Thu, April 21, 2022

HELENA, Mont. (AP) — For the past year a company that “mines” cryptocurrency had what seemed the ideal location for its thousands of power-thirsty computers working around the clock to verify bitcoin transactions: the grounds of a coal-fired power plant in rural Montana.

But with the cryptocurrency industry under increasing pressure to rein in the environmental impact of its massive electricity consumption, Marathon Digital Holdings made the decision to pack up its computers, called miners, and relocate them to a wind farm in Texas.

“For us, it just came down to the fact that we don’t want to be operating on fossil fuels,” said company CEO Fred Thiel.

In the world of bitcoin mining, access to cheap and reliable electricity is everything. But many economists and environmentalists have warned that as the still widely misunderstood digital currency grows in price — and with it popularity — the process of mining that is central to its existence and value is becoming increasingly energy intensive and potentially unsustainable.

Bitcoin was was created in 2009 as a new way of paying for things that would not be subject to central banks or government oversight. While it has yet to widely catch on as a method of payment, it has seen its popularity as a speculative investment surge despite volatility that can cause its price to swing wildly. In March 2020, one bitcoin was worth just over $5,000. That surged to a record of more than $67,000 in November 2021 before falling to just over $35,000 in January.

Central to bitcoin's technology is the process through which transactions are verified and then recorded on what's known as the blockchain. Computers connected to the bitcoin network race to solve complex mathematical calculations that verify the transactions, with the winner earning newly minted bitcoins as a reward. Currently, when a machine solves the puzzle, its owner is rewarded with 6.25 bitcoins — worth about $260,000 total. The system is calibrated to release 6.25 bitcoins every 10 minutes.

When bitcoin was first invented it was possible to solve the puzzles using a regular home computer, but the technology was designed so problems become harder to solve as more miners work on them. Those mining today use specialized machines that have no monitors and look more like a high-tech fan than a traditional computer. The amount of energy used by computers to solve the puzzles grows as more computers join the effort and puzzles are made more difficult.

Marathon Digital, for example, currently has about 37,000 miners, but hopes to have 199,000 online by early next year, the company said.

Determining how much energy the industry uses is difficult because not all mining companies report their use and some operations are mobile, moving storage containers full of miners around the country chasing low-cost power.

The Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index estimates bitcoin mining used about 109 terrawatt hours of electricity over the past year — close to the amount used in Virginia in 2020, according to the U.S. Energy Information Center. The current usage rate would work out to 143 TWh over a full year, or about the amount used by Ohio or New York state in 2020.

Cambridge's estimate does not include energy used to mine other cryptocurrencies.

A key moment in the debate over bitcoin’s energy use came last spring, when just weeks after Tesla Motors said it was buying $1.5 billion in bitcoin and would also accept the digital currency as payment for electric vehicles, CEO Elon Musk joined critics in calling out the industry’s energy use and said the company would no longer be taking it as payment.

Some want the government to step in with regulation.

In New York, Gov. Kathy Hochul is being pressured to declare a moratorium on the so-called proof-of-work mining method — the one bitcoin uses — and to deny an air quality permit for a project at a retrofitted coal-fired power plant that runs on natural gas.

A New York State judge recently ruled the project would not impact the air or water of nearby Seneca Lake.

“Repowering or expanding coal and gas plants to make fake money in the middle of a climate crisis is literally insane,” Yvonne Taylor, vice president of Seneca Lake Guardians, said in a statement.

Anne Hedges with the Montana Environmental Information Center said that before Marathon Digital showed up, environmental groups had expected the coal-fired power plant in Hardin, Montana, to close.

“It was a death watch,” Hedges said. “We were getting their quarterly reports. We were looking at how much they were operating. We were seeing it continue to decline year after year — and last year that totally changed. It would have gone out of existence but for bitcoin.”

The cryptocurrency industry “needs to find a way to reduce its energy demand,” and needs to be regulated, Hedges said. “That’s all there is to it. This is unsustainable.”

Some say the solution is to switch from proof-of-work verification to proof-of-stake verification, which is already used by some cryptocurrencies. With proof of stake, verification of digital currency transfers is assigned to computers, rather than having them compete. People or groups that stake more of their cryptocurrency are more likely to get the work — and the reward.

While the method uses far less electricity, some critics argue proof-of-stake blockchains are less secure.

