CANADA

Temperatures over 40 Celcius, longer heatwaves: report offers advice to adapt

Unless governments, communities, property managers, and individual Canadians act, a new report by researchers at the University of Waterloo suggests heat-related deaths in Canada will double by 2080.

That’s under its best-case scenario. Under its worst, it predicts those deaths will increase by 450 per cent over rates from the last half-century.

The report stresses governments need to recognize extreme heat events as natural disasters the same way it classifies flooding and wildfires. It says 17-million Canadians living in cities and towns are vulnerable, and Southwestern Ontario should anticipate some of the worst impacts.

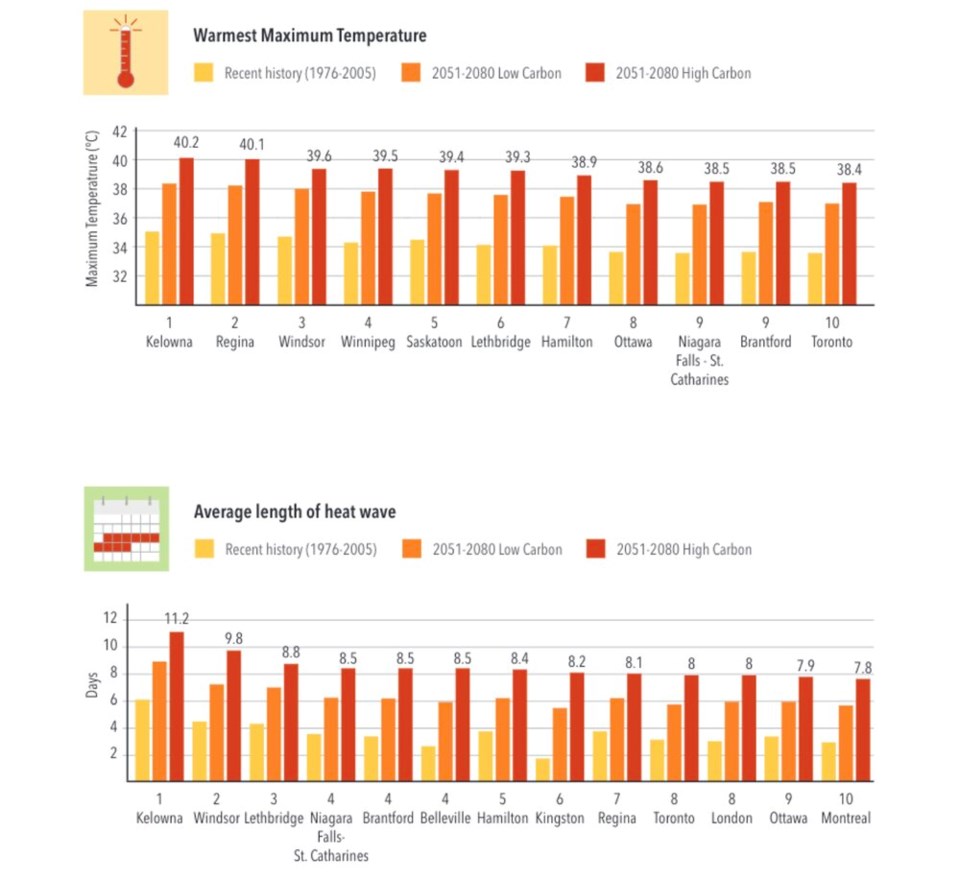

In Windsor, “Irreversible Extreme Heat: Protecting Canadians and Communities from a Lethal Future” suggests between 2051 and 2080, the number of extreme heat days, those with temperatures over 30 Celcius, could increase from the current 23 to 79 days a year under a high carbon model. Maximum temperatures will jump to 40 degrees, and the duration of heatwaves could be 9.8 days.

In comparison, between 1976 and 2005, Windsor’s maximum temperature was 35 Celcius on average, and heat waves typically lasted four days maximum.

London could anticipate 61 days a year with temperatures over 30 Celcius and heat waves that last eight days.

The report did not provide projections for Chatham-Kent, Sarnia, or Leamington but did say those communities are also at risk.

Pavement on Hwy 3 in Tecumseh buckles in heat on July 15, 2018. Photo courtesy Gary McNamara/Twitter.

Not only are lives and the healthcare system at stake, but infrastructure like roads, railways, and bridges could fail in extreme temperatures while failing crops threaten food security. It also suggested cities that suffer the worst heat could see more crime as mental health and the economy suffer.

