This 900-Mile Crude Oil Pipeline Is a Bad Deal for My Country — and the World

April 8, 2022

Chalk drawings from a protest in Johannesburg, South Africa,

By Vanessa Nakate

Vanessa Nakate is a Ugandan climate justice activist.

KAMPALA, Uganda — This week, the panel of climate experts convened by the United Nations delivered a clear message: To stand a chance of curbing dangerous climate change, we can’t afford to build more fossil fuel infrastructure. We must also rapidly phase out the fossil fuels we’re using.

In moments like this, the media rarely focuses on African countries like mine, Uganda. When it does, it covers the impacts — the devastation we are already experiencing and the catastrophes that loom. They are right to: Mozambique has been battered in recent years by cyclones intensified by climate change. Drought in Kenya linked to climate change has left millions hungry. In Uganda, we are now more frequently hit by extreme flash floods that destroy lives and livelihoods.

But this latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, on how to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and prevent more of these impacts, has implications for Africa’s energy systems, too. Africa isn’t only a victim of the climate crisis, but also a place where infrastructure decisions made in the coming years will shape how it unfolds.

TotalEnergies, a French energy company, this year announced a $10 billion investment decision, which involves a nearly 900-mile oil pipeline from Kabaale, Uganda, to a peninsula near Tanga, Tanzania. From there, the oil would be exported to the international market.

Despite local opposition, TotalEnergies and a partner, the China National Offshore Oil Corporation, have pushed ahead. The project might have a difficult time securing additional financing, as many banks have already ruled out the project. The multinational insurance company Munich Re has also vowed not to insure it, at least in part because of the harm it would do to the climate.

Burning the oil that the pipeline will transport could emit as much as 36 million tons of carbon dioxide per year, according to one estimate. That is roughly seven times the total annual emissions of Uganda.

More immediately, the East African Crude Oil Pipeline will have terrible consequences for people in Uganda and Tanzania. An estimated 14,000 households will lose land, according to Oxfam International, with thousands of people set to be economically or physically displaced. There are reports that compensation payments offered to some communities are completely insufficient. The pipeline will also disturb wildlife habitats. The climate writer and activist Bill McKibben said that it looks almost as if the route had been “drawn to endanger as many animals as possible.” An oil spill would be even more catastrophic for habitats and our freshwater supplies. (TotalEnergies and the China National Offshore Oil Corporation previously said they are working to avoid causing damage to the countries.)

Oil pipelines have become a symbol around the world of the fight for climate justice. In 2021 the Biden administration halted the Keystone XL pipeline in the United States after a decade-long fight led by Indigenous groups, climate activists and farmers. In East Africa the Stop EACOP campaign is a similar alliance that has emerged to fight fossil fuel infrastructure. Over a million people have signed a petition calling on TotalEnergies and the pipeline’s other backers to stop the project.

However, the Ugandan government remains largely in favor of the pipeline. Politicians have seemingly bet their political futures on the promise of revenues it could generate. Understandably, many people in Uganda not directly affected by the pipeline also think the oil could be a door to wealth. Our country has low levels of formal employment, and many people struggle to feed their families. Oil was discovered in the Lake Albert basin in 2006, when I was in primary school, and I remember my teacher proudly announcing to the class that Uganda had found “black gold.”

But the discovery of oil in Nigeria, Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo has not brought widespread prosperity. Instead, it has brought poverty, violence and the loss of traditional lands and cultures. Much of the profits have gone to foreign multinationals and investors and to the pockets of corrupt local officials. TotalEnergies and the China National Offshore Oil Corporation will own 70 percent of the East African Crude Oil Pipeline, with Uganda and Tanzania sharing the remaining 30 percent. This pipeline is not an investment for the people.

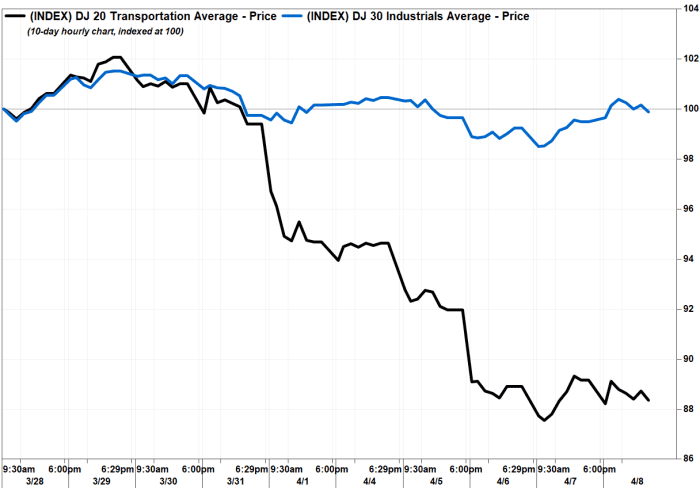

It is also not an investment for the long term. The International Energy Agency projects that growth in renewable energy will accelerate in the next four years. Fossil fuel projects like EACOP could lead to short-term gains but eventually huge losses — and might end up among the estimated $1.3 trillion of stranded oil and gas assets by around 2050.

Research presented by the International Renewable Energy Agency found that sub-Saharan Africa can meet almost 70 percent of its electricity needs from local renewable energy by 2030, which would provide up to two million additional green jobs in the region by 2050. Africa possesses 39 percent of the world’s potential for renewable energy, according to Carbon Tracker, but along with the Middle East, receives only 2 percent of annual investment. Africa needs the climate financing it has been promised by rich countries, as well as from private institutions, to develop clean energy.

There is a huge appetite for clean energy alternatives here. I have seen it through my work to install solar panels and clean stoves in rural schools. These efforts sometimes feel hopeless when money floods in from foreign banks and governments for fossil fuels. But Africa is where critical investments should go in our fight for a stable climate in the coming years. Financial institutions must reject the East African Crude Oil Pipeline and fossil fuel projects like it, in favor of clean energy. The science is clear. So is the case for investment.