By Loz Blain

April 11, 2022

Over a 100-year time period, a tonne of hydrogen in the atmosphere will warm the Earth some 11 times more than a tonne of CO2, with an uncertainty of ± 5

Hydrogen will be one of humanity's key weapons in the war against carbon dioxide emissions, but it must be treated with care. New reports show how fugitive hydrogen emissions can indirectly produce warming effects 11 times worse than those of CO2.

Hydrogen can be used as a clean energy carrier, and running it through a fuel cell to produce electricity produces nothing but water as a by-product. It carries far more energy for a given weight than lithium batteries, and it's faster to refill a tank than to charge a battery, so hydrogen is viewed as a very promising green option in several hard-to-decarbonize applications where batteries won't cut the mustard – for example, aviation, shipping and long-haul trucking.

But when it's released directly into the atmosphere, hydrogen itself can interact with other gases and vapors in the air to produce powerful warming effects. Indeed, a new UK Government study has put these interactions under the microscope and determined that hydrogen's Global Warming Potential (GWP) is about twice as bad as previously understood; over a 100-year time period, a tonne of hydrogen in the atmosphere will warm the Earth some 11 times more than a tonne of CO2, with an uncertainty of ± 5.

How does hydrogen act like a greenhouse gas?

One way is by extending the lifetime of atmospheric methane. Hydrogen reacts with the same tropospheric oxidants that "clean up" methane emissions. Methane is an incredibly potent greenhouse gas, causing some 80 times more warming than an equivalent weight of CO2 over the first 20 years. But hydroxyl radicals in the atmosphere clean it up relatively quickly, while CO2 remains in the air for thousands of years, so CO2 is worse in the long run.

When hydrogen is present, however, those hydroxyl radicals react with the hydrogen instead. There are fewer cleanup agents to go around, so there's a direct rise in methane concentrations, and the methane stays in the atmosphere longer.

What's more, the presence of hydrogen increases the concentration of both tropospheric ozone and stratospheric water vapor, boosting a "radiative forcing" effect that also pushes temperatures higher.

How does hydrogen escape into the atmosphere?

A lot of it is leakage, according to a second report from Frazer-Nash Consultancy. Store hydrogen in a compressed gas cylinder, and you can assume you'll lose between 0.12 percent and 0.24 percent of it every day. It'll leak out of pipes and valves if you distribute it that way, losing some 20 percent more volume than the methane gas that's now running through municipal pipelines – although since hydrogen is so much lighter than methane, this larger volume equates to just 15 percent of the weight.

Where hydrogen is transported as a cryogenic liquid, boil-off is unavoidable, and you can expect to lose an average of about 1 percent of it per day. Currently, this is vented to the atmosphere.

Indeed, venting and purging operations are currently common across the hydrogen life cycle. They occur during electrolysis, during compression, during refueling, and during the process of conversion back into electricity through a fuel cell.

Where there is venting or purging, the percentages tend to dwarf what's lost through simple leakage – for example, current electrolysis procedures using venting and purging are assumed to lose between 3.3-9.2 percent of all hydrogen produced, depending largely on how often the process starts up and shuts down – this is a bit of a worry in situations where hydrogen production is seen as a way to store excess renewable energy that's not being snapped up by immediate demand.

Purging and venting emissions can be cleaned up significantly by adding systems to recombine the vented or purged hydrogen back into water and feed it back into the process – but it'll be a while before these kinds of operations are economically viable.

In all, the Frazer-Nash report expects that between 1-1.5 percent of all hydrogen in its central modeling scenario will be emitted into the atmosphere, with transport emissions responsible for around half of that, and emissions at the production and consumption ends taking up roughly a quarter each.

Meanwhile, operating under different assumptions, the first report linked expects somewhere between 1 percent and 10 percent of all hydrogen in its global scenario will be emitted into the atmosphere,

Does this mean "green hydrogen" should be avoided in the race to zero emissions?

No. The UK Government report explains that "the increase in equivalent CO2 emissions based on 1 percent and 10 percent H2 leakage rate offsets approximately 0.4 and 4 percent of the total equivalent CO2 emission reductions respectively," so even assuming the worst leakage scenario, it's still an enormous improvement.

