition to the new economy – whatever that looks like – but it’s not enough on its own.

Meanwhile, any attempts to blame consumers for the waste crisis or the failures of recycling are, at best, wide of the mark and, at worst, deeply cynical. This was illustrated when it emerged that, contrary to government claims, more than half of the plastic purportedly recycled in Britain had instead been shipped abroad to be dumped or incinerated. In 2020 alone, more than 200,000 tonnes of our ‘recycled’ plastic was dumped and burned in Turkey. What a mockery of the consumer labour that went into sorting and rinsing yoghurt pots and milk bottles.

Similarly, post-consumer waste is only a small part of the problem. When it comes to e-waste, by far the greatest percentage has already been produced before a device is even purchased: the mining and manufacturing processes generate quantities of waste that no amount of recycling can come close to remediating. Since most of this waste happens ‘upstream’, before shoppers put their hands in their pockets, the onus is on governments to legislate, just as they have on other issues in the past – from banning of chlorofluorocarbons in fridges to mandating tempered glass in car windscreens. Manufacturers, too, must shoulder their responsibilities, but they can’t be relied upon to do the right thing.

What role can and should designers play in all this? Design has been a driving forces behind our prodigious waste streams in the past century. As the handmaidens of commerce, designers have been complicit in the throwaway economy: manufacturing planned obsolescence, promoting convenience culture, entombing products in layers of seductive packaging. In short, they’ve been doing what designers do best – creating desire. Paradoxically, even when designers achieve a sense of permanence, it is illusory; the iPhone seemingly achieved the Platonic ideal of the smartphone, only to be replaced year after year because of software innovations and the need to stimulate new sales.

However, the culture of design is changing, and the outlook of young designers today is very different from that of their predecessors. Many have very little interest in producing more stuff, and are much more invested in understanding the extractive processes behind products and their afterlives. Shorn of blissful ignorance and only too alert to the mounting crisis around us, designers are reinventing themselves as material researchers, waste-stream investigators and students of global economic flows.

