Wall Street bonuses soar by 20%, nearly 5 times the increase in US average weekly earnings

Due to Washington inaction, millions of essential workers continue to earn poverty wages, while the reckless bonus culture is alive and well on Wall Street.

While inflation has wiped away wage gains for most U.S. workers, just-released data reveal that Wall Street employees are enjoying their biggest bonus bonanza since the 2008 crash.

Institute for Policy Studies analysis of new New York State Comptroller bonus data:

The Inflation Divide

- The average annual bonus for New York City-based securities industry employees rose 20 percent to $257,500 in 2021, far above the 7 percent annual inflation rate. By contrast, typical American workers lost earnings power in 2021. Average weekly earnings for all U.S. private sector employees rose by only 2 percent between January 2021 and January 2022, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Unlike hourly wage data, average weekly earnings reflect the fact that many Americans had to cut back on work hours last year, largely due to Covid-related illness, lack of child care, and other family care pressures. The average weekly hours worked by U.S. private sector employees dropped from 35.0 to 34.5 between 2020 and 2021.

Return to Pre-Financial Crash Bonus Levels

The average Wall Street bonus of $257,500 in 2021 was far higher than any year since the 2008 financial crash. The second-highest was the 2017 average bonus of $209,046, adjusted for inflation. These bonuses come on top of base salaries, which averaged $254,000 in 2020.

Wall Street pay v. the minimum wage

- Since 1985, the average Wall Street bonus has increased 1,743 percent, from $13,970 to $257,500 in 2021 (not adjusted for inflation). If the minimum wage had increased at that rate, it would be worth $61.75 today, instead of $7.25.

- The total bonus pool for 180,000 New York City-based Wall Street employees in 2021 was $45 billion — enough to pay for more than 1 million jobs paying $15 per hour for a year.

Wall Street bonuses and gender and racial inequality

The rapid increase in Wall Street bonuses over the past several decades has contributed to gender and racial inequality, since workers at the low end of the wage scale are disproportionately people of color and women, while the lucrative financial industry is overwhelmingly white and male, particularly at the upper echelons.

- The share of the five largest U.S. investment banks’ senior executives and top managers who are male: JPMorgan Chase: 74%, Goldman Sachs: 75%, Bank of America: 64%, Morgan Stanley: 74%, and Citigroup: 64%.

- In 2021, the leadership of the largest Wall Street banks became slightly more diverse when Jane Fraser, a white woman, became the first female leader of a top-tier U.S. investment bank. The CEOs of the other four banks in that tier are all white males.

Nationwide, men make up 62 percent of all securities industry employees but just a tiny fraction of workers who provide care services that are in high demand but continue to be very low paid. Men make up just 5.4 percent of childcare workers, an occupation that pays $26,790 per year, on average. Men make up just 13 percent of home health aides, who average $27,080 per year.

- At the five largest U.S. investment banks, the share of executives and top managers who are Black: JPMorgan Chase: 5%, Goldman Sachs: 3%, Bank of America: 5%, Morgan Stanley: 3%, and Citigroup: 4%.

- Nationally, Black workers hold just 7.2 percent of lucrative securities industry jobs but 27.4 percent of home care and 16.3 percent of child care jobs.

These jaw-dropping numbers are just the latest evidence of unequal sacrifice under the pandemic. While ordinary workers are struggling with rising costs for basic essentials, Wall Street bankers have seen their bonuses rise further into the stratosphere.

Actions to crack down on runaway Wall Street pay are long overdue. Since 2010, the year the Dodd-Frank financial reform became law, regulators have failed to implement that law’s Wall Street pay restrictions. Meanwhile, Congress has failed to raise the minimum wage.

“These two failures speak volumes about who has influence in Washington — and who does not,” Anderson said.

Powerful Wall Street lobbyists have succeeded in blocking Section 956 of the Dodd-Frank legislation, which prohibits large financial institutions from awarding pay packages that encourage “inappropriate risks.” Regulators were supposed to implement this new rule within nine months of the law’s passage but have dragged their feet — despite widespread recognition that these bonuses encouraged the high-risk behaviors that led to the 2008 financial crisis, costing millions of Americans their homes and livelihoods.