"Whilst the benefits from equivalent CO2 emission reductions significantly outweigh the disbenefits arising from H2 leakage," it continues, "they clearly demonstrate the importance of controlling H2 leakage within a hydrogen economy."

Source: Atmospheric Implications of Increased Hydrogen Use/Fugitive Hydrogen Emissions in a Future Hydrogen Economy via Recharge News

BY SUMIT SINGH

Aviation accounts for 2.1% of global carbon emissions. While this figure seems low, the actual impact is significant. Moreover, the industry’s share could increase if there isn’t an overhaul. As a result, major players are touting the deployment of hydrogen fuel.

Getting the ball rolling

CFM International is a 50/50 joint venture between GE Aviation and Safran Aircraft Engines. The company is behind some of the most popular engines on the market, including the CFM56 and LEAP. Everyday jets from the Airbus A320neo and Boeing 737 MAX deploy the company's current-generation engines for their proven efficiency.

In February, CFM proudly announced that it is partnering with Airbus to pioneer hydrogen combustion technology. Notably, the project will play a significant role in the fruition of the ZEROe program, which Airbus touts will see the introduction of the world's first zero-emission commercial aircraft by 2035.

In practice, CFM will “modify the combustor, fuel system, and control system” of a GE PassportTM turbofan to perform on hydrogen. The engine was chosen because of its size, fuel flow ability, and modern turbo technology.

The product will be fitted along the rear fuselage of the testbed to allow engine emissions. Factors such as contrails will be analyzed separately from those of the engines powering the plane. The company will conduct a robust ground test program before the A380 flight test

Using its expertise

Even though these initiatives seem ambitious, CFM is confident in its approach. Its leadership highlights that it has proven time again that such tasks can be achieved.

Across the board, CFM’s RISE program seeks to reduce emissions by over 20% compared to today’s engines. The program is looking at open fan architecture and hybrid electric ability. It is looking at alternative sources, including hydrogen. It is also looking at 100% sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), something an Airbus A380 already flew with last week.

CFM International president and CEO Gaël Méheust shared the following at the Sustainable Skies World Summit 2022 in Farnborough, England, which Simple Flying attended:

“We’ve already gone through a similar journey. If you go back to the 1960s, with the growth of commercial aviation, and you look at where we are today, what is expected of us is the same thing that we’ve done in the past. The challenge is that we have to do it twice as fast.”

A balanced approach

All in all, CFM is taking a holistic approach to address sustainability concerns. The firm is designing technology for “ultra-efficient aircraft” to deliver 30% better efficiency to disrupt today’s short and medium-haul market. It is also adapting to different energy sources, with a phased transition timeline that will include different fuel types.

Nonetheless, the ultimate goal for a truly sustainable industry is a hydrogen-based offering. The technology involved in this scene is still maturing, but significant progress has already been made with the likes of ZeroAvia proving the possibility of modern hydrogen flight.

Méheust emphasizes that hydrogen is the true zero-carbon fuel. There is no carbon released with its combustion, and it’s as safe as Jet-A. However, there are considerable difficulties to be addressed, including storage and production tasks. Additionally, it’s currently more expensive than Jet-A. However, CFM concludes that in the bid to meet net-zero targets by 2050, these challenges will be taken on, and the industry will be able to adapt to a new ecosystem.

What are your thoughts about the future of hydrogen aviation? How do you feel the technology involved with the element will perform in the next chapter of aviation? Let us know what you think in the comment section.

About The Author

Sumit Singh

Deputy Editor - Sumit comes to Simple Flying with more than eight years’ experience as a professional journalist. Having written for The Independent, Evening Standard, and others, his role here allows him to explore his enthusiasm for aviation and travel. Having built strong relationships with Qatar Airways, United Airlines, Aeroflot, and more, Sumit excels in both aviation history and market analysis. Based in London, UK.More From Sumit Singh

Under pressure to cut emissions, truck manufacturers are choosing between batteries and hydrogen fuel cells. Wagering incorrectly could cost them billions of dollars.