Some companies in the industry acknowledge there is a problem and are committing to achieving net-zero emissions — adding no greenhouse gases to the atmosphere — from the electricity they use by 2030 by signing onto a Crypto Climate Accord, modeled after the Paris Climate Agreement.

“All crypto communities should work together, with urgency, to ensure crypto does not further exacerbate global warming, but instead becomes a net positive contributor to the vital transition to a low carbon global economy,” the accord states.

Marathon Digital is one of several companies pinning its hopes on tapping into excess renewable energy from solar and wind farms in Texas. Earlier this month the companies Blockstream Mining and Block, formerly Square, announced they were breaking ground in Texas on a small, off-the-grid mining facility using Tesla solar panels and batteries.

“This is a step to proving our thesis that bitcoin mining can fund zero-emission power infrastructure," said Adam Back, CEO and co-founder of Blockstream.

Companies argue that cryptocurrency mining can provide an economic incentive to build more renewable energy projects and help stabilize power grids. Miners give renewable energy generators a guaranteed customer, making it easier for the projects to get financing and generate power at their full capacity.

The mining companies are able to contract for lower-priced energy because “all the energy they use can be shut off and given back to the grid at a moment’s notice,” said Thiel.

In Pennsylvania, Stronghold Digital is cleaning up hundreds of years of coal waste by burning it to create what the state classifies as renewable energy that can be sent to the grid or used in bitcoin mining, depending on power demands.

Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection is a partner in the work, which uses relatively new technology to burn the waste coal more efficiently and with fewer emissions. Left alone, piles of waste coal can catch fire and burn for years, releasing greenhouse gases. When wet, the waste coal leaches acid into area waterways.

After using the coal waste to generate electricity, what’s left is “toxicity-free fly ash,” which is registered by the state as a clean fertilizer, Stronghold Digital spokesperson Naomi Harrington said.

As Marathon Digital gradually moves its 30,000 miners out of Montana, it's leaving behind tens of millions of dollars in mining infrastructure behind.

Just because Marathon doesn’t want to use coal-fired power anymore doesn’t mean there won’t be another bitcoin miner to take its place. Thiel said he assumes the power plant owners will find a company to do just that.

“No reason not to,” he said.

Amy Beth Hanson, The Associated Press

Going green: How to ditch fossil fuels powering the bitcoin network

The amount of energy used by computers to solve the puzzles grows as more computers join the effort and puzzles are made more difficult

AP | Helena (US) Last Updated at April 21, 2022

For the past year a company that mines cryptocurrency had what seemed the ideal location for its thousands of power-thirsty computers working around the clock to verify bitcoin transactions: the grounds of a coal-fired power plant in rural Montana.

But with the cryptocurrency industry under increasing pressure to rein in the environmental impact of its massive electricity consumption, Marathon Digital Holdings made the decision to pack up its computers, called miners, and relocate them to a wind farm in Texas.

For us, it just came down to the fact that we don't want to be operating on fossil fuels, said company CEO Fred Thiel.

In the world of bitcoin mining, access to cheap and reliable electricity is everything.

But many economists and environmentalists have warned that as the still widely misunderstood digital currency grows in price and with it popularity the process of mining that is central to its existence and value is becoming increasingly energy intensive and potentially unsustainable.

Bitcoin was was created in 2009 as a new way of paying for things that would not be subject to central banks or government oversight.

While it has yet to widely catch on as a method of payment, it has seen its popularity as a speculative investment surge despite volatility that can cause its price to swing wildly.

In March 2020, one bitcoin was worth just over USD 5,000. That surged to a record of more than USD 67,000 in November 2021 before falling to just over USD 35,000 in January.

Central to bitcoin's technology is the process through which transactions are verified and then recorded on what's known as the blockchain.

Computers connected to the bitcoin network race to solve complex mathematical calculations that verify the transactions, with the winner earning newly minted bitcoins as a reward.

Currently, when a machine solves the puzzle, its owner is rewarded with 6.25 bitcoins worth about USD 260,000 total. The system is calibrated to release 6.25 bitcoins every 10 minutes.

When bitcoin was first invented it was possible to solve the puzzles using a regular home computer, but the technology was designed so problems become harder to solve as more miners work on them. Those mining today use specialised machines that have no monitors and look more like a high-tech fan than a traditional computer.

The amount of energy used by computers to solve the puzzles grows as more computers join the effort and puzzles are made more difficult.

Marathon Digital, for example, currently has about 37,000 miners, but hopes to have 199,000 online by early next year, the company said.