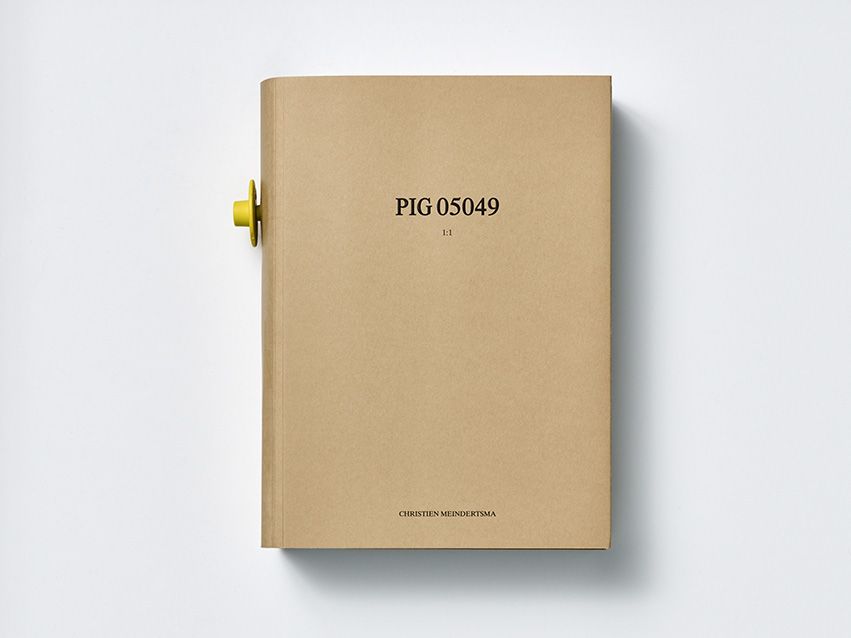

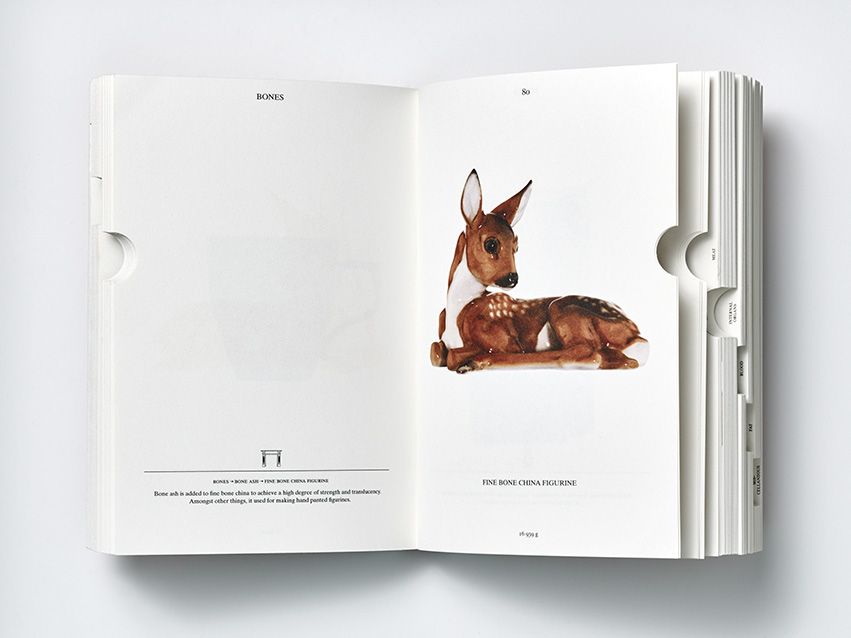

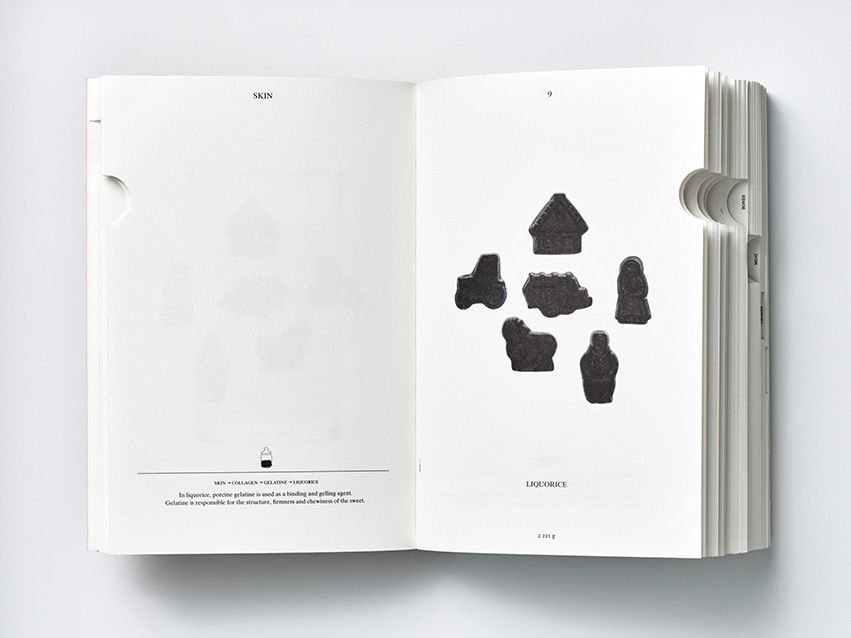

From pig to plate, and everything else. All images from the book PIG 05049 (2007) © and courtesy Christien Meindertsma

1 of 8

The Dutch designer Christien Meindertsma was at the forefront of this shift more than a decade ago with her book PIG 05049 (2007), which mapped all of the parts of a single pig to their destinations in shampoo, chewing gum, bullets and a host of other unexpected products. She has since investigated what remains in the ash from waste incinerators, how to recycle woollen jumpers, and the potential uses of ripped-up linoleum. Formafantasma, two Italian designers of the same generation, have conducted in-depth research into the recycling of electronic waste and the history of the timber industry. The studio’s Simone Farresin and Andrea Trimarchi now teach a course called Geo-Design at the Design Academy Eindhoven in the Netherlands that calls attention to the geopolitical forces shaping the design industry. For designers of this stripe, the physical object is no longer an end in itself but a vehicle towards understanding the complex systems that produce it, and the even more opaque systems that dispose of it.

The most sustainable building is the one that already exists, yet developers are incentivised to build anew

Interrogating these systems is vital for reducing waste and pollution at each stage of an object’s life, from extraction to decomposition. If every product was evaluated in terms of how much waste it generated or how brief its lifespan was likely to be, it would transform the discipline, and consumer behaviour along with it. In many cases, those objects would not be brought into being in the first place. But how can designers implement strategic change when they must fulfil the briefs of their paymasters? The last thing any manufacturer or politician wants is reduced production. Well, in that case, designers need to convince them.

The 2017 transformation of the social housing complex Cité du Grand Parc in Bordeaux in France by the architects Lacaton & Vassal. Photo by Laurian Ghinitoiu

Interior of an apartment’s ‘winter garden’ extension by Lacaton & Vassal. Photo by Laurian Ghinitoiu