The charging port for Navistar’s International Electric MV battery-powered truck, left, and Mercedes-Benz’s GenH2 truck, which is powered by hydrogen fuel cells

By Jack Ewing

April 11, 2022

Even before war in Ukraine sent fuel prices through the roof, the trucking industry was under intense pressure to kick its addiction to diesel, a major contributor to climate change and urban air pollution. But it still has to figure out which technology will best do the job.

Truck makers are divided into two camps. One faction, which includes Traton, Volkswagen’s truck unit, is betting on batteries because they are widely regarded as the most efficient option. The other camp, which includes Daimler Truck and Volvo, the two largest truck manufacturers, argues that fuel cells that convert hydrogen into electricity — emitting only water vapor — make more sense because they would allow long-haul trucks to be refueled quickly.

The choice companies make could be hugely consequential, helping to determine who dominates trucking in the electric vehicle age and who ends up wasting billions of dollars on the Betamax equivalent of electric truck technology, committing a potentially fatal error. It takes years to design and produce new trucks, so companies will be locked into the decisions they make now for a decade or more.

“It’s obviously one of the most important technology decisions we have to make,” said Andreas Gorbach, a member of the management board of Daimler Truck, which owns Freightliner in the United States and is the largest truck maker in the world.

The stakes for the environment and for public health are also high. If many truck makers wager incorrectly, it could take much longer to clean up trucking than scientists say we have to limit the worst effects of climate change. In the United States, medium- and heavy-duty trucks account for 7 percent of greenhouse gas emissions. Trucks tend to spend much more time on the road than passenger cars. The war in Ukraine has added urgency to the debate, underlining the financial and geopolitical risks of fossil fuel dependence.

While sales of electric cars are exploding, large truck makers have only begun to mass-produce emission-free vehicles. Daimler Truck, for example, began producing an electric version of its heavy duty Actros truck, with a maximum range of 240 miles, late last year. Tesla unveiled a design for a battery-powered semi truck in 2017, but has not set a firm production date.

Cost will be a decisive factor. Unlike car buyers, who might splurge on a vehicle because they like the way it looks or the status it conveys, truck buyers carefully calculate how much a rig is going to cost them to buy, maintain and refuel.

Battery-powered trucks sell for about three times as much as equivalent diesel models, although owners may recoup much of the cost in fuel savings. Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles will probably be even more expensive, perhaps one-third more than battery-powered models, according to auto experts. But the savings in fuel and maintenance could make them cheaper to own than diesel trucks as early as 2027, according to Daimler Truck.

“The environmental side is hugely important but if it doesn’t make financial sense, nobody’s going to do it,” said Paul Gioupis, chief executive of Zeem, a company that is building one of the largest electric vehicle charging depots in the country about one and a half miles from Los Angeles International Airport. Zeem will recharge trucks and service and clean them for clients like hotels, tour operators and delivery companies.

Proponents of hydrogen trucks argue that their preferred semis will refuel as fast as conventional diesel rigs and will also weigh less. Fuel cell systems are lighter than batteries, an important consideration for trucking companies seeking to maximize payload. Fuel cells tend to require fewer raw materials like lithium, nickel or cobalt that have been rising in price. (They do, however, require platinum, which soared in price after Russia invaded Ukraine. Russia is a major supplier.)

A new truck costs $140,000 or more. Owners anxious to clock as many cargo-hauling miles as possible won’t want their drivers to spend hours recharging batteries, Mr. Gorbach of Daimler said. “The longer the range, the higher the load, the better it is for hydrogen,” he said.

But other truck makers argue that batteries are much more efficient, and getting better all the time. They point out that it takes prodigious amounts of energy to extract hydrogen from water. Instead of using electricity to make hydrogen, battery proponents say, why not just let the energy directly power the truck’s motors?

Navistar’s electric long-haul truck. While sales of electric cars are exploding, large truck makers have only begun to mass-produce emission-free vehicles.

