(Image courtesy of DeepGreen.)

In 1983, Verena Tunnicliffe was floating about 250 kilometres off the coast of Vancouver Island when a call came over the radio — geologists on a nearby sister ship had dredged up something strange from the sea floor.

“We got all these strange smelly worms,” Tunnicliffe remembers them saying. “Would you like them?”

The deep-sea researcher was the only one with a submarine, and a year later, her exploration team had raised enough money to go back.

When Tunnicliffe finally descended over 2,000 metres to a patch of ocean floor, everything was dark, save for the light on the submersible.

Below them, two tectonic plates diverged, allowing cold sea water to seep through the Earth’s crust. Super-heated by molten lava, the water shoots back into the ocean as a 400-degree-Celsius hot soup of nutrients and chemicals.

The crew crept along the bottom in an exercise Tunnicliffe describes as “trying to explore the Rocky Mountains with a flashlight.”

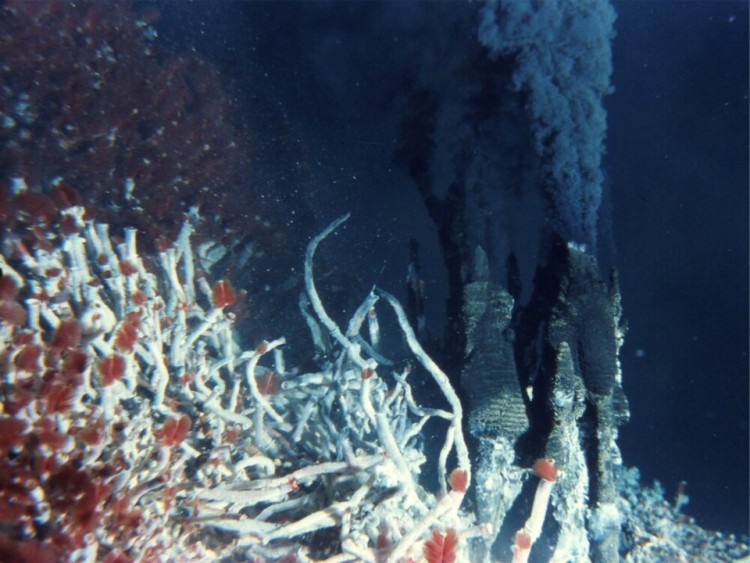

First came white mats of bacteria. Then, out of the darkness, huge mounds of “gorgeous” white tube worms emerged, the metre-and-a-half-long creatures topped with red plumes. Inside, the scientist would later learn they had no guts, but a body filled with vent-fed bacteria that feed the worms.

And in a potential window onto the origin of life on a hot, young Earth, a bacteria found at the B.C. vents was later discovered to survive temperatures of 121 C — the hottest upper limit for life.

“Just covered, dripping with animals,” Tunnicliffe said, pointing to at least 12 distinct species found there and not seen anywhere else on Earth.

A year later, Tunnicliffe would find vents at an enormous scale, hydrothermal openings that form chimneys up to 45 metres tall known as “black smokers.”

In the decades that followed, over 800 extinct and active chimneys would be discovered. The deep-sea scientist would have 10 undersea creatures named after her, and go on to be awarded the Order of Canada for her pioneering work.

Soaring up to the height of buildings, the underwater vents and their chimneys can often contain ore-grade metal deposits of gold, copper and silver — making them an attractive potential source of wealth if only someone could figure out how to mine them.

A vast array of life congregates around ‘black smokers,’ which spew water super-heated to 380 Celsius and form part of the Endeavour Hot Vents, the first such sites to be protected in the world. – Photo by Verena Tunnicliffe

By 2003, the Endeavour Hydrothermal Vents would be the first marine protected area in Canada, and the first “hot vents” protected from human exploitation in the world.

But in other stretches of deep ocean, a battle that had been quietly brewing for decades was about to enter a new phase of heightened tensions, raising the prospect of a race for some of the ocean’s deepest known riches.

At the centre of the controversy sits The Metals Company, a Vancouver-based mining firm looking to harvest the minerals required to wean the world of fossil fuels and on to a more sustainable path.

The U.S. Geological Survey found this year that deep-ocean mines could provide up to 45% of all the world’s critical metal needs by 2065.

But for scientists like Tunnicliffe, a race to the bottom of one of the planet’s least explored realms comes with huge risks, both to its poorly understood ecosystems and their link to an ocean carbon pump that’s thought to scrub 30 per cent of human-produced greenhouse gas emissions from the atmosphere every year.

“We’re talking about a group of organisms that have changed the way we understand life on this planet, all the way back to the origin of life, how life works in highly extreme settings where we never thought any life could live,” said Tunnicliffe.

“It’s fuelled our search for life on other planets.”

Three pots of deep-sea treasure and a Russian sub

The first sign that the ocean floor could hold minerals useful to humanity date back over 150 years to the HMS Challenger expedition, a voyage many now cast as the foundation of modern oceanography.

The expedition would be the first to probe the Mariana Trench with bathymetric soundings and verify the existence of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the longest mountain range in the world and the separation line where two crustal plates diverge, expanding the Atlantic’s sea floor.