Determining how much energy the industry uses is difficult because not all mining companies report their use and some operations are mobile, moving storage containers full of miners around the country chasing low-cost power.

The Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index estimates bitcoin mining used about 109 terrawatt hours of electricity over the past year close to the amount used in Virginia in 2020, according to the US Energy Information Center.

The current usage rate would work out to 143 TWh over a full year, or about the amount used by Ohio or New York state in 2020.

Cambridge's estimate does not include energy used to mine other cryptocurrencies.

A key moment in the debate over bitcoin's energy use came last spring, when just weeks after Tesla Motors said it was buying USD 1.5 billion in bitcoin and would also accept the digital currency as payment for electric vehicles, CEO Elon Musk joined critics in calling out the industry's energy use and said the company would no longer be taking it as payment.

Some want the government to step in with regulation.

In New York, Gov. Kathy Hochul is being pressured to declare a moratorium on the so-called proof-of-work mining method the one bitcoin uses and to deny an air quality permit for a project at a retrofitted coal-fired power plant that runs on natural gas.

A New York State judge recently ruled the project would not impact the air or water of nearby Seneca Lake.

Repowering or expanding coal and gas plants to make fake money in the middle of a climate crisis is literally insane, Yvonne Taylor, vice president of Seneca Lake Guardians, said in a statement.

Anne Hedges with the Montana Environmental Information Center said that before Marathon Digital showed up, environmental groups had expected the coal-fired power plant in Hardin, Montana, to close.

It was a death watch, Hedges said.

We were getting their quarterly reports. We were looking at how much they were operating. We were seeing it continue to decline year after year and last year that totally changed. It would have gone out of existence but for bitcoin.

The cryptocurrency industry needs to find a way to reduce its energy demand, and needs to be regulated, Hedges said. That's all there is to it. This is unsustainable.

Some say the solution is to switch from proof-of-work verification to proof-of-stake verification, which is already used by some cryptocurrencies. With proof of stake, verification of digital currency transfers is assigned to computers, rather than having them compete.

People or groups that stake more of their cryptocurrency are more likely to get the work and the reward.

While the method uses far less electricity, some critics argue proof-of-stake blockchains are less secure.

Some companies in the industry acknowledge there is a problem and are committing to achieving net-zero emissions adding no greenhouse gases to the atmosphere from the electricity they use by 2030 by signing onto a Crypto Climate Accord, modeled after the Paris Climate Agreement.

All crypto communities should work together, with urgency, to ensure crypto does not further exacerbate global warming, but instead becomes a net positive contributor to the vital transition to a low carbon global economy, the accord states.

Marathon Digital is one of several companies pinning its hopes on tapping into excess renewable energy from solar and wind farms in Texas.

Earlier this month the companies Blockstream Mining and Block, formerly Square, announced they were breaking ground in Texas on a small, off-the-grid mining facility using Tesla solar panels and batteries.

This is a step to proving our thesis that bitcoin mining can fund zero-emission power infrastructure," said Adam Back, CEO and co-founder of Blockstream.

Companies argue that cryptocurrency mining can provide an economic incentive to build more renewable energy projects and help stabilize power grids.

Miners give renewable energy generators a guaranteed customer, making it easier for the projects to get financing and generate power at their full capacity.

The mining companies are able to contract for lower-priced energy because all the energy they use can be shut off and given back to the grid at a moment's notice, said Thiel.

In Pennsylvania, Stronghold Digital is cleaning up hundreds of years of coal waste by burning it to create what the state classifies as renewable energy that can be sent to the grid or used in bitcoin mining, depending on power demands.

Pennsylvania's Department of Environmental Protection is a partner in the work, which uses relatively new technology to burn the waste coal more efficiently and with fewer emissions.

Left alone, piles of waste coal can catch fire and burn for years, releasing greenhouse gases. When wet, the waste coal leaches acid into area waterways.

After using the coal waste to generate electricity, what's left is toxicity-free fly ash, which is registered by the state as a clean fertilizer, Stronghold Digital spokesperson Naomi Harrington said.

As Marathon Digital gradually moves its 30,000 miners out of Montana, it's leaving behind tens of millions of dollars in mining infrastructure behind.

Just because Marathon doesn't want to use coal-fired power anymore doesn't mean there won't be another bitcoin miner to take its place. Thiel said he assumes the power plant owners will find a company to do just that.

No reason not to, he said.

