INDIA

Suicidal Tendencies Among Death Row Prisoners Raise Serious Questions About the State’s Responsibility, Says the Team From NLU-D’s Project 39A

The mental health condition of death row prisoners who have been languishing in prisons due to delay in processing of their mercy petitions, and other legal remedies in the appellate courts, has been a mystery. In this interview, the team from NLU-D’s Project 39A.

Gursimran Kaur Bakshi

13 May 2022

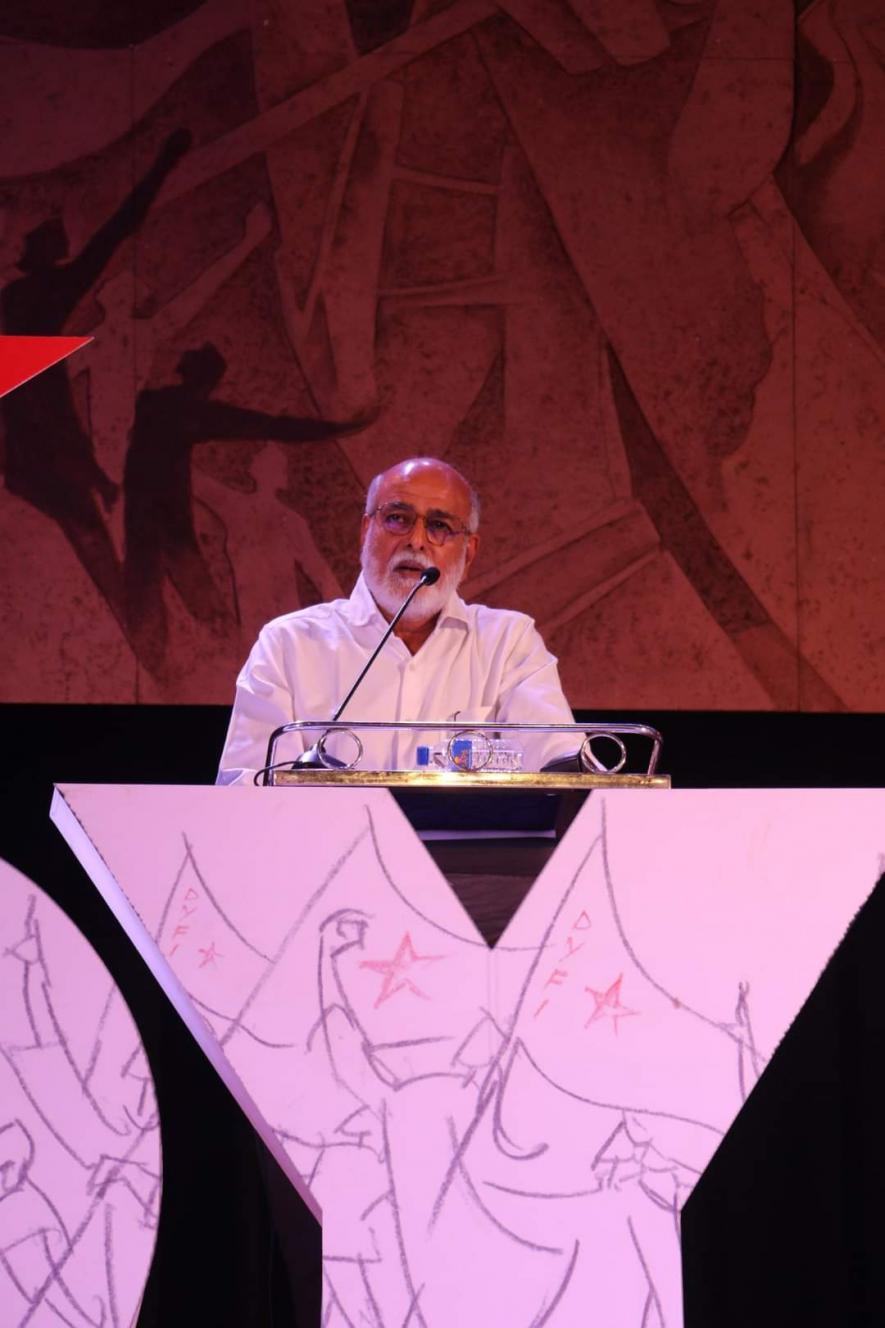

Courtesy: NLU-D’s Project 39A

The mental health condition of death row prisoners who have been languishing in prisons due to delay in processing of their mercy petitions, and other legal remedies in the appellate courts, has been a mystery. In this interview, the team from NLU-D’s Project 39A – which has collected the requisite data – sheds some light to unravel it.

