ECOCIDE

Dead rivers: The cost of Bangladesh's garment-driven economic boom

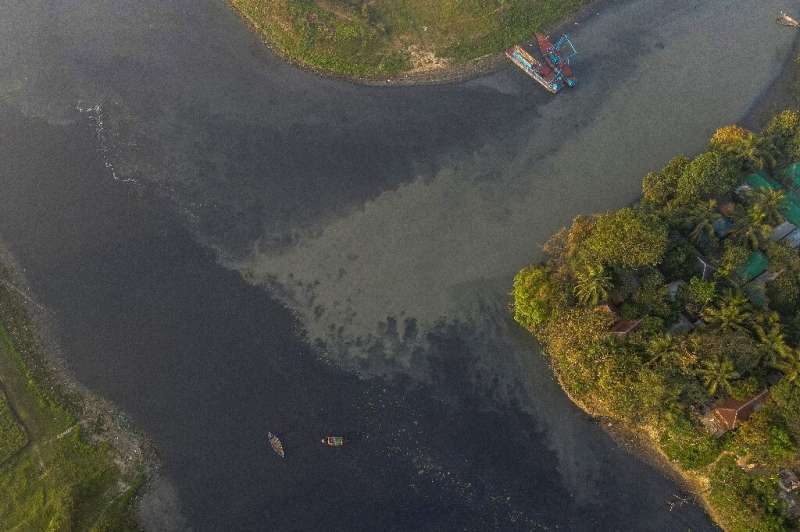

Bangladeshi ferryman Kalu Molla began working on the Buriganga river before the patchwork of slums on its banks gave way to garment factories—and before its waters turned pitch black.

The 52-year-old has a constant cough, allergies and skin rashes, and doctors have told him the vile-smelling sludge that has also wiped out marine life in one of Dhaka's main waterways is to blame.

"Doctors told me to leave this job and leave the river. But how is that possible?" Molla told AFP near his home on the industrial outskirts of the capital Dhaka. "Ferrying people is my bread and butter."

In the half-century since a devastating independence war left its people facing starvation, Bangladesh has emerged as an often unheralded economic success story.

The South Asian country of 169 million has overtaken its neighbour India in per capita income and will soon graduate from the United Nations' list of the world's least developed countries.

Underpinning years of runaway growth is the booming garment trade, servicing global fast-fashion powerhouses, employing millions of women and accounting for around 80 percent of the country's $50 billion annual exports.

But environmentalists say the growth has come at an incalculable cost, with a toxic melange of dyes, tanning acids and other dangerous chemicals making their way into the water.

Bangladesh's capital Dhaka was founded on the banks of the Buriganga more than 400 years ago by the Mughal empire.

"It is now the largest sewer of the country," said Sheikh Rokon, the head of the Riverine People environmental rights group.

"For centuries people built their homes on its banks to bask in the river breeze," he added. "Now the smell of toxic sludge during winter is so horrible that people have to hold their noses as they come near it."

Water samples from the river found chromium and cadmium levels over six times the World Health Organization's recommended maximums, according to a 2020 paper by the Bangladeshi government's River Research Institute.

Both elements are used in leather tanning and excessive exposure to either is extremely hazardous to human health: chromium is carcinogenic, and chronic cadmium exposure causes lung damage, kidney disease and premature births.

Ammonia, phenol and other byproducts of fabric dyeing have also helped to starve the river of the oxygen needed to sustain marine life.

'They are powerful people'

In Shyampur, one of several sprawling industrial districts around Dhaka, locals told AFP that at least 300 local factories were discharging untreated wastewater into the Buriganga river.

Residents say they have given up complaining about the putrid smell of the water, knowing that offending businesses are easily able to shirk responsibility.

"The factories bribe (authorities) to buy the silence of the regulators," said Chan Mia, who lives in the area.

"If someone wants (to) raise the issue to the factories, they'd beat them up. They are powerful people with connections."

The crucial position of the textile trade in the economy has created a nexus between business owners and the country's political establishment. In some cases, politicians themselves have become powerful industry players.

Further south, in Narayanganj district, residents showed AFP a stream of crimson-coloured water draining into stagnant canals from a nearby factory.

"But you cannot say a word about it loudly," an area resident told AFP, speaking on condition of anonymity. "We only suffer in silence."

The Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA), which represents the interests of around 3,500 top factories, defends its record by pointing out the environmental certifications given out to its members.

"We are going green—that's why we are witnessing big jumps in export orders," BGMEA president Faruque Hassan told a recent press conference.

But smaller factories and sub-contractors operating on the industry's razor thin margins say they are unable to afford the cost of wastewater treatment.

A top garment official in the Savar industrial district, speaking to AFP on condition of anonymity, said even most high-end factories serving major US and European brands often do not turn on their treatment machinery.

"Not everyone regularly uses it. They want to save costs," he said.

'Facing the same fate'

Bangladesh is a delta country criss-crossed by more than 200 waterways, each of them connected to the mighty Ganges and Brahmatura rivers that course from the Himalayas and through the South Asian subcontinent.

More than a quarter of them are now heavily contaminated with industrial pollutants and need to be "urgently" saved, said an April legal notice sent to the government by the Bangladesh Environmental Lawyers Association (BELA).

Authorities have established a commission tasked with saving key water bodies, upon which close to half the country's population depend for farming, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization.

The National River Commission has launched several high profile drives to fine factories found to have polluted rivers.

Its newly appointed chief, Manjur Chowdhury, said "greedy" industrialists were to blame for the state of the country's waterways.

But he also admitted that the enforcement of existing penalties was inadequate to address the scale of the problem.

"We have to frame new laws to face this emergency situation. But it will take time," he told AFP.

Any action will be too late for the five rivers that circle Dhaka and its industrial outskirts.

All are already technically dead, meaning they are completely devoid of marine life, said prominent environmental activist Sharif Jamil.

"With factories now moving deep into the rural heartland, rivers across the country are facing the same fate," he told AFP.

© 2022 AFP

![Map of the Dampier Archipelago (Murujuga) showing locations of areas mentioned in the text. (Contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data [2020] processed by Sentinel Hub). Credit: <i>Geoarchaeology</i> (2022). DOI: 10.1002/gea.21917 Australia's first marine Aboriginal archaeological site questioned](https://scx1.b-cdn.net/csz/news/800a/2022/australias-first-marin.jpg)