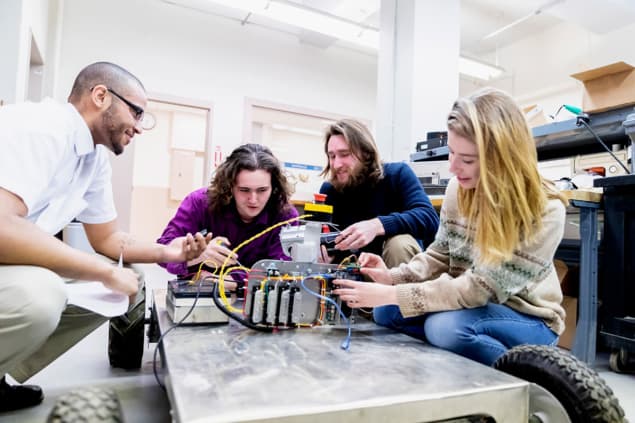

Lab gender roles not due to personal choice, finds study

Male and female preferences for carrying out certain tasks during experimental laboratory work are largely the same – and do not support stereotypical gender roles that are often seen in lab settings. That is according to a study carried out by Natasha Holmes from Cornell University and colleagues, who say the tasks that students choose to do in inquiry-based lab sessions could be due to biases and different levels of confidence among men and women.

The new study follows on from research published by the same team in 2020, which found that when students make their own decisions about experimental design in inquiry-based lab sessions, male students are more likely to handle equipment while female students spend more time taking notes and in communication roles. This gender disparity seemed to develop implicitly, as individuals were not allocated roles by instructors, and group members rarely discussed which tasks they would each be doing.

To find out if the students’ personal preferences for different tasks might be driving this trend, in the new study the researchers conducted interviews with undergraduate students followed by a survey. Out of 100 individuals, the researchers found that male and female preferences for each of the tasks were largely the same. Crucially, female students expressed a similar level of preference for handling the equipment as that of male students.

The 2020 paper found that this gender bias appears in inquiry-based lab sessions, but not in traditional lab sessions, which are more structured, with students being given instructions for how to carry out the experiments. This difference presents a conundrum for the researchers as they have previously found that inquiry-based labs boost students’ engagement and encourage them to take more “ownership” of their learning, compared with traditional labs.

“We think the gendered behaviours emerge during that subtle, collegial volunteering,” Holmes told Physics World. “We think the bias is related to students’ desire to be friendly and not wanting to argue with group mates who volunteer for certain roles, as well as male and female students having different levels of initial confidence to jump into a particular role.”

Holmes and colleagues are now focussing on how to retain the educational benefits of inquiry-based labs while reducing the likelihood of gender bias emerging. “Although this study ruled out an important hypothesis, we have a lot more questions now,” she says. “We’re planning to test out different instructional interventions to see what is most effective.”

Those include assigning roles to the students and instructing them to rotate during the session or between labs; having open discussions about how some students might be more comfortable jumping into the equipment roles; and having students write down in their experiment designs how they are all going to contribute. “We think that this will make them explicitly reflect on ways to get everyone involved and make effective use of their group members,” adds Holmes.

A block with a carved foot found on the edge of Motya’s sacred pool probably was part of a statue of a Phoenician god that originally stood on a pedestal at the pool’s center, researchers say.L. NIGRO/ANTIQUITY 2022

A block with a carved foot found on the edge of Motya’s sacred pool probably was part of a statue of a Phoenician god that originally stood on a pedestal at the pool’s center, researchers say.L. NIGRO/ANTIQUITY 2022