Perspective by SAP News

What’s News

U.S. President Joe Biden on Friday signed an executive order creating an emergency board to help settle disputes between major freight rail carriers and their unions. But thwarting a strike will not resolve an industry crisis: a severe labor shortage.

SAP’s Take

North America’s major freight railroads — BNSF, Canadian National Railway, Canadian Pacific Railway, CSX Transportation, Kansas City Southern Railway, Norfolk Southern Railway and Union Pacific Railroad — are suffering labor shortages equal to those of the air travel industry.

Bulk commodities, such as energy, agriculture, automobiles, and components, account for more than half of the freight moved by trains. Rail carriers transport 27.9% of U.S. freight, second to the 39.6% delivered by road, according to the U.S. Department of Transportation.

While retiring engineers and track workers account for a major part of the labor attrition, past layoffs and demanding schedules are also part of a very complicated problem.

“In the railroad industry, folks were let go,” said Timothy Motter, SAP solutions manager for the travel and transportation industries. “Now that those folks have been let go, they don’t necessarily want to come back. Railroad work is very difficult.”

Loop Capital, an investment bank that follows the railway industry, estimates that the industry is short about 4,100 workers, or about 9.4% of the needed workforce.

“Retention and hiring are not easy in the logistics industry in general, especially if you’re telling someone that they can’t go home, and that their schedule is up in the air every day,” Motter said.

Port delays have made scheduling for intermodal shipping — whereby shipping containers are loaded from one form of transportation to another — even more of a nightmare.

“Delays in getting containers through the port system and onto a train are really wrecking schedules,” Motter said. “If I can’t get a container on my train, I can’t fill up the train, but I still have to move the train on a scheduled basis.”

Like airlines, the railroad industry depends on tight schedules to keep operations staffed and profitable. But global supply chain and logistics problems have thrown that into havoc, making recruiting more difficult.

“It’s really difficult to bring someone back into the industry,” Motter said. “There’s a considerable amount of training that needs to occur to make sure workers are ready to handle themselves. To bring on a new employee is really difficult too. What happens to the new employee in a unionized industry? Well, they get the worst choices for work schedules, typically late or even in the middle of the night.”

The railroad industry’s chief competitor is trucking. To make railroads more competitive, the industry implemented a new way of shipping called Precision Scheduling Railroading (PSR) several years ago. Instead of allowing trains to sit still until fully loaded, PSR now focuses on loading individual cars. This enables the railroads to operate more meanly. But it also led to layoffs.

According to Motter, the shippers and unions say that “PSR cut headcounts too deep.”

Labor shortage for railroads that have slashed workforce by 33%

More wailing about workers

“No way did I realize how difficult it was going to be to try and get people to come to work these days…” CEO of CSX.

There are few hiccups in the US economy right now. James Foote, the chief executive of CSX, one of the largest railroads in the US, put it this way:

“In January when I got on this [earnings] call, I said we were hiring because we anticipated growth. I fully expected that by now we would have about 500 new T&E [train and engine] employees on the property,” he said. “No way did I or anybody else in the last six months realize how difficult it was going to be to try and get people to come to work these days.”

“It’s an enormous challenge for us to go out and find people that want to be conductors on the railroad, just like it’s hard to find people that want to be baristas or anything else, it’s very, very difficult,” he said. So even though we brought on 200 new employees, we fell short of where we thought we would be by now….”

Railroads are grappling with a weird phenomenon that is a combination of “labor shortages” and 12.6 million people still claiming some form of unemployment compensation, amid stimulus-fueled demand.

This comes after railroads had spent six years shedding employees in order to tickle Wall Street analysts and pump up stock prices. The North American Class 1 freight railroads combined—BNSF, Union Pacific, Norfolk Southern, CSX, Canadian National, Kansas City Southern, and Canadian Pacific—have tried to streamline their operations, using fewer but longer trains and making other changes, including the strategy of “precision scheduled railroading,” implemented first by Canadian National, then by CSX.

The resulting deterioration in service triggered numerous complaints from shippers. But one of the big benefits was that the workforce could be slashed, which fattened the profit margins at the railroads. Wall Street analysts loved it, and it was good for railroad stocks. By now, precision scheduled railroading has become the new religion at all Class 1 railroads except at BNSF, which has not officially adopted it, at least not completely.

