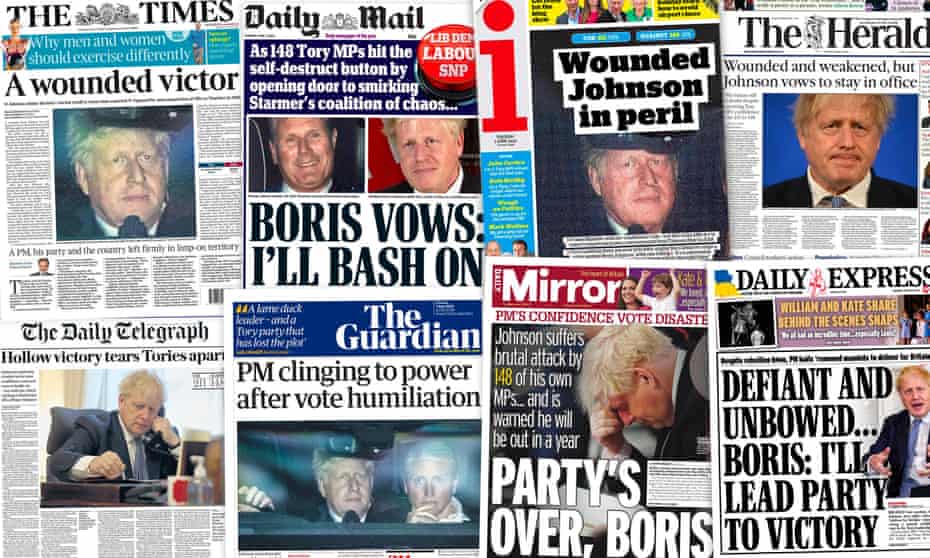

‘Out in a year’: what the papers say about Tory vote on Boris Johnson

Only the most stridently supportive titles stand vocally behind prime minister after 41% of his own MPs vote for his removal

A haunted-looking Boris Johnson stares out from the front pages of many of the papers after a dramatic night of Conservative party bloodletting at Westminster.

The prime minister is shown being driven back from the Commons to Downing Street after he won a Tory no-confidence vote in his leadership by 211 to 148.

Although he called the victory decisive and vowed to “bash on” in government, the reaction of some Tory-supporting newspapers suggests he will not be able to draw a line under his Partygate woes any time soon.

“A wounded victor”, says the Times, alongside the picture of Johnson that seems eerily similar to the famous one of Margaret Thatcher being driven away from Downing Street after she was ousted in a Tory party coup.

The paper adds that it was a worse than expected result for Johnson and throws up another parallel with Thatcher by noting that the same proportion of MPs voted against her as against her current scandal-plagued successor. She resigned two days later.

The Daily Telegraph’s front page headline says “Hollow victory tears Tories apart” and carries a secondary headline saying Johnson’s authority has been “crushed” as rebels circle to finish him off.

The Financial Times also suggests that the prime minister is badly damaged by the vote with its lead headline saying “Johnson wounded in confidence vote as 41% of Tory MPs rebel”.The paper’s columnists line up to give a damning verdict on Johnson’s prospects for leading the party into the future with Tim Stanley declaring simply: “The PM is toast.”

The Mirror proclaims “Party’s over, Boris” and says that the prime minister has suffered a “brutal attack” by his own side “and is warned that he will be out in a year”.

The Guardian’s splash says “PM clinging to power after vote humiliation”, with columnist Martin Kettle writing: “He is irreparably damaged. Politicians don’t recover from such things.”

The i’s front page says “Wounded Johnson in peril” and inside its political editor, Paul Waugh, says Johnson is the “sick man of Downing Street, infecting all those around him”.

The Metro also thinks it’s time for Johnson to go: “The party is over Boris”.

However, the prime minister still has some defiant backing from his cheerleaders in the national papers. Reflecting the concern of some Tories that dumping Johnson is electoral suicide, the Mail has mocked up a red button marked “Lib Dems Labour SNP” and says “MPs hit the self-destruct button by opening door to smirking Starmer’s coalition of chaos”. Underneath, its main headline says “Boris vows: I’ll bash on”.

The Express also tries to strike an upbeat note with

a headline which reads:

“Defiant and unbowed … Boris: I’ll lead party to victory”.

The Sun’s splash is “Night of the blond knives”,

saying that Johnson has been “stabbed in the back by 148 MPs”.

In Scotland the Herald says “Wounded and weakened,

but Johnson vows to stay in office”, while the Press and Journal

says “Boris body blow despite winning confidence vote”.

The Record opts to throw Johnson’s election-winning slogan

back at him with its front page headline: “Get Borexit done”

The Northern Echo says “Carry on Boris (for now)“,

while the Newcastle Journal asks “Is he on his way out?”.

A woman removes invasive cactus plants in Laikipia County, Kenya. Photograph: Peter Muiruri

A woman removes invasive cactus plants in Laikipia County, Kenya. Photograph: Peter Muiruri