While air conditioning has helped Canadians weather the worst impacts of heat so far, it may offer less benefit in the years to come because it requires electricity. As demand grows during hot days, greenhouse gas emissions rise, and power grids could fail.

However, the Intact Centre for Climate Adaptation also said Canadians are not helpless in the face of rising temperatures. It points out that heat-related deaths are preventable, and adaptation is possible.

There is no doubt the document offers some dire predictions for the next six decades. It also recommends actions individual Canadians, property owners, and communities can take. Some have already started to adapt.

Individual Canadians might consider using ceiling and portable fans more, improving home insulation, installing window coverings like shutters, and modifying living, working, and sleeping arrangements.

30 maple trees were planted as part of the Diamond Project in Durham. (Photo courtesy of the Diamond Project via Facebook)

Both individuals and communities can plant more trees, but cities and towns are encouraged to promote green roofs and building facades. Property managers can prompt apartment dwellers to create balcony gardens.

Municipalities can develop extreme heat emergency plans, extend opening hours at beaches, public pools, water parks, and cooling centres, and offer free public transportation to those locations that offer residents respite. Patrols could check on residents in disadvantaged neighbourhoods, and flexible hours might keep outside workers safe.

These B.C. cities will get hit hardest by future heat waves

Kelowna is projected to face the longest-lasting heat waves and the hottest maximum temperatures of any major Canadian city, a new report says.

The report, published Wednesday from the Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation, outlines several measures tenants, landlords and communities can take to prepare for the fallout from extreme heat.

Modelling heat waves between 2051 and 2080, the researchers found Kelowna will become among the top 10 “hottest” metropolitan areas in Canada.

Smaller Interior communities like Kamloops, Penticton, Creston and Vernon are also expected to reach similar temperatures.

In another metric, Windsor, Ont., is expected to have the most number of very hot days with an average of 78.8 days over 30 C under high-emission scenarios. In that field, Kelowna came in fourth after three other southern Ontario cities.

Over 17 million urban Canadians are expected to face extreme heat in the coming years. The report also warns of “red zones” in low-lying areas in B.C., southern Prairies, the St. Lawrence River valley in Quebec, and regions north of Lake Erie in Ontario.

Whereas flooding and wildfire — expected to increase in frequency and intensity this century — will cost Canada vast sums of money, heat waves will ramp up as a kind of silent killer.

“The impacts of heat are death,” said lead author Joanna Eyquem, managing director of Climate Resilient Infrastructure at the centre.

The parts of the country expected to be hit with the hottest heat for the longest aren’t always the most vulnerable. Heat waves that occur outside of the summer or in communities unaccustomed to extreme heat can face massive human casualties, as was seen in Metro Vancouver last summer when nearly hundreds died alone in hot, poorly ventilated rooms.

Eyquem called on all levels of government to start taking extreme heat more seriously.

After last year’s heat wave in B.C., Eyquem said she expected to see a growing recognition of heat’s deadly potential. But when she looked at Canada’s federal disaster database, it still failed to mention the disaster.

On a Health Canada webpage outlining its role in a disaster, Eyquem said the agency did not include extreme heat among other risks like earthquakes, floods and outbreaks of disease.

“It’s not seen as an emergency,” she said.

To date, local governments have largely been left on their own to deal with extreme heat — whether creating cooling centres or deploying misting fountains. But as the COVID-19 pandemic has shown, provincial and federal governments play key roles providing funding, coordinating action plans and delivering messages.

In the interim, an individual who chooses to adapt their home to extreme heat also makes life more comfortable and affordable at the same time.

And while the report doesn’t specifically target Indigenous communities or the acute challenges of Canada’s North, Eyquem says it offers a baseline for action at the local level.

“There are simple things, even just sticking up some window films to kind of cut the sun coming through your windows,” she said.

“That's very affordable. So I don't know why we're not doing that.”

This ‘silent killer’ of climate change may hit 17 million Canadians the hardest. Here’s what a new report suggests as protection

APRIL 20, 2022

It’s floods that lead to repairs costing billions of dollars. It’s fires that burn images of charred buildings and communities into our minds.

But of all the extreme weather events made more likely by climate change, it’s another — extreme heat — that is the deadliest. And a new report by Canadian experts on climate adaptation says there are clear ways to make sure fewer Canadians die of extreme heat in the future.