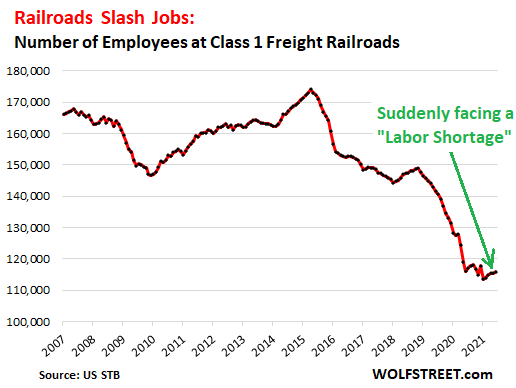

In the process, over the past six years, the Class 1 railroads have axed 33% of their workers through layoffs and attrition. According to the Surface of Transportation Board (STB), an independent federal agency that oversees freight railroads, the Class 1 railroads slashed their headcount from 174,000 workers in April 2015 to 116,000 workers in June 2021.

Before the railroads blame the 33% cut in the workforce on the pandemic, let’s point out that by February 2020, just before the pandemic, their headcount had already been cut by 46,000 workers, or by 26%, to 128,000. Only 12,000 workers were cut during the pandemic.

During the pandemic, some of the workers were put on furlough, to be recalled more easily. But it turns out that not all of them are eager to return to work on the conditions offered by the railroads, including relocation to new assignments.

These cuts in the workforce, and now the scrambling to hire people amid “labor shortages,” is contributing to issues in meeting heavy transportation demand: Union Pacific temporarily suspended traffic from Los Angeles into Chicago, and BNSF has started to meter traffic into Chicago, to allow them to catch up unloading the trains that are stuck in their Chicago rail yards. The resulting pot-banging by frustrated shippers has gotten the attention of the STB.

“The railroads cannot strip down to bare-bones operations,” STB chairman Martin Oberman told the Wall Street Journal. “It’d be like a professional football team only having one quarterback.”

The American Chemistry Council—which represents companies in the chemical industry, such as BASF, Chemours (the DuPont spinoff), Chevron Phillips Chemical, DuPont, ExxonMobil Chemical, etc.—lamented in a letter to the STB, cited by the WSJ, that railcars were waiting at railyards for over a week and travel times for some routes more than doubled. Some factories were running out of materials because shipments had gotten hung up and were approaching the point where they’d have to close, and other factories have cut production.

The railroads “clearly weren’t as prepared as they should have been for the increase in traffic,” Jeff Sloan, senior director of regulatory and technical affairs at the Council, told the WSJ. The deteriorating service shows that the railroads cut too deep before the pandemic and were unable to catch up, he said.

This is an excerpt from an article in Railroad Workers United News. It was written and published by Wolf Richter at WOLF STREET. Richter reports on “and dissects economic, business, and financial data, Wall Street shenanigans, complex entanglements, debacles, and opportunities.” His site is worth a visit.

Hear that lonely whistleThroughout Olympia’s history, railroads have crisscrossed the city’s landscape. As James Hannum notes in “Olympia’s Railroad History,” (an essay in the People’s History of Olympia) at various points in our city’s history, we hosted three “common carrier” lines, two logging railroads and a trolley line. While the last remaining segment of one historic line is still owned by the Burlington Northern Sante Fe (the modern successor of the old Northern Pacific), any trains you see operating on it are owned by Tacoma Rail, which is operated as a public utility by the City of Tacoma. The second railroad still in operation in Olympia is the Union Pacific. This rail line comes into an urban portion of our community up the Deschutes River valley, passing through the old Brewery Complex, under Capitol Boulevard via a tunnel and then into downtown Olympia, terminating at the Port of Olympia. Excerpted from Emmett O’Connell’s article History of the RR Lines that Cross Through Olympia, in Thurston Talk, 2014 |

After Slashing 33% of Workers in 6 Years, Railroads Complain about Labor Shortages, amid Uproar over Slow Shipments

“No way did I realize how difficult it was going to be to try and get people to come to work these days”: CEO of CSX.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

So there are few hiccups in the US economy right now. James Foote, the chief executive of CSX, one of the largest railroads in the US, put it this way during the earnings call yesterday (transcript by Seeking Alpha):

“I’ve never seen any kind of a thing like this in the transportation environment in my entire career where everything seems to be going sideways at the same time,” he said.

