By Laura Oliver |

A solar farm in Cauchari, Jujuy province. Image: Screenshot (La Nación)

This article was originally published by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism and is republished here with permission. It is part of an ongoing series of cross-posts GIJN is running on AI and investigative journalism.

Media companies are looking at artificial intelligence (AI) in 2022, according to Nic Newman’s Trends and Predictions 2022 Report, based on a survey of hundreds of media leaders around the world. For newsrooms looking to deepen their understanding of how AI could be used for newsgathering, storytelling, and business purposes, La Nación is blazing a trail. The 150-year-old Argentinian newspaper has produced a diverse range of stories assisted by AI technologies and has created an AI lab.La Nación needed an infrastructure and skills that it didn’t yet have in its newsroom to produce this reporting.

La Nación’s experiments with AI began with an investigation into private renewable energy in Argentina. In 2016, Mauricio Macri, the Argentinian President at the time, launched a program to open up the country’s clean energy resources to private and international investment. Inspired by an initiative mapping every solar panel in the US she had encountered as a JSK Knight Journalism Fellow at Stanford, Florencia Coelho, new media researcher at La Nación, pitched a project to map the government program’s progress four years after it was launched.

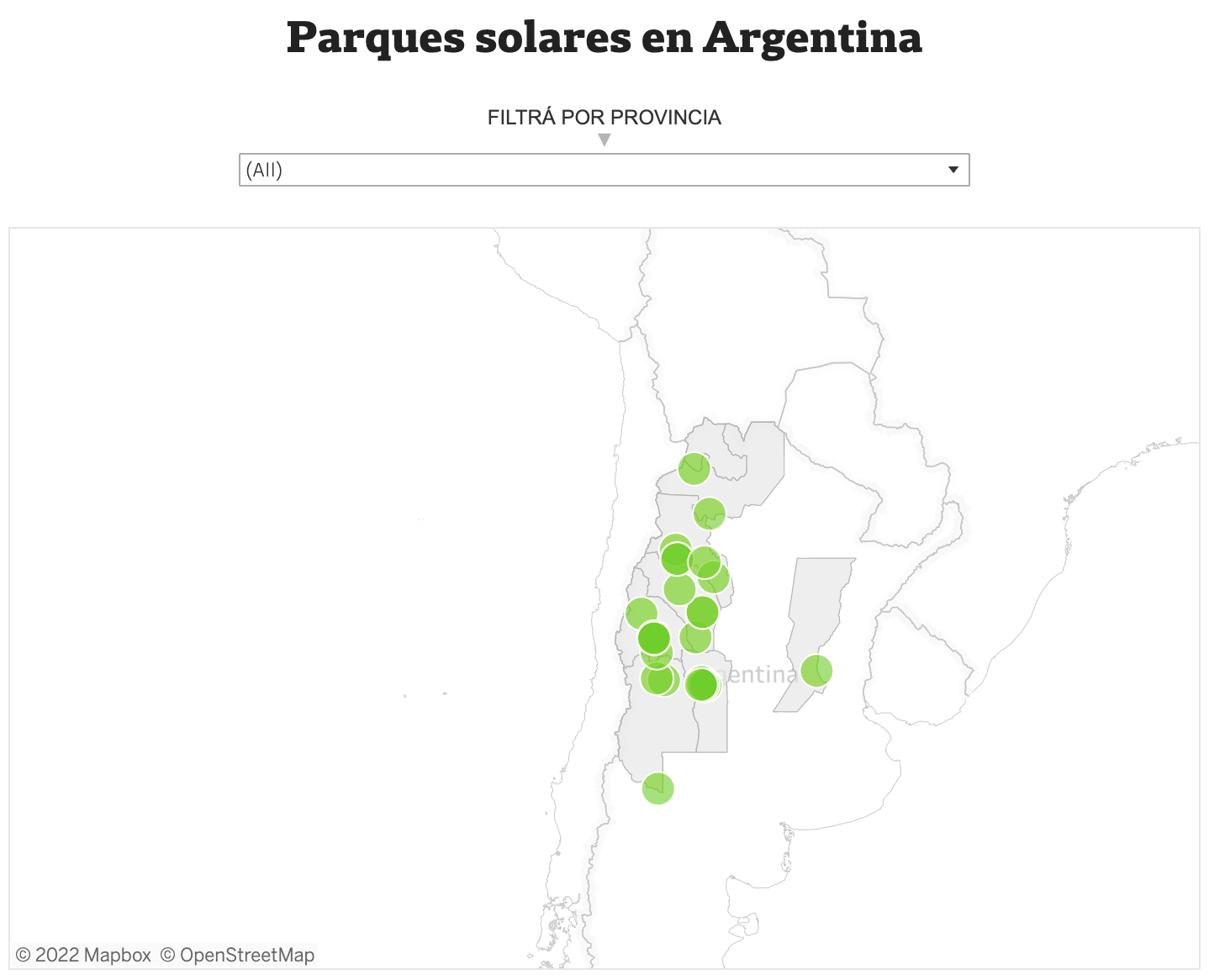

La Nación data team started the project in collaboration with Mathias Felipe, a visiting fellow from the University of Navarra in Spain. The team used machine learning and computer vision, and worked with a third-party lab specializing in geospatial analysis and AI. La Nación’s algorithm was trained to identify the shape of solar farms in Argentina. Computer vision is a process that trains computers to analyze and understand visuals. So 10,999 images were used to train the algorithm before a total of 7 million images were processed and 2,780,400 square kilometers (1,074,000 square miles) of land analyzed. The data suggested the government program had not met its

targets.

A map from La Nación’s investigation into the Argentinian government’s pledge to build solar farms. Image: Screenshot (La Nación).

The project threw up some challenges. Accessing satellite imagery is costly. Solar farms look like agricultural farms depending on what image-recognition system you use. They didn’t have enough images of solar farms in Argentina in 2019 to train the model so images from Chile had to be sourced. “We couldn’t map every solar panel in Argentina because it needed very high-definition imaging, so we focused on solar farms because machine learning looks at shapes and this was an easier pattern for them to identify,” Coelho says.