A Fossil Fuel Power Plant That Mines Bitcoin Is Fighting to Stay Open

Regulators say the Greenidge plant in New York State is fighting an an "uphill battle" to prove it's environmentally-friendly enough to stay open.

By Audrey Carleton

20.4.22

A natural gas-fired power plant connected to a Bitcoin mine in Dresden, New York is fighting to green its image as it vies for renewed permits from the state.

The Greenidge power plant has become the center of fierce debate over Bitcoin mining in New York State and how the industry fits into the state’s climate goals. Decommissioned as a coal-fired plant in 2011, Greenidge was reopened in 2017 after being purchased by Atlas Holdings and converted to a natural gas plant, spinning up Bitcoin mining starting in 2019. Today, it’s one of the largest Bitcoin mining facilities in the U.S., running 17,000 rigs.

Greenidge lauds itself as “carbon neutral,” claiming to offset the emissions that come from burning fossil fuels to generate bitcoins with “reliable, verified” credits and systems that it says are more efficient than the network standard. But that’s not enough for many environmentalist opponents, including Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), who say the environmental footprint of Bitcoin mining outweighs any justification for its existence, especially when it uses fossil fuels directly.

“Given the extraordinarily high energy usage and carbon emissions associated with Bitcoin mining, mining operations at Greenidge and other plants raise concerns about their impacts on the global environment, on local ecosystems, and on consumer electricity costs,” Warren wrote in a letter to the plant’s CEO, Jeffrey Kirt, last December.

Despite purchasing offsets, the plant’s emissions increased “nearly tenfold from 2019 to 2020,” Warren’s letter claims, citing data from the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) obtained by the Committee To Preserve The Finger Lakes, which opposes the Greenidge plant’s mining operation. In 2020, those emissions were comparable to that of 50,000 cars, the letter reads. At the time, Greenidge told Bloomberg that the operation “meets all of New York’s nation-leading environmental standards.”

Even so, the plant faces an “uphill battle,” for its permits, DEC Commissioner Basil Seggos told Binghamton, New York-based broadcaster WSKG on Monday, noting that he still has “significant concerns” about the environmental impact of its operations.

“DEC has advised the applicant, Greenidge Generation, LLC, of the need for additional greenhouse gas (GHG) mitigation measures to meet the requirements of the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act,” a warning on the DEC website reads. “On March 25, the applicant, Greenidge Generation, LLC, proposed GHG mitigation measures for the facility as part of the current Title V and IV permit renewal process. DEC has not made a determination regarding the sufficiency of the proposed GHG mitigation measures in meeting these requirements.”

“DEC subjects every application to all applicable federal and State standards to ensure the agency’s decision is protective of public health and the environment and upholds environmental justice and fairness,” the agency told Motherboard in an email.

The regulator is still “reviewing additional information submitted by” Greenidge, alongside some 4,000 public comments it received about the plant, the notice continues.

The agency’s hesitation primarily comes down to a piece of landmark climate legislation passed in 2019 that, at the time, positioned New York state as a national leader in environmental policy. The Climate and Community Leadership Protection Act (CLCPA) established a set of legally-binding environmental targets requiring 70 percent of New York’s energy to come from renewable sources by 2030 in order to reduce statewide greenhouse gas emissions by 85 percent by 2050. Now, three years after the Act’s passage, advocates say the state is far from achieving these goals. Allowing the proliferation of Bitcoin mining tied to fossil fuel plants would set New York even farther back from them, critics say, as it extends a lifeline to fossil fuel infrastructure that would otherwise have no reason to exist.

Greenidge underscored in its March 25 proposal to the DEC that it is “prepared do more than the legal minimum—and more that it has already done—to reduce [greenhouse gas] emissions in support of the Department’s effort to achieve CLCPA’s goals.” It proposed reducing its overall emissions volumes by 40 per cent from what’s currently permitted by the end of 2025, five years before the CLCPA’s 2030 renewable targets. The plant underscored that its own emissions comprise well under one percent of the state’s overall emissions and power volumes.

“The State of New York should lead, embracing the cryptocurrency industry and all the opportunity we’ve shown it can create for New Yorkers while complying with the nation’s most aggressive environmental standards and laws addressing climate change,” Greenidge said in a statement emailed to Motherboard. “We look forward to finalizing a strong, renewed [air] permit to allow Greenidge to continue its environmental and economic stewardship in New York.”

