Ukraine has led a public campaign, mostly through social media, appealing powerful tech institutions to end relationships with Russia.

By SOPHIE FOGGIN and HELEN LI

12 MARCH 2022

Here’s a list of all the tech companies taking action against Russia

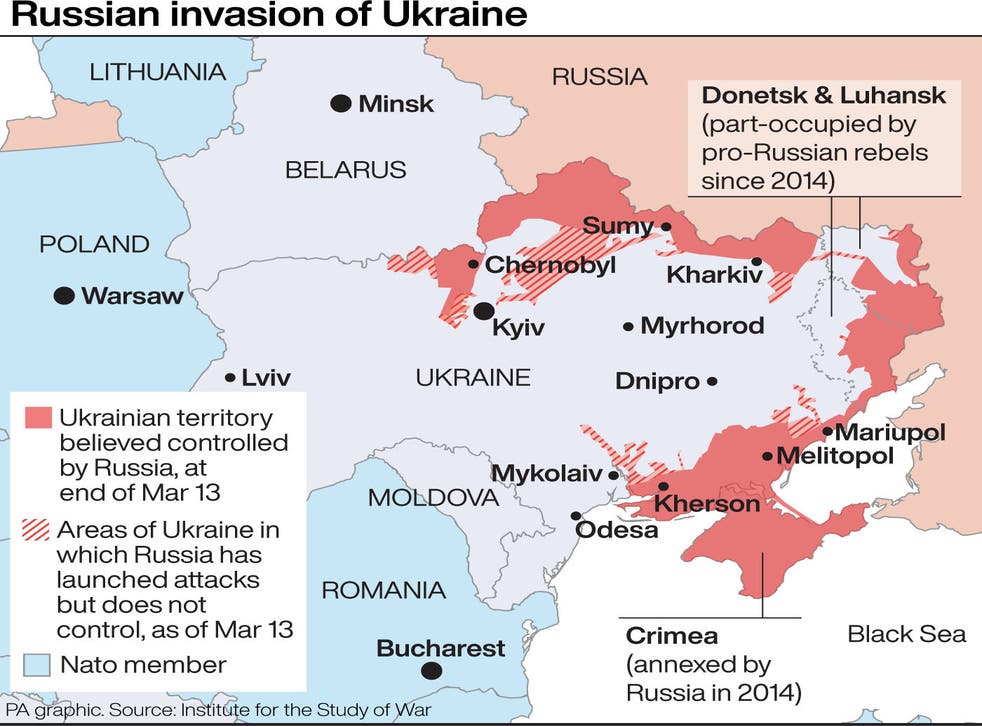

As the war in Ukraine rages on, with Russian forces edging closer to the capital, Kyiv, the global tech industry is joining governments and the international community in taking steps to punish Vladimir Putin. Dozens of companies, in Silicon Valley and around the world, are responding to Russia’s invasion by cutting the country off from their products, digital services, and systems.

We’ve put together a list of the companies that have taken action against Russia, and we’ll continue to update this in the days and weeks ahead.

Apple: The tech giant announced it will pause product sales in Russia due to its deep concern over the invasion of Ukraine. It has also limited access to its mobile payment service Apple Pay and restricted the availability of Russian state media apps, including RT and news agency Sputnik, for download outside of Russia. As a safety measure for Ukrainians, Apple has also disabled traffic and live incidents in Ukraine from Apple Maps.

Google: The company has removed Russian state-funded media, including RT, from its news-related features and the Google News search tool. It also paused Russian state media services’ ability to monetize through Google Ads on its websites and apps. In addition, it has banned Russian state media from using Google tools to buy ads and from placing ads on Google services, like Gmail. Google Pay, the company’s digital wallet, blocked several Russian financial institutions from its network.

Meta: The rebranded social network that owns Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp restricted access to RT and Sputnik within the EU and prohibited Russian state media from running ads or monetizing on its platforms anywhere in the world. Facebook also refused to stop fact-checking and labeling content from Russian state-owned news organizations — a move that the country called “censorship.”

YouTube: The Google-owned video-sharing website and social media platform paused Russian state media channels’ ability to make money through ads on videos.

Twitter: The social media network paused ads in Russia and Ukraine to ensure they don’t distract from public safety. (Meanwhile, Russia has restricted access to Twitter.)