That argument will become stronger as technical advances allow manufacturers to produce batteries that can store more energy per pound and that can recharge in minutes, rather than hours. A long-haul truck that can recharge in half an hour is a few years away, said Andreas Kammel, who is in charge of electrification strategy at Traton, whose truck brands include Scania, MAN and Navistar.

“The cost advantage is here to stay and it’s significant,” Mr. Kammel said.

The hydrogen camp acknowledges that batteries are more efficient. All the major truck manufacturers plan to use batteries in smaller trucks, or trucks that travel shorter distances. The debate is about what makes the most sense for long-haul trucks traveling more than 200 miles a day, the kind that carry heavy loads across the breadth of the United States, Europe or China.

Most countries will struggle to produce enough electricity to drive fleets of battery-powered trucks, Daimler and Volvo executives say, arguing that hydrogen is a potentially unlimited source of energy. They envision a world in which countries that have a lot of sunlight, like Morocco or Australia, use solar energy to produce hydrogen that they send by ship or pipeline to the rest of the world.

Gerrit Marx, the chief executive of IVECO, a truck maker based in Italy, noted that Milan suffers power outages in summer when people run their air-conditioners. Just imagine, he said, what will happen when people start plugging in electric vehicles.

“If you have heavy duty trucks also on the grid for charging, it’s not going to work,” he said. IVECO is manufacturing trucks for Nikola, the troubled American start-up that plans to offer battery-powered and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles.

Hydrogen is also the only practical form of emission-free power for energy-hungry construction equipment or municipal vehicles like fire trucks, Mr. Marx said.

Much of the hydrogen produced today is extracted from natural gas, a process that generates more greenhouse gases than burning diesel. So-called green hydrogen produced with solar or water power is scarce and expensive. Hydrogen enthusiasts say the supply will expand quickly, and the price will come down, because of demand from steel, chemical and fertilizer producers who are also under pressure to reduce emissions. They will use hydrogen to run smelters and other industrial operations.

“Less than 10 percent of green hydrogen will be directed to road transport,” said Lars Stenqvist, a member of the executive board of Volvo who is responsible for technology. “We will sort of piggyback on the demand and infrastructure from other industries.”

Hydrogen has support from a formidable alliance of large corporations called H2Accelerate that includes the truck makers Daimler, Volvo and IVECO; the energy companies Royal Dutch Shell, OMV of Austria and TotalEnergies of France; and Linde, a German producer of industrial gas. Daimler and Volvo, normally intense rivals, have teamed up to develop fuel cells that convert hydrogen to electricity.

Proponents of hydrogen trucks argue that their preferred semis will refuel as fast as conventional diesel rigs and will also weigh less.

Hydrogen boosters have been wrong before. In the 1990s and early 2000s, Daimler and Toyota invested heavily to develop passenger cars that would run on hydrogen fuel cells. But the price of batteries fell and their performance improved faster than that of hydrogen cars. (Daimler Truck and the Mercedes-Benz car division have since split into separate companies. The car division is no longer selling hydrogen vehicles.)

To be sure, battery-powered trucks will also require major investment in high-voltage charging stations and other infrastructure. But building a charging network is likely to be much less expensive than establishing a green hydrogen industry along with the pipelines and tankers needed to transport the gas.

Fears that the electrical grid can’t handle a fleet of battery-powered trucks are overblown, Mr. Kammel of Traton said. Long-haul trucks will tend to charge at night when demand from other energy users is low, he said. In the United States, he said, big trucks spend a lot of time in Midwestern and Western states with plenty of wind and solar energy.

Whoever is right, battery-powered trucks will hit the road first. Daimler doesn’t plan to begin mass-producing a hydrogen fuel cell truck until after 2025, and in the meantime is planning to offer battery power as an option for smaller trucks, or large trucks that travel limited distances. Volvo and IVECO are pursuing similar strategies.

The big risk for those companies is that the affordability and performance of batteries, which have already exceeded expectations, could make hydrogen trucks obsolete before they get to market.

“The convenience disadvantages keep melting away,” Mr. Kammel said of battery power, “and the cost advantages keep growing.”