In addition to regulators’ concerns, local critics like Seneca Lake Guardian and Committee to Preserve the Finger Lakes oppose not just Greenidge’s atmospheric emissions, but its potential impact on water quality around the plant. Last year, a claim that the facility has turned the glacial lake it sits next to into a “hot tub” went viral. That claim wasn’t true, but shows the level of angst Greenidge has fomented in the region, and may have a kernel of truth to it. The facility’s intake pipe draws up fresh water from the nearby Seneca Lake to power the facility with steam and cool it, pumping it back out at an allowed maximum of 108 degrees. Greenridge maintains that in 2021 it never reached that temperature and the average discharge temperature is approximately 32 degrees below the permitted level.

That this type of setup can imperil local wildlife is a well-documented phenomenon. Intake pipes suck in water and wildlife indiscriminately, Grist reported in 2021. This can result in fish and wildlife being mangled by facilities, which the Sierra Club once described as “giant fish blenders.”

Many of these environmental groups hope to see the state issue a moratorium on the issuing of permits for Bitcoin mining as a whole: Citing the state’s move to ban fracking in 2014, advocates say the state has a well-defined legislative pathway to putting an end to Bitcoin mining. Most recently, that chorus of voices came to include New York City Public Advocate and gubernatorial candidate Jumaane Williams, who called on Governor Kathy Hochul to place a moratorium on Proof-of-Work mining. The technique for providing network security used by Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies involves brute-force number crunching in a global lottery to add a block of valid transactions to the chain. To Bitcoiners, this is a critical part of the system, but to critics, it’s a lot of wasted energy.

“Bitcoin mines that use a 'Proof-of-Work' process are known to cause significant damage to the environment and local economy, which is why many countries have completely banned the practice,” Williams told local broadcaster Spectrum News in February. “Unfortunately New York has fallen behind, allowing nearly 20 percent of the country's mines to operate in our state without any oversight or regulation. We need to ask questions now rather than dealing with the fallout later."

A bill that would put a two-year moratorium on all Proof-of-Work mining in New York has garnered traction in the state legislature—it would put an end to what The New York Times called a “Bitcoin boom” in Northern and Western New York. Bitcoin mining doesn’t need fossil fuels, and New York State is home to ample hydropower and shuttered industrial plants, making it a leading producer of new bitcoins nationwide as firms seek cheap power.

Still, many environmentalists fear that Greenidge’s case is part of a larger wave of once-mothballed power plants coming back to life via Bitcoin. There are an estimated 30 mothballed coal and oil-powered plants across the state that could be fodder for mining operations like this one, Buffalo News reported last July.

Greenidge, for its part, remains firm that it’s taken steps to meet the requirements the DEC has laid out for its permit approvals.

“We are willing to do far more than we have already done to further reduce [greenhouse gas] emissions and help the state achieve its statewide CLCPA goals,” the plant said in a statement on March 31. “Notwithstanding the noise from our few remaining opponents, this is a standard air permit renewal governing permitted emissions levels, not a cryptocurrency permit. Their efforts to mislead the public—and to cause our team members and IBEW [union] partners to lose their jobs without any basis in law or fact—have been shameful.”

After China banned Bitcoin, an exodus of mining computers made their way all over the globe.

By Melissa Chan

21.4.22

This article is based on reporting for the seventh episode of CRYPTOLAND, Motherboard’s documentary series about how cryptocurrency is affecting culture, politics, the environment, and our shared future. Watch it on Motherboard’s YouTube.

