National Geographic

Rachel Fobar -

© Photograph by PETA

More than 5,000 dogs were crowded in small, barren cages lined with feces and mold. A three-week-old puppy was stuck in a waste pan under his cage, dried feces matting his fur. Fights between kennel mates had left some dogs dead, including one by “evisceration.”

These violations and dozens more were documented in recent United States Department of Agriculture public inspection reports. Yet for months, the USDA, which is responsible for enforcing the Animal Welfare Act, neither confiscated any dogs nor suspended or revoked the license of the animal-breeding facility in Cumberland, Virginia. The facility is owned by Envigo, a privately held company with 20 locations across North America and Europe that provides animals for pharmaceutical and biomedical research.

© Photograph by PETA

In early May, National Geographic approached the USDA for comment about the facility’s history of violations and ongoing welfare problems. On May 18, authorities from the USDA and the Department of Justice confiscated 145 dogs in need of immediate medical care from Envigo’s facility in Cumberland, Virginia, according to a complaint filed the next day by the DOJ in federal court against Envigo. The Humane Society of the United States assisted in the seizures.

© Photograph by Humane Society

“Envigo’s disregard for the law and the welfare of the beagles in its care has resulted in the animals’ needless suffering and, in some cases, death,” according to the DOJ complaint.

The USDA and the DOJ declined to comment.

The lack of punitive action before May 18, given the gravity and number of the violations, has shocked and mystified animal welfare advocates.

“It is baffling” that the USDA repeatedly cited Envigo without rendering “immediate aid to those animals,” said Daphna Nachminovitch, senior vice president of cruelty investigations for People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, which carried out a separate undercover investigation at Envigo last year.

© Photograph by Humane Society

It isn’t just animal welfare activists who raised the alarm; outrage over the violations have become a bipartisan rallying point. In early April, Virginia’s Republican governor, Glenn Youngkin, signed five “beagle bills” to protect research animals and block dealers from doing business after severe welfare violations.

U.S. Senators Mark Warner and Tim Kaine, both Democrats, wrote to the USDA urging it to “pursue aggressive enforcement actions” against Envigo. “In light of persistent and egregious violations” of the Animal Welfare Act, the senators urged the department to “immediately suspend the license of the Envigo breeding facility in Cumberland and initiate formal administrative proceedings.”

Envigo breeds beagles as well as primates, rabbits, and rodents for use in toxicology research and other medical experiments. The Virginia facility is a member of the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International, or AAALAC, an accrediting body that conducts site visits every three years.

Businesses that profit from certain species of animals must be licensed under the Animal Welfare Act, which requires them to be inspected regularly by the USDA to ensure compliance. In four visits to the Cumberland operation since July 2021—most recently in March 2022—USDA inspectors documented more than 70 welfare violations. They found that 13 beagle mothers who were nursing litters of six-week-old puppies, 78 in all, had gone without food for 42 hours. According to the inspectors’ report, Envigo deprived the mothers to reduce their milk production as part of its “weaning of puppies” procedure.

To have so many violations is “unheard of,” Nachminovitch says. And considering their severity, “it’s chilling.”

The confiscated beagles will be placed “with rescue and shelter partners for adoption after their immediate needs are tended to,” according to the Humane Society.

In a statement given to National Geographic prior to the seizure of dogs, Envigo spokesperson Mark Hubbard said the facility has made improvements in recent months, including reducing the number of dogs on-site, hiring a second veterinarian, performing more than 2,700 physical examinations, and increasing staff salaries. “We are aware the USDA has issued another inspection report that essentially repeats earlier findings, all of which are being addressed through a comprehensive remediation plan that has been in progress,” he wrote.

Hubbard also said that the USDA recognizes improvements Envigo has made and that AAALAC has indicated that the facility should continue to receive accreditation. Hubbard couldn’t immediately be reached for comment about the seizures.

Yet the pattern of welfare violations at what is now Envigo dates back decades. USDA records also show that Huntingdon Life Sciences, which later merged with Harlan Labs to form Envigo, has had violations going back to the late 1990s. Citations from a 1997 report on Huntingdon showed “severe” suffering at a New Jersey facility—including a dog with an untreated broken leg, a drugged dog that was recommended for euthanasia but was not put down, and primates crying out and vomiting, unattended by a veterinarian.

Envigo’s record is an “unmitigated, unprecedented disaster,” says Eric Kleiman, a researcher at the Animal Welfare Institute, a nonprofit organization based in Washington, D.C.

