Dobbs v Jackson and South African womxn’s fast-disappearing right to access abortion services

South African womxn, in their diversity, have a constitutionally recognised right to bodily autonomy, and to make decisions about their sexual and reproductive health. (Photo: csvr.org.za / Wikipedia)

MAVERICK CITIZEN

BODILY RIGHTS OP-ED

By Charlene May and Khuliso Managa

BODILY RIGHTS OP-ED

By Charlene May and Khuliso Managa

31 May 2022 0

Womxn have the right to an abortion in South Africa, which is protected by the Constitution. Yet, of the 3,880 health facilities in South Africa, less than 7% provide access to abortion services, and of the 505 facilities specifically designated to provide the services, only an estimated 197 are operational.

On 2 May 2022, Politico, a US news organisation, published a leaked draft of the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization, a case referred from Mississippi, that would overturn Roe v Wade and Planned Parenthood v Casey and eliminate the US federal standard on abortion access.

Over the past few weeks, the Women’s Legal Centre has received requests for comment and input on this draft opinion prepared by US Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito.

In essence, if the draft opinion is adopted officially, and the decisions in Roe v Wade and Planned Parenthood v Casey are overturned, the right to abortion in America would need to be decided from state to state.

So, what will this mean for South Africans?

A good start is to note that our legal governance system is vastly different from that of the US. There will therefore be very little direct consequences from the American decision on South African law – a decision that, based on the draft opinion, appears to be inevitable.

However, our society, and thus our law processes and policies, are still not completely insulated from the influence of what happens in the world around us. American culture, of course, has an impact on what happens in the world, and its shift towards upholding and enforcing conservative, discriminatory views.

The impact overturning Roe v Wade and Planned Parenthood v Casey will have on the South African womxn’s right to abortion

The current South African Legal Framework:

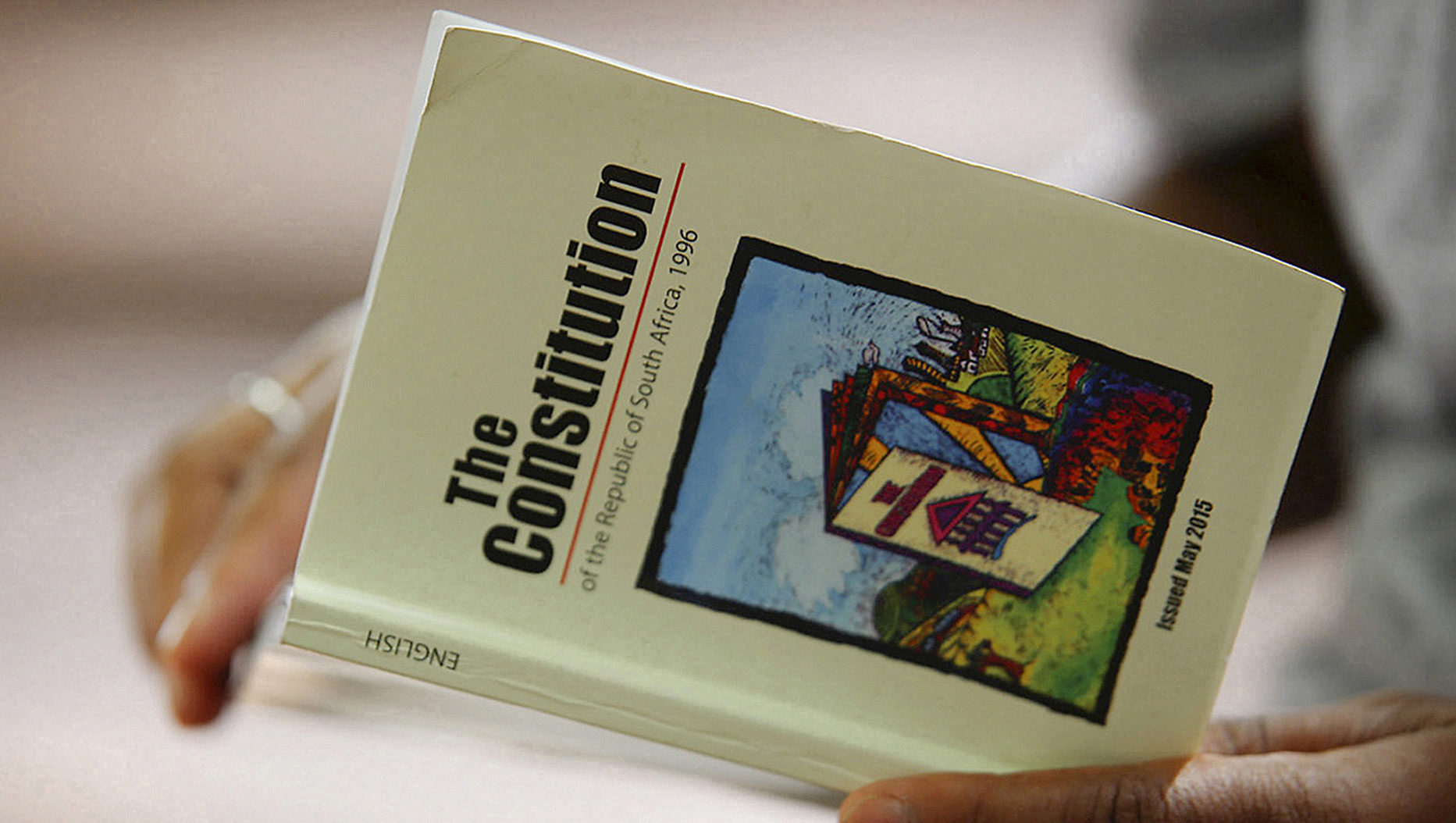

South African womxn, in their diversity, have a constitutionally recognised right to bodily autonomy, and to make decisions about their sexual and reproductive health.

