In the 49 years since the Supreme Court ruled in Roe v. Wade, lawmakers have attempted to both shore up abortion rights and to overturn the decision — all while abortion transformed national politics.

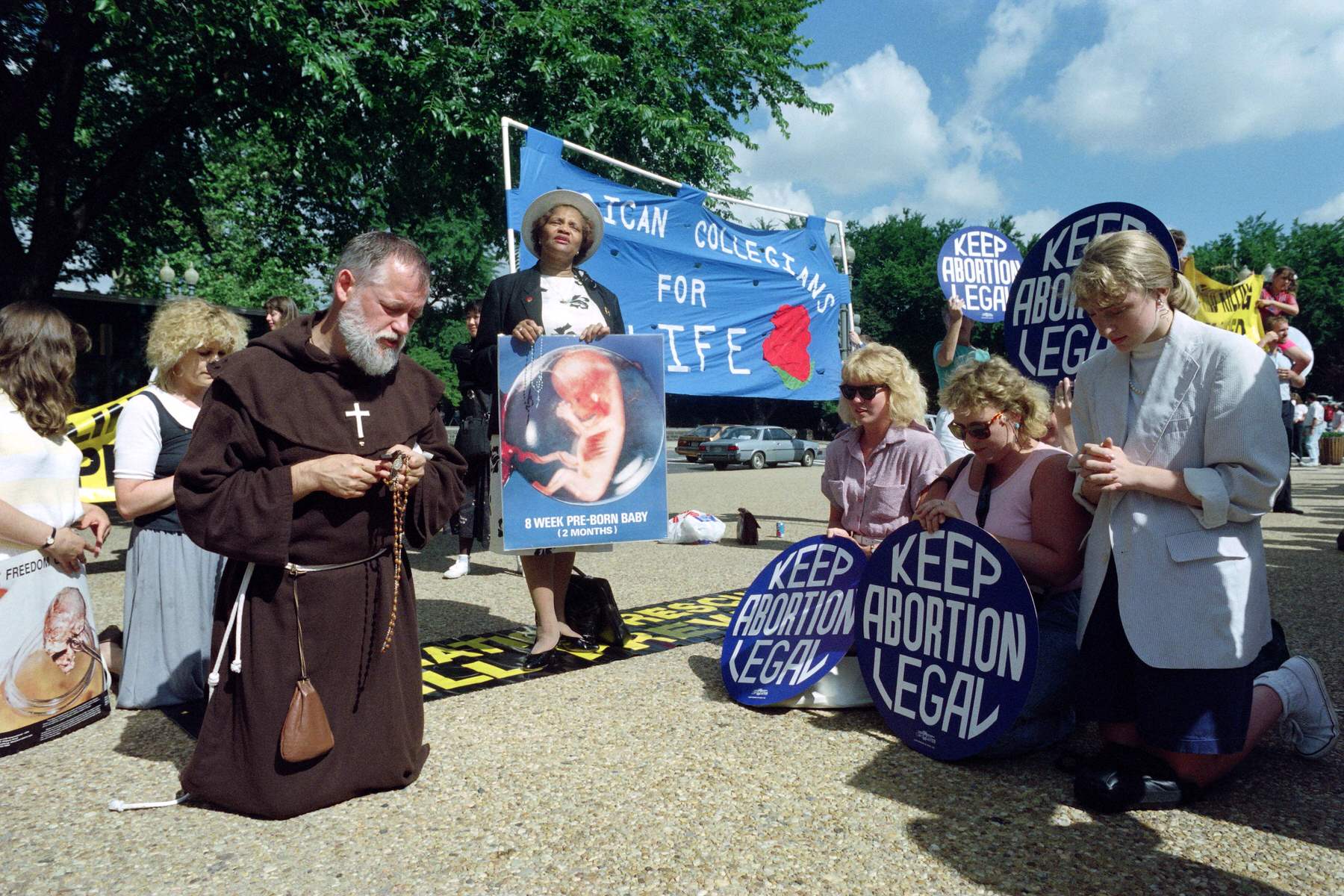

Demonstrators at the March for Women's Lives at the Capitol on April 9, 1989.