USDA’s spotty enforcement record

National Geographic has documented a pattern of USDA failure to take action over animal welfare violations during the past several years, marked by a 90 percent drop in enforcement actions against licensed animal facilities between 2015 and 2020. There were two high-profile license revocations late last year.

In October 2021, the department revoked the license of Moulton Chinchilla Ranch in Minnesota after citing it for more than a hundred violations dating back to 2013; inspectors had found filthy cages, decomposing carcasses, and accumulated feces. Less than a month later, the USDA revoked the license of Iowa dog breeder Daniel Gingerich after multiple inspections over six months. Dogs had heavily matted coats and skin conditions, and many were seen panting in the summer heat, their water bowls empty. At least three dogs were found dead.

In comparison, more than 300 puppies died at Envigo’s Cumberland branch between January 1 and July 20, 2021, and “the facility has not taken additional steps to determine the causes of death,” according to the USDA report. Yet for months, the department failed to take any action.

One veterinarian for 5,000 dogs

Not attempting to establish why the dogs died violates the Animal Welfare Act. At the time of the USDA’s July and October 2021 inspections, Envigo had only one staff veterinarian to attend to 5,000 dogs. The USDA’s numerous veterinary care citations are “evidence that [one veterinarian] is an insufficient number,” Kleiman says.

The USDA’s inspection policy requires a follow-up visit within 14 days of a “direct” citation, a violation that has a “serious or adverse effect on the health and well-being of the animal.” In the July 20 report, inspectors noted seven direct non-compliances, including food deprivation, cramped living spaces, and inadequate veterinary care for ear infections and oozing wounds. Yet inspectors didn’t return as required to Cumberland for three months. In November 2021 and March 2022, inspectors documented more direct citations, but again failed to re-inspect within 14 days.

The Animal Welfare Act also requires that whenever the USDA believes a business is “placing the health of any animal in serious danger,” the department must notify the U.S. Attorney General, who has the discretion to prosecute the case in federal court.

‘Prolonged, unalleviated pain’

A recent investigation of another facility accredited by AAALAC indicates that Envigo’s welfare problems are not isolated.

Inotiv—a rapidly expanding multinational pharmaceutical development company that breeds, sells, and conducts toxicology and other experiments on animals—reported $89.6 million in revenue last year, when it acquired Envigo. Inotiv owns about 62,000 animals, including monkeys, rabbits, and cats, as well as the thousands of beagles.

In a seven-month undercover investigation of an Inotiv laboratory in Mount Vernon, Indiana, released on April 21, the Humane Society of the United States found that dogs, primates, pigs, mice, and rats faced “prolonged, unalleviated pain” during toxicology tests before they died.

Toxicology tests assess an animal’s tolerance to drugs. Doses administered by injection or feeding tube are increased until the animal experiences adverse effects.

In a statement, Inotiv spokesperson Kate Snedeker said the company is “governed by applicable federal, state, and local regulations,” as well as its internal animal care guidelines and oversight by the USDA and AAALAC.

“The research we conduct is required by global governmental regulatory agencies before new life-saving drugs can be brought to the market,” she wrote. “For more than 20 years, Inotiv has participated, directly and indirectly, in studying and developing alternative methods to conduct biomedical research.” Snedeker could not be immediately reached for comment about the seizures at Envigo’s Cumberland facility.

The Food and Drug Administration, which approves drugs for human use, says drug companies do animal tests “to discover how the drug works and whether it’s likely to be safe and work well in humans.” But the agency doesn’t mandate animal trials.

Yet drug companies routinely conduct tests on animals because it’s “the status quo,” says Kitty Block, the Humane Society’s president. “There’s big money in breeding these animals and then using them.” She considers the reliance on animal testing “lazy,” and says the FDA should promote innovative, humane drug-testing methods such as organ-on-a-chip technologies, 3D printing of human tissues, and computer modeling instead.

FDA press officer Veronika Pfaeffle said her agency aims to “reduce the reliance on animal-based studies” and has taken significant steps in “replacing, reducing, and/or refining” them, including forming working groups to advance new technologies. But “there are still many areas where animal research is scientifically necessary,” she said.

For example, alternative approaches “cannot always predict side effects” that might occur in the human body, she said, adding that animal research has been instrumental in advancing drugs to prevent polio, eradicate smallpox, and vaccinate against and treat COVID-19.

When necessary for research, the animals involved “should be cared for under strict, humane guidelines,” Pfaeffle said.

