New measurements from Northern Sweden show less methane emissions than feared

GREENHOUSE GASES

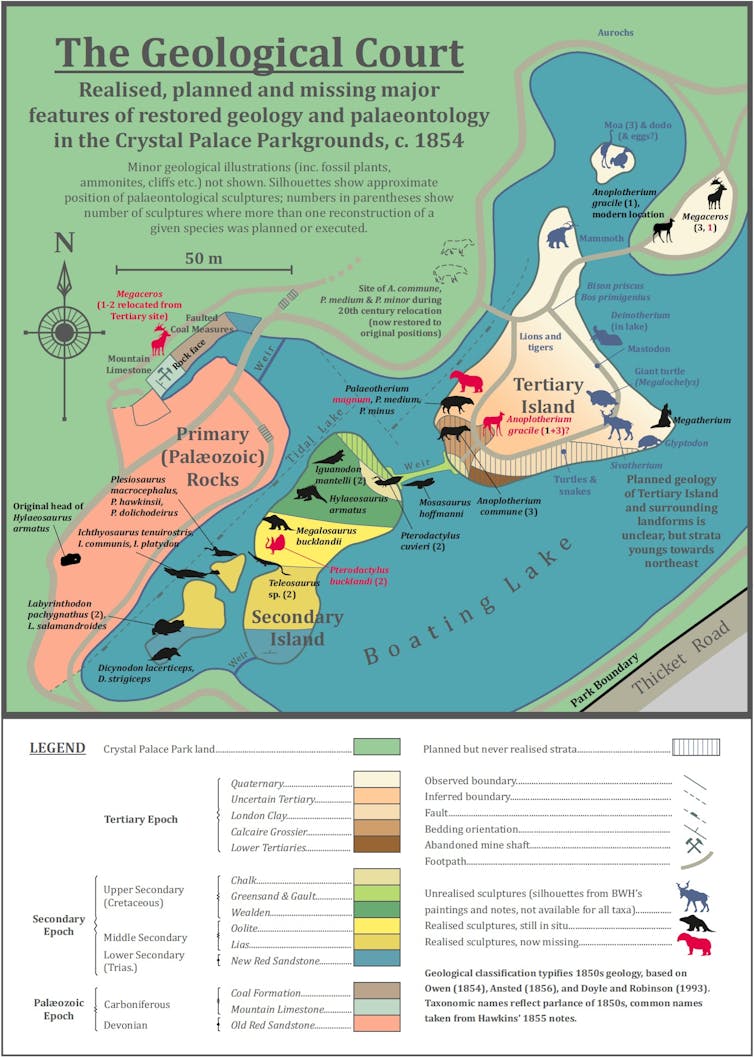

Peer-Reviewed PublicationIMAGE: ON THE LEFT IS A POND VEGETATION CONTROLLED BY HIGH WATER LEVELS AND ON THE RIGHT A DRIER TUNDRA VEGETATION, WHICH IS BECOMING MORE PREVALENT IN AREAS WHERE THE WATER LEVEL IS LOW AND THE SOIL DRIES OUT IN SUMMER. IN AREAS WHERE PERMAFROST DISAPPEARS, NEW STUDIES SHOW THAT THE RELEASE OF METHANE CAN BE REDUCED BY A FACTOR OF 10 DUE TO CHANGES IN HYDROLOGY, PLANT COMMUNITY AND THE COMPOSITION OF MICROORGANISMS IN THE SOIL (PHOTO: BO ELBERLING) view more

CREDIT: PHOTO: BO ELBERLING, UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN.

It is widely understood that thawing permafrost can lead to significant amounts of methane being released. However, new research shows that in some areas, this release of methane could be a tenth of the amount predicted from a thaw. The research was conducted in Sweden by an international group that includes researchers from the University of Copenhagen. A crucial, yet an open question is how much precipitation the future will bring.

A typical landscape in northern Sweden. On the left is a pond vegetation controlled by high water levels and on the right a drier tundra vegetation, which is becoming more prevalent in areas where the water level is low and the soil dries out in summer. In areas where permafrost disappears, new studies show that the release of methane can be reduced by a factor of 10 due to changes in hydrology, plant community and the composition of microorganisms in the soil (photo: Bo Elberling)

Permafrost runs like a frozen belt of soil and sediment around Earth’s northern arctic and sub-arctic tundra. As permafrost thaws, microorganisms are able to break down thousands of years-old accumulations of organic matter. This process releases a number of greenhouse gases. One of the most critical gasses is methane; the same gas emitted by cattle whenever they burp and fart.

Because of this, scientists and public agencies have long feared methane emissions from permafrost to rise in step with global temperatures. But, in some places, it turns out that methane emissions are lower than once presumed.

