Who's drawn to fascism? Postwar study of authoritarianism makes a comeback

The Authoritarian Personality was first published in 1950 and is widely studied now

By most accounts, 2021 was a terrible year for democracy, from the attack on the U.S. Capitol to the rolling back of civil liberties in India. Liberal democracies are being challenged — from within and without — and many expect authoritarian rule to continue to metastasize in 2022.

Some scholars believe that a book published over 70 years ago — The Authoritarian Personality — could help researchers, and many of us today, grapple with troubling political trends in our own era.

"We see so many variations of right-wing populism, of authoritarianism, of neo-fascism around the globe that a book like this has gained, unfortunately, new relevance," said Peter E. Gordon, professor of history at Harvard University, who wrote the introduction to a new edition of The Authoritarian Personality published on its 70th anniversary.

Whether something like fascism could persist or re-emerge was something that concerned them deeply.- Peter E. Gordon

The lead author of the study was Theodor Adorno, a German philosopher and leading member of the Frankfurt School of social theory and critical philosophy. His three co-authors were: psychologist Else Frenkel-Brunswik, who fled anti-Jewish persecution in both Poland and Austria in the 1930s; University of California psychology professor, R. Nevitt Sanford; and PhD student Daniel J. Levinson, researcher into the psychology of ethnocentrism.

"These four individuals brought to their study a very deep concern about the future of democracy in Europe and also in America," according to Gordon.

"The question as to whether something like fascism could persist or re-emerge was something that concerned them deeply."

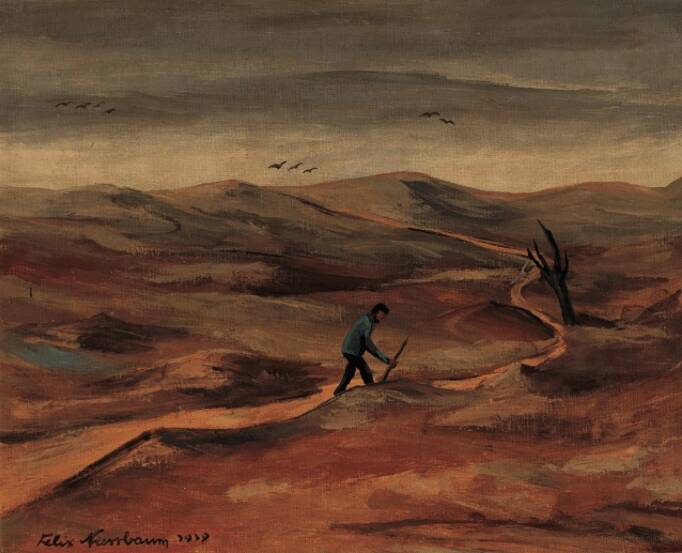

Adorno and Frankel-Brunswick were both directly affected by Nazi Germany's antisemitism. Adorno's father, for example, was brutalized by the Gestapo. Both scholars were living in exile in southern California in the 1940s, part of a community of German émigrés living in and around a tiny neighbourhood of Pacific Palisades, which one writer once dubbed "Weimar on the Pacific."

The F-scale

The four scholars surveyed 2,000 people living in southern California in 1945 and 1946.

"They want to figure out how do otherwise fairly normal individuals get drawn into radical-right authoritarian movements," said Gordon, but he warned that The Authoritarian Personality is often misunderstood.