Amanda Becker

Washington Correspondent

Published January 26, 2022

When the U.S. Supreme Court in September left Texas’ restrictive six-week abortion ban in place, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi quickly responded that the conservative majority’s “dark-of-night decision” was “flagrantly unconstitutional” and would be met with swift congressional action.

It was. Three weeks later, the House passed by a 218-to-211 vote the Women’s Health Protection Act, which would prohibit states from passing most abortion restrictions prior to fetal viability. It was opposed by all House Republicans, along with Rep. Henry Cuellar of Texas, the chamber’s last anti-abortion Democrat.

The Senate has yet to act. Even if it did, the bill is unlikely to pass the evenly divided 100-seat chamber, where nearly all legislation needs 60 votes to overcome the filibuster. So even as Republican state lawmakers introduce copycat bans based on the Texas law, and the Supreme Court weighs a case that could upend abortion rights, the chance of federal legislation making it to President Joe Biden’s desk by November, when Democrats could lose control of the House, the Senate or both, is basically nonexistent.

Forty-nine years have passed since the Supreme Court’s 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade established the constitutional right to an abortion before fetal viability. There have been congressional attempts to pass a constitutional amendment overturning Roe, as well as efforts to codify the decision. All have failed. Along the way, abortion has transformed national politics and created a gulf between voters and party leaders to the extent that by 2019, as many as 3 in 10 Democrats and Republicans did not agree with their party on abortion, according to the Pew Research Center.

Calls from Democrats to “codify Roe” have intensified in recent months, with Roe’s 49th (and potentially last) anniversary last week, several intermediary decisions on the Texas law, and a separate case — Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization — before the Supreme Court concerning a 15-week abortion ban in Mississippi. Last month during oral arguments in that case, a majority of justices indicated that they are willing, at minimum, to weaken the viability standard set by Roe at approximately 24 weeks pregnancy.

A Supreme Court ruling in Dobbs is expected by summer, and it has the potential to cap a decades-long effort by conservative abortion opponents to gut the Roe ruling and leave the issue up to the states.

How the two parties arrived at this pivotal moment for abortion access involves the emergence of a new wedge issue, a realignment of the political parties, and decisions they made along the way about when and how to push for abortion regulations and to what extent.

And it all happened within the past 50 years.

Cecile Richards, president of the reproductive health organization Planned Parenthood and its affiliated political arm from 2006 to 2018, bristles when she hears the word “controversial” used to describe abortion. Public opinion has shown a majority support for abortion access that has remained remarkably consistent, she said.

A June 2021 survey of U.S. attitudes about abortion rights and Roe from public opinion polling firm Gallup, for example, showed that 58 percent of Americans opposed overturning the 1973 ruling and 32 percent favored it — mirroring public opinion in 1989.

“I think some people have a hard time wrapping their head around two different ideas: One is that people have their own personal feelings about abortion, their own experience with it, what they feel like they would do, what they would want their daughter to do,” Richards told The 19th. The other is that they “absolutely do not want the government to make these decisions.”

More from The 19th

Texas’ six-week abortion ban will stay in effect indefinitely after Supreme Court decision to allow legal delays

Abortion rights groups tie their fight to voting rights

Abortion rights advocates want to hear more from Joe Biden

“The only thing that’s changed is the politics of the Republican Party and frankly, the Democratic Party,” she added.

In 1975, when abortion was a newly established constitutional right, 19 percent of Democrats told Gallup that abortion should be legal in “all or most cases,” 51 percent said it should be legal in certain cases, and 26 percent said it should be illegal in all cases. Among Republicans, the numbers were strikingly similar: 18 percent said abortion should be legal in “all or most cases,” 55 percent said it should be in some and 25 percent said it should be illegal in all.

The same poll taken in 2021 showed more Democratic voters supporting abortion in “all or most cases” and more Republicans supporting it in none, with sizeable majorities in both parties — 91 percent of Democrats; 69 percent of Republicans — continuing to support abortion access in at least some cases.

