JAPANESE CBW IN CHINA WWII

Devil's deal stole justice from dead

LONG READ

"A bomb filled with bacteria was placed on the ground and about 20 Manchurians were tied to poles (that is, enough distance to prevent men's death) from the bomb, which were electrically exploded. By the bomb blast ... and its fragments, the plague bacilli and anthrax bacilli penetrated through the wound into human bodies."

This shocking revelation came from Major Tomio Karasawa, 35, who was captured by the Russians in September 1945, in the final days of World War II. Karasawa was an army physician who between 1939 and 1944 worked in Unit 731, a covert biological research and development unit run by the Japanese Imperial Army.

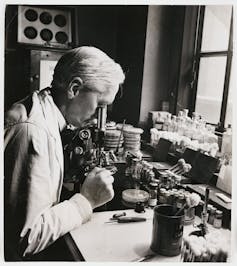

Unit 731, set up in 1932 by General Shiro Ishii, a microbiologist, in the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo in Northeast China, was responsible for some of the most notorious and little known war crimes in human history. (Manchukuo means the Empire of Manchus, for which the Japanese had installed the dethroned Qing Dynasty emperor Puyi, who was of Manchu ethnicity, as its figurehead ruler.)

The secret unity, based in Pingfang (which Western researchers often call Pinfan) just outside Harbin, the largest city of Manchukuo, and in what is today's Heilongjiang province, not only carried out human vivisections behind its high walls and produced vast quantities of germs to spread all over China, but also acted as an evil core for what the late US historian Sheldon H. Harris called "factories of death" that it had set up across Japan-occupied Asia.

The Russians, who acquired Karasawa's affidavit during their interrogations, soon brought it to the attention of the International Prosecution Section (IPS) of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), convened in April 1946 in Tokyo to try Japanese war criminals.

"We do not consider that the evidence now available is sufficient to justify an assurance that any of the accused can be associated with this activity by any of the criteria adopted by the Court with reference to atrocities and prisoners of war offenses," was the reply on Dec 13, 1946 from Frank S. Tavenner Jr, US associate prosecutor of the IPS.

Tavenner's phrase "Any of the accused" covered, among others, General Yoshijiro Umezu, who, between 1939 and 1944, was commander of the Kwantung Army that controlled Manchukuo, and a direct superior and chief supporter of Ishii. The army, together with the imperial army's military police army Kempeitai, ruled with an iron fist. The latter kept Ishii's laboratories supplied with captives-the Manchurians in Karasawa's affidavit, referred to internally as maruta, a Japanese word meaning logs, by those who performed vivisections.

The affidavit was never produced as evidence, nor was the man allowed to testify during court proceedings of the IMTFE, ostensibly modeled on the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg that tried Nazi war criminals.

Yet the affidavit was constantly brought up in written communications not only between the Americans and the Russians, the latter pushing for its inclusion in the trials, but also among the American prosecutors of the IPS, the military intelligence officials under General Douglas MacArthur's occupation authorities and those in Washington.

One of these declassified documents, kept at the US National Archives in College Park, Maryland, was an intelligence report dated Aug 1, 1947 and circulated within the State-War-Navy Coordinating Sub Committee for the Far East. (The State-War-Navy Coordinating Committee, a precursor to the US National Security Council, was a US federal government committee created in December 1944 to look at political and military issues related to the occupation of the Axis powers once World War II ended.)

The report, titled Interrogation of certain Japanese by Russian prosecutor, includes four appendixes. The Karasawa affidavit appears in Appendix A-"facts bearing on the problem". Elsewhere, the conclusion of the report is unequivocal:"The value to the US of Japanese BW (biological warfare) data is of such importance to national security as to far outweigh the value accruing from 'war crimes' prosecution."

This document can be found in the six-volume Compilation Of Historical Documents On Japanese Biological Warfare During WWII, published in 2019 and coedited by Wang Xuan, a Chinese researcher, and her Japanese counterpart Shoji Kondo.