Without action, the picture painted by a report on irreversible extreme heat from the Intact Center on Climate Adaptation — a University of Waterloo climate adaptation research center — is dire. The documentwhich is meant to instruct individuals, communities and higher levels of government in Canada to prepare for and avoid the worst effects of extreme heat, concluded that 17 million Canadians — including the population of Toronto — live in metropolitan areas that the report’s authors regard as at highest risk for extreme heat events.

In the best case scenario, with lower carbon emissions and stable population, the frequency and severity of extreme heat events until 2080 will mean 50 per cent more people are expected to die compared to the past 50 years for heat-related reasons.

In the worst case scenario — high carbon emissions and large population growth — the rate of excess deaths could be 450 per cent greater than in the last 50 years.

Joanna Eyquem, managing director of climate-resilient infrastructure at the Intact Center and the lead author of the report, said the high death toll from extreme heat — most recently highlighted by the heat dome in British Columbia that claimed 526 lives in eight days last year — make it apparent why adaptations to extreme heat events are urgently needed. Extreme heat, the report states, is the “silent killer” of climate change — and is avoidable.

“Heat-related deaths are avoidable, with the right action, information and adaptation,” Eyquem told the Star. “That’s something we can avoid.”

It’s not that Canadians have not been exposed to extreme heat before, and suddenly will be. Item explains that instances of extreme heat, usually defined as temperatures above 30 Care already more common as a result of climate change, and are likely only to become more common.

That has direct effects on our health, such as by causing heat stroke in people who can’t avoid the heat, and indirect effects, such as by exacerbating mental-health issues and keeping people indoors and alone.

And heat does not strike equally everywhere. The effects of extreme heat are much worse in urban environments, where concrete absorbs heat and fewer trees and plants are present to cast shade and retain cooling water.

“Not only are (artificial city) surfaces hotter during the day because they absorb all that solar heat, they give it out at night so we don’t get this cooling effect overnight,” she said. “That’s what we call this heat-island effect in cities.”

According to the report, urban environments can be 10 to 15 degrees hotter than rural areas on the same day for these reasons.

Older people, people with chronic conditions and people who live far away from green spaces are the most likely to be affected.

Fifteen metropolitan areas were identified as most at-risk for extreme heat in the future: Kelowna, Lethbridge, Regina, Saskatoon, Winnipeg, Windsor, Hamilton, Niagara Falls/St. Catharines, Brantford, London, Ottawa, Toronto, Belleville, Kingston and Montreal. A total of 17 million Canadians lived in these communities, per 2020 Statistics Canada estimates./https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/news/canada/2022/04/19/this-silent-killer-of-climate-change-may-hit-17-million-canadians-the-hardest-heres-what-a-new-report-suggests-as-protection/creek.jpg)

The Intact Centre, which consulted 60 experts for its guidance report, came up with 35 recommendations for tackling effects and deaths from extreme heat. It said that even with extreme heat events becoming much more common, deaths may not rise as much if these adaptations take place.

For individuals, the central recommendation is to make a plan for extreme heat in the way they might already have a fire or an earthquake plan. The plan would include noting any vulnerable family members you should check on in person during extreme heat, and identifying a cooling place you can go if your home is not adequately cool.

The report also recommends coming up with ways to passively cool your home if possible, such as with reflective window coverings or increasing plant areas.

The recommendations for property owners and managers also include coming up with an extreme heat plan, as well as playing a more active role in increasing green infrastructure such as trees on their properties, and maintaining designated air-conditioned cool rooms.

Communities are also encouraged to increase tree cover and vegetated areas, as well as to map which areas in the community are most vulnerable to extreme heat, prepare for extreme heat warnings, and provide incentives for owners and tenants to implement shaded areas.

Eyquem said it may not be intuitive for all Canadians to think about extreme heat, especially before the summer has started. But that’s exactly what she thinks we should do: Start thinking of heat as a climate disaster to prepare for in advance.

“I think in Canada we still have a cold climate mentality, we’re more worried about heating than cooling,” she said. “But that’s going to shift in the future. We’re warming twice as fast as the rest of the world.”

And, she said, heat is a good example of how climate change is not only an issue with carbon emissions and preventing environmental disaster.

“It’s framed as an environment issue,” she said. “But really it’s a health issue. There’s a lack of awareness that this is going to be important going forward for our health.”

Alex McKeen is a Vancouver-based reporter for the Star. Follow her on Twitter: @alex_mckeen

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/news/gta/2022/04/16/torontos-new-wealth-gap-is-driven-by-real-estate-not-income-where-those-who-got-in-early-can-live-a-very-different-life/B881669971Z.1_20220414173350_000+GR01GFPGO.4-0.jpg)