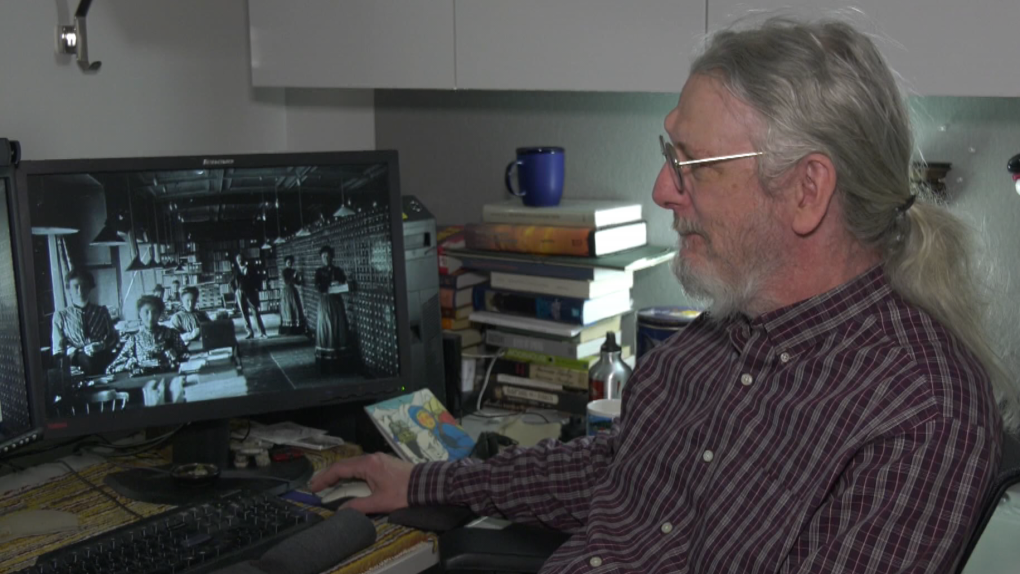

Outside a warehouse in upstate New York, Sam Tabar stands transfixed, gazing at a pile of coal as a Caterpillar excavator scoops chunks up for removal. His company, Bit Digital, is one of the world's largest cryptocurrency mining firms, and it has taken over this former coal plant for its own operations.

“It’s come full circle now,” he marvels. “We have these places that were devastated by China's takeover of manufacturing,” referring to American Rust Belt deindustrialization over the past few decades. But now, “the future is coming back to Buffalo, thanks to China.”

China once dominated the Bitcoin mining market, the computing process by which new Bitcoin enters circulation. The country once accounted for more than 80 percent of the world’s Bitcoin mining. But in the way authoritarian states can, Beijing decided to ban all foreign cryptocurrencies last year in part to bolster its own centrally-controlled digital yuan. As miners scrambled to move their valuable hardware out, they made bets on which countries were safest to install their machines. By geographic proximity and the promise of cheap energy, some transferred their assets to Russia and Kazakhstan. Others opted for higher transport fees and sent their equipment to the United States. Given Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Kazakhstan’s own violent political unrest this January, the choice has brought to sharp focus the mining risks in closed societies versus open societies.

Bit Digital had 30,000 ASICs—the machines used for mining—in China. Tabar, the company’s Chief Strategy Officer, and the rest of the team spent months shipping units, each worth thousands of dollars, out by plane, train, and boat. Choosing the United States made sense to Tabar.

“There's rule of law, there's transparency on decision making,” he says. The Biden administration’s March executive order on cryptocurrencies, though absent on specifics, indicates that the US views digital assets as important to maintaining American leadership in global finance. “I am hopeful that the FCC and other stakeholders [will] have a very thoughtful conversation about regulation and not stamp out innovation,” says Tabar.

Time was of the essence when companies were deciding where to relocate their machines. Every minute an ASIC is not plugged in is a minute it isn’t mining for potential Bitcoin. When miners look for efficiency, autocracies have their appeal. Leaders can make magic happen with a snap of their fingers. Kazakhstan saw an opportunity as mining units left China and its president, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, welcomed crypto cowboys to his frontier, promising minimal regulation and cheap electricity.

Kazakh startup Enegix quickly threw up data centers where incoming miners could pay to plug in their machines. In addition to low energy costs, Enegix CEO Yerbolsyn Sarsenov touted its northern operations in the near-Siberian cold as an asset, because Bitcoin mines generate a lot of heat, and keeping ASICs from overheating can be a challenge at certain mines. Enegix's facility is “dry and cool, so hardware has a long service life and stays operational for a long time,” he explains to Motherboard.

Short-term ease-of-setup in an authoritarian state, however, can translate to long-term uncertainty. Tokayev giveth, and he taketh away. A few months after the leader’s crypto pronouncement, the government unexpectedly limited the amount of power prospectors could tap into, saying it would be rolled back by up to 95 percent. Mining activity crashed overnight. As the future of mining in the country suddenly looked dicey, problems deepened as nationwide anti-government protests prompted a bloody crackdown.

Following the unrest, Tokayev has devoted the past few months to consolidating power and putting pressure on the family and associates of Kazakhstan’s previous leader, Nursultan Nazarbayev, who ruled for almost three decades. Some of these curbs included stopping their Bitcoin ventures. Along with pursuing elites, officials also went after smaller mining operators, forcing many unlicensed ones to shutter.

