FULL STORY

In a new comprehensive literature review, researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy's National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) discovered that alternatives to recycling may have untapped potential to build an effective circular economy for solar photovoltaic (PV) and battery technologies. These alternative strategies, such as reducing the use of virgin materials in manufacturing, reusing for new applications, and extending product life spans, may provide new paths to building sustainable product life cycles.

These insights come after an analysis of more than 3,000 scientific publications exploring the life cycle of the most common PV and lithium-ion battery technologies, including starting materials, environmental impacts, and end-of-life options. The NREL researchers examined 10 possible pathways toward a circular economy. The findings highlight key insights, gaps, and opportunities for research and implementation of a circular economy for PV and battery technologies, including strategies that are currently being underutilized.

Demand for PV panels and lithium-ion batteries is expected to increase as the United States shifts away from fossil fuels and deploys more clean energy. Creating a robust circular economy for these technologies could mitigate demand for starting materials and reduce waste and environmental impacts. Circular economy strategies also have the potential to create clean energy jobs and address environmental justice concerns.

The researchers noted the emphasis on recycling may overlook the challenges and opportunities that research into other strategies could reveal. "If you can keep them as a working product for longer, that's better than deconstructing it all the way down to the elements that occurs during recycling," said Garvin Heath, senior environmental scientist and energy analyst and Distinguished Member of Research Staff at NREL. "And when a product does reach the end of its life, recycling is not the only option."

The deconstruction process takes more energy and generates more associated greenhouse gas emissions to then build into another product than keeping the first product in use longer, he said. Heath, along with his NREL colleague Dwarakanath Ravikumar, are lead authors of the 52nd annual Critical Review of the Air & Waste Management Association, titled "A Critical Review of Circular Economy for Lithium-Ion Batteries and Photovoltaic Modules -- Status, Challenges, and Opportunities," which appears in the June edition of the Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association.

Their co-authors, also from NREL, are Brianna Hansen and Elaine Kupets.

"People often summarize the product life cycle as 'take, make, waste.'" Heath said. "Recycling has received a lot of attention because it addresses the waste part, but there are ways to support a circular economy in the take part and the make part, too."

Recycling to recover the materials used in the technologies is preferable to discarding them in a landfill, he said, "but if we can think about designing a product to use less materials to begin with, or less hazardous materials, that should be the first strategy."

The authors also noted that challenges remain in developing PV and battery recycling methods. There are currently no integrated recycling processes that can recover all the materials for either technology, and existing research has focused more on lab-scale methods.

NREL is already leading efforts to improve PV reliability, extend PV life spans, reduce the use of hazardous materials, and decrease demand for starting materials. This includes leading the Durable Module Materials Consortium (DuraMAT), which is researching ways to extend the useful life of PV modules, and the Bio-Optimized Technologies to keep Thermoplastics out of Landfills and the Environment (BOTTLE) Consortium, which is developing ways to improve the recycling of plastics.

NREL is also a partner in the Argonne National Laboratory-led consortium ReCell, which works with industry, academia, and national laboratories to advance recycling technologies along the entire battery life cycle for current and future battery chemistries.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Advanced Manufacturing Office and Solar Energy Technologies Office funded the research.

Journal Reference:Garvin A. Heath, Dwarakanath Ravikumar, Brianna Hansen, Elaine Kupets. A critical review of the circular economy for lithium-ion batteries and photovoltaic modules – status, challenges, and opportunities. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association, 2022; 72 (6): 478 DOI: 10.1080/10962247.2022.2068878

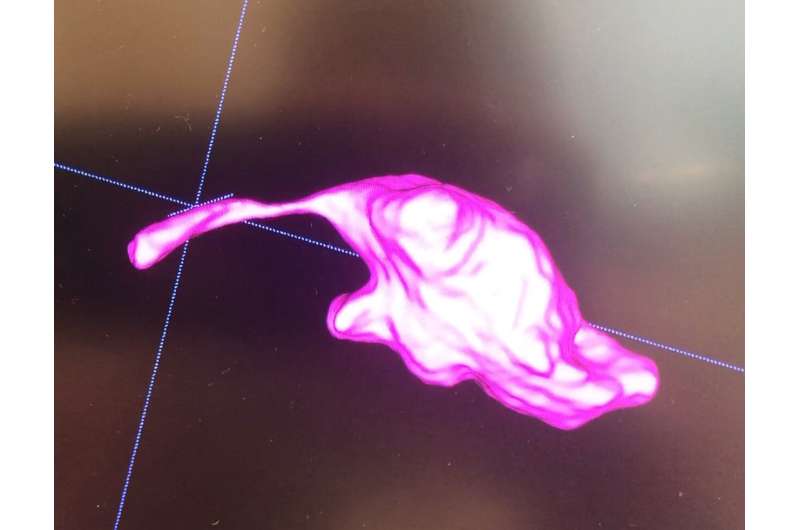

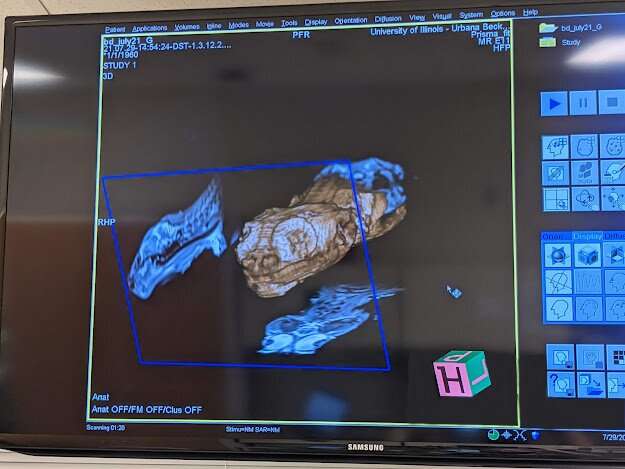

Interdisciplinary researchers at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign performed MRI scans on bearded dragons, like the one shown here, to generate a first-of-its-kind brain atlas: a high-resolution map of regions in the creatures' brains.

Interdisciplinary researchers at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign performed MRI scans on bearded dragons, like the one shown here, to generate a first-of-its-kind brain atlas: a high-resolution map of regions in the creatures' brains.