Jack Ewing writes about business from New York, focusing on the auto industry and the transition to electric cars. He spent much of his career in Europe and is the author of “Faster, Higher, Farther," about the Volkswagen emissions scandal. @JackEwingNYT • Facebook

Clean TrucksDebating how to get there

A Critical Year for Electric VehiclesThe popularity of battery-powered cars is soaring worldwide, even as the overall auto market stagnates.Going Mainstream: In December, Europeans for the first time bought more electric cars than diesels, once the most popular option.Turning Point: Electric vehicles account for a small slice of the market, but in 2022, their march could become unstoppable. Here is why.Tesla’s Success: A superior command of technology and its own supply chain allowed the company to bypass an industrywide crisis.Rivian’s Troubles: As the electric vehicle maker pares down its delivery targets for 2022, investors worry the company may not live up to its promise.Green Fleet: Amazon wants electric vans to make its deliveries. The problem? The auto industry barely produces any of the vehicles yet.

All 193 UN nations sign off on document that casts doubt on widespread use of H2 for heating and cars, while pointing out the many challenges the sector must overcome

Potential uses of hydrogen and H2 derivatives.

If the world is to reach net-zero emissions, hydrogen will play a vital role, according to the landmark Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Mitigation of Climate Change report, which was signed off by all 193 governments at the UN earlier this week.

The enormous document, drafted by 83 scientists from around the world, essentially sets out a broad roadmap on how the world can decarbonise, with much of the attention from the global media focused on the report’s views on fossil fuels, direct-air carbon capture (DACC) and the need to peak emissions by 2050.

'Now or never' | UN climate experts say emissions must peak by 2025 to stave off catastropheRead more