—–

In December 2021, the Supreme Court bench comprising Justices L. Nageswara Rao, B.V Nagarathna and B.R Gavai acquitted three death row convicts (Momin, Jaikam and Sajid) in Jaikam Khan versus The State of Uttar Pradesh, after they had already spent eight years in prison. The bench remarked that their conviction and death sentence imposed is totally unsustainable in law.

As per the empirical report ‘Deathworthy’ published by the National Law University, Delhi’s [NLU-D] Project 39A, it has been found that more than 60% of prisoners on death row suffer from some kind of mental illness.

As we commemorate Mental Health Awareness Month, it has been realised that the present laws namely, Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 [MHCA], Prisons Act, 1894 and the Model Prison Manual, 2016 do not substantively address the mental health rights of prisoners.

The 1894 Act only gives a definition of a sick prisoner as someone who ‘appears out of health in mind or body’. Whereas, the MHCA does not have provisions to address the mental well-being of prisoners. It does have provisions, such as Section 113, that provide for a prisoner with mental illness to be shifted to the psychiatric ward of the medical wing of the prison. According to the Model Prison Manual, there is ‘one’ Psychologist/counsellor for every ‘500 prisoners’.

To get a closer understanding of the mental health conditions of prisoners, The Leaflet asked a few questions from the team of Project 39A based at the NLU-D. These questions have been answered by Dr. Anup Surendranath, Executive Director of Project 39A and an Assistant Professor of Law at the NLU-D; CP Shruthi, Mitigation Associate; and Medha Deo, Programme Director for Fair Trial Fellowship.

Project 39A aims to trigger new conversations on legal aid, torture, forensics, mental health in prisons, and the death penalty by using empirical research to re-examine practices and policies in the criminal justice system.

Excerpts from the interview:

Q: Project 39A published various empirical studies on the mental health of prisoners on death row. Please tell us about the findings of those reports. Also, what all categories of prisoners require mental healthcare facilities?

A: ‘Deathworthy’ is a first of its kind empirical and descriptive study to take a psychosocial approach to understanding the mental health of death row prisoners in India. It presents empirical data on mental illness and intellectual disability among death row prisoners in India and the psychological consequences of living on death row.

Also read: 62.2% death row prisoners diagnosed with at least one mental illness: Study

As a part of this study, we interviewed 88 death row prisoners and their families across five states (Chhattisgarh, Delhi, Karnataka, Kerala and Madhya Pradesh).

We also found that an overwhelming majority of death row prisoners interviewed (62.2%) had a mental illness and 11% had an intellectual disability.

The report essentially charts out the life of these prisoners, the implication of poverty and other vulnerabilities that they are exposed to and what happens to them when they come to prison. We found that there were high instances of certain kinds of mental illnesses, what we also call the pains of death row.

We also found that an overwhelming majority of death row prisoners interviewed (62.2%) had a mental illness and 11% had an intellectual disability.

The proportion of persons with mental illness and intellectual disability on death row is overwhelmingly higher than the proportion in the community population.

I think all categories of prisoners require access to mental healthcare facilities. The prolonged period of incarceration and harsh conditions may exacerbate several other vulnerabilities, such as substance misuse problems, poor physical and mental health outcomes, learning difficulties, histories of trauma etc., among the prisoners. So the quality of care should encompass not only treatment but also therapy and care so as to minimize the chances of re-traumatizing individuals with a history of trauma.

Q: It’s said that people with mental illness are more likely to be victims of crime than perpetrators of crime. There are two concepts here-the mental illness and the legal capacity (defence of insanity) to commit the crime.

Can you explain to us the difference between the two in terms of being a mitigating factor in the commutation of sentencing?

A: The defence of insanity is what Section 84 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 [IPC] deals with. It is the “act of a person of unsound mind.”

This is a purely legal concept that deals with the ‘mental state’ of the person at the time of the commission of the act and exempts the individual of any criminal responsibility for the act as there is a loss of reasoning power with reference to the offence in question.

The threshold for claiming the insanity defence is so high that one needs to show that the individual was unable to appreciate the nature of the act or wrongdoing or that it was contrary to the law as it completely exempts them from any criminal responsibility.