But it was on March 7, 1873, when crew from the expedition dredged on deck “several peculiar black oval bodies which were composed of almost pure manganese oxide” that humanity got its first look at what wealth lay deep out of sight.

The metallic masses start with a core — a sunken shark tooth, tiny fossil or piece of basalt rock. Over tens of millions of years, minerals precipitate out of the surrounding sea water, forming one metallic layer after another.

Often growing to the size of a potato, the nodules are rich in nickel, copper, cobalt and manganese — all metals highly sought after by battery makers and other technology manufacturers.

Drop down 4,000 metres below parts of the Pacific Ocean, and they can be found scattered across the surface of abyssal plains, flat stretches of relatively unexplored ocean that cover roughly half the surface of the Earth.

But like the precious metals found near some hydrothermal vents, in the past, it was either too expensive or the technology didn’t exist to pull the nodules from the deep.

It would take more than 90 years before the idea of mining the metallic nodules would once again capture the public’s attention.

In 1965, mining engineer John L. Mero published the influential book “The Mineral Resources of the Sea,” sparking wide interest in the nodules at the time when they were thought to be an infinite resource growing faster than they could be harvested.

A year later, Malta’s ambassador to the United Nations, Arvid Pardo, made an impassioned plea to the General Assembly calling on coastal states to end the expansion of exclusive economic zones and regulate the ocean floor, not only for “those who possess the required technology,” but “in the interest of mankind.”

“That’s where the idea came that whatever we find out there really belongs to everyone, and that it needs also to be fostered for the future generations,” said Tunnicliffe.

The question revolved around the idea that the ocean’s riches shouldn’t just belong to the wealthiest nations with the resources to exploit the sea floor. That set off a multi-decadal legal process to regulate mining under international waters.

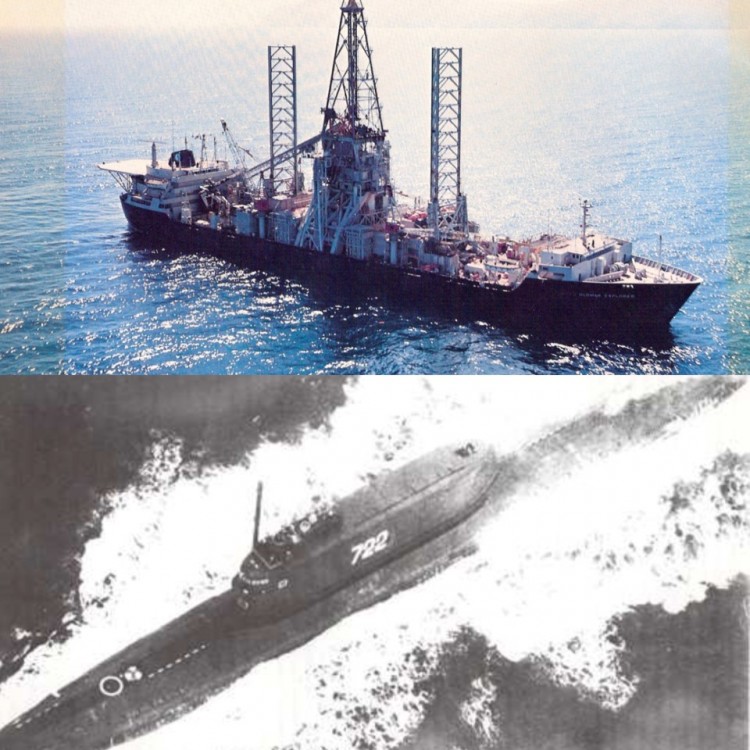

But the pendulum would continue to swing and in the early 1970s, a commodity boom drove further interest in deep-sea mining. So when eccentric billionaire Howard Hughes announced he was building a giant ship to mine the ocean’s abyss, the story was plausible.

To the public, the expedition would be the first attempt to mine the deep sea’s metal nodules. In reality, it was an elaborate ruse.

In 1968, U.S. authorities had learned Soviet submarine K-129 had sunk in over 5,000 metres of water, roughly 2,500 kilometres northwest of Hawaii.

Working with Hughes and his new Glomar Explorer ship, the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency planned to recover the submarine and its nuclear-tipped torpedoes.

In 1975, reporting by the Los Angeles Times and later The New York Times would reveal the outline of what some have described as “the most daring covert operation in history.”

The story has shifted throughout the years, some suggesting most of the submarine was recovered, others stating that it broke up as it was pulled from the depths to the ship’s moon pool.

Whatever the case, the extraordinary stories that emerged from what was declassified as Project Azorian in 2010, also helped set off a reckoning over who should have access to the deep — and in particular, the riches sitting on its abyssal floor.

A half-dozen competing international consortia would begin piloting deep-sea mining in the late 1970s. But by the early 1980s, commodity prices dropped and that work was shelved as companies cut back their research budgets. As German historian Ole Sparenberg put it, deep-sea mining was essentially “dead in the water.”

Concerns over the environment and equity for less wealthy nations eventually led the United Nations to draw up the International Seabed Authority — also known as the ISA or ‘the Enterprise’ — in 1982 under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), and ratify its existence in a 1994 implementation agreement.

