Take This Job and Shove It!: The Growing Revolt Against Work

“Experience demonstrates that there may be a slavery of wages only a little less galling and crushing in its effects than chattel slavery, and that this slavery of wages must go down with the other”

-Frederick Douglass

“A worker is a part time slave”

-Bob Black

There is something very strange going on with the US economy, dearest motherfuckers, and you don’t have to look at the Dow Jones to see it. All you have to do is take a stroll down main street. Everywhere you look on every storefront and shop window from your local Wendy’s to the bank, there are signs screaming ‘Help Wanted!’, ‘Parttime and Fulltime Positions!’, ‘Jobs Available!’, ‘Seriously Dude, Fucking Work Here!’ Businesses of nearly every variety are practically begging for employees but there are no employees to be found. The bean counters in the Federal Government have taken notice too. The latest job reports from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics reveal the sheer Grand Canyon magnitude of this thing in flashing red numbers. Over 20 million Americans have quit their jobs in the second half of 2021, a record 4.5 million in November alone, that’s fucking holiday season! This is literally unlike anything we’ve ever seen before and there are no signs of it slowing down in the foreseeable future. Some clever motherfucker has coined this dumbfounding phenomenon the Great Resignation. We have an economy drowning in job offerings, but no one wants to work, and all the experts seem beside themselves explaining why.

Far be it for me to call myself an expert. I don’t have any Ivy League degrees hanging over the credenza or a position at some smarmy Randian think tank, but I am one of these unemployed people these experts seem to be so mystified by and I do have a theory that might shine some light on their conundrum. Are you ready? Listen very carefully so as not to miss the subtle nuances of my argument. Work fucking blows! It sucks and plebian scum like me don’t wanna live like that anymore and why the fuck would we? It’s not natural and it’s not fucking healthy, spending 80% of your life stewing in traffic jams, slaving behind deep fryers, and punching numbers into computers. We’re not descended from ants. People are monkeys. God designed us to eat, fuck, fight, shit, repeat, and we’re done with civilization’s fucking capitalist zoo.

We’ve all been duped into accepting wage slavery as the natural order of existence but even a cursory glance at history tells us that this is total bullshit. The modern concept of work as we know is only a few centuries old. It’s a byproduct of the 16th Century Protestant Reformation and it wasn’t designed for productivity; it was designed as a means of social control. Those assholes taught us that working ourselves to death would bring us closer to God so they could keep us from jacking off. When the bank took the church’s place during the Industrial Revolution, the bourgeoisie simply replaced God with a dollar bill and used the death cult of the Protestant Work Ethic to squeeze every last drop of man-hours out of the proletariat like a dirty dishrag. They work us so goddamn hard that we don’t even have enough free time to revolt, let alone masturbate, and that’s not just a happy coincidence.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. Human beings spent 90% of our history in hunter-gatherer societies and we were a hell of a lot happier as savages. We spent no more than 3 to 5 hours a day hunting, foraging, fishing, and preparing food and spent the rest of our time fucking off, smoking dope, and inventing wheels. The great anthropologist Marshall Sahlins called it the original affluent society and it existed for thousands of years without managers, bathroom breaks, Muzak, and office Christmas parties. In the centuries since most of mankind abandoned to nature, we’ve developed such smashing advances in modern technology as prisons, genocide, factories, compulsory schooling, nuclear bombs, shrinking icecaps, and islands of garbage the size of continents. This lifestyle choice known as work is an anomaly, an offramp to human devolution like monotheism, Celine Dion, and the gender binary. If the gods wanted us to live this way, we wouldn’t be choking to death on our own exhaust fumes. Climate change is a warning and so was Covid.

Whether it was the fruit of gain of function or just too many condos too close to the bat caves, the Pandemic served as a violent alarm clock to many hardworking Americans. In a matter of months, 25 million people either lost their jobs or had their hours drastically cut. People also lost their homes, their cars, and their healthcare insurance. In the blink of an eye, all the lies of our statist consumer culture had been stripped naked and people didn’t like what they saw. It turns out that our advanced western society offered no real security when the shit got real, and Americans started to seriously rethink this whole work thing.

The Antiwork Movement isn’t exactly new. It’s as old as Proudhon and Marx. Anarchists and socialists like William Morris, Paul Lafargue, Ivan Illich, Bob Black, and David Graeber have been telling any working stiff who’ll listen for generations that we’ve been hoodwinked, but it took the Pandemic to make a modest movement into a monster. Since the lockdowns, a once humble antiwork page on Reddit has rapidly ballooned into one of the site’s fastest-growing subreddits with over 1.4 million members and growing. They call themselves Idlers and they’ve made their voices heard well beyond the echo chambers of social media by organizing Black Friday boycotts and by shutting down Kellog’s job portal with a deluge of spam in solidarity with striking factory workers.