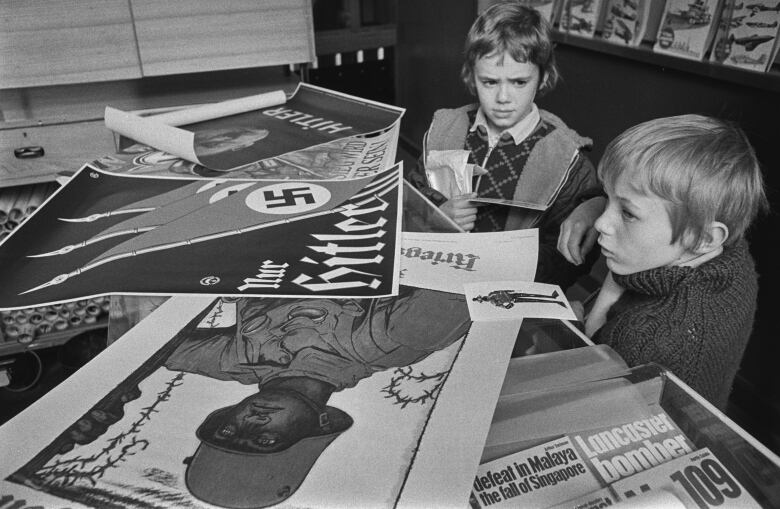

"It's not a study of what causes fascism… it's a study of what they call the potentially fascist individual, by which they mean they want to figure out: what is it that makes someone susceptible to fascist propaganda?"

To answer that question they came up with questionnaires to determine where participants fell along four different scales: the antisemitism scale; the ethnocentrism scale; the political-economic conservatism scale; and the best-known, F-scale, to test for fascism.

The original F-scale questionnaire included 77 questions to test for a person's susceptibility to fascist propaganda. Participants were asked how much they agreed or disagreed with a series of statements. For example: "obedience and respect for authority are the most important virtues children should learn" and "the businessman and the manufacturer are much more important to society than the artist and the professor."

A subset of the study participants also underwent in-depth interviews, informed by Freudian psychoanalysis and the belief that relationships between children on the one hand, and parents and authority figures on the other were key to the shaping of a person's personality.

"Each of the questions was designed to help the researchers determine how much the subjects of the study were influenced by a kind of deep bias toward a world that is unchangeable," said Kathy Kiloh, associate professor at OCAD University and the co-founder of The Association for Adorno Studies.

"Where the study is going here is the idea that we need to recognize that this reliance upon authority, it goes deep. It goes very deep."

When the nearly 1,000-page study was published in 1950, it rocked the academic world. But it soon fell out of favour. Kiloh says The Authoritarian Personality was seen as "too dark," overly Freudian and simply not relevant for the times.

During the post-war economic boom, democratic optimism ran high. "This book became one of merely historical interest because the scale was plotting something that people thought belonged purely to the past," said Gordon.

Revival of the authoritarian personality

Donald Trump's entrance onto the political scene on June 16, 2015 was a turning point. That day he descended a golden escalator at Trump Towers in New York City and declared: "the American Dream is dead; I will bring it back" and announced he was running to be leader of the Republican party and president of the United States.

Matthew MacWilliams was shocked by what he saw.

"I watched Trump come down and then I listened to the speech and I said: that was an authoritarian speech," he said. "I've never heard anything like that in America."

MacWilliams wondered if Trump were "activating" authoritarians in his party. To find out, he conducted a poll of Republican primary voters and found that those with authoritarian leanings were much more likely to prefer Trump.

"Even when you put in education and other big, big variables that should soak up all of the predictability of the variable," said MacWilliams, "and it didn't for any other candidate. Ted Cruz, nope. Marco Rubio, nope. It was Donald Trump."

MacWilliams wrote an op-ed arguing that Trump appealed to people with authoritarian tendencies in the party. The article went viral. It also triggered a backlash and MacWilliams received threats.

"It sort of fits with that American exceptionalism that somehow we came across in our little boats and during that long voyage, we were washed of all authoritarianism. And the fact is, no, that didn't happen," said MacWilliams.

"The institutions and the politics aren't responding to the threat because they still think it can't happen here."

The poll MacWilliams conducted — and the questions he asked to test for authoritarian leanings — drew on the intellectual history and tradition that infused The Authoritarian Personality. Although work on authoritarianism fell out of fashion in academic circles, a small group of scholars kept working to address the original study's methodological shortcomings and biases.

Testing for authoritarianism today

Rather than the long list in the original F-scale questionnaire, researchers today are asking four to eight simple questions, none of them directly about politics. They're parenting questions, designed to get a sense of a person's relationship with authority. The original F-scale questionnaire included several questions about parenting that are quite similar to the questions being asked by researchers today.