Today, the Jamaica-based body is made up of 167 member nations and the European Commission.

A custodian of the deep sea as a “common heritage for mankind,” the ISA’s dual mandate is to facilitate the extraction of mineral resources from the seabed, while at the same time protecting the deep-sea environment.

The prevailing sentiment at the time was that land-based mining was much more profitable, “and how are you gonna do this anyway?” said Tunnicliffe.

Even if the technology and financing were there to pull the metals from the deep, no regulations existed to allow for mining in international waters.

That is until an ambitious company from Vancouver, B.C., triggered a countdown that could open the floodgates for deep-sea mining and prompt a new age of resource exploitation.

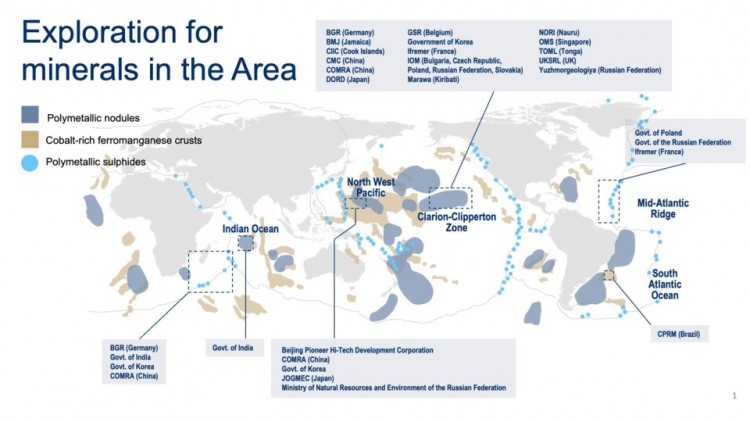

Areas of the sea floor under exploration contracts with the International Seabed Authority. Image from ISA

Areas of the sea floor under exploration contracts with the International Seabed Authority. Image from ISAHalfway through a two-year countdown

On an overcast day in June 2022, a handful of activists, scientists and artists dedicated to sea life unfurled an ocean-blue banner and took aim at The Metals Company, whose headquarters sits in a nondescript Vancouver office tower five blocks away.

“Imagine house-sized machines crawling along the seabed and indiscriminately vacuuming up the contents,” said Michelle Connolly, an ecologist who travelled 10 hours from Prince George to help lead the rally near the city’s seawall.

Through its wholly owned subsidiary, Nauru Ocean Resources, The Metals Company has an exploratory licence covering four areas in the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone — a nodule-rich area halfway between Hawaii and Mexico where the company is looking to explore nearly 75,000 square kilometres of sea bed.

That contract is among 31 the ISA has handed out since 2001, when the price of metals began to surge again.

Until 2010, the international body largely granted contracts to national agencies. But as the price of metals climbed and technology developed, several companies have looked to get in the race.

“If you remember, that was when people were going around knocking down copper statues and stealing copper wires,” said Tunnicliffe. “That’s what suddenly turned back to looking at the deep sea.”

Nineteen different companies have sought exploration contracts to probe abyssal plains for the polymetallic nodules.

Another seven contracts have been granted to companies looking to mine hydrothermal mineral deposits around hot vents.

And in a third target for submarine mining, the ISA has approved five exploration contracts for underwater mountain ranges known as seamounts, where underwater peaks and ridges are at times covered in crusts of cobalt, platinum, manganese and rare earth metals — a multi-million-year process of accretion deposited like a 30-centimetre-thick cap of black snow.

A ‘goblet’ glass sponge up to a metre high rises above a metallic nodule field 2,570 metres below the surface near Johnston Atoll in the Pacific Ocean. Credit: NOAA

A ‘goblet’ glass sponge up to a metre high rises above a metallic nodule field 2,570 metres below the surface near Johnston Atoll in the Pacific Ocean. Credit: NOAAAll of those contracts are exploratory and none of them include provisions to carry out industrial-scale mining, largely because the ISA has not yet written the rules of the road.

That changed in June 2021, when the small island nation of Nauru, acting as a sponsor of Nauru Ocean Resources, approached the ISA, requesting it establish a set of regulations that would govern how companies could mine the deep.

Through an obscure clause, which set off a two-year countdown under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, ISA must finalize a set of regulations.

A final decision is expected to be released in July 2023, according to Tunnicliffe, who in the past, led a mining working group at the ISA, providing expert scientific advice to help draft anticipated regulations around deep-sea mining.

Applications to commercially mine the seabed will still have to be approved on a case-by-case basis, with each one requiring an environmental review process, said the scientist.

“But at that point,” she said. “The inevitability is there.”

Ecologist Michelle Connolly attends a rally against deep-sea mining in Vancouver, B.C., five blocks from The Metals Company’s offices. Credit: Stefan Labbe/Glacier Media.

Ecologist Michelle Connolly attends a rally against deep-sea mining in Vancouver, B.C., five blocks from The Metals Company’s offices. Credit: Stefan Labbe/Glacier Media.

.png)