"Imperial Japan's employment of biological weapons in China was full-scale, and unprecedented in human history," Wang, 69, said. "Its unspeakable cruelty can be glimpsed from the devil's deal, struck between Unit 731 scientists and the Americans who coveted their information."

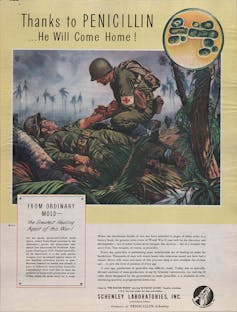

Ishii said that if the Americans could provide him and his associates with documentary immunity from prosecution for war crimes, much more would come their way. This would include "photomicrographs of selected examples of 8,000 slides of tissues from autopsies of human and animals subjected to BW experiments", as listed in Appendix A.

"Most distressing is the fact that the ultimate disclosure in the mid to late 1940s of Japanese BW human experimentation did not appall those individuals who were apprised of these criminal acts," wrote Harris in the preface of his groundbreaking book Factories Of Death: Japanese Biological Warfare, 1932-1945, and the American Cover-up. "Instead, the disclosure whetted the appetites of scientists and military planners among both the victors and the vanquished."

During Harris' research for the book in the late 1980s, he located in the Dugway Proving Ground Library three of the "20 huge autopsy reports relative to their (the Japanese's) experiment with humans". The Dugway Proving Ground, about 140 kilometers southwest of Salt Lake City, Utah, is a US Army facility established in 1942 to test biological and chemical weapons.

The Harris book, which Wang describes as "the very first comprehensive scholarly research that brings to light the American cover-up", was first published in 1994. The history professor at California State University, Northridge, would spend nearly all of his subsequent waking hours adding to it. A revised edition was published in 2002, shortly before he died in August that year.

Now, 20 years later, the Chinese version of the 2002 book is finally reaching shelves in China. Wang Xuan, who was closely involved with the translation of the 1994 book into both Japanese and Chinese, is also the chief translator of the revised 2002 edition.

The Chinese translation of another book on the same subject, Hidden Atrocities: Japanese Germ Warfare and American Obstruction of Justice at the Tokyo Trial, is also coming out, five years after it was published and a little more than two years after the death of its author Jeanne Guillemin, a medical anthropologist and senior fellow in the Security Studies Program at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Wang, who met Guillemin and her husband, the renowned American molecular biologist Matthew Meselson, in China in 2005, wrote the preface for the Chinese version.

"This coincidence, coupled with the sad deaths of the two scholars, both in their mid-70s, only serves to remind me of the physical and emotional toll taken of them as they wrestled with the dark truth," Wang said.

The Tokyo trial, which opened in May 1946, seven months after Japan surrendered and six months after the Nuremberg trials opened, proceeded in what Guillemin called "a radically different geopolitical context", one in which the United States, through General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, "ruled securely".

Yet it was what had been going on between the surrender and the opening of the trial that set the tone for the eventual miscarriage of justice.

In an interview with the Japan Times in 1982 Ishii's eldest daughter Harumi, then 57, said the first thing MacArthur did when he arrived in Japan on Aug 30, 1945 was to "inquire about my father".

No wonder so, according to Guillemin, even back in May 1944, MacArthur had already been informed of the discovery in a captured document of "a diagram of a Japanese Mark 7 experimental bacillus bomb, likely for anthrax and similar to munitions being developed by the United States and Britain". A US intelligence report dated Dec 15, 1944 included "a detailed map of an affiliate of Unit 731 located in Nanjing, called the Tama Unit (Unit 1644)".

In fact, two days before MacArthur arrived in Japan, Colonel Murray Sanders from Camp Detrick, Maryland, was already in Japan seeking out former Unit 731 scientists.

Sanders was to be followed by another three investigators from Camp Detrick (later Fort Detrick), the center of the US biological weapons program until 1969. These included Lieutenant Colonel Arvo Thompson, Sander's immediate successor.

Their investigations, mainly from a scientific point of view as military intelligence, were carried out simultaneously with the one done by the International Prosecution Section (IPS) of the IMTFE and the one by the Legal Section under the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (General MacArthur), both focused on the Japanese BW activities as war crimes.