“In January when I got on this [earnings] call, I said we were hiring because we anticipated growth. I fully expected that by now we would have about 500 new T&E [train and engine] employees on the property,” he said. “No way did I or anybody else in the last six months realize how difficult it was going to be to try and get people to come to work these days.”

“It’s an enormous challenge for us to go out and find people that want to be conductors on the railroad, just like it’s hard to find people that want to be baristas or anything else, it’s very, very difficult,” he said.

“Nor did we anticipate that a lot of the people were going to decide they didn’t want to work anymore. So attrition was much higher in the first half of the year than what we had expected,” he said.

“So even though we brought on 200 new employees, we fell short of where we thought we would be by now….”

Railroads are grappling with a weird phenomenon that is a combination of “labor shortages” and 12.6 million people still claiming some form of unemployment compensation, amid stimulus-fueled demand.

And this comes after railroads had spent six years shedding employees in order to tickle Wall Street analysts and pump up stock prices. The North American Class 1 freight railroads combined – BNSF, Union Pacific, Norfolk Southern, CSX, Canadian National, Kansas City Southern, and Canadian Pacific – have tried to streamline their operations, using fewer but longer trains and making other changes, including under the strategy of “precision scheduled railroading,” implemented first by Canadian National, then by CSX.

The resulting deterioration in service triggered numerous complaints from shippers. But one of the big benefits was that the workforce could be slashed, which fattened the profit margins at the railroads. Wall Street analysts loved it, and it was good for railroad stocks. By now, precision scheduled railroading has become the new religion at all Class 1 railroads except at BNSF, which has not officially adopted it, at least not completely.

In the process, over the past six years, the Class 1 railroads have axed 33% of their workers through layoffs and attrition. According to the Surface of Transportation Board (STB), an independent federal agency that oversees freight railroads, the Class 1 railroads slashed their headcount from 174,000 workers in April 2015 to 116,000 workers in June 2021.

The results of the efforts to hire people back this year are barely visible in the chart – that risible uptick in employment over the past few months. Turns out, it’s a lot easier to cut workers than it is to suddenly hire workers:

Before the railroads blame the 33% cut in the workforce on the pandemic, let’s point out that by February 2020, just before the pandemic, their headcount had already been cut by 46,000 workers, or by 26%, to 128,000. Only 12,000 workers were cut during the pandemic.

Since September 2016 – the beginning of the STB monthly data by individual railroad – the biggest workforce slashers were CSX and Norfolk Southern, which both cut over 30%, and Union Pacific which cut nearly 30%. The other railroads cut far less over that period. But massive cuts occurred in 2015 and 2016, before this by-railroad data began.

During the pandemic, some of the workers were put on furlough, to be recalled more easily. But turns out, not all of them are eager to return to work on the conditions offered by the railroads, including relocation to new assignments.

These cuts in the workforce, and now the scrambling to hire people amid “labor shortages,” is contributing to issues in meeting heavy transportation demand: Union Pacific temporarily suspended traffic from Los Angeles into Chicago, and BNSF has started to meter traffic into Chicago, to allow them to catch up unloading the trains that are stuck in their Chicago railyards. The resulting pot-banging by frustrated shippers has gotten the attention of the STB.

“The railroads cannot strip down to bare-bones operations,” STB chairman Martin Oberman told the Wall Street Journal. “It’d be like a professional football team only having one quarterback.”

The American Chemistry Council – which represents companies in the chemical industry, such as BASF, Chemours (the DuPont spinoff), Chevron Phillips Chemical, DuPont, ExxonMobil Chemical, etc. – lamented in a letter to the STB, cited by the WSJ, that railcars were waiting at railyards for over a week and travel times for some routes more than doubled. Some factories were running out of materials because shipments had gotten hung up and were approaching the point where they’d have to close, and other factories have cut production.

The railroads “clearly weren’t as prepared as they should have been for the increase in traffic,” Jeff Sloan, senior director of regulatory and technical affairs at the Council, told the WSJ. The deteriorating service shows that the railroads cut too deep before the pandemic and were unable to catch up, he said.