While abnormality of mind or partial delusion, irresistible impulse or compulsive behaviour of a psychopath are recognised as psychiatric conditions, it affords no protection under Section 84 IPC.

On the other hand, when a mental health concern is presented as a mitigating factor, it is not a justification or an excuse for the crime but it is a fact or circumstance that in fairness or mercy, may be considered for reducing the degree of the defendant’s culpability for a death sentence. So, it looks at a much broader spectrum of mental health issues and concerns and not just psychiatric illness.

It involves taking a psycho-social approach to understanding the multitude of factors like adverse childhood experiences that an individual may have been exposed to, traumatic events that they have witnessed, previous history of physical and mental health issues, and any mental illness developed during the period of incarceration(post-conviction) and other vulnerabilities.

Q: I want to draw your attention to two specific cases- first, the acquittal of Momin, Jaikam and Sajid who spent eight years in prison including six years on death row. Project 39A has also covered this case. Second, recently the Supreme Court set an accused free by accepting his claim of juvenility after he had spent 17 years in prison. These are just two horrendous cases out of the many where the criminal justice system has failed its people.

We often say that the aim of the criminal justice system should be rehabilitation but is that really possible? Is there any post acquittal mental healthcare facility given to such types of persons who have been a victim of the unfairness of the Indian criminal justice system?

A: Project 39A was involved in the preparation and arguments of Momin, Jaikam and Sajid’s appeal at the Supreme Court. The last eight years have not been easy for these three men and their families. While they were pushed to the margins from multiple sites and it has had an impact on their financial, emotional, and mental well being, there is no specific institutional support that caters specifically to those wrongfully convicted or imprisoned.

The Model Prison Manual 2016 provides for steps to be taken to ensure the continuation of psychiatric treatment after release and provisions of social psychiatric after-care but it does not seem adequate to address issues such as re-adjustment and rehabilitation into the society after a long period of incarceration.

Providing mental healthcare for such prisoners would need a more holistic and trauma-informed approach that focuses not only on clinical recovery but social re-integration.

The threshold for claiming the insanity defence is so high that one needs to show that the individual was unable to appreciate the nature of the act or wrongdoing or that it was contrary to the law as it completely exempts them from any criminal responsibility.

Q: The suicide rate of prisoners is constantly rising. Many prisoners commit suicide because of the custodial settings we have. I want to refer to one of the convicts in the Nirbhaya gang-rape case who committed suicide before he was to be given the death penalty. How do you think the type of imprisonment impacts mental health, especially for those who are on death row or have suffered solitary confinement?

A: The death row population is precariously vulnerable to mental illness and to severe psychological harm in state custody. The long and harsh conditions of solitary confinement and lack of medical care further complicate their mental health condition. The findings of our report Deathworthy indicate that among the 88 prisoners interviewed during the course of the fieldwork, the main psychiatric illnesses found were Major Depressive Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Substance Use Disorder.

Also read: Mental Healthcare Act: issues of intersectionality and stigma need to be addressed

Prisoners also reported having psychotic episodes in prison – one of whom had a psychotic episode while in solitary confinement. Close to 50% of prisoners had thoughts of dying by suicide and eight attempted to die by suicide. This raises serious concerns about the responsibility of the State to provide for quality mental health care facilities to prevent and address the mental health crisis among the death row population.

Q: Lastly, I want you to address the current mental healthcare facilities provided to prison inmates as per the Model Prison Manual. Also, please tell us about the Supreme Court’s guidelines on the detention of mentally ill undertrial prisoners and how far those guidelines have been successful.

A: Prisoners with mental illness are kept in a separate ward according to the Model Prison Manual and there are psychiatrists checking up on them regularly but they are mostly prescribed general medicines which keep them feeling drowsy throughout the day so as to keep them from causing trouble.

Recent Supreme Court judgments have pushed for psychological evaluation of a prisoner but in the lower courts, there is still a substantial delay in getting that done despite the under trial prisoner showing overt symptoms of mental illness. In one case, the prisoner was diagnosed having schizophrenia and shifted to the regional mental hospital for some time but then brought back and declared fit for trial even when his mental health had not improved.

Gursimran Kaur Bakshi is a staff writer at The Leaflet

Courtesy: The leaflet

The mental health condition of death row prisoners who have been languishing in prisons due to delay in processing of their mercy petitions, and other legal remedies in the appellate courts, has been a mystery. In this interview, the team from NLU-D’s Project 39A.