But the parties in Congress are less nuanced. In the House, Texas’ Cuellar is considered the only reliably anti-abortion Democrat and, as of 2019, there are no Republicans who support abortion rights. In the Senate, Democrats Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Bob Casey of Pennsylvania both self identify as “pro-life,” though they have at times supported forms of abortion access, and Republican Sens. Lisa Murkowski of Alaska and Susan Collins of Maine have both embraced some abortion rights.

As political scientists Scott Ainsworth and Thad Hall write in the 2010 book “Abortion Politics in Congress”: When it comes to abortion, “the increasingly partisan nature of abortion politics represents a case of issue evolution driven by party elites and filtering down to the masses.”

Alisa Von Hagel is a political science professor and coordinator of the gender studies program at the University of Wisconsin–Superior who tracks the emergence of abortion policy, particularly at the state level. She said one key to understanding abortion politics in 2021 is knowing that just several decades ago it was not considered a political issue at all.

Von Hagel recalled a student who told her about a conversation with their grandmother and several others from that generation about studying the politics of reproductive rights. “These older ladies were just like: Why in the world is this a political issue? We never talked about it like that in the past,” Von Hagel remembers the student relaying. “I can still picture her face, thinking: ‘How is this possible?’”

“It was a very, very purposeful realignment that happened,” Von Hagel added.

Heading into the 1970s, political affiliation was not an accurate predictor for whether an individual supported abortion rights — for voters or elected officials. But over the next 20 years, a political party realignment around abortion would begin to take shape.

The term “pro-life” was not even in the political lexicon in 1972, when Republican Richard Nixon adopted anti-abortion positions during his presidential reelection campaign in a successful bid to win over Catholic voters, who had traditionally backed Democratic presidents, including the two before Nixon.

The Supreme Court’s 1973 ruling in Roe v. Wade energized the anti-abortion coalition of evangelical as well as Catholic voters that began to emerge during Nixon’s presidency and still exists in politics today. Privately, Nixon told top aides that while he feared the ruling could encourage sexual promiscuity, he believed abortions should be available in certain circumstances, such as for pregnancies resoluting from incest or interracial relationships.

Mary Ziegler, a law professor at Florida State University who studies abortion, believes that the Senate probably had a bipartisan majority that supported abortion rights when Roe was decided, but advocates did not feel a pressing need to pass legislation.

“It seemed to be kind of like overkill, because at the time, the abortion rights movement trusted the courts to protect abortion rights for some time,” Ziegler told The 19th.

During the 1976 presidential campaign, both Republican Gerald Ford and Democrat Jimmy Carter opposed abortion in some cases. That year Congress for the first time approved the Hyde Amendment, which bars using federal dollars for most abortions, including in the government’s Medicaid health insurance program.

More Democrats than Republicans voted for for it, handing abortion rights opponents their first post-Roe victory. But some of those Democrats did so because it seemed like abortion rights were settled law and the Supreme Court would step in when it was challenged, according to Ziegler.

“There were some Democrats and progressives who voted for the Hyde Amendment in part because they thought the Supreme Court would invalidate it — it was part of an appropriations bill, so if you liked other stuff in the appropriations bill, that was fine, because the Supreme Court would take care of it,” Ziegler said.

It didn’t. The court upheld the constitutionality of the Hyde Amendment in 1980.

It was around this time that “abortion started to become linked to ideology and party in ways that had not occurred before,” according to Ainsworth and Hall. Republican Ronald Reagan — who had relaxed abortion restrictions as California’s governor — called for the appointment of anti-abortion judges during his 1980 White House campaign. By the late 1980s, he had nominated more federal judges than any president before or since, and abortion rights groups began to realize “we can’t really rely on the courts anymore, we need to find a way through the political process to protect access to abortion,” Ziegler said.

When Democrat Bill Clinton campaigned for the White House in 1992, he did so with the message that abortion should be “safe, legal and rare.” At the time, that was the most forceful support for abortion rights from a post-Roe president, but it has since become outmoded in Democratic politics. When Rep. Tulsi Gabbard of Hawaii repeated it during the 2020 presidential primary, abortion rights advocates said she was out of step with a movement that believed “rare” was a concession to their opponents.