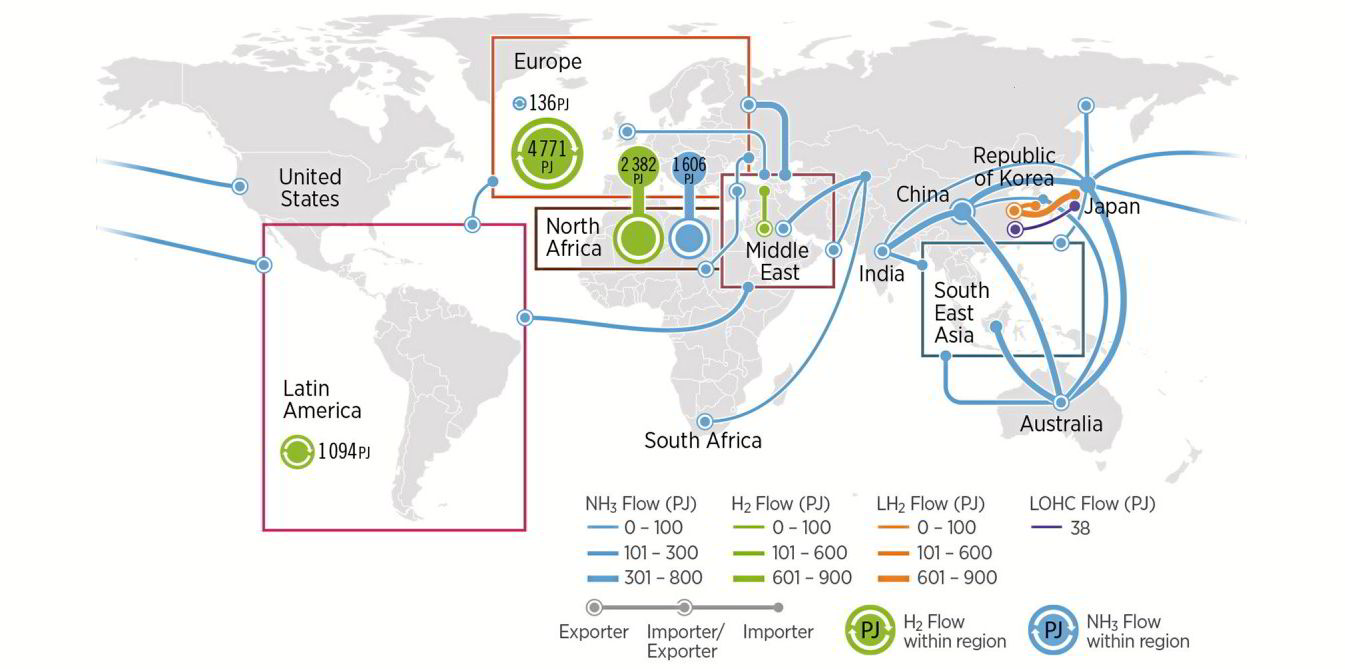

This is what the massive international clean hydrogen trade may look like in 2050: IrenaRead more

But within its 2,913 pages, the IPCC also explains how the world should use clean hydrogen — and the roles it should play in heating, transport, heavy industry and energy storage — as well as the significant challenges facing its production and use.

And its views may disappoint those bullish hydrogen advocates who believe H2 is needed in sectors such as heating and cars.

While it explains that H2 could theoretically be used for electricity generation, heat, transport, heavy industry and energy storage, it states that “future energy systems would not use hydrogen for all end uses”.

“They would use hydrogen to complement other energy carriers, mainly electricity, where hydrogen might have advantages.

“Hydrogen could provide long-term electricity storage to support high-penetration of intermittent renewables and could enable trading and storage of electricity between different regions to overcome seasonal or production capability differences.

“It could also be used in lieu of natural gas for peaking generation, provide process heat for industrial needs, or be used in the metal sector via direct reduction of iron ore. Clean hydrogen could be used as a feedstock in the production of various chemicals and synthetic hydrocarbons.

“Finally, hydrogen-based fuel cells could power vehicles. Recent advances in battery storage make electric vehicles the most attractive alternative for light-duty transport [ie, cars and vans]. However, fuel cell technology could complement electric vehicles in supporting the decarbonisation of heavy-duty transport segments (e.g., trucks, buses, ships, and trains).”

Products derived from clean hydrogen, such as ammonia and synthetic fuels, would probably also be needed to decarbonise shipping and aviation, it adds.

Heating

Many Western natural-gas companies, particularly distributors, are trying to argue that clean hydrogen will be pumped around existing gas grids and used to heat people’s homes, in the same way that gas boilers do today. But the IPCC is lukewarm on the idea.

“Electrification is is expected to be the dominant strategy in buildings as electricity is increasingly used for heating and for cooking,” it explains.

“Heat pumps are increasingly used in buildings and industry for heating and cooling. The ease of switching to electricity means that hydrogen is not expected to be a dominant pathway for buildings.

“Using electricity directly for heating, cooling and other building energy demand is more efficient than using hydrogen as a fuel, for example, in boilers or fuel cells. In addition, electricity distribution is already well developed in many regions compared to essentially non-existent hydrogen infrastructure, except for a few chemicals industry pipelines.”

Later on in the document, it says that while “converting gas grids to hydrogen might be an appealing option to decarbonise heat without putting additional stress on the electricity grids... the delivered cost of heat from hydrogen would be much higher than the cost of delivering heat from heat pumps, which could also be used for cooling”.

“Repurposing gas grids for pure hydrogen networks will also require system modifications such as replacement of piping and replacement of gas boilers and cooking appliances, a factor cost to be considered when developing hydrogen roadmaps for buildings.

“There are also safety and performance concerns with domestic hydrogen appliances. Over the period 1990-2019, hydrogen was not used in the building sector and scenarios assessed show a very modest role for hydrogen in buildings by 2050.”

Land transport

The IPCC says that “batteries are currently a more attractive option that hydrogen and fuel cells for light-duty vehicles” and that H2 represents “the most expensive option for LDV [light-duty vehicles], mainly due to the currently higher purchase price of the vehicle itself”.

And while it adds that fuel cells could be become a viable technology for cars and vans in the coming years, “the issues regarging the extra energy involved in creating the hydrogen and its delivery to refuelling sites remain, however”.