Gursimran Kaur Bakshi

13 May 2022

Courtesy: NLU-D’s Project 39A

The mental health condition of death row prisoners who have been languishing in prisons due to delay in processing of their mercy petitions, and other legal remedies in the appellate courts, has been a mystery. In this interview, the team from NLU-D’s Project 39A – which has collected the requisite data – sheds some light to unravel it.

—–

In December 2021, the Supreme Court bench comprising Justices L. Nageswara Rao, B.V Nagarathna and B.R Gavai acquitted three death row convicts (Momin, Jaikam and Sajid) in Jaikam Khan versus The State of Uttar Pradesh, after they had already spent eight years in prison. The bench remarked that their conviction and death sentence imposed is totally unsustainable in law.

As per the empirical report ‘Deathworthy’ published by the National Law University, Delhi’s [NLU-D] Project 39A, it has been found that more than 60% of prisoners on death row suffer from some kind of mental illness.

As we commemorate Mental Health Awareness Month, it has been realised that the present laws namely, Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 [MHCA], Prisons Act, 1894 and the Model Prison Manual, 2016 do not substantively address the mental health rights of prisoners.

The 1894 Act only gives a definition of a sick prisoner as someone who ‘appears out of health in mind or body’. Whereas, the MHCA does not have provisions to address the mental well-being of prisoners. It does have provisions, such as Section 113, that provide for a prisoner with mental illness to be shifted to the psychiatric ward of the medical wing of the prison. According to the Model Prison Manual, there is ‘one’ Psychologist/counsellor for every ‘500 prisoners’.

To get a closer understanding of the mental health conditions of prisoners, The Leaflet asked a few questions from the team of Project 39A based at the NLU-D. These questions have been answered by Dr. Anup Surendranath, Executive Director of Project 39A and an Assistant Professor of Law at the NLU-D; CP Shruthi, Mitigation Associate; and Medha Deo, Programme Director for Fair Trial Fellowship.

Project 39A aims to trigger new conversations on legal aid, torture, forensics, mental health in prisons, and the death penalty by using empirical research to re-examine practices and policies in the criminal justice system.

Excerpts from the interview:

Q: Project 39A published various empirical studies on the mental health of prisoners on death row. Please tell us about the findings of those reports. Also, what all categories of prisoners require mental healthcare facilities?

A: ‘Deathworthy’ is a first of its kind empirical and descriptive study to take a psychosocial approach to understanding the mental health of death row prisoners in India. It presents empirical data on mental illness and intellectual disability among death row prisoners in India and the psychological consequences of living on death row.

Also read: 62.2% death row prisoners diagnosed with at least one mental illness: Study

As a part of this study, we interviewed 88 death row prisoners and their families across five states (Chhattisgarh, Delhi, Karnataka, Kerala and Madhya Pradesh).

We also found that an overwhelming majority of death row prisoners interviewed (62.2%) had a mental illness and 11% had an intellectual disability.

The report essentially charts out the life of these prisoners, the implication of poverty and other vulnerabilities that they are exposed to and what happens to them when they come to prison. We found that there were high instances of certain kinds of mental illnesses, what we also call the pains of death row.

We also found that an overwhelming majority of death row prisoners interviewed (62.2%) had a mental illness and 11% had an intellectual disability.

The proportion of persons with mental illness and intellectual disability on death row is overwhelmingly higher than the proportion in the community population.

I think all categories of prisoners require access to mental healthcare facilities. The prolonged period of incarceration and harsh conditions may exacerbate several other vulnerabilities, such as substance misuse problems, poor physical and mental health outcomes, learning difficulties, histories of trauma etc., among the prisoners. So the quality of care should encompass not only treatment but also therapy and care so as to minimize the chances of re-traumatizing individuals with a history of trauma.

Q: It’s said that people with mental illness are more likely to be victims of crime than perpetrators of crime. There are two concepts here-the mental illness and the legal capacity (defence of insanity) to commit the crime.

Can you explain to us the difference between the two in terms of being a mitigating factor in the commutation of sentencing?

A: The defence of insanity is what Section 84 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 [IPC] deals with. It is the “act of a person of unsound mind.”

This is a purely legal concept that deals with the ‘mental state’ of the person at the time of the commission of the act and exempts the individual of any criminal responsibility for the act as there is a loss of reasoning power with reference to the offence in question.

