Reuters | July 4, 2022 |

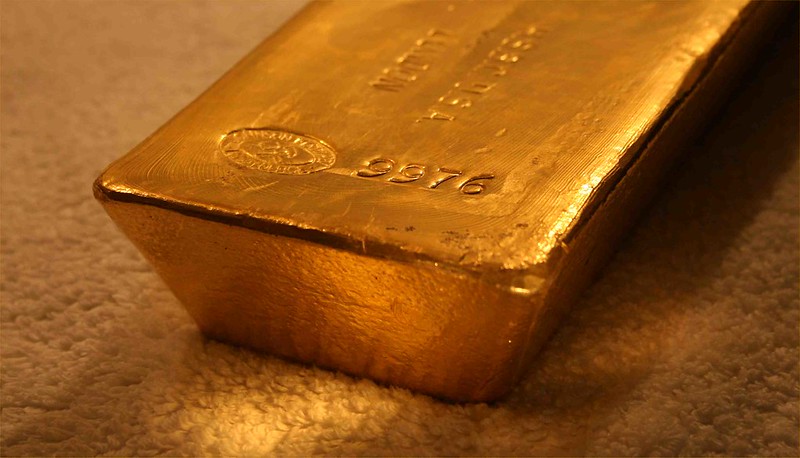

Lithium production in Argentina.

Electric vehicle battery material lithium should not be classified as a hazardous substance by the European Union because the scientific evidence on which the proposal is based is weak, seven industry groups said.

Lithium was added to the EU’s list of critical raw materials in 2020 because it is important for electric vehicles which are key to meeting targets for cutting carbon emissions.

The proposal by the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA), which cited studies based on lithium containing medicines used over the long term as a treatment for mood disorders, wants to classify lithium salts as dangerous for human health.

“The analysis finds only a “quite weak association” between lithium exposure and developmental effects, said Violaine Verougstraete, chemicals management director at Eurometaux, which represents the metal industry.

“For fertility, the opinion is based on selected studies with serious limitations, contradicted by more robust guideline studies which showed no effect of lithium exposure.”

EU member states are currently giving their views on the proposal to a committee which meets on July 5-6 to discuss chemicals including lithium that have been recommended for classification as dangerous.

A final decision is expected at the end of 2022 or beginning of 2023.

Classifying lithium as dangerous would have a major impact on Europe’s energy transition goals, the industry groups including Eurometaux and Recharge, the European industry association for rechargeable lithium batteries, said in a letter to the EU.

“Europe is at a critical period in its energy transition, needing to stimulate new investment into a full electric vehicle battery value chain,” the groups said.

“Europe is playing catch-up with China, which is already over a decade ahead, now controlling most global processing for lithium and other battery metals … Europe has a narrowing window of opportunity to attract the investments needed, and lithium is a central material to our success.”

Classifying lithium as hazardous will hamper investment in European refining and recycling capacity and give an advantage to companies in the electric vehicle battery supply chain outside the European Union, the letter said.

The proposal doesn’t ban lithium imports, but if legislated it will add to costs for processing companies from more stringent rules controlling processing, packaging and storage.

(By Pratima Desai; Editing by David Evans)

Image from Albemarle

Lithium and battery producers warned the European Union that a proposal to classify the metal as a reproductive toxin could severely hurt Europe’s burgeoning electric-vehicle industry.

The material is a key part of EV batteries and widely used in pharmaceuticals, industrial lubricants and specialty glasses. A proposal being considered by the European Commission this month would put some lithium chemicals in the highest category of reproductive and developmental toxins, based partly on human studies carried out in the 1980s and 1990s.

That may stigmatize use of the materials and cut investment in the EV sector, lobby groups including Eurobat, the International Lithium Association and Eurometaux said in an open letter to politicians. EVs play a crucial role in green efforts and automakers such as Elon Musk’s Tesla Inc. have warned that soaring materials prices and supply-chain bottlenecks threaten their rollout.

In the letter, the lobby groups raised concerns about the scientific rationale for the classification, which could lead to the chemicals being established as a “substance of very high concern” alongside severely carcinogenic and mutagenic toxins that the EU wants to gradually phase out by restricting usage.

That could undermine separate efforts to boost domestic production of lithium, which the commission designated as a critical raw material in 2020. The proposals refer to lithium carbonate, hydroxide and chloride.

“If the three lithium salts go down this path it could have significant unintended consequences in the EU, putting in question the long-term viability of lithium being produced, refined, used, and recycled” in the EU, International Lithium Association Secretary General Roland Chavasse said by email.

Categorizing the chemicals as reproductive and developmental toxins could impose higher costs on buyers and crimp producers’ margins, hindering the rationale for further investment in the industry, according to Francesco Gattiglio, director of external affairs for the EU at Albemarle Corp. The company is the world’s top lithium miner and operates a lithium chemicals plant in Langelsheim, Germany.

“While the impact to our specialty customers is unclear at this point, we do not anticipate closure of our Langelsheim plant,” Gattiglio said by email. “For sure, the classification would have a negative impact on the possibility to establish lithium conversion plants in Europe.”

(By Mark Burton)

California Governor Gavin Newsom. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

California on Thursday approved a plan to tax the electric vehicle battery metal lithium to generate revenue for environmental remediation projects despite industry concerns that it will harm the sector and delay shipments to automakers.

Governor Gavin Newsom, a Democrat, approved the tax as part of a must-pass state budget on Thursday. The state legislature had signed off on the levy during deliberations on Wednesday night.

The tax is structured as a flat-rate per tonne and will go into effect in January. The tax will be reviewed every year, and state officials have agreed to study potentially switching to a percentage-based tax.

The largest American state sits atop giant lithium reserves in its Salton Sea region, east of Los Angles, an area heavily damaged in the 20th century by years of heavy pesticide use from farming. Funds generated from the tax are earmarked in part to cleanup of the area.

Federal officials have praised the area’s start-up lithium industry because it would deploy a geothermal brine process that is more environmentally friendly than open-pit mines and brine evaporation ponds, the two most common existing methods to produce lithium.

Two of the area’s three lithium companies warned the tax would scare off investors and customers. Both said they may leave the state for lithium-rich brine deposits in Utah or Arkansas.

Privately-held Controlled Thermal Resources Ltd said the tax would force it to miss deadlines to deliver lithium to General Motors Co by 2024 and Stellantis NV by 2025.

EnergySource Minerals LLC, also privately held, said it halted discussions with potential financiers and an automaker.

“Supporting a tax that ensures lithium imports from China are less expensive for auto manufacturers to secure will devastate this promising Californian industry before it has begun,” said Rod Colwell, Controlled Thermal’s chief executive.

(By Ernest Scheyder; Editing by Michael Perry)