The case for hydrogen trucks | Grid limitations will make long-distance battery-electric haulage 'near impossible': Hyzon Motors CEO

‘Hydrogen unlikely to play major role in road transport, even for heavy trucks’: Fraunhofer

“The levelized cost of hydrogen on a GJ [gigajoule] basis is lower than conventional fossil fuels, but higher than electricity.”

The report seems slightly keener on the use of hydrogen in trucking and rail, but is hardly bullish, pointing to cost and production challenges.

“In general terms, electrification tends to play the key role in land-based transport,” the study says, but adds: “Land-based, long-range, heavy-duty trucks can be decarbonised through battery-electric haulage (including the use of electric road systems), complemented by hydrogen- and biofuel-based fuels in some contexts.

“These same technologies and expanded use of available electric rail systems can support rail decarbonisation (medium confidence).”

But it states: “These technologies nevertheless face challenges regarding driving range, capital and operating costs, and infrastructure availability. In particular, fuel cell durability, high energy consumption, and costs continue to challenge the commercialisation of hydrogen-based fuel cell vehicles. Increased capacity for low-carbon hydrogen production would also be essential for hydrogen-based fuels to serve as an emissions reduction strategy (high confidence).

And the report later adds: “Improvements in fuel cell technologies are needed to make hydrogen-based transport economically viable.”

Shipping and aviation

The IPCC study — officially known as AR6 [Assessment Report Six] Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change — points out that electrification is not a viable solution for decarbonising long-distance shipping or aviation, which instead requires “high energy density, low carbon fuels” that have not yet reached commercial scale.

“Decarbonisation options for shipping and aviation still require R&D, though advanced biofuels, ammonia, and synthetic fuels [derived from hydrogen, such as methanol, methane and petroleum] are emerging as viable options (medium confidence),” it states, adding that electrification could only play a niche role in aviation and shipping for short trips.

A third of all flights could run on liquid green hydrogen by 2050, says international body

Shipping giant Maersk to become major green hydrogen consumer as it embraces methanol fuel

“Improvements to national and international governance structures would further enable the decarbonisation of shipping and aviation (medium confidence). Such improvements could include, for example, the implementation of stricter efficiency and carbon intensity standards for the sectors (medium confidence).”

Nevertheless, significant questions remain about the cost of cleaner shipping and aviation fuels, the report continues.

“It is not clear if and when the combined costs of obtaining necessary feedstocks and producing these fuels without fossil inputs will be less than continuing to use fossil fuels and managing the related carbon through, for example, CCS [carbon capture and storage] or CDR [carbon dioxide removal].”

Heavy industry

While many hydrogen advocates have argued that H2 will be needed to provide high-temperature heat for heavy industry, the IPCC does not seem to agree.

“Industrial process heat demand, ranging from below 100°C to above 1000°C, can be met through a wide range of electrically powered technologies instead of using fuels... The main use of hydrogen and hydrogen carriers in industry is expected to be as feedstock (eg, for ammonia and organic chemicals) rather than for energy as industrial electrification increases,” the report says.

But later in the study, it states that options for industrial heat also include hydrogen, biofuels and CCS.

“Electrification is emerging as a key mitigation option for industry (high confidence). Using electricity directly, or indirectly via hydrogen from electrolysis for high temperature and chemical feedstock requirements, offers many options to reduce emissions. It also can provide substantial grid balancing services, for example through electrolysis and storage of hydrogen for chemical process use or demand response.”

Interestingly, the report also suggests that industrial production might be relocated to places with strong solar and wind resources.

SPECIAL REPORT | Is hydrogen the best option to decarbonise heating and heavy industry?

Vattenfall-led hydrogen-fuelled green steel pilot lands $160m in EU grants

“The geographical distribution of renewable resources has implications for industry (medium confidence). The potential for zero emission electricity and low-cost hydrogen from electrolysis powered by solar and wind, or hydrogen from other very low emission sources, may reshape where currently energy and emissions intensive basic materials production is located, how value chains are organized, trade patterns, and what gets transported in international shipping.

“Regions with bountiful solar and wind resources, or low fugitive CH4 [methane] co-located with CCS geology, may become exporters of hydrogen or hydrogen carriers such as methanol and ammonia, or home to the production of iron and steel, organic platform chemicals, and other energy intensive basic materials.”