In a comprehensive new study by a collaborative from the University of Gothenburg, Ecole Polytechnique in France and the Center for Permafrost (CENPERM) at the University of Copenhagen, researchers measured the release of methane from two localities in Northern Sweden. Permafrost disappeared from one of the locations in the 1980’s, and 10-15 years later in the other.

The difference between the two areas shows what can happen as a landscape gradually adapts to the absence of permafrost. The results show that the first area to lose its permafrost now has methane emissions ten times less than in the other locality. This is due to gradual changes in drainage and the spread of new plant species. The study’s findings were recently published in the journal Global Change Biology.

"The study has shown that there isn’t necessarily a large burst of methane as might have been expected in the wake of a thaw. Indeed, in areas with sporadic permafrost, far less methane might be released than expected," says Professor Bo Elberling of CENPERM (Center for Permafrost), at the University of Copenhagen’s Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management.

Water, plants and microbes all play a role

According to Professor Elberling, water drainage accounts for why far less methane was released than anticipated. As layers of permafrost a few meters deep begin to disappear, water in the soil above begins to drain.

"Permafrost acts somewhat like the bottom of a bathtub. When it melts, it's as if the plug has been pulled, which allows water to seep through the now-thawed soil. Drainage allows for new plant species to establish themselves, plants that are better adapted for drier soil conditions. This is exactly what we’re seeing at these locations in Sweden," he explains.

Grasses typical of very wet areas with sporadic permafrost have developed a straw-like system that transports oxygen from their stems down into to their roots. These straws also act as a conduit through which methane in the soil quickly find its way to the surface and thereafter into the atmosphere.

As the water disappears, so do these grasses. Gradually, they are replaced by new plant species, which, due to the dry soil conditions, do not need transport oxygen from the surface via their roots. The combination of more oxygen in the soil and reduced methane transport means that less methane is produced and that the methane that is produced can be better converted to CO2 within the soil.

"As grasses are outcompeted by new plants like dwarf shrubs, willows and birch, the transport mechanism disappears, allowing methane to escape quickly up through soil and into the atmosphere," explains Bo Elberling.

The combination of dry soil and new plant growth also creates more favorable conditions for soil bacteria that help break methane down.

"When methane can no longer escape through the straws, soil bacteria have more time to break it down and convert it into CO2," Bo Elberling elaborates.

As a result, one can imagine that as microorganisms reduce methane emissions, the process will lead to more CO2 being released. Yet, no significant increase in CO2 emissions was observed by the researchers in their study. This is interpreted as being the result of the CO2 balance, which is more heavily determined by plant roots than the CO2 released from the microorganisms that break down methane. Crucially, even though methane ends up as CO2, it is considered less critical in climate change context as methane is at least 25 more potent greenhouse gas as compared to CO2.

Infobox

Areas of sporadic permafrost cover the southern part of the Arctic around the globe, where the temperature is typically between minus five and zero degrees. This means that a rise in temperature can cause the permafrost to completely disappear.

Future precipitation will be decisive

According to Professor Elberling, the future’s greatest unknown is the amount of future precipitation. Because, while thawing permafrost makes it easier for soil to drain in areas with sporadic permafrost, increased rainfall or poor drainage can prevent an area from drying. Where the latter is the case, we shouldn’t expect a corresponding drying out and reduction in methane being released.

"The balance between precipitation and evaporation will be crucial for the release and absorption of greenhouse gases. However, predicting Arctic precipitation is fraught with uncertainty. In some areas we’re seeing increased precipitation, while in others, things are drying out - especially in the summer," says Elberling.

The study focuses on data from two localities in northern Sweden. As such, Professor Elberling is cautious about concluding that analogous conditions extend to other areas with similar permafrost, such as in Canada or Russia.

The study contributes to a new understanding of a process that must be taken into account whenever future methane emissions are assessed in permafrost-affected areas.

"In their most recent report on the Arctic’s future methane budget, the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) has not considered the conditions highlighted by us in the study. Our study reverses the general perception that thawed permafrost is to be consistently associated with increased levels of methane being released," Professor Elberling concludes.

Lead author Mats Björkman from University of Göteborg adds:

“Our research shows that methane emissions from areas where permafrost thaws are not the same everywhere. The new observations represent an important component of a more comprehensive picture of the climate impact in the Arctic. Our results also underscore the importance of including hydrological, vegetation, and microbial changes when studying the long-term effects of permafrost thawing and disappearing.”

In the future Mats Björkman wants to determine which areas will either get wetter or drier and see how they are affected when the permafrost thaws.

JOURNAL

Global Change Biology

ARTICLE TITLE

Reduced methane emissions in former permafrost soils driven by vegetation and microbial changes following drainage