A conflict of agendas was to erupt between what Harris dubbed "war crimes investigators" (the IPS prosecutors) and "BW/CW investigators" (Sanders and his successors). The latter, Harris wrote, "would brook no interference" from either "the issue of war criminal responsibility" or "medical or scientific ethics".

Around early March 1946, Thomas Morrow, US associate prosecutor of the IPS who was put in charge of investigating Japanese aggression in China, met Thompson and another investigator who was with G-2, the military intelligence division under MacArthur's occupation command. Morrow's request to interview Ishii, who had faked death before being located by MacArthur's intelligence, was turned down.

Then in a memo on June 4, Joseph Keenan, a Harvard graduate who had reportedly been handpicked by President Harry Truman to fill the role of IPS chief counsel, told all his staff at the IPS that a central interrogation center had been established under the control and direction of G-2, headed by Major General Charles A. Willoughby, a die-hard anti-Communist who would become a Cold War warrior. It was merely one month after the start of the Tokyo trial on May 3, 1946.

For those familiar with the entire trajectory of events, this arrangement, which in effect placed any further war crimes investigation under the control of US military intelligence in Tokyo, would be followed, later in trial, by directives from Washington to MacArthur that declared "information obtained from Ishii and associates on BW will be retained in intelligence channels and will not be employed as 'war crime' evidence."

In March 1946, while Morrow was being denied access to Ishii, Thompson was having extensive interviews with the man and his subordinates. In the same Japan Times interview, cited in the 2004 book A Plague Upon Humanity: The Hidden History of Japan's Biological Warfare Program by Daniel Barenblatt, Ishii's daughter Harumi recalled that Thompson "said he had come as an emissary for President Truman" and "literally begged my father for top-secret data on the germ weapons". (The Chinese translation of Barenblatt's book was published in 2016.)

For a month between March 12 and April 12, 1946, Morrow and David Nelson Sutton, US associate prosecutor and assistant to the Chinese Division of the IPS, were in China on a fact-finding mission. They were guided in this effort by Hsiang Che-chun (Xiang Zhejun), who had arrived in Tokyo in early February as head of the Chinese prosecution team and was behind Morrow's thwarted attempt to pursue the war crime.

On April 23, Sutton submitted to Keenan his final report, titled Report from China: Bacteria Warfare.

For Wang, her encounter with the Sutton report at the National Archives in Maryland in October 2010 was overpowering. "There I sat, amid the hushed quietness of the room, with tears running down my cheeks. Laid out in front of me were documents prepared by the Chinese prosecution for pursuing the Japanese BW war crime responsibility-they, and those before them, had really tried to bring those monsters to the bar. And I saw my hometown, listed in the documents as one of the places the Japanese had attacked with plague."

Among other things, enclosed in Sutton's report to Keenan is a report written by Peter Z. King (Jin Baoshan), a public health official with China's Nationalist Government, in late 1941. Citing the repeated appearances of low-flying Japanese aircraft dropping considerable quantities of "wheat grains, pieces of paper, cotton wadding and some unidentified particles" and the subsequent outbreak of bubonic plague in those areas, mostly plague-free until then, the report established a direct link between the four plague outbreaks and their subsequent spread in the provinces of Zhejiang and Hunan in 1940 and 1941 with Japan's biological warfare.

King's report was widely distributed in the spring of 1942 when China's foreign ministry notified all Allied embassies and legations that Japan's germ attacks were "ruthlessly in violation of the principles of international law and the principles of humanity". That protest fell on deaf ears.

During Sutton's trip to China, he interviewed King and, at his urging, spoke to W. I. Chen, a Chinese epidemiologist, and Robert Pullitzer, a plague prevention expert. Both were on site in Changde, Hunan province, soon after the plague started in November 1941 and wrote investigative reports corroborating King's claim. And both, like King, were more than willing to testify in court.

None was given the chance. In the last sentence of his report's covering letter to Keenan, Sutton wrote: "As the case now stands, in my opinion the evidence is not sufficient to justify the charge of bacterial warfare."