In line with the executive order from the White House that exhorts agencies to work on making markets more competitive, the STB is now examining what can be done to improve competition among the railroads. Nixing any thought of mergers among Class 1 railroads would be a no-brainer.

SHORTAGE OF RAILROAD WORKERS THREATENS RECOVERY

Date: Friday, July 23, 2021

Source: Wall Street Journal

America’s freight railroads are struggling to bring back workers, contributing to a slowdown in the movement of chemicals, fertilizer and other products that threatens to disrupt factory operations and hinder a rebound from the pandemic, according to shippers and trade groups.

The problems have attracted scrutiny from federal regulators, who have been concerned that cost cuts and new operational plans implemented across most freight railroads that have been celebrated on Wall Street have resulted in lackluster service for some customers.

“The railroads cannot strip down to bare-bones operations,” said Martin Oberman, chairman of the Surface Transportation Board. “It’d be like a professional football team only having one quarterback.”

The board, which oversees freight railroads, is examining ways that it could improve competition in the rail industry, a mission highlighted in the Biden administration’s recent executive order to promote more competitive markets across numerous industries.

The challenges largely stem from two issues buffeting the U.S. economy: labor shortages and widespread supply-chain bottlenecks as manufacturing ramps up and the economy snaps back.

Railroad executives say they have done their best to manage through a pandemic that has forced swaths of their workforce to quarantine and caused fluctuating demand from irregular production at some plants.

CSX Corp. CSX +0.38% Chief Executive Officer Jim Foote said that the railroad had expected to hire 500 new conductors by now to help with the increased demand and higher-than-expected attrition, but has added only 200 so far. “It is an enormous challenge for us to go out and find people that want to be conductors on the railroad, just like it’s hard to find people that want to be baristas or anything else,” he said.

Railroads retrenched quickly when the economy seized up last year, furloughing thousands of workers and taking hundreds of locomotives offline. It came in the midst of a multiyear push by railroads like CSX, Norfolk Southern Corp. and Union Pacific Corp. UNP +0.54% to streamline their operations by running fewer trains with more cars, changes that already had resulted in fewer workers.

Some railroads implemented the Covid-related cuts in ways that would allow workers and locomotives to quickly be recalled should the pandemic ease quickly. Instead of furloughs, some railroads set up reserve boards that allowed the workers to use unpaid time off or work one week a month. That let them keep their benefits and return to duty in just 48 hours, instead of 15 days under normal furloughs. Idled locomotives were parked and maintained so that they could resume hauling trains.

But other workers who were furloughed have been slow to come back, with many of them balking at relocating to new assignments. Training took months and Covid-19 protocols stretched some training classes out further.

Shippers noticed. The American Chemistry Council, whose members include companies like Dow Inc. and Honeywell International Inc., said in a letter to the STB that railcars were waiting at yards for more than a week and travel times for some routes more than doubled. Some factories were close to closing because of lack of materials and others slowed production, the companies said.

Jeff Sloan, the trade group’s senior director of regulatory and technical affairs, said that the deteriorating service shows that the railroads cut too deep ahead of the pandemic and were unable to catch up. “They clearly weren’t as prepared as they should have been for the increase in traffic,” he said.

CSX, based in Jacksonville, Fla., was the first U.S. railroad operator to implement the operating philosophy called precision scheduled railroading starting in 2017, when Hunter Harrison, who pioneered the ideas on Canada’s major freight lines, joined the company as CEO. The strategy calls for running fewer trains longer distances and keeping them on a tighter schedule, allowing the railroad to scrap locomotives, employ fewer workers and shut facilities.

The implementation is jarring to operations and customers complained about mayhem on the tracks as the changes took place. But other railroads followed suit, in part due to Wall Street pressure to lower costs and boost margins and stock prices.

CSX and others say they have ramped up hiring lately to handle the increased shipping demand. Norfolk Southern had 114 conductors in training as of mid-June and plans to add between 72 and 96 new trainees each month for the remainder of the year.