The threshold for claiming the insanity defence is so high that one needs to show that the individual was unable to appreciate the nature of the act or wrongdoing or that it was contrary to the law as it completely exempts them from any criminal responsibility.

While abnormality of mind or partial delusion, irresistible impulse or compulsive behaviour of a psychopath are recognised as psychiatric conditions, it affords no protection under Section 84 IPC.

On the other hand, when a mental health concern is presented as a mitigating factor, it is not a justification or an excuse for the crime but it is a fact or circumstance that in fairness or mercy, may be considered for reducing the degree of the defendant’s culpability for a death sentence. So, it looks at a much broader spectrum of mental health issues and concerns and not just psychiatric illness.

It involves taking a psycho-social approach to understanding the multitude of factors like adverse childhood experiences that an individual may have been exposed to, traumatic events that they have witnessed, previous history of physical and mental health issues, and any mental illness developed during the period of incarceration(post-conviction) and other vulnerabilities.

Q: I want to draw your attention to two specific cases- first, the acquittal of Momin, Jaikam and Sajid who spent eight years in prison including six years on death row. Project 39A has also covered this case. Second, recently the Supreme Court set an accused free by accepting his claim of juvenility after he had spent 17 years in prison. These are just two horrendous cases out of the many where the criminal justice system has failed its people.

We often say that the aim of the criminal justice system should be rehabilitation but is that really possible? Is there any post acquittal mental healthcare facility given to such types of persons who have been a victim of the unfairness of the Indian criminal justice system?

A: Project 39A was involved in the preparation and arguments of Momin, Jaikam and Sajid’s appeal at the Supreme Court. The last eight years have not been easy for these three men and their families. While they were pushed to the margins from multiple sites and it has had an impact on their financial, emotional, and mental well being, there is no specific institutional support that caters specifically to those wrongfully convicted or imprisoned.

The Model Prison Manual 2016 provides for steps to be taken to ensure the continuation of psychiatric treatment after release and provisions of social psychiatric after-care but it does not seem adequate to address issues such as re-adjustment and rehabilitation into the society after a long period of incarceration.

Providing mental healthcare for such prisoners would need a more holistic and trauma-informed approach that focuses not only on clinical recovery but social re-integration.

The threshold for claiming the insanity defence is so high that one needs to show that the individual was unable to appreciate the nature of the act or wrongdoing or that it was contrary to the law as it completely exempts them from any criminal responsibility.

Q: The suicide rate of prisoners is constantly rising. Many prisoners commit suicide because of the custodial settings we have. I want to refer to one of the convicts in the Nirbhaya gang-rape case who committed suicide before he was to be given the death penalty. How do you think the type of imprisonment impacts mental health, especially for those who are on death row or have suffered solitary confinement?

A: The death row population is precariously vulnerable to mental illness and to severe psychological harm in state custody. The long and harsh conditions of solitary confinement and lack of medical care further complicate their mental health condition. The findings of our report Deathworthy indicate that among the 88 prisoners interviewed during the course of the fieldwork, the main psychiatric illnesses found were Major Depressive Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Substance Use Disorder.

Also read: Mental Healthcare Act: issues of intersectionality and stigma need to be addressed

Prisoners also reported having psychotic episodes in prison – one of whom had a psychotic episode while in solitary confinement. Close to 50% of prisoners had thoughts of dying by suicide and eight attempted to die by suicide. This raises serious concerns about the responsibility of the State to provide for quality mental health care facilities to prevent and address the mental health crisis among the death row population.

Q: Lastly, I want you to address the current mental healthcare facilities provided to prison inmates as per the Model Prison Manual. Also, please tell us about the Supreme Court’s guidelines on the detention of mentally ill undertrial prisoners and how far those guidelines have been successful.

A: Prisoners with mental illness are kept in a separate ward according to the Model Prison Manual and there are psychiatrists checking up on them regularly but they are mostly prescribed general medicines which keep them feeling drowsy throughout the day so as to keep them from causing trouble.

Recent Supreme Court judgments have pushed for psychological evaluation of a prisoner but in the lower courts, there is still a substantial delay in getting that done despite the under trial prisoner showing overt symptoms of mental illness. In one case, the prisoner was diagnosed having schizophrenia and shifted to the regional mental hospital for some time but then brought back and declared fit for trial even when his mental health had not improved.

Gursimran Kaur Bakshi is a staff writer at The Leaflet

Courtesy: The leaflet