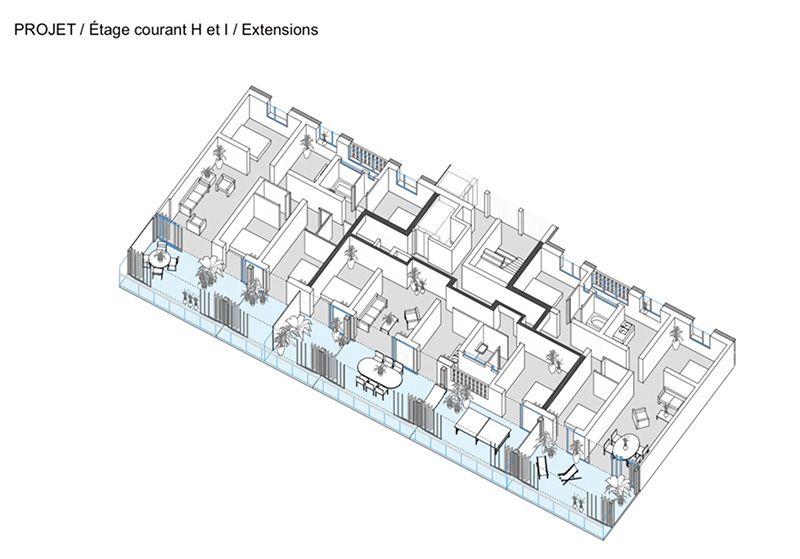

The apartments’ original unextended layout. Image © and courtesy Lacaton & Vassal/Druot/Hutin

Extended layout, with the winter garden/balcony extensions in blue. Image © and courtesy Lacaton & Vassal/Druot/Hutin

Materials and process for the winter garden extension. Image © and courtesy Lacaton & Vassal/Druot/Hutin

1 of 5

The designer’s powers of persuasion lie in making change manifest in tangible forms. Take the built environment, which accounts for 38 per cent of all carbon emissions when you factor in construction and energy use. We know that the most sustainable building is the one that already exists, and yet developers are still incentivised to demolish and build anew. The architects Lacaton and Vassal in Paris view demolition not just as waste but as a form of violence against the environment. In their transformation of social housing blocks that were once slated for demolition, they have demonstrated numerous times that such buildings can be adapted in ways that don’t just improve the architecture but also the residents’ quality of life. This is a powerful act of persuasion because it gives other municipalities the precedent they need when they are under pressure to demolish a run-down tower block.

These acts of persuasion are happening across every design discipline. Architects building taller structures with cross-laminated timber show that it’s possible to move away from carbon-heavy and hugely polluting construction mainstays such as steel and concrete. In consumer electronics, companies such as Fairphone and Framework design smartphones and laptops with modular parts, so that everything from batteries and cameras to motherboards can be replaced as they decline or evolve. While Apple and Microsoft have long used proprietary screws, glues and all manner of other strategies to prevent repair (though they’ve recently amended their policies somewhat), Fairphone and Framework are setting an ethical standard that one hopes consumers will find persuasive. In fashion, which is believed to be the second or third most polluting industry in the world, designers such as Stella McCartney, Bethany Williams and Phoebe English are demonstrating that it is possible to create desirable clothes out of recycled materials, dead stock and waste textiles. Granted, all of the above are still outliers – minnows in the mainstream – but their power lies in helping us see what a great abstraction such as ‘decarbonisation’ can look like at the everyday level.

As the public becomes more aware and more discerning, manufacturers will feel greater pressure to change – and more fundamentally than today’s epidemic of greenwashing suggests. But if the principles outlined above were widespread, it would challenge the industrial paradigm of the past 100 years. What does a society look like in which fridges last 50 years, not five? Where individual ownership of goods is replaced by communal sharing? Where distributed manufacturing is the norm, such that distant factories and global supply chains give way to more local, bioregional and artisanal production, close to the point of purchase? What are the implications of a world in which some products last forever and others, made of organic materials, decompose in days?

Our aesthetic sensibilities might have to adapt. After nearly a century of appreciating the hard-smooth-shiny perfection of plastics, we might need to embrace irregularity, imperfection, decay and decomposition. Many of these ideas and the products that could spring from them are nascent or niche. Critics will say ‘How do you scale that up?’ – to which we could retort that this impulse towards expansion is part of the problem. In the end, perhaps bigness is best replaced by myriad small-scale solutions.

There is hope, of sorts, in mushrooms. Mycelium has become the experimental material du jour, used in everything from bricks to handbags, but that is not the hope that I was referring to. Rather, it’s the fungus as a metaphor – an organism that can not only survive but even thrive in damaged landscapes, and help to restore them. The American anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing has written compellingly about the ability of the matsutake mushroom to revive pine forests that have been ravaged by fire. ‘Matsutake’s willingness to emerge in blasted landscapes,’ she writes in The Mushroom at the End of the World (2015), ‘allows us to explore the ruin that has become our collective home.’

Mycorrhizal fungi create symbiotic networks with tree roots, nourishing them and enabling life after ecological catastrophe. This is a powerful demonstration of what Tsing calls ‘entangled ways of life’, and it is precisely that entanglement that designers are beginning to learn – the way in which every object is connected to the world, through myriad social and ecological processes, from raw material to waste material. And just as the 20th century was a summer of plenty, when we could consume and discard with abandon, so the 21st century will be defined by an autumnal scarcity, in which we have to be more resourceful and sparing – keeping our eyes trained on the forest floor.

This essay appears in conjunction with the exhibition ‘Waste Age: What Can Design Do?’, running at the Design Museum, London until 20 February 2022.