Wang was not impressed. "If this is not sufficient evidence, then the Chinese prosecution should be facilitated with access to chief suspects, instead of being withheld all information the US army investigators had been accumulating from Ishii and his associates," she said. "The Chinese prosecution had managed to come up with no less adequate proof for an indictment compared with other cases ongoing at the court. The nature of the crime deserves a thorough investigation."

It needs to be noted that Sutton, before being assigned assistant prosecutor at the IMTFE, was a civilian officer at the US Department of Defense with no background in biology, Wang said.

"I believe more information is needed if we are to interpret his actions, decisions and standpoint," said Wang, who met Hsiang, the Yale-educated Chinese prosecutor, in the late 1970s. Wang's father worked with Hsiang in the 1940s at the Shanghai High Court before the latter was appointed to the IMTFE.

By the time Wang stumbled upon the Sutton report in 2010, it had been three years since the end of a decadelong lawsuit in which she took a group of BW survivors from the attacked places in King's report to Japan, demanding compensation from the Japanese government. Wang's own paternal uncle died from bubonic plague following an airborne attack in Zhejiang in 1940."About 400 people, one-third of the population of my ancestral village, died," she said.

They died in unspeakably horrible conditions, as Patrick Tyler, a reporter for The New York Times, wrote in his 1997 story: "Their screams sundered the night from behind shuttered windows and bolted doors, and some of the most delirious victims ran or crawled down the narrow alleys to gulp putrid water from open sewers in a vain attempt to vanquish the septic fire that was consuming them."

According to Wang, the last time the Chinese prosecution appeared in Sutton's court working diary was on May 11, 1946, eight days after the start of the trial.

In this diary the assistant prosecutor said that two days earlier he found a note on his desk from Judge Hsiang. With the note, Hsiang had attached several translated pages of testimony from a Japanese soldier named Osamu Chimba (in Guillemin's book he is erroneously called C. C. H. Hataba due to a mistake from the original document), a former member of Unit 1644 (Tama Unit), a satellite of Unit 731 in Nanking (Nanjing).

Having deserted out of revulsion of his troops' "true, inhuman mission" in 1944-the only one to do so among the Japanese BW troops' 12,000 personnel, Chimba spoke about "a great scourge" inflicted on the Chinese provinces of Zhejiang and Jiangxi in May 1942 by Ishii and his scientists, whose powerful weapons, apart from plague, cholera, typhoid and dysentery bacteria, included anthrax.

The confessions of Chimba met with a similar fate as all other incriminating evidence-Sutton focused his attention on prosecuting the Japanese for the atrocities of the Nanking Massacre and "almost nothing concerning BW surfaced at the Far East International Military Tribunal's war crimes trials", Harris said.

However, in September 1946 the highly incriminating revelations of Major Karasawa and three other Soviet captives were brought to the attention of the Americans by those from the Soviet Division of the IPS, who demanded to interview Ishii for a potential war crimes trial.

If anything, this only served to convince the Americans of the value of their prize find and the need to keep him for themselves, away from the Russians with whom the decisionmakers in Washington believed they had entered a competition to develop the most powerful biological weapons.

"Up to that point, Ishii had consistently lied about the issue of human experiments, largely denying the fact that they had ever been conducted," Wang said. "Armed with the affidavits provided by the Soviets, the Americans, believing that they could exploit Ishii's fear of the Soviets to their own advantage, confronted the sly general, who then seized this opportunity to put forward his demand for the bargain-immunity from 'war crimes' in documentary form for himself, superiors and subordinates."

On May 6, 1947 MacArthur sent a top-secret radiogram to the War Department's General Intelligence Division, requesting action by the Joint Chiefs of Staff on an immunity agreement for the Unit 731 scientists.

In it, MacArthur said the affidavits from Karasawa and his superior Major General Kyoshi Kawashima had been "confirmed tacitly by Ishii", who "claims to have extensive theoretical high-level knowledge including strategic and tactical use of BW on defense and offense, backed by some research on best BW agents to employ by geographical areas of the Far East and the use of BW in cold climates".