Alex Gladstein, author of Check Your Financial Privilege: Inside the Global Bitcoin Revolution and Chief Strategy Officer at Human Rights Foundation, believes most miners exiting China “would’ve preferred to have rack space in Canada, Iceland, Norway, or the United States.” China’s Bitcoin ban had happened quickly, and many Western operators were unprepared to absorb the flood of hardware. Kazakhstan, he argues, was more of a backup option.

Cambridge University’s Center for Alternative Finance shows Kazakhstan grabbing second place after the US in global Bitcoin mining rankings, but most observers expect it to slip this year. It may still stick around as a significant player, however, given Russia’s new status as a pariah state and a potential exodus of Russian miners who would prefer to operate in a country free of sanctions. While the fall of the ruble has led to cheaper energy costs in Russia, miners there will soon face difficulties procuring hardware. Several firms have already pivoted from Russia to Kazakhstan. Enegix’s future success may partly depend on this second migration of ASICs.

The outcome for now however, puts the US firmly in the global lead, a warp speed transfer of wealth within one year from China — or a transfer of a boondoggle, depending on one’s assessment of cryptocurrencies. Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies remain a highly divisive and debated digital development, and US politicians have wrestled over whether to welcome the industry to their respective jurisdictions.

Here US federalism is an asset, allowing states and cities to explore different policies. Texas has leaned in hard, with Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX), himself a Bitcoin investor, pledging the state will "become the center of the universe for Bitcoin and crypto.” Elsewhere however, including in New York State and imperiling Bit Digital’s operations there, legislators have introduced a bill seeking to impose a two-year moratorium on cryptocurrency mining.

Gladstein believes that Bit Digital and other companies would simply move to other states. Ultimately, he believes mining activity will largely settle in democracies. “You’re probably going to see over the coming decade the majority of infrastructure inside countries that have stronger rule of law,” he says.

For miners who must contend with the wild fluctuations in the value of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, a reliable and stable business environment is most welcome.

April 20, 2022

By Peter Coy

Opinion Writer

You're reading Peter Coy's newsletter,. A veteran business and economics columnist unpacks the biggest headlines.

The people behind Bitcoin, the No. 1 cryptocurrency by market value (and renown), are under heavy pressure to reduce its carbon footprint — the planet-warming emissions from burning fossil fuels for electricity to run the network’s computations, known as mining. I spoke with people on both sides of the argument and came away thinking that Bitcoin is highly unlikely to change its fundamental way of operating.

Bitcoin feels wasteful to a lot of people because its security depends on buying lots of specialized computing hardware that’s useless for any other purpose and then running it hard, which consumes joules and joules of electricity. The Cambridge Center for Alternative Finance calculates that Bitcoin mining, on the whole, consumes slightly more energy than gold mining, which is a fair comparison, since both Bitcoin tokens and gold are pitched as alternatives to fiat currencies such as the U.S. dollar. Bitcoin mining consumes more electricity than Norway but slightly less than Egypt, the center says, and accounts for 0.62 percent of the world’s total electricity consumption.

Here is a mind-blowing stat about Bitcoin: Every second, the Bitcoin network performs about 200 quintillion hashes, which are essentially guesses about a certain very long string of digits. There’s a race among Bitcoin network participants, known as miners, to make guesses faster and faster so they can be first and win rewards in the form of Bitcoin. It’s cheaper for them than buying Bitcoin on the open market: The token’s price is up more than thirtyfold over the past five years.

As the miners get faster, the network automatically makes the problem they need to solve harder, essentially spinning the treadmill faster. The Bitcoin network was designed this way to limit the pace at which new blocks of verified data are formed to one every 10 minutes. Unlike with most other cryptocurrencies, there is a built-in ceiling on production of tokens. More than 90 percent of the 21 million Bitcoin that will ever exist have already been mined, making each one more valuable.

Pressure on Bitcoin to switch to a less energy-intensive approach is coming from several directions. Ethereum, the No. 2 cryptocurrency, is switching from proof of work, which Bitcoin uses, to proof of stake, which requires much less computing power and therefore does less damage to the environment. Briefly, you prove your work by doing those quintillions of calculations. You prove your stake by pledging cryptocoins that you own. As in a company’s shareholder vote, the people with the most coins have the biggest say.

The difference in energy consumed per transaction between the two systems is like the difference in height between the world’s tallest building and a single screw, according to one creative comparison. Once Ethereum makes the switch, Bitcoin will be the only one of the most highly valued cryptocurrencies using proof of work.