Ultimately, La Nación needed an infrastructure and skills that it didn’t yet have in its newsroom to produce this reporting. “We didn’t have all the hardware and computing power needed for this project, so that’s why we collaborated. It was data for good,” says Coelho.

Analyzing Trap Song Lyrics

From this early example, the La Nación data team learned the benefits of collaboration. They also learned that until their own tech-savvy in terms of AI grew they they might not be able to ask the right questions, such as testing how accurate a model is. Setting up an AI lab involving journalists, data analysts, and developers to work on AI projects within La Nación’s newsroom has helped expedite this learning process. None of the seven staff members work in the lab full-time, though, as they have other commitments in the newsroom.

The lab’s first project was an analysis of the lyrics of trap music that took seven months to complete. Gabriela Bouret and Delfina Arambillet were the leaders of the project, in which Coelho didn’t participate. The team used machine learning, natural language processing, Spotify’s API, and lyrics from genius.com to process 692 songs and dig into the topics, trends, and messages of this increasingly popular music genre in Argentina. The AI that journalists used had to deal with some linguistic problems, including invented words used in trap songs. An interactive feature, including an extensive trap dictionary, an “egometer” measuring how many times an artist mentions him or herself, and other analysis of hallmarks of the genre allowed readers to explore the results.

The project threw up some challenges. Accessing satellite imagery is costly. Solar farms look like agricultural farms depending on what image-recognition system you use. They didn’t have enough images of solar farms in Argentina in 2019 to train the model so images from Chile had to be sourced. “We couldn’t map every solar panel in Argentina because it needed very high-definition imaging, so we focused on solar farms because machine learning looks at shapes and this was an easier pattern for them to identify,” Coelho says.

Ultimately, La Nación needed an infrastructure and skills that it didn’t yet have in its newsroom to produce this reporting. “We didn’t have all the hardware and computing power needed for this project, so that’s why we collaborated. It was data for good,” says Coelho.