Abortions are legal in South Africa but many people still die as a result of unsafe terminations

(Photo: plannedparenthoodaction.org / Wikipedia)

Freedom of choice, and the ability to make decisions based on one’s own circumstances, is a golden thread that runs through our Constitution and is guaranteed in section 12. This section provides for the right to freedom and security of the person, and section 12(2) specifically provides for the right to bodily and psychological integrity, which includes the right to make decisions concerning reproduction; and the right to security in and control over one’s body. These rights contained in sections 12(2)(a) and (b) expressly recognise and protect the right for one to make decisions in relation to reproduction, including the right to termination of pregnancy.

These rights are also strengthened by the protections of the rights to reproductive healthcare (section 27(1)(a)), the right to equality (section 9); the right to dignity (section 10); and the right to privacy (section 14).

To support the realisation of these rights, the Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act 92 of 1996 (CTOPA), was adopted. It regulates when, where and from whom womxn can access the right to terminate a pregnancy when they choose to do so.

Accordingly, from a formal equality perspective, our rights as womxn are strongly entrenched and secured within a legal framework, underpinned by the Constitution. Of far greater concern is the actual realisation of these rights and their enjoyment by the womxn who hold them. The issue is therefore whether it truly is accessible to the everyday womxn, if and when she should need it.

The practical accessibility of the right to abortion in South Africa

As part of the work done by the Women’s Legal Centre, we have, since the adoption of the CTOPA, been monitoring its implementation and have noted that a failing public healthcare system and a lack of political will are the main contributors to multiple intersecting barriers that prevent or hinder womxn’s access to abortion services.

Freedom of choice, and the ability to make decisions based on one’s own circumstances, is a golden thread that runs through our Constitution and is guaranteed in section 12. This section provides for the right to freedom and security of the person, and section 12(2) specifically provides for the right to bodily and psychological integrity, which includes the right to make decisions concerning reproduction; and the right to security in and control over one’s body. These rights contained in sections 12(2)(a) and (b) expressly recognise and protect the right for one to make decisions in relation to reproduction, including the right to termination of pregnancy.

These rights are also strengthened by the protections of the rights to reproductive healthcare (section 27(1)(a)), the right to equality (section 9); the right to dignity (section 10); and the right to privacy (section 14).

To support the realisation of these rights, the Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act 92 of 1996 (CTOPA), was adopted. It regulates when, where and from whom womxn can access the right to terminate a pregnancy when they choose to do so.

Accordingly, from a formal equality perspective, our rights as womxn are strongly entrenched and secured within a legal framework, underpinned by the Constitution. Of far greater concern is the actual realisation of these rights and their enjoyment by the womxn who hold them. The issue is therefore whether it truly is accessible to the everyday womxn, if and when she should need it.

The practical accessibility of the right to abortion in South Africa

As part of the work done by the Women’s Legal Centre, we have, since the adoption of the CTOPA, been monitoring its implementation and have noted that a failing public healthcare system and a lack of political will are the main contributors to multiple intersecting barriers that prevent or hinder womxn’s access to abortion services.

Women have a right to an abortion in South Africa, which is protected by the Constitution. Yet, of the 3,880 health facilities in South Africa, less than 7% provide access to abortion services, and of the 505 facilities specifically designated to provide the services, only an estimated 197 are operational. (Photo: coe.int / Wikipedia)

South Africa’s failing healthcare system is of great concern in terms of access. The Covid-19 pandemic and ensuing health crises have placed additional pressure on the substandard state of healthcare. It is of little surprise to womxn that reproductive health rights have been relegated to the bottom of the list of priorities.

With these rights not being a priority to the state, more and more of the public designated abortion facilities have become dysfunctional. Issues related to staff and resource shortages have very quietly led to the effective closure of these facilities and womxn in more rural and remote areas are being left without the ability to exercise the right to choose.

Of the 3,880 health facilities in South Africa, less than 7% provide access to abortion services, and of the 505 facilities specifically designated to provide the service, only an estimated 197 are operational. These statistics predate the Covid-19 pandemic.

The issues above contribute to an environment where womxn face additional barriers, including a lack of information on basic things such as where to obtain free abortion services and what to expect in this process. Womxn also face active obstructors such as hospital and clinic staff who refuse to provide these services, or who actively misdirect or confuse womxn about information essential for them to exercise their rights.