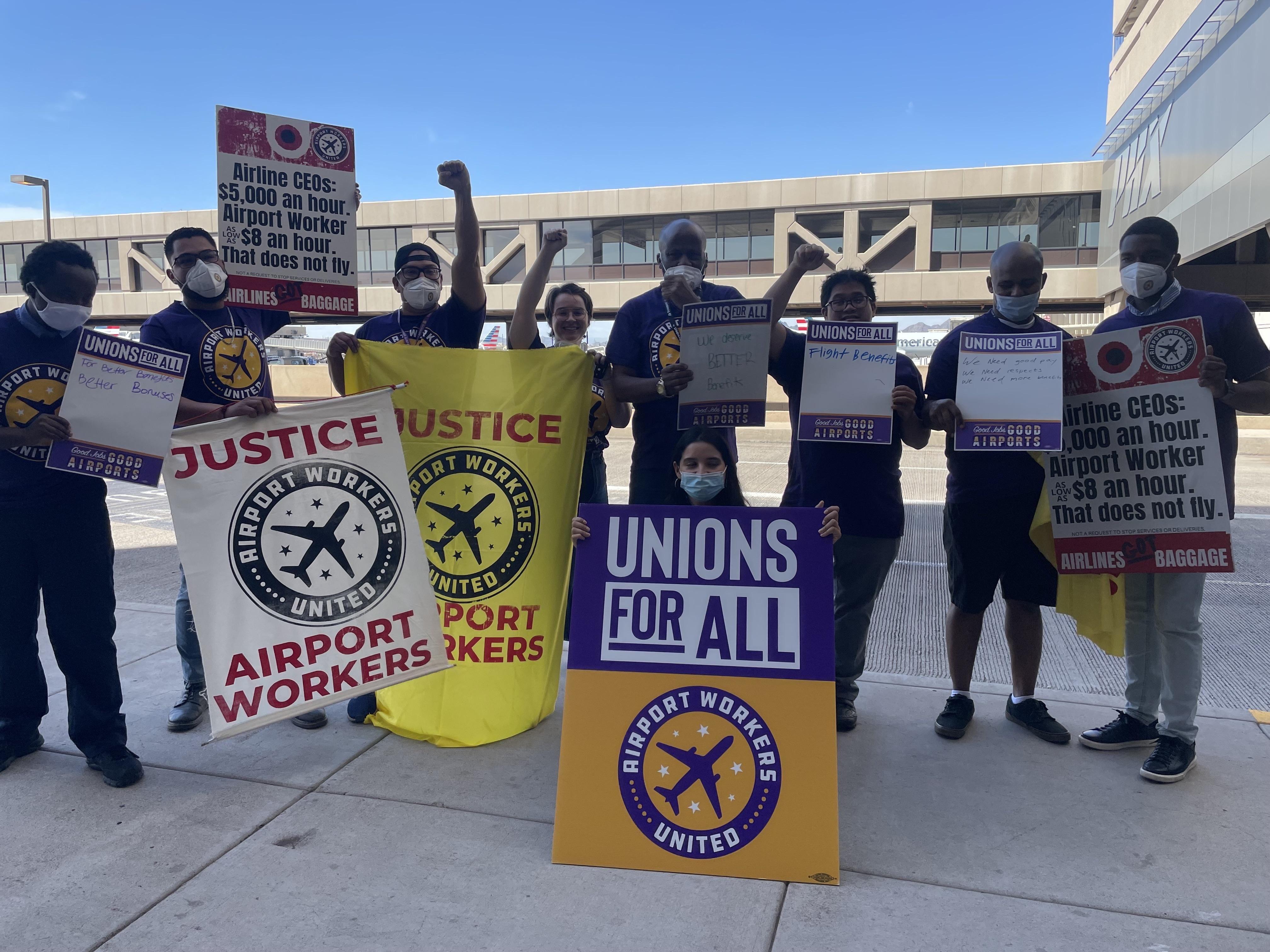

In contrast to the Wall Street lobbyists, advocates for the working poor have seen their efforts to raise the federal minimum wage and secure other important worker benefits stalled in Congress. Due to Washington inaction, millions of essential workers continue to earn poverty wages, while the reckless bonus culture is alive and well on Wall Street

‘Jaw-dropping’: Wall Street bonuses have soared 1,743% since 1985

A new analysis finds that if the federal minimum wage had increased at the same rate, it would currently be $61.75 an hour.

A new analysis out Wednesday estimates that if the federal minimum wage had grown at the same rate as Wall Street bonuses over the past three and a half decades, it would currently be $61.75 an hour instead of $7.25.

According to fresh data from the New York State Comptroller, the average bonus dished out to Wall Street employees jumped 20% to a record $257,500 in 2021 as big banks reported huge profits despite widespread havoc caused by the coronavirus pandemic. Last year’s average Wall Street bonus was the highest since 2006, prior to the Great Recession.

The comptroller’s office points out that while the securities industry comprises just 5% of private-sector employment in New York City, it makes up one-fifth of total private-sector wages.

Taking the new figures into account, Sarah Anderson of the Institute for Policy Studies notes in a report that the average Wall Street bonus has soared by 1,743% since 1985.

“By contrast, typical American workers lost earnings power in 2021,” Anderson writes, noting that high inflation has eroded the modest wage gains seen by ordinary people. “Average weekly earnings for all U.S. private-sector employees rose by only 2% between January 2021 and January 2022, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.”

“These jaw-dropping numbers are just the latest evidence of unequal sacrifice under the pandemic,” Anderson adds. “While ordinary workers are struggling with rising costs for basic essentials, Wall Street bankers have seen their bonuses rise further into the stratosphere.”

Anderson argues that Wall Street bonuses have been soaring in recent years partly because Section 956 of the Dodd-Frank Act—a financial reform measure enacted in the wake of the 2008 crash—has never been implemented.

“Powerful Wall Street lobbyists have succeeded in blocking Section 956… which prohibits large financial institutions from awarding pay packages that encourage ‘inappropriate risks,'” Anderson writes. “Regulators were supposed to implement this new rule within nine months of the law’s passage but have dragged their feet—despite widespread recognition that these bonuses encouraged the high-risk behaviors that led to the 2008 financial crisis, costing millions of Americans their homes and livelihoods.”

“In contrast to the Wall Street lobbyists, advocates for the working poor have seen their efforts to raise the federal minimum wage and secure other important worker benefits stalled in Congress,” she continues. “Due to Washington inaction, millions of essential workers continue to earn poverty wages, while the reckless bonus culture is alive and well on Wall Street.”