Analyzing Trap Song Lyrics

From this early example, the La Nación data team learned the benefits of collaboration. They also learned that until their own tech-savvy in terms of AI grew they they might not be able to ask the right questions, such as testing how accurate a model is. Setting up an AI lab involving journalists, data analysts, and developers to work on AI projects within La Nación’s newsroom has helped expedite this learning process. None of the seven staff members work in the lab full-time, though, as they have other commitments in the newsroom.

The lab’s first project was an analysis of the lyrics of trap music that took seven months to complete. Gabriela Bouret and Delfina Arambillet were the leaders of the project, in which Coelho didn’t participate. The team used machine learning, natural language processing, Spotify’s API, and lyrics from genius.com to process 692 songs and dig into the topics, trends, and messages of this increasingly popular music genre in Argentina. The AI that journalists used had to deal with some linguistic problems, including invented words used in trap songs. An interactive feature, including an extensive trap dictionary, an “egometer” measuring how many times an artist mentions him or herself, and other analysis of hallmarks of the genre allowed readers to explore the results.

A gif showing La Nacíon’s trap music project. Courtesy of La Nación

Much of what they learned, Coelho says, can be applied to other types of music or even to different texts. “Today the topic was trap, but tomorrow we may use this for political discourse or for a different topic,” says data analyst Gabriela Bouret.

Bringing new technologies, reporting processes, and topics into play has pushed the newsroom too. “It was such a different thing to publish in La Nación,” Bouret notes. “It’s a very traditional newspaper and trap is especially for very young people. It’s totally different from what our audience expects from us and gets us out of the box.”

La Nación’s experiments are also exposing that AI has been built or trained for the English language and for audiences in the Global North. “Every [natural language processing] model has been prepared for the English language,” says Bouret. “It was very difficult for us to find the libraries and the processes to help us deal with the problem of the Spanish language [for the trap project].”

AI for Electoral Coverage

In 2021, the newsroom again used computer vision to detect errors in the telegrams returned from polling stations during parliamentary elections in Argentina.

Working with a third-party company to build and train an algorithm to identify inconsistencies in the telegrams, which record details including the number of votes won by each party and how many election monitors were present, human volunteers were then asked to sift through flagged records. La Nación used its existing VozData platform, where readers have collaborated on data investigations and worked with transparency initiatives and universities. Human helpers refined the algorithm: it had to be adjusted to deal with telegrams that were wonky or that had been uploaded upside-down. The results suggested that 95% of telegrams returned were filled out correctly, but 5% had some information missing.

Collaborating with a third party brought another use of computer vision into the newsroom and showed what it could do in a different context. Coelho hopes this model could be used to monitor future elections and to encourage returning officers to fill out telegrams properly. “I think it’s good that the government knows you are using AI to find nuances in documentation,” she says.“We are being investigative journalists of technology… We are taking these projects and learning by doing with this lab.” — La Nacíon’s Florencia Coelho

Much of what they learned, Coelho says, can be applied to other types of music or even to different texts. “Today the topic was trap, but tomorrow we may use this for political discourse or for a different topic,” says data analyst Gabriela Bouret.

Bringing new technologies, reporting processes, and topics into play has pushed the newsroom too. “It was such a different thing to publish in La Nación,” Bouret notes. “It’s a very traditional newspaper and trap is especially for very young people. It’s totally different from what our audience expects from us and gets us out of the box.”

La Nación’s experiments are also exposing that AI has been built or trained for the English language and for audiences in the Global North. “Every [natural language processing] model has been prepared for the English language,” says Bouret. “It was very difficult for us to find the libraries and the processes to help us deal with the problem of the Spanish language [for the trap project].”

AI for Electoral Coverage

In 2021, the newsroom again used computer vision to detect errors in the telegrams returned from polling stations during parliamentary elections in Argentina.