CSX’s Mr. Foote said the challenges are prompting the railroad to re-evaluate its approach to hiring for certain jobs, such as those that require people to work during weekends and holidays, or spend days away from home. They are providing $3,000 bonuses to workers who provide referrals for new hires, which Mr. Foote said has helped boost the pool of applicants.

“It is a challenge for us to figure out ways to bring more normalcy to the hours worked by a railroad employee in order to make the job more attractive,” Mr. Foote said. “It’s not about the job.”

Across the freight rail network, employment levels still remain below pre-pandemic levels. According to data shared with the STB, railroads reported 47,444 transportation employees in June, down from about 51,800 in March 2020.

Not all railroads are scrambling to find workers. Union Pacific executives on Friday said the railroad has been able to hire workers to run their trains. CEO Lance Fritz said that furloughed employees, including some out of work for up to a year-and-a-half, are returning at a 70% rate.

“To date, while sometimes it’s difficult, we are finding the talent we need,” Mr. Fritz said.

The worker shortages are being exacerbated by congestion from products entering and exiting the rail system. Backlogs at ports mean strains on the freight railroads that are pulling cargo inland, while a tight market for trucking also creates pinch points when trains transfer containers to the highways.

“The supply chain is only as good as the weakest link in the chain and there are a lot of weak links in the chain,” Citi transportation analyst Christian Wetherbee said.

Union Pacific and BNSF Railway Co., a unit of Berkshire Hathaway Inc., BRK.B +0.33% have taken steps to mitigate some of the congestion of freight moving into Chicago. Union Pacific this week suspended traffic for seven days from certain West Coast ports into a Chicago intermodal facility to clear some of the backlog of trains waiting to be unloaded. BNSF said that it would be metering traffic from some West Coast ports into Chicago.

Mr. Oberman, the STB chairman, said that there are some industries that are reporting good service, but others continue to be plagued by the same issues, including crew shortages, late deliveries and other service cutbacks. “I don’t think we are overall having a system that works the way it should work,” he said.

Rail Industry Faces Worker Shortage

Welcome to Thomas Insights — every day, we publish the latest news and analysis to keep our readers up to date on what’s happening in industry.

Fayola Powell

Sep 05, 2018

Worker shortages have taken their toll on quite a number of industries in recent years, and the rail sector is no exception. The industry will need to hire more than 80,000 workers within the next six years in order to meet the increasing demand for transportation — for both people and commodities. Multiple factors must be considered when tackling the issue. Right now, the industry is trying its best to lure prospective candidates with financial incentives, such as signing bonuses worth thousands of dollars and more comprehensive benefits packages.

America’s focus on traditional schooling and career training is partly to blame, but the rail industry also has a reputation for involving exceedingly difficult, grueling work. Salaries simply don’t go as far as they used to in many regions; the industry’s rules and regulations are viewed as rigid and overly complex; workers are sometimes subjected to intense scrutiny, even in the form of supervisory drones; the hectic work schedules don’t leave much room for downtime; accidents are common; employees are given basic or inadequate benefits packages; and signing bonuses often involve a lot of fine print.

Overall conditions make for a challenging work environment, putting off prospective employees and painting an unappealing picture for the younger generation entering the workforce. The boomers are keeping things afloat right now, but many are retiring or reaching retirement age.

The rail industry must work to revamp its image. Heavy-handed, bureaucratic company policies have taken the shine off rail industry jobs, and while signing bonuses are certainly a solid starting point, the internal culture needs a complete overhaul. Improving the morale of current employees is a good place to start, helping to improve current conditions while also helping to attract the new generation of rail workers.

Resources:

- Overwhelmed by freight loads, railroads offer hefty hiring incentives to fill jobs

- Union Pacific, BNSF paying bigger hiring bonuses amid labor shortage

- NJ Transit, facing shortage, is slow to train locomotive engineers

- Trainorders.com

- Association of American Railroads

- What The Rail Industry Can Do To Prevent Sleeping Workers

- Union Pacific faces shortage of equipment and workers

- For big railroads, a carload of whistleblower complaints

- On American railroads, switch mistakes and speed cause an accident every other day

- Union Pacific spies with drones on their railroad workers

to see if they follow safety guidelines - Moving and storage: Careers in transportation and warehousing

- Occupational Employment Statistics

Image Credit: SimplyDay/Shutterstock.com