The final deliberation from Washington is laid out bluntly in the Aug 1, 1947 intelligence report for circulation inside the US State-War-Navy Coordinating Sub-Committee for the Far East.

"This Japanese information is the only known source of data from scientifically controlled experiments showing the direct effect of BW agents on man... any war crimes trial would completely reveal such data to all nations, it is felt that such publicity must be avoided in the interests of defense and national security," the report said, noting at the same time that:"Experiments on human beings similar to those conducted by the Ishii BW group have been condemned as war crimes by the International Military Tribunal for the trial of major Nazi war criminals."

Showered by the Americans with gifts, Ishii, who at this point was regularly entertaining his US guests at home parties, encouraged his associates to speak freely with the investigators, who for their own part were occasionally shocked but often impressed by the candor of the Ishii scientists about the use of humans-Chinese, Koreans and Russians-in their research.

In August 1945, five days before Japan's official surrender, Ishii received a hand delivered message from Tokyo ordering him to eliminate all evidence of biological warfare "from the Earth forever". Yet before his escape home via Korea, before advancing Russian and Chinese troops, Ishii "managed to load three large wicker hampers with documents and specimens", Harris said. A large cache of salvaged biological warfare data and equipment was later sent from Pingfang to Busan, Korea and eventually to Japan.

What was put to instant demise were the lives of all remaining POWs-at least 3,000 had been experimented to death at Pingfang according to the confession by Kawashima but the actual number should be doubled based on the research of the Unit 731 Museum in Pingfang.

After the war Toshimi Mizobuchi, a veteran of Unit 731, said that on Aug 12, 1945, a fellow unit member came out of the Pingfang prisons and told him that he had "finished off 404 maruta (logs)", referring to the captives. The Russians later discovered in Pingfang a burned out compound with desperate pleas still discernible from scorched prison walls.

In a 1999 story by a New York Times reporter Ralph Blumentha l, Mizobuchi is depicted as "a vigorous 76-year-old real estate manager living outside the Japanese city of Kobe" who is "organizing this year's reunion for the several hundred surviving veterans of Unit 731". Ishii, before his death in 1959 of throat cancer, attended such reunions regularly with his former subordinates, a number of whom went into medical practice after the war.

On Nov 12, 1948, the IMTFE concluded. Of all the victims of the Imperial Japanese Army's biological warfare, the Tokyo trial records only contain the name of one-Kung Tsaoshang, who died of the plague attack in Changde in late 1941 and whose autopsy report, authored by Dr W. I. Chen, was passed to Sutton by King as part of the public health record.

"The delay in justice at Tokyo led to the denial of justice," wrote Guillemin in the final chapter of her book. Wang, who first went to Japan to study in 1987 before accidentally becoming involved in the decadelong lawsuit during her trip back home in 1994, had forcefully sought belated remedy.

On Aug 27, 2002, the Tokyo District Court admitted, for the first time in Japan's judiciary, that Unit 731 scientists had "used bacteriological weapons under the order of the Imperial Japanese Army's headquarters". That was four days before Harris, who spoke to the BBC about the court victory, died of a blood infection on Aug 31 in Los Angeles aged 74.

Although the same court ruled that postwar Sino-Japanese treaties prevented any compensation for the victims, its verdict was upheld by the Tokyo High Court in 2005 and by the Japanese Supreme Court in 2007, by which time 24 victim-plaintiffs had died.

"In 1998 Harris flew to Tokyo at the invitation of our Japanese lawyers' group, taking with him vast quantities of photocopied documents he had collected from US archives and elsewhere that could be of use to us,"Wang said. "I last met him in March 2002 in China, when I traveled with him and two US medical scientists to Zhejiang province to conduct research on victims of Japan's anthrax/glanders attack in 1942."