Energy storage

Hydrogen and its derivatives could be useful for seasonal electricity storage — ie, H2 can be produced in the summer, stored for months and then converted back into electricity for use in cold winter months — the IPCC states.

“Hydrogen may prove valuable to improve the resilience of electricity systems with high penetration of variable renewable electricity. Flexible hydrogen electrolysis, hydrogen power plants and long-duration hydrogen storage may all improve resilience,” the report explains.

It does, however, point out that a “significant amount” would be needed “due to the low roundtrip efficiency of converting electricity to fuel and back again”.

“Electricity-to-hydrogen-to-electricity round-trip efficiencies are projected to reach up to 50% by 2030,” the study says.

Challenges

The IPCC paper explains that while “low- or zero-carbon produced hydrogen...” — ie, green and blue H2 — “is likely to have a significant role in future energy systems, due to its wide-range of applications (high confidence)”, it is currently not cost-competitive for large-scale applications.

'From the North to steelworks' | RWE plans 1,500km hydrogen pipeline grid through Germany

The 1,600TWh challenge | The six key steps needed to wean Europe off Russian gas

“Key challenges for hydrogen are: (a) cost-effective low/zero carbon production, (b) delivery infrastructure cost, (c) land area (ie, ‘footprint’) requirements of hydrogen pipelines, compressor stations, and other infrastructure, (d) challenges in using existing pipeline infrastructure, (e) maintaining hydrogen purity, (e) minimizing hydrogen leakage, and (f) the cost and performance of end-uses. Furthermore, it is necessary to consider the public perception and social acceptance of hydrogen technologies and their related infrastructure requirements.”

Later in the report, it states: “The potential role of hydrogen in future energy systems depends on more than just production methods and costs. For some applications, the competitiveness of hydrogen also depends on the availability of the infrastructure needed to transport and deliver it at relevant scales.

“Transporting hydrogen through existing gas pipelines is generally not feasible without changes to the infrastructure itself. Existing physical barriers, such as steel embrittlement and degradation of seals, reinforcements in compressor stations, and valves, require retrofitting during the conversion to H2 distribution or new H2 dedicated pipelines to be constructed.”

It continues: “About three times as much compressed hydrogen by volume is required to supply the same amount of energy as natural gas. Security of supply is therefore more challenging in hydrogen networks than in natural gas networks.

“There are also safety concerns associated with the flammability and storage of hydrogen which will need to be considered.”

However, the report adds: “The capacity to leverage and convert existing gas infrastructure to transport hydrogen will vary regionally, but in many cases could be the most economically viable pathway.”

Electricity more efficient

The IPCC’s opinions on the use of hydrogen can be summed up in the following statement from the report:

“As a general rule, and across all sectors, it is more efficient to use electricity directly and avoid the progressively larger conversion losses from producing hydrogen, ammonia, or constructed [ie, synthetic] low GHG [greenhouse gas] hydrocarbons. What hydrogen does do, however, is add time and space option value to electricity produced using variable clean sources, for use as hydrogen, as stored future electricity via a fuel cell or turbine, or as an industrial feedstock.”

And it is worth pointing out that, of course, hydrogen will play a relatively small role in the overall race to net zero emissions.

“Net Zero energy systems will share common characteristics, but the approach in every country will depend on national circumstances,” the IPCC states.

“Common characteristics of net zero energy systems will include: (1) electricity systems that produce no net CO2 or remove CO2 from the atmosphere; (2) widespread electrification of end uses, including light-duty transport, space heating, and cooking; (3) substantially lower use of fossil fuels than today (4) use of alternative energy carriers such as hydrogen, bioenergy, and ammonia to substitute for fossil fuels in sectors less amenable to electrification; (5) more efficient use of energy than today; (6) greater energy system integration across regions and across components of the energy system; and (7) use of CO2 removal (e.g., DACCS, BECCS [bioenergy with carbon capture and storage]) to offset any residual emissions. (high confidence).”