U.S. is open as Canada shuts down. The difference? Their health care systems

, Bloomberg News

As omicron sweeps through North America, the U.S. and Canadian responses couldn’t be more different. U.S. states are largely open for business, while Canada’s biggest provinces are shutting down.

The difference largely comes down to arithmetic: The U.S. health care system, which prioritizes free markets, provides more hospital beds per capita than the government-dominated Canadian system does.

“I’m not advocating for that American market-driven system,” said Bob Bell, a physician who ran Ontario’s health bureaucracy from 2014 to 2018 and oversaw Toronto’s University Health Network before that. “But I am saying that in Canada, we have restricted hospital capacity excessively.”

The consequences of that are being felt throughout the economy. In Ontario, restaurants, concert halls and gyms are closed while Quebec has a 10 p.m. curfew and banned in-person church services. British Columbia has suspended indoor weddings and funeral receptions.

The limits on hospital capacity include intensive care units. The U.S. has one staffed ICU bed per 4,100 people, based on data from thousands of hospitals reporting to the U.S. Health and Human Services Department. Ontario has one ICU bed for about every 6,000 residents, based on provincial government figures and the latest population estimates.

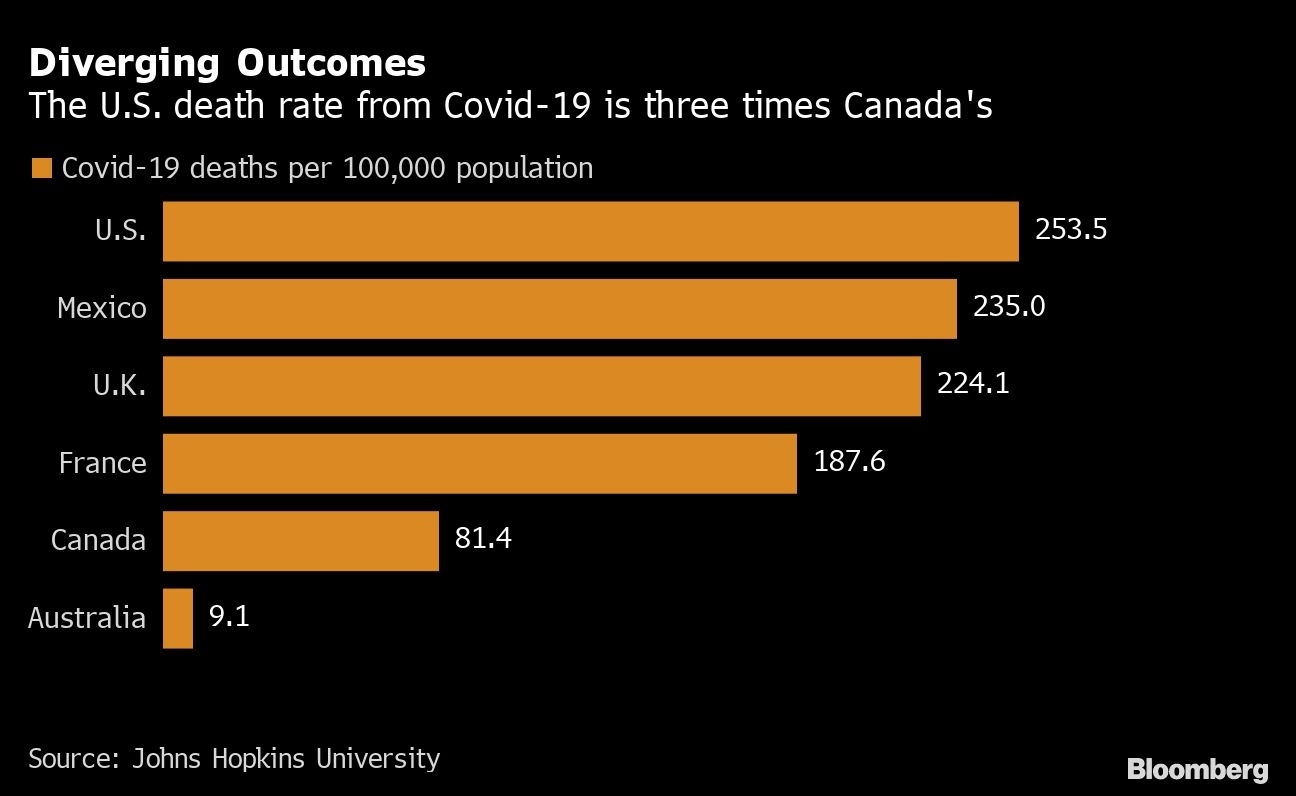

Of course, hospital capacity is only one way to measure the success of a health system. Overall, Canadians have better access to health care, live longer than Americans and rarely go bankrupt because of medical bills. Canada’s mortality rate from COVID-19 is a third of the U.S. rate, a reflection of Canada’s more widespread use of health restrictions and its collectivist approach to health care.

Still, the pandemic has exposed one trade-off that Canada makes with its universal system: Its hospitals are less capable of handling a surge of patients.