The European Parliament is moving toward insisting that all cryptocurrencies meet environmental sustainability standards, although in March a draft document stopped short of banning the proof-of-work system that Bitcoin uses. Also in March, Greenpeace USA, the Environmental Working Group, and other environmental advocacy groups began the Change the Code campaign, which involves advertising as well as putting pressure on cryptocurrency fanboys like Elon Musk of Tesla and Jack Dorsey of Block (formerly Square), as well as Abigail Johnson of Fidelity Investments, which manages mutual funds that invest in Bitcoin miners. The campaign got a $5 million boost from Chris Larsen, the executive chairman, a former chief executive and a co-founder of Ripple, a blockchain company for global enterprises.

There is no Bitcoin headquarters that you can call for an official response on this matter. Jameson Lopp, one of the currency’s defenders I spoke with, said, “There is no official anything when it comes to Bitcoin. There is no leader. There is only the protocol.”

Lopp, a co-founder and the chief technology officer of the Bitcoin storage company Casa, who describes himself as a professional cypherpunk, said it wasn’t up to people like him to defend Bitcoin. “I believe it defends itself. The game theory and the incentives are what keep this working. People can scream about environmental concerns all day long, but until you come up with a better system, it’s going to keep going.”

He and others also argue that Bitcoin isn’t as much of an energy hog as it first appears. Because Bitcoin miners can rapidly turn on or off, they are stabilizing the electrical grid in places such as Texas by throttling back when other demand is high and cranking up consumption when other demand is weak, advocates argue. Some of the electricity that Bitcoin uses is from energy resources that nobody else can easily access, such as overbuilt hydroelectric power plants, they say. (There’s some truth to this, but Bitcoin mining still contributes to global warming.)

Another Bitcoiner argument is that its proof of work method is more secure than proof of stake or other protocols. “The open question is not whether proof of stake is secure but whether it’s secure enough for a global form of digital gold. Bitcoin is,” said Ryan Selkis, a co-founder and the chief executive of Messari, which builds data and research tools for crypto. (Backers of proof-of-stake cryptos respond that their systems are just as secure as Bitcoin’s. “They’re literally being attacked by every hacker on earth, constantly. And they’re holding up,” said Larsen.)

There’s also some bad blood between the Bitcoin community and Larsen, whose company, Ripple, uses a security system that isn’t proof of work or proof of stake. In March, Selkis called Larsen a “Judas” on Twitter. The Securities and Exchange Commission sued Ripple, Larsen, and another Ripple executive in 2020, charging that its sale of $1.3 billion in crypto tokens constituted an “unregistered, ongoing digital asset securities offering.” In an interview, Larsen said he thinks the S.E.C. is wrong because Ripple is a virtual currency and is thus exempt from securities regulation.

Make of those arguments what you will; the important fact is that there’s no evidence that the key players in Bitcoin are interested in making the big switch to energy-saving proof of stake. It wouldn’t benefit the miners, who have invested heavily in specialized computing technology that would go to waste. And there’s no groundswell for it in the other key interest group, the operators of nodes — computers that keep up-to-date digital records of crypto transactions. The node operators collectively decide whether each new block of transactions should or should not be legitimized and appended to the blockchain. Some fear that moving to proof of stake would diminish Bitcoin’s decentralization, which they value.

It’s possible that some Bitcoiners will decide to switch to proof of stake. That would be what the community calls a hard fork, as in a fork in the road, where people have to choose which direction to go. But “even if there is a fork, that fork will eventually fail, and it will have zero or close to zero economic value,” said Daniel Frumkin, the director of research at Braiins, a Bitcoin-mining software company that operates a network of miners called Slush Pool.

For Bitcoin to change direction would require “almost like a constitutional convention of sorts,” said Selkis. “Inertia usually wins.”

OK, but what if the European Parliament does ban proof of work someday and the United States and other nations follow suit? That’s the nightmare scenario for the Bitcoin community, which has a strong libertarian streak. “Bitcoin would not be a trillion-dollar asset if the European Union and the United States were doing their jobs” of maintaining sound money, Selkis said. “That’s the real reason they don’t like it. It exposes their underperformance.”

“At least as of today, there is no one world, global government,” said Lopp. “There will always be somewhere that these miners will be able to go.” He laughed and added, “Worst-case scenario, they could all go to El Salvador, which loves Bitcoin.” (El Salvador adopted Bitcoin as an official currency in September, though the experiment has had some hiccups.)

I see lots of reasons for Bitcoin to stick with its current game plan. Quintillions of reasons, actually.