MEN ARE SNOWFLAKES BC MUST BE 100% SAFE

New Male Birth Control Pill Effectively Prevents Pregnancy – Without Side Effects

Women have many choices for birth control, ranging from pills to patches to intrauterine devices, and partly as a result, they bear most of the burden of preventing pregnancy. But men’s birth control options — and, therefore, responsibilities — could soon be expanding. Today, scientists report a non-hormonal male contraceptive that effectively prevents pregnancy in mice, without obvious side effects.

The researchers presented their results this week at the spring meeting of the American Chemical Society (ACS). ACS Spring 2022 is a hybrid meeting that was held virtually and in-person March 20-24, with on-demand access available March 21-April 8. The meeting features more than 12,000 presentations on a wide range of science topics.

Currently, men have only two effective options for birth control: male condoms and vasectomy. However, condoms are single-use only and prone to failure. In contrast, vasectomy — a surgical procedure — is considered a permanent form of male sterilization. Although vasectomies can sometimes be reversed, the reversal surgery is expensive and not always successful. Therefore, men need an effective, long-lasting but reversible contraceptive, similar to the birth control pill for women.

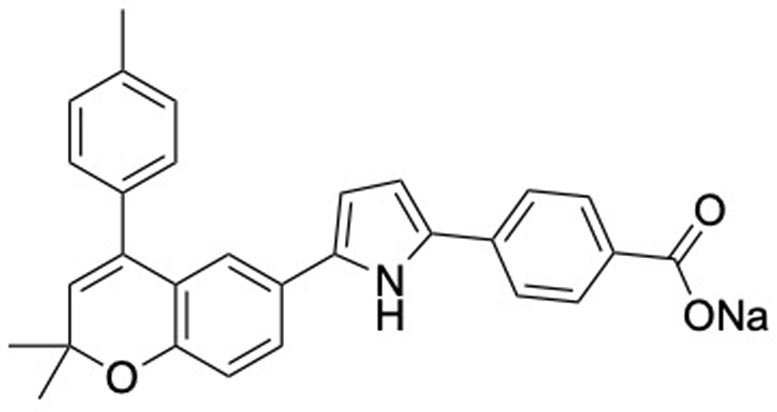

A non-hormonal male contraceptive (known as YCT529; structure shown here) prevents pregnancy in mice by blocking a vitamin A receptor, with no obvious side effects. Credit: Md Abdullah Al Noman

“Scientists have been trying for decades to develop an effective male oral contraceptive, but there are still no approved pills on the market,” says Md Abdullah Al Noman, who is presenting the work at the meeting. Most compounds currently undergoing clinical trials target the male sex hormone testosterone, which could lead to side effects such as weight gain, depression and increased low-density lipoprotein (known as LDL) cholesterol levels. “We wanted to develop a non-hormonal male contraceptive to avoid these side effects,” says Noman, a graduate student in the lab of Gunda Georg, Ph.D., at the University of Minnesota.

To develop their non-hormonal male contraceptive, the researchers targeted a protein called the retinoic acid receptor alpha (RAR-a). This protein is one of a family of three nuclear receptors that bind retinoic acid, a form of vitamin A that plays important roles in cell growth, differentiation (including sperm formation) and embryonic development. Knocking out the RAR-a gene in male mice makes them sterile, without any obvious side effects. Other scientists have developed an oral compound that inhibits all three members of the RAR family (RAR-a, -ß and -?) and causes reversible sterility in male mice, but Georg’s team and their reproductive biology collaborators wanted to find a drug that was specific for RAR-a and therefore less likely to cause side effects.

So the researchers closely examined crystal structures of RAR-a, -ß and -? bound to retinoic acid, identifying structural differences in the ways the three receptors bind to their common ligand. With this information, they designed and synthesized approximately 100 compounds and evaluated their ability to selectively inhibit RAR-a in cells. They identified a compound, which was named YCT529, that inhibited RAR-a almost 500 times more potently than it did RAR-ß and -?. When given orally to male mice for 4 weeks, YCT529 dramatically reduced sperm counts and was 99% effective in preventing pregnancy, without any observable side effects. The mice could father pups again 4-6 weeks after they stopped receiving the compound.

According to Georg, YCT529 will begin testing in human clinical trials in the third or fourth quarter of 2022. “Because it can be difficult to predict if a compound that looks good in animal studies will also pan out in human trials, we’re currently exploring other compounds, as well,” she says. To identify these next-generation compounds, the researchers are both modifying the existing compound and testing new structural scaffolds. They hope that their efforts will finally bring the elusive oral male contraceptive to fruition.

The researchers acknowledge support and funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Male Contraceptive Initiative. Georg is a consultant with YourChoice Therapeutics.

Title

Development of selective RARa antagonists as male contraceptive agents

Abstract

The quest for an effective male contraceptive agent has begun decades ago with no approved pills to date. Compounds undergoing clinical trials are all targeted on male sex hormone testosterone which could lead to hormonal side effects such as weight gain, depression, increased low-density lipoproteins, etc. Our effort focused on developing a non-hormonal male contraceptive to avoid the hormonal side effects. Vitamin A has long been known to be essential for male fertility and vitamin-A-deficient diet causes mammalian male sterility. One particular receptor of vitamin A metabolite retinoic acid (RARa) is validated as the target for male contraception by gene knockout studies. Also, oral administration pan-RAR antagonist BMS-189453 which inhibits the activity of RAR a, ß, and ? lead to reversible sterility in male mice. Knocking out RAR alpha and treatment with a pan-RAR antagonist did not present any significant side effects in mice. We pursued to develop a selective RARa antagonist as a safe, effective, and reversible male contraceptive agent with no off-target effects on RARß and RAR?. Based on the published crystal structures of RARa-ligand complex as well as structures elucidated by us, we envisioned to exploit the structural differences between RARa, ß, and ? ligand-binding domain to achieve RARa selectivity. Also, the structural differences between RARa bound to the agonist and the antagonist facilitated the design of full antagonists. Aided by all the structural information, we designed and synthesized about 100 compounds and evaluated RARa antagonist activity and selectivity using a luciferase-reporter cell assay. We obtained several antagonists with single-digit nanomolar IC50 values for RARa with excellent selectivity over RARß and RAR?. One RARa-selective antagonist showed good oral bioavailability and desired pharmacokinetic properties in mice, and upon oral administration, it showed complete inhibition of embryo formation in mating studies. Modification of active compounds is ongoing to obtain additional potent and selective inhibitors with good pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties.