Walter Benjamin Introduction

Walter Benjamin (1892–1940) is kind of hard to avoid—no matter how hard you try. This guy is everywhere. Why? Because he wrote on just about everything. We'll let a professional book reviewer take the reins for a second and list some of Benjamin's fave things to write:

metaphysical treatises, literary-critical monographs, philosophical dialogues, media-theoretical essays, book reviews, travel pieces, drug memoirs, whimsical feuilletons, diaries and aphorisms, modernist miniatures, radio plays for children, reflections on law, technology, theology and the philosophy of history, analyses of authors, artists, schools and epochs (source)

But wait! There's more!

He also wrote about the pleasures of smoking hashish. Okay, now that's it.

Don't get us wrong: Benjamin did not practice random acts of criticism. As wide-ranging as his work was, he was always focused on a few main themes. Let's take a look:

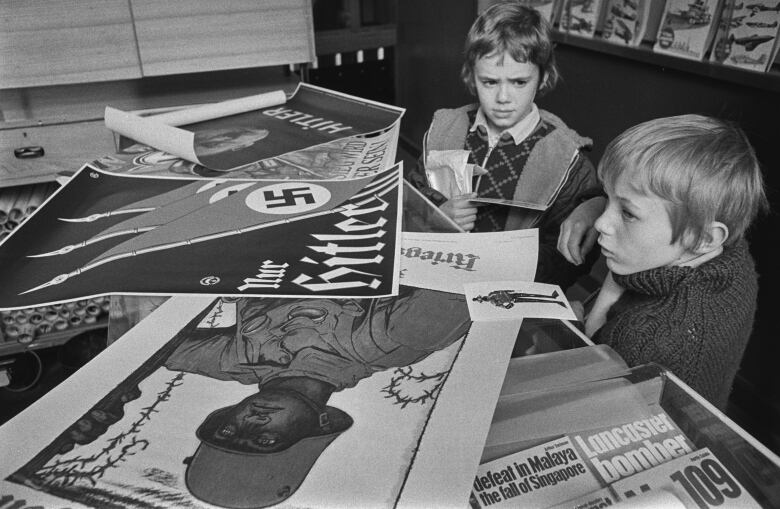

- He was a leftist critic of aesthetics. Translation: he hated Nazis, and he felt that art in the "age of mechanical reproduction" could be used for revolutionary purposes. Further translation: new photographic technology was going to help emancipate the people. That's what his uber-famous "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction" (1936) is all about. Well, that and a zillion other things.

- Benjamin was fascinated by history and didn't think it could be told as one linear, progressing narrative. To him, history was a collection of images and fragments, so that's how he wrote about it. (Speaking of which, Benjamin was all about writing in fragments—a sentence here, a sentence there. Get used to it.)

- He was captivated by Jewish history and Judaic ideas of Messianic time. Benjamin firmly believed that the Messiah would come and rescue humanity from Fascism and other ugly oppressions. Note: his version of the Messiah was not a long-haired, beatific-looking dude in flowing white robes. According to Benjamin, the Messiah coming to seek vengeance for all of those who had been subjugated was the people themselves. Deep.

- Benjamin loved him some Paris. The city, where he lived starting in 1933, was one of his biggest inspirations. He wrote a ton about malls (the 19th-century version), those iron-and-glass covered halls called "arcades." See: his ginormous and somehow unfinished book called The Arcades Project. He also wrote about French poets like Baudelaire, Parisian street life, and flâneurs, the 19th-century version of the mall crawler/people watcher.

ARTICLE

"Even the Dead Won't Be Safe": Walter Benjamin's Final Journey

In late September 1940, the German-Jewish intellectual, Walter Benjamin, embarked on a dangerous and ultimately ill-fated journey across the Pyrenees to escape the Nazis.

September 30, 2020

Top Image: Walter Benjamin, 1927. Image by Germaine Krull.