Once president, Clinton marked the 20th anniversary of the Roe decision by reversing abortion restrictions put in place by the Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations. But legislation proved harder. Though Clinton began his presidency with Democrats in control of both the House and Senate — and with a majority that backed abortion rights, according to Ziegler — disagreements in his own party remained over how to handle the Hyde Amendment and other specifics.

In 1992, the Supreme Court had affirmed the right to an abortion in the case Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which challenged restrictive Pennsylvania laws. But the ruling also said states had some leeway to add some limits to abortion during the first trimester of pregnancy. So Democrats revived the Freedom of Choice Act — that era’s attempt to codify Roe. When it failed in 1993, Democratic leaders turned their focus to health care legislation.

“When it starts to take too long, you see the Democratic Party essentially saying: Well, we’re not going to worry about this, we’ll get to this later,” Ziegler said.

According to Michele Swers, a government professor at Georgetown University, the “most aggressive Democrats got” on abortion rights during this time period was the FACE Act, a law that protected clinic entrances. The window for any broader effort closed when Democrats lost control of both chambers of Congress in the 1994 midterm elections.

In 1994, the Republican Party ran on its newly released Contract with America. Though by that time the party’s candidates and lawmakers were increasingly aligning with the anti-abortion movement, the contract focused on “60 percent issues” that had broad support from the electorate like slashing welfare programs and a balanced budget amendment. Overturning Roe was not one of them, so it was silent on abortion. The contract fueled Republican victories in the House and Senate, putting them in control of both congressional chambers for the first time since the 1950s.

In early 1995, the Christian Coalition, a group founded in 1987 by religious conservative and former presidential candidate Pat Robertson that became emblematic of the Christian right, released its own “contract with the American family” at a news conference alongside then-House Speaker Newt Gingrich, one of the authors of the party’s 1994 platform. That “contract” did not propose a constitutional amendment to ban abortion outright due to practical concerns, political analysts said at the time, but it did call for restrictions on late-term abortions. Even still, intraparty divides over abortion existed. Then-Sen. Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania, who was considering a Republican presidential bid based on curbing religious influence on the party, told ABC’s “Good Morning America” that he would not support it because “it opposes a woman’s right to choose.”

What followed was a period when increasingly socially conservative Republican lawmakers and abortion opponents became more tenacious in supporting incremental restrictions. Republicans attached abortion-related riders to appropriations bills and repeatedly introduced what would become known as the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act, which the Republican-controlled Congress passed twice only to be vetoed by Clinton, then eventually signed into law by Republican President George W. Bush in 2003.

It was during debate over the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act, which banned abortions by “dilation and extraction” in the second trimester of pregnancy, that public opinion about an absolute right to legal abortion began to shift, according to tracking polls and Ziegler’s research — and reproductive rights advocates worried they were losing the messaging battle. Even the name of the law, which adopted a term not used in medicine to describe late-term abortions, was seen as a victory for abortion opponents. In the House, the final version of the legislation was backed by 218 Republicans and 63 Democrats; in the Senate, 47 Republicans and 17 Democrats. Its constitutionality was upheld by the Supreme Court in 2007.

Richards said that when she got to Planned Parenthood in 2006, the Democratic Party was still recruiting congressional candidates who did not support abortion rights. The organization “really worked hard to establish that it was a fundamental right, and that it was something that the Democratic Party needed to lead on.”

Abortion rights advocates found an ally in then-Sen. Barack Obama, who told Planned Parenthood early in his Democratic White House bid that “the first thing I’d do as president” would be to codify Roe by signing the latest iteration of the Freedom of Choice Act. But four months into his presidency, Obama said it was “not my highest legislative priority” and suggested energy would be better spent reducing unintended pregnancies.