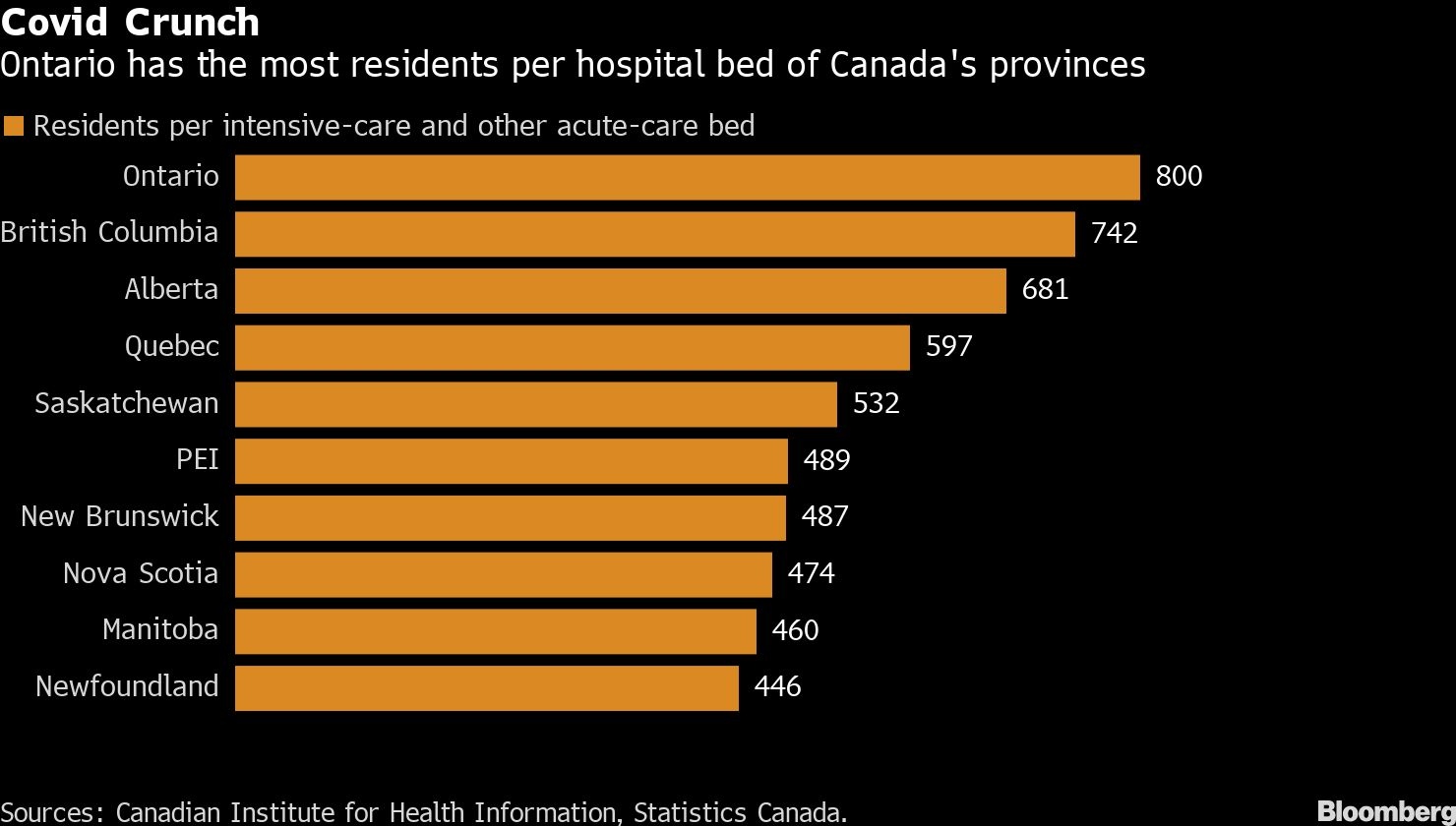

The situation is especially stark in Ontario. Nationally, Canada has less hospital capacity than the U.S. has, as a proportion of the population. But even among Canadian provinces, Ontario fares the worst. It had one intensive-care or acute-care bed for every 800 residents as of April 2019, the latest period for which data is available, according to the Canadian Institute for Health Information. During the same period, the average ratio in the rest of Canada was about one bed for every 570 residents.

That leaves the province’s health care system in a precarious position whenever a new wave of COVID-19 arrives.

“The math isn’t on our side,” Ontario Premier Doug Ford said Monday as he announced new school and business closures this week to alleviate pressure on the province’s hospitals. The province has nearly 2,300 people hospitalized with COVID-19.

NO SURGE CAPACITY

On Wednesday, after Brampton Civic Hospital in the Toronto suburbs declared an emergency because of a shortage of beds and workers, Brampton’s mayor, Patrick Brown, tweeted: “We need a national conversation on inadequate health care capacity and staffing.”

The biggest bottleneck in the system is the staffing required by acute care, particularly in the emergency departments and intensive care units, Bell said. The personnel crunch becomes extreme during COVID waves when large numbers of staff are forced to isolate at home because of infection or exposure.

“We haven’t done an adequate job of developing capacity that will serve the needs of Ontarians,” Bell said. “There’s just no surge capacity available.”

Stephen Archer, head of the medicine department at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, about three hours east of Toronto, spent two decades working in hospitals in Minneapolis and Chicago. He said he believes strongly that the Canadian system is better and provides more equitable care.