As German columns rolled across the border with the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg on May 10, 1940, 14 year old Arno Mayer climbed into a two-door Chevrolet with his parents, his sister, and his grandfather. A middle-class Jewish family, the Mayers had no illusions about what Nazi Germany’s invasion meant for them. They stayed ahead of the Wehrmacht and successfully avoided German aircraft, making it to France. After moving from town to town, they left France via Marseilles and arrived in Algeria. The following month, Arno’s father obtained American immigration visas in Casablanca, Morocco, in a manner strikingly similar to the plot of the classic film with Humphrey Bogart. In late winter of 1941, the family sailed, separately, from Portugal, setting foot in New York City four weeks apart. They survived. Resisting pressure to evacuate Luxembourg, Mayer's maternal grandparents fared far worse. Both were later deported to Theresienstadt, where his grandfather perished in December 1943. One of the lucky ones, Arno Mayer, who later became a leading historian of modern Europe, coined the term "Judeocide" in the 1980s to comprehend as best as humanly possible the annihilation of millions of Jews like his grandfather.

Hundreds of thousands of Jews in Western Europe were not nearly so fortunate. Among them was the German-Jewish intellectual, Walter Benjamin, in exile in France since 1933. Conventional routes of escape closed quickly as Nazi Germany occupied much of France and all of the Low Countries. To slip the Gestapo’s nets, Benjamin had to improvise. Four months after the German invasion, he embarked on a dangerous and ultimately ill-fated journey across the Pyrenees.

Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) was one of the seminal critics of modern cultural life (literature, theater, philosophy, theology, the study of language, the metropolis and its temptations and perils, painting, architecture, photography, radio, and the motion picture). While it is disgraceful that he was never offered an academic position, typical scholarly boundaries and territorialism could not contain him. Benjamin’s intellect was prodigious, restless, and nomadic.

Some of the most important Central European intellectuals of the twentieth century befriended Benjamin and attested to his brilliance.

“Everything which fell under the scrutiny of his words,” contended Theodor W. Adorno, “was transformed, as though it had become radioactive.

"His capacity for continually bringing out new aspects, not by exploding conventions through criticism, but rather by organizing himself so as to be able to relate to his subject-matter in a way that seemed beyond all convention—this capacity can hardly be adequately described by the concept of ‘originality.’” Hannah Arendt, with whom Benjamin became close in Paris during the 1930s, cautioned that “to describe adequately his work and him as an author within our usual framework of reference, one would have to make a great many negative statements,” in other words, spend an inordinate amount of time clarifying what Benjamin was not.

Gershom Scholem, the great scholar of Kabbalah and Jewish mysticism, recalled of Benjamin the “immediate impression of genius: the lucidity that often emerged from his obscure thinking; the vigor and acuity with which he experimented in conversation; and the unexpectedly serious manner, spiced with witty formulations; in which he would consider the things that were seething within me.” His distant cousin, Günther Stern, later to gain renown under the pseudonym Günther Anders for his works on technology and the atomic bomb, said of Benjamin, “next to him we are all unsubtle barbarians.” None of these recollections exaggerate.

Returning to his writings and his life, particularly, the awful end he met, I reflect on how fortunate I was to study Benjamin and his friend and interlocutor, Siegfried Kracauer, at the University of Chicago with Miriam Bratu Hansen in 1996-1997. Hansen, whose mother, Ruth Bratu, escaped from Czechoslovakia in a Kindertransport in 1939, had studied with Adorno at the University of Frankfurt. Her essays on Benjamin, mass media, and mass culture, commencing with the 1987 “Benjamin, Cinema, Experience,” set the standard for scholarship in English on these subjects. After I finished my master’s work with her, I still eagerly sought out every new article she published on Benjamin, Kracauer, or Adorno. Miriam struggled with cancer for 13 years before passing away at the far too young age of 61 in 2011. This article on the last years of Benjamin’s life is dedicated to her.