But Democratic differences on abortion threatened to derail Obama’s namesake health care law. With Republicans united in opposition, Democrats could not afford to lose a single senator, and Ben Nelson, an anti-abortion Democrat from Nebraska, was the final holdout. To win his support, party leaders included a version of an amendment that prohibits Affordable Care Act plans from covering abortion, which was originally offered by another anti-abortion Democratic representative, Bart Stupak of Michigan. To appease opponents, Obama also issued an executive order reiterating that federal money would not be used to pay for abortions. Meanwhile, abortion rights advocates tried to take solace in the fact ACA plans would cover contraception.

In the 2010 midterm elections, Republicans picked up more than 60 House seats to retake control of that chamber and added seven in the Senate as part of the tea party wave. Republican efforts picked up to “defund” Planned Parenthood by denying the organization state and federal money throughout the rest of Obama’s presidency, many of them spearheaded by then-Rep. Mike Pence. In 2015, Republican House Speaker John Boehner resigned in part due to repeated battles with the conservative Freedom Caucus over their desire to shut down the government over Planned Parenthood funding.

In January 2016, Planned Parenthood, under Richards’ leadership, endorsed Democrat Hillary Clinton’s White House bid. It was the first time the organization had made an endorsement in a presidential primary, but as Richards told the New York Times: “Everything Planned Parenthood has believed in and fought for over the past 100 years is on the ballot.” When Clinton accepted the endorsement and announced that she supported repealing the Hyde Amendment, the Guardian called it “truly surprising” and Salon said it was a “game changer.” Hyde Amendment repeal ended up in the Democratic Party’s official policy platform — a move polling showed was popular with the party’s base but less so with the broader electorate.

Clinton went on to lose the November 2016 election to Republican Donald Trump, who said he was running to be a “pro-life president” and had taken a number of anti-abortion stances during his campaign. He was the first sitting president to attend the annual March for Life rally and appointed three Supreme Court justices — Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett — who cemented the court’s conservative anti-abortion majority.

By the time the 2020 Democratic presidential primary got underway, the sizable field of contenders all supported some version of Roe codification and the repeal of the Hyde Amendment, citing the Trump administration’s attempts to curb abortion access and restrictive laws recently enacted in Georgia and Alabama. To run for president as a Democrat in 2020 meant unequivocally supporting abortion rights — and for Joe Biden, an observant Catholic, it necessitated an evolution.

After Biden joined the Senate in 1973, he voted for a failed constitutional amendment that would have allowed states to overturn the court’s Roe ruling. In a Washingtonian magazine interview at the time, he said of Roe: “I think it went too far. I don’t think that a woman has the sole right to say what should happen to her body.” But times changed, and so did he. In a 2007 book, Biden said he had arrived at a “middle-of-the-road position on abortion.” In 2008, he described Roe as “close to a consensus that can exist in a society as heterogeneous as ours.” As Obama’s vice president, Biden said the government had no “right to tell other people that women, they can’t control their own body.”

By the 2020 presidential primary, his abortion politics matched the party’s base.

Biden went on to drop the Hyde Amendment in his first budget proposal. Early in his presidency, he also rescinded the Mexico City Policy, known as the global gag rule, which requires foreign organizations to certify they will not promote abortion as a condition for receiving U.S. aid for reproductive health care. In October, his administration reversed a Trump-era regulation that barred health care providers receiving Title X family planning funds from mentioning abortion care to patients as an option.

Biden has emphasized codifying Roe as a proxy for his larger abortion messaging and has said he would sign the Women’s Health Protection Act if it were to make it to his desk. But, with anti-abortion conservatives anticipating judicial victory, it is unclear what, if anything Biden’s administration — or Democrats in Congress — can deliver legislatively.

Since Democrats lack a legislative path to head off the Dobbs decision, they have turned to making the case that voters should reinforce their congressional majorities in the 2022 midterms, believing the party’s support for abortion access will benefit their candidates up and down the ballot.

“We are in a total stalemate in Congress and it would take extraordinary leadership by this president and frankly, by the Democrats in the United States Senate, to do anything legislatively to codify Roe,” Richards said.

“I don’t think most people, unless they live in the state of Texas, know what is potentially coming,” she added.