‘This is a nasty business’

But the FDA isn’t responsible for ensuring humane treatment of animals; that falls to the USDA and AAALAC. If, for example, an animal is in extreme distress, the USDA requires facilities to “ensure that animal pain and distress are minimized” and to have a protocol for euthanizing animals.

Yet at Inotiv’s Indiana facility, the Humane Society’s investigator saw researchers continuing to administer doses of drugs to animals that were shaking, vomiting, and had labored breathing. According to the report, an Inotiv technician, under orders from the veterinarian, continued to dose a primate in obvious distress, while saying, “I’m so sorry, lady—maybe this will be your last dose. I kind of hope it is because it’s torture at this point.”

Inotiv’s Indiana lab, with more than 1,300 animals, had only one full-time veterinarian between August 2021 and March 2022, according to the Humane Society’s investigation. Fewer than 50 staff were spread so thinly that basic care, such as trimming dogs’ toenails, was neglected, according to the Humane Society. Primates were left unattended in restraint chairs, and two accidentally hanged themselves, the investigator reported.

Animal welfare experts are critical not just of the USDA’s reluctance to take action over infractions, but also of what they consider to be AAALAC’s weak oversight. The industry’s accreditation agency schedules site visits only once every three years and, according to the Animal Welfare Institute, has a history of dismissing welfare problems that violate the USDA’s guidelines. AAALAC’s reports are not made public.

The organization’s accreditation isn’t “even close to being sufficient” to ensure animal welfare, Block says. It’s “the proverbial fox guarding the hen house.”

Kathryn Bayne, the global director of AAALAC, defended her organization, writing in an email that “AAALAC International takes very seriously information received regarding compromised research animal welfare at an institution participating in the accreditation program. Investigations are ongoing.”

The USDA’s most recent inspection of Inotiv’s lab, in August 2021, cited no infractions, despite multiple violations documented by the Humane Society investigation at the same time. The multiple severe violations documented at Envigo’s facility and the alleged failure to follow euthanasia procedures at Inotiv’s should be a wakeup call for the USDA to ramp up its oversight and enforcement of animal breeding and research companies, Kleiman says. “Research won’t police itself.”

Kleiman says the USDA should send an unequivocal message that “no matter how large, how powerful, how wealthy” these companies are, animal suffering won’t be tolerated.

“This is a nasty business," Block says. “There’s cruelty everywhere, from the beginning of it to the end.”

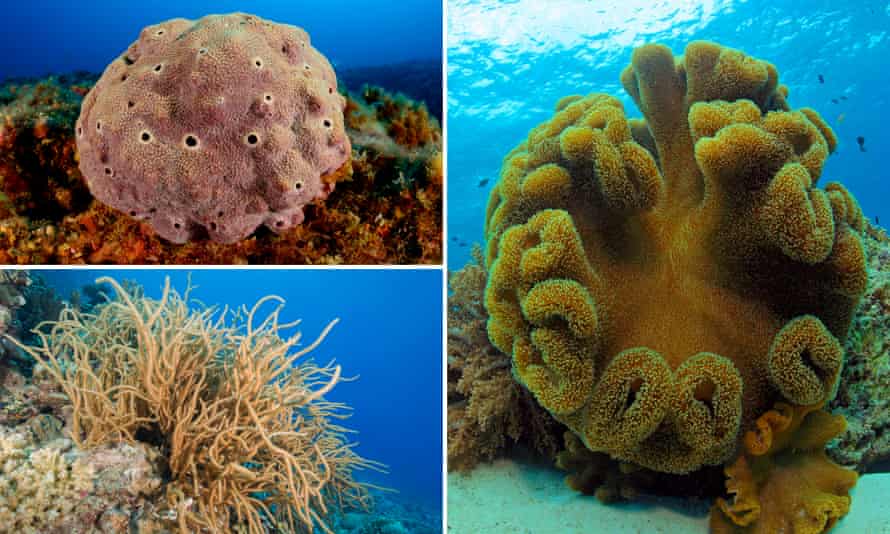

Manufacturers are either intentionally or unintentionally adding chemicals to packaging, said a report co-author. Either way, many of those chemicals are ending up in the human body, he said. Photograph: Sergio Azenha/Alamy

Manufacturers are either intentionally or unintentionally adding chemicals to packaging, said a report co-author. Either way, many of those chemicals are ending up in the human body, he said. Photograph: Sergio Azenha/Alamy