These four questions have been asked around the world by MacWilliams and other scholars.

F-scale used for parenting

People have different ideas about the ways that children should be raised. Here are four pairs of attributes that are considered:

- Independence or Respect for Elders

- Curiosity or Good Manners

- Self-Reliance or Obedience

- Being Considerate or Being Well-Behaved

"The thing about the questions [is] they have nothing to do with politics or political behaviour," said MacWilliams. "And that's what makes them so powerful. Because it isn't like I ask: do you think we need a strong leader to ignore the Constitution and Parliament? Yes, I do! Oh, you might be an authoritarian!... But we know it's out there. We can observe it. These questions are our filter for observing it. They aren't perfect, but they're really good at what they're doing."

Of course, most parents value all eight attributes and encourage them in their children.

"What's interesting is what happens when you force people to make a choice to prioritize," said Jonathan Weiler, professor of global studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and co-author of Prius or Pick Up: How the Answers to Four Simple Questions Explain America's Great Divide.

"When people do prioritize, when they are forced to make a choice, the choices they make have an incredibly powerful relationship to their views about gay marriage, about race, about gender in society, about politics more broadly."

Scholars like Jonathan Weiler and Matthew MacWilliams have found that about 25 per cent of the American population are on the non-authoritarian end of the spectrum, 35 per cent are somewhere in the middle and 30-35 per cent are on the authoritarian end of the scale.

Weiler says those numbers haven't changed much over the years. What has changed is the relationship between a person's worldview and their politics. Politics used to be about the role of the state and the size of government.

Now it's much more about feelings, according to Weiler.

A new, highly emotional partisan divide has opened up in this era of polarization and it's apparent in the evolution of how Americans answer the four parenting questions.

"When these questions were first being asked in 1992, there was a pretty even split among Democrats between those who answered these questions in an authoritarian direction and those who answered them in a non-authoritarian direction," he said.

But all of that had changed by 2020.

"People who identified as Democrat were far more likely to answer these parenting questions in a non-authoritarian way and people who identified as Republican were far more likely to answer these questions in an authoritarian way."

Frank Graves is president and founder of Ekos Research Associates and an adjunct professor in the Department of Sociology at Carleton University. He sees a similar pattern now playing out in Canadian politics.

"What we're seeing is the centre is hollowed and what we're seeing is [an] increasingly more fragmented political landscape, where there is a place for you if you're a right-wing authoritarian," said Graves.

Graves has been asking the four parenting questions in polls in Canada and he is noticing that feelings on the authoritarian end of the scale have been morphing over the last two years of living during the pandemic.

Like the virus itself, "it seems that under a variety of pressures, this ordered populist outlook is also mutating," he said. Graves believes misinformation is playing a key role: "the individuals in this group exhibit almost zero trust for government, science, media."

"The space for thoughtful discussion is being hollowed out by social media forums that reward the loudest voice and the most extreme attitude," said Peter Gordon.

"All individuals have that potential to become stereotypical and to respond to the world in a stereotyped or rigid fashion and the ultimate warning of the book is that's what's going to destroy democracy."

Guests in this episode:

Stuart Jeffries is a journalist and the author of Grand Hotel Abyss: the Lives of the Frankfurt School.

Peter E. Gordon is the Amabel B. James Professor of History at Harvard University. He wrote the introduction to a new edition of The Authoritarian Personality, published in 2019, ahead of the study's 70th anniversary.

Kathy Kiloh is an associate professor at OCAD University in Toronto and co-founder of The Association for Adorno Studies.

Molly Worthen is associate professor in the history department at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Matthew MacWilliams is a scholar of American politics and political culture and the author of On Fascism: 12 Lessons From American History.

Jonathan Weiler is a professor of global studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the co-author of two books about political psychology and polarization in the United States, including Prius or Pick Up: How the Answers to Four Simple Questions Explain America's Great Divide.

Frank Graves is the president and founder of Ekos Research Associates and an adjunct professor in the Department of Sociology at Carleton University.

*This episode was produced by Kristin Nelson.