Working with a third-party company to build and train an algorithm to identify inconsistencies in the telegrams, which record details including the number of votes won by each party and how many election monitors were present, human volunteers were then asked to sift through flagged records. La Nación used its existing VozData platform, where readers have collaborated on data investigations and worked with transparency initiatives and universities. Human helpers refined the algorithm: it had to be adjusted to deal with telegrams that were wonky or that had been uploaded upside-down. The results suggested that 95% of telegrams returned were filled out correctly, but 5% had some information missing.

Collaborating with a third party brought another use of computer vision into the newsroom and showed what it could do in a different context. Coelho hopes this model could be used to monitor future elections and to encourage returning officers to fill out telegrams properly. “I think it’s good that the government knows you are using AI to find nuances in documentation,” she says.“We are being investigative journalists of technology… We are taking these projects and learning by doing with this lab.” — La Nacíon’s Florencia Coelho

Finding Time for AI Projects

One of the biggest challenges for newsrooms looking to implement more AI projects is understanding the time it can take and protecting that time. There is no target for how many projects the lab produces in a year, it depends on the work involved and what other demands are placed on the team members’ time.

“These projects can take five to seven months — it’s long-term. It’s difficult for newsrooms to understand because they are always in a rush. You have to be patient. Once a week we have a meeting to work on this because if not, all of the other things will cover you,” says Bouret.

“Investigative journalists can spend a year looking into corruption or an event. We are being investigative journalists of technology,” adds Coelho. “We are taking these projects and learning by doing with this lab. Once we have enough information, we will be able to react in a faster way.”

Collaboration, whether with third-party AI specialists, university departments, or academic experts, can help newsrooms expedite the process and reduce the costs of introducing new technologies, says Coelho. Working with a newsroom may provide a real-life case study for a class or academic research, while start-ups may be interested in testing their tools and AI models to help news organizations solve a problem.

La Nación has also secured third-party funding for some of its AI work, including a Google News Initiative grant for a forthcoming machine learning project. Based on the idea of password strength checkers, the tool will make recommendations for journalists to improve wording related to diversity and inclusion.

A Focus on Gender and the Business SideA collaborative approach runs through all of La Nación’s AI projects and is exemplified by its team approach in the newsroom.

In La Nación’s experience, internal collaboration can also foster support for AI development within the organization and uncover more resources. The team is working on a Spanish-language version of the gender gap tracker, a tool originally devised to measure the ratio of female-to-male sources quoted in online news articles in Canadian media. Coelho and her colleague Delfina Arambillet began working on the project through the JournalismAI Collab project organized by the London School of Economics and has brought the work into La Nación’s newsroom to better understand gender biases in reporting, including whether a source’s gender affects the topics on which they are likely to be quoted. The resulting tool will be useful for the newspaper’s business insights team to assess how article performance is affected by the gender or topics featured.

In an extension of the gender tracker project, La Nación was also involved in an open source AI model developed to detect gender in faces to help analyze the ratio of male and female images used by news outlets. By sharing around 50 Argentinian and Latinx portraits with the team training the AI model, which was originally trained on Asian faces, the AI’s ability to detect a more diverse range of faces in terms of skin tone and ethnicity will improve, making it more useful to a wider range of newsrooms.

Whether with technology companies, commercial departments, other newsrooms, or audience volunteers, a collaborative approach runs through all of La Nación’s AI projects and is exemplified by its team approach in the newsroom. “The skills are so tough to learn that it’s better to learn them together even with competitors. Learn the skill together and then compete for the stories,” Coelho says. “We are already competing with Google and Facebook for the attention of our readers. It’s not good that we take five to 10 years to learn these things. We need to speed up the process of learning and radical sharing, and work with other countries. You will have to study too, but it’s too much for one person.”

Additional Reading

Journalists’ Guide to Using AI and Satellite Imagery for Storytelling

Deepfake Geography: How AI Can Now Falsify Satellite Images

AI in Journalism: With Power Come Responsibilities

Laura Oliver is a freelance journalist based in the UK. She has written for the Guardian, BBC, The Week, among others. She is a visiting lecturer in online journalism at City, University of London, and works as an audience strategy consultant for newsrooms.