A rise in conservative anti-rights efforts to obstruct womxn’s access to rights has also sprung up in the form of pregnancy crisis centres. These centres present as access points for information and services, but instead spread misinformation and enforce harmful stereotypes and fear. These all contribute to deterring womxn from accessing abortion services.

South Africa’s failing healthcare system is of great concern in terms of access. The Covid-19 pandemic and ensuing health crises have placed additional pressure on the substandard state of healthcare. It is of little surprise to womxn that reproductive health rights have been relegated to the bottom of the list of priorities.

With these rights not being a priority to the state, more and more of the public designated abortion facilities have become dysfunctional. Issues related to staff and resource shortages have very quietly led to the effective closure of these facilities and womxn in more rural and remote areas are being left without the ability to exercise the right to choose.

Of the 3,880 health facilities in South Africa, less than 7% provide access to abortion services, and of the 505 facilities specifically designated to provide the service, only an estimated 197 are operational. These statistics predate the Covid-19 pandemic.

The issues above contribute to an environment where womxn face additional barriers, including a lack of information on basic things such as where to obtain free abortion services and what to expect in this process. Womxn also face active obstructors such as hospital and clinic staff who refuse to provide these services, or who actively misdirect or confuse womxn about information essential for them to exercise their rights.

A rise in conservative anti-rights efforts to obstruct womxn’s access to rights has also sprung up in the form of pregnancy crisis centres. These centres present as access points for information and services, but instead spread misinformation and enforce harmful stereotypes and fear. These all contribute to deterring womxn from accessing abortion services.

Section 12 of the Constitution provides for the right to freedom and security of the person, and section 12(2) specifically provides for the right to bodily and psychological integrity, which includes the right to make decisions concerning reproduction; and the right to security in and control over one’s body. (Photo: Leila Dougan)

Compounding these barriers, in 2020 the Department of Health released the National Clinical Guideline on the Implementation of the Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act which makes a provision for healthcare providers to refuse to provide abortion services on the basis of “conscientious objection”. A provision that is not aligned with the CTOPA and that has the effect of again limiting where and from whom womxn can access their right to abortions. This is again of particular concern when designated facilities are already understaffed and underresourced, if not closed entirely.

Compounding these barriers, in 2020 the Department of Health released the National Clinical Guideline on the Implementation of the Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act which makes a provision for healthcare providers to refuse to provide abortion services on the basis of “conscientious objection”. A provision that is not aligned with the CTOPA and that has the effect of again limiting where and from whom womxn can access their right to abortions. This is again of particular concern when designated facilities are already understaffed and underresourced, if not closed entirely.

Issues related to staff and resource shortages have very quietly led to the effective closure of designated abortion facilities and womxn in more rural and remote areas are being left without the ability to exercise the right to choose. (Photo: EPA / Jon Hrusa)

These barriers also feed into an ever-growing illegal abortion service industry which runs rampant in a country where, in practice, womxn should not have to look outside the legal framework to exercise their right to choose.

Although the US case will have no direct implications on our legal framework, and our rights to abortion, it most certainly will contribute to the ever-growing list of barriers that womxn face in their lived realities.

These barriers also feed into an ever-growing illegal abortion service industry which runs rampant in a country where, in practice, womxn should not have to look outside the legal framework to exercise their right to choose.

Although the US case will have no direct implications on our legal framework, and our rights to abortion, it most certainly will contribute to the ever-growing list of barriers that womxn face in their lived realities.

So, what will the impact be?

Whenever conservative anti-rights rhetoric grows through anticipated victories, such as this draft opinion in the US, the impact is felt here in South Africa and across the globe. Harmful and discriminatory language about womxn who access abortion services, their bodily autonomy and how they are viewed in society enjoys greater prominence and acceptance in a society that upholds patriarchy. And as a country deeply rooted in patriarchal practices and views, we increasingly see the impact of rights denial and rejection.

As mentioned before, the stigma surrounding abortion is still an enormous challenge to South African womxn, and to making reproductive health rights a priority for our government.

Accordingly, the overruling of Roe v Wade, in the South African context, will be like adding fuel to a fire that has been quietly burning away womxn’s rights in South Africa. It legitimises patriarchal stereotypes of womxn in their diversity, entrenches stigmas that weigh down abortion rights, and will only serve to encourage the conservative anti-rights actors, resulting in more legal challenges to our abortion regulations in our courts and more efforts on the ground to frustrate access to existing abortion services. DM/MC

Charlene May and Khuliso Managa are attorneys at the Women’s Legal Centre. It is an African feminist legal centre that advances womxn’s rights and equality using tools such as litigation, advocacy, education, advice, research and training.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/KWRZ632PC5HETLF6JQK6YAYNEE.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/WTJ3H7APTVFI3AZZBL5H2LWJXE.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/A5725LKOPRDTNHZ2ZA2WRMRUWU.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/6Q3RW2E5PFGSZDOV6IB6N7NA3I.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/Y7FFR2WE65HOXKMZMPEEZCNNIM.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/LGABPNPXCRBN5MVDO2JWP3XOYA.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/757YZDDBOVGMDKIDSZMEWVQZYQ.jpg)