It’s a big fucking movement and like any big fucking movement there is a diverse array of opinions and not everyone is on the same page. Speaking as a post-left panarchist, I’m a strong believer in creating an endless variety of stateless options provided that they’re all 100% voluntary. I see no reason why primitivists and hunter-gatherers can’t coexist with small autonomous syndicalist factories and family farms as long as we all agree to hang the boss man by his tie. Hierarchy needs to be recognized for the modern social pollution that it is but there are all kinds of funky dance moves that can be used to stomp out that fire before it engulfs us all. I’m inspired by these cyber idlers getting together and sharing information on everything from how to get paid while slacking off to eking out a sustainable living-making soap. I believe that this is a movement that plausibly has more potential than Occupy because it calls on its members to take back their own God-given autonomy and totally rethink the way we organize society. But for disabled people like me this has never really been a choice to begin with.

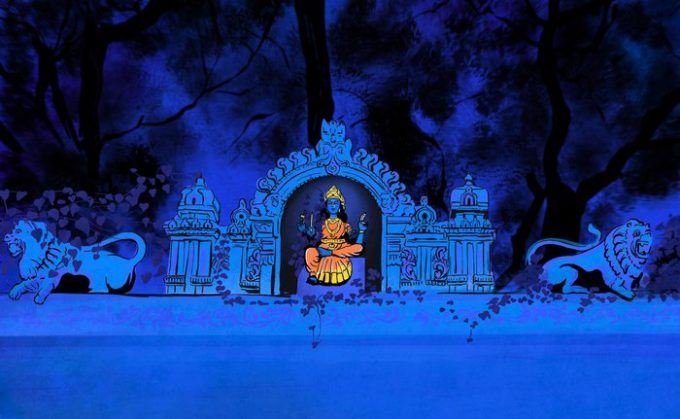

I don’t work, dearest motherfuckers, because I can’t work. I was born with more mental illnesses than I can count, and I’ve only collected more over the years. They have all kinds of fancy intellectual labels, dysthymia, agoraphobia, social anxiety disorder, gender dysphoria, OCD, PTSD, ADD, but they all essentially add up to one thing. Like many other Americans, I am simply pathologically unemployable. I couldn’t make it in the straight world if I wanted too and Kali knows I’ve tried. Just the idea of a 9-to-5 existence, with its fast-paced monotony, erratic hours, swollen crowds of irate customers, and role-crazy teenage despots, gives me a nervous breakdown. It has forced me to do the unthinkable as an anarchist and go on government disability just to make ends meet, and I used to kick my own ass for being this way but the more I think about it the more I’ve come to realize that I’m not the one with the fucking problem.

The definition of mental illness and disability is essentially suffering from an inability to conform to the confines of mainstream society but considering how corrupt and downright evil this pandemic has proven mainstream society to be, I believe people like me aren’t so much crippled as we are allergic to the social toxins of a malignant civilization and just like the ranks of the Antiwork Movement, our numbers are growing. I refuse to accept that it’s merely a coincidence that more Americans than ever are emotionally unstable and neurodivergent in times like these. We are the human equivalent of climate change. We have evolved into something incompatible with the evils of perpetual growth.

I’m done beating myself up for being a freak. Just like my decidedly unconventional gender identity, I’m proud of being biologically driven to break with modern society. But I’m also done with welfare. It’s a form of social control just like employment and I’m committed to escaping its cage as soon as I can pick the lock. This is why I oppose Universal Basic Income, an idea very popular with many in the antiwork community. Programs like these do nothing to upend the power imbalance of the workplace. They merely replace the boss man with a bureaucrat and offer you a steady trickle of income as long as you obey the state that doles it out.

They’re essentially paying us not to revolt while they rape the planet blind with their toxic sludge-belching genocidal war machine. I refuse to be complicit. The Antiwork Movement has inspired me to plot my escape. Instead of working or preparing myself mentally to assimilate into the workforce, I’m devoting my time to strengthening my people in my local Queer and disabled communities. I’m preparing to learn how to shoot, make scented candles from scratch, freelance as a dominatrix, and get certified to give blood tests at local shelters. All while I finish writing the great Queer American novel and every day, I come a little closer to chewing through the leash.

But this thing is bigger than me. It’s bigger than any of us individually. The Antiwork Movement has the awesome capability of being nothing short of revolutionary. If we can get enough people to drop out of mainstream society and go off the economic grid, we can slay this beast called empire. By building a new economy based totally on freelance subsistence labor and voluntary grey market exchanges we can simultaneously starve both the Federal Government of our tax revenue and their friends in the Fortune 500 of our wage-slave labor, killing the incestuous tag-team of big business and big government with one stone without so much as firing a single bullet. We can destroy the old system by merely rendering it obsolete with a new one. And it all starts with a pink slip that reads ‘take this job and shove it.’