The same trip, the last one of Harris' 12 trips to China, also brought the three Americans to Wang's ancestral home in Yiwu, Zhejiang province, where a Tragedy Memorial Pavilion that listed the names of more than 1,000 plague victims in the county reduced them to tears. Wang led his guests through a gray-brick Buddhist temple with bare concrete floors, where in 1942 Japanese wearing white coats and masks dissected the infected villagers lured there by the lie that these men were doctors offering treatment.

The declassification of the Tokyo Trial documents, as well as intelligence documents generated by MacArthur's occupation authority and their communications with Washington, first started in the mid-1970s, following denunciation by the administration of President Richard Nixon of the offensive biological weapons program and improved relations with China.

In the late '80s and '90s more and more world media became interest-ed in Unit 731 history as an increasing number of repentant former unit members decided to come forward. Against this backdrop Harris published the first edition of his book in 1994, painstakingly combing through all declassified information, which he then augmented with the knowledge he acquired through special contacts within the US military and government.

Among those Harris inspired was Barenblatt, who, for his 2004 book, traveled to China and Japan many times, and had many long phone conversations with Wang, whom he called "one of the primal forces of nature".

The research also took Barenblatt, Harris' and Guillemin's fellow Harvard graduate, to a New York library where he discovered "a fragile old tome" with the title Materials on the Trial of Former Servicemen of the Japanese Army Charged with Manufacturing and Employing Bacteriological Weapons. The last time the book, a partial transcript of the 1949 war crimes trial of their captured Japanese medical scientists and military officers held by the Russians in the Siberian city of Khabarovsk, was checked out by anyone before Barenblatt had been in 1979.

At the Khabarovsk trial, which met with derision and denial in the West-Keenan, the IPS chief of counsel, denounced it as a Russian "show trial"-12 Japanese, including Karasawa, were convicted of conducting biological warfare or performing inhuman medical experiments. Karasawa, whom Wang believed was the first to speak about human experiments, was sentenced to 18 years' imprisonment and committed suicide when it was announced that he was to be released and repatriated to Japan with the other Japanese POWs in 1956.

In the preface of his revised edition, Harris cites a bill passed by the US Congress in 2000 that "mandates all government agencies to disclose any information held concerning actions of the Japanese Imperial Army that would constitute a war crime".

That work, by a government Interagency Working Group (IWG), did not start until May 2003, nine months after Harris' death. Lasting until March 2007, the declassification yielded 100,000 pages of materials on Japan's war crimes. Yet "there were still a lot of loopholes in the name of national security or to that effect", Barenblatt said.

In an email to China Daily, Yang Daqing, a history professor at Georgetown University who had acted as an IWG consultant, said: "Involved government agencies including the CIA sent their heads of their own in-house archives. While we historians could ask them to look for documents on certain subjects, these government officials shared with us what they found.

"We never heard that there were documents that could not be declassified. In theory those documents may exist, but I had no way of knowing."

In 2006, Barenblatt traveled to Changde, Hunan province, the site of a major Japanese plague attack in 1941, which led to more than 7,000 deaths. There, he met Yoshio Shinozuka, who worked at Unit 731's headquarters in Pingfang, where the germs spread in Changde were cultured and tested on victims.

One of those who had come to their conscience, Shinozuka testified in 2000 at court on behalf of the 180 Chinese led by Wang in their compensation lawsuit. Two years earlier in 1998, while trying to attend a photo exhibit on Unit 731 held in the US, he became the first former member of the unit who was turned away from entering the country.

In Changde for a conference on Japan's biological warfare, Shinozuka told Barenblatt how he, then 20 years old, helped prepare for dissection an "intelligent-looking man" who had been "systemically infected with plague germs" and whom he knew because "I had taken his blood once for testing".

"As the disease took its toll, his face and body became totally black. Still alive, he was brought on a stretcher by the special security forces to the autopsy room," said Shinozuka, who later washed the man's body with a rubber hose and a deck brush, under the watch of the chief pathologist.

"Shinozuka told me he'd never forget the glare of hate his victim directed at him as they were cutting into him," Barenblatt said. "One can't help but think what the victim must have been thinking toward the end of his life, that the world has got to know this."