Still, he called it “embarrassing” to see Toronto’s hospitals having to transfer virus patients to smaller hospitals around the province, as happened last year. The Kingston Health Sciences Center, where he works, took in more than 100 COVID patients from Toronto earlier in the pandemic, which was no surprise, Archer said, because Ontario’s hospitals get overwhelmed even by a busy flu season.

“I think a very fair criticism of the Canadian system and the Ontario system is we try to run our hospitals too close to capacity,” he said. “We couldn’t handle mild seasonal diseases like influenza, and therefore we were poorly positioned to handle COVID-19.”

Beyond hospital capacity, Archer and Bell cited other reasons for the disparity in the way that the U.S. and Canada respond to new outbreaks. Canadians put more trust in their government to act for the larger collective good, and they won’t tolerate the level of death and severe disease that America has endured from COVID, they said.

David Naylor, a physician and former University of Toronto president who led a federal review into Canada’s response to the 2003 SARS epidemic, said hospital capacity probably plays a bigger role in Canadian decision-making than in the U.S. because Canada’s universal system means “the welfare of the entire population is affected if health care capacity is destabilized.”

But he also argued that focusing only on hospital capacity could be misleading. “Both Canada and the U.S. have lower capacity than many European countries,” he wrote by email.

The major difference between the two countries’ responses to COVID outbreaks is cultural, Naylor argues. In Canada, more than the U.S., policy is guided by a “collectivist ethos” that tolerates prolonged shutdowns and other public health restrictions to keep hospitals from collapsing.

“America’s outcomes are almost inexplicable given the scientific and medical firepower of the USA,” Naylor said. “With regret, I’d have to say that America’s radical under-performance in protecting its citizens from viral disease and death is a symptom of a deeper-seated political malaise in their federation.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/HZJJCSKF2ZMHFK423ZQIHSXPYQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/JVW34QMVMVP2LPGFRBNXQU56AY.jpg)