TikTok: The video social media app TikTok restricted access to Russian state-controlled media accounts, including RT and Sputnik, in the EU. It also suspended its livestreaming services and content uploads from Russia, in the wake of the country’s “fake news” law that levies a punishment of up to 15 years in prison on those who publish false information about the military or publicly call for sanctions against Russia.

Netflix: The streaming platform has refused to air Russian state TV channels like Channel One on its streaming service. It later fully suspended service in Russia.

MIT: The Massachusetts Institute of Technology has cut ties with Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology, a Russian research university in Moscow.

TSMC: The world’s biggest semiconductor company, based in Taiwan, is halting chip sales to Russia, including Elbrus-branded chips designed in the country.

Intel: The American chipmaker halted sales to Russia.

AMD: Advanced Micro Devices also halted computer chip sales to Russia. Together with Intel, the two companies make up a large part of the desktop CPU market.

Dell Technologies: The computer maker vowed to suspend sales of its products in Russia and Ukraine, promising to closely monitor the situation to determine next steps.

Uber: The ride-hailing app is distancing itself from Russian ride-sharing service Yandex.Taxi and said it plans to “accelerate” the sale of its shares in the service.

Bolt: The European ride-hailing startup ceased operations in Belarus after Belarus supported Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Its delivery app, Bolt Market, removed “all products produced in Russia or associated with Russian companies.”

Snapchat: The social network said it will not display ads in Russia, Belarus, or Ukraine. The company also halted all ad sales in Russia and Belarus.

Viber: Japan’s Rakuten Group, the owner of the popular messaging app, said that it will remove advertising from its app in Russia.

Roku: The company, which makes streaming boxes for TVs, said it will ban Russia’s state-run news channel RT in Europe.

Microsoft: The tech giant said it will remove Russian state-owned media apps from its Windows app store and not run ads on state-owned media websites. It is also suspending all new product sales in Russia, which include Xbox consoles.

Electronic Arts: The major video game publisher said it will remove the Russian national team and Russian club teams from the most recent FIFA games. It will also remove Russian and Belarusian national and club ice hockey teams from the latest NHL game.

Nokia: The Finnish network equipment maker announced it will stop deliveries to Russia, in order to comply with sanctions imposed on the country.

Ericsson: The Swedish telecomms company will also suspend its deliveries to Russia, according to an internal memo from the company’s CEO reviewed by Reuters.

PayPal: The online payments company has stopped accepting new users from Russia. It had previously blocked some users and some Russian banks.

GoDaddy: The web hosting company no longer supports new registrations for domains with the .ru extension, which represents Russia.

Spotify: The music streaming service closed its Russia office “indefinitely” and removed all content by RT and Sputnik in Europe and other regions. It has also restricted shows “owned or operated by Russian state media.”

Oracle: The cloud services giant suspended operations in Russia following Ukrainian Vice Prime Minister Mykhailo Fedorov’s plea to the company to stop doing business in Russia “until the conflict is resolved.”

SAP: The German software corporation stopped sales of its products and services to Russia to align with sanctions against the country.

DuckDuckGo: The privacy-focused search engine paused its partnership with Russian search engine Yandex.

Reddit: The site banned users from posting links to Russian state-sponsored media outlets.

Airbnb: The platform halted operations in Russia and Belarus.

CD Projekt Red: The Polish game company announced that it will stop selling games in Russia and Belarus, including from its online game marketplace GOG.com.

Sony: The electronics giant is not releasing its flagship PlayStation driving game, Gran Turismo 7, in Russia.

Adobe: The software company stopped all of its sales and services in Russia. It also cut off Russian state media outlets’ access to Adobe Creative Cloud, Adobe Document Cloud, and Adobe Experience Cloud.

Coursera: The online course provider suspended all of its content from Russian universities and industry partners. It also stopped business with Russian institutions.

Samsung: The electronics giant suspended product shipments to Russia.

Siemens: The tech conglomerate suspended business in and deliveries to Russia.

HP: Russia’s largest PC supplier stopped exports to the country.

Sophie Foggin is a Colombia-based journalist covering human rights and social issues.

Helen Li is the producer of Fresh Off the Vote, a podcast on politics and civic engagement among Asian American youth.