UK

Why doctors are angry about their 4.5 per cent “pay rise”

According to Health Secretary Humza Yousaf, the pay “uplift” of 4.5 per cent, backdated to April “demonstrates that we value all our medical and dental staff”.

To BMA Scotland, the award demonstrated exactly the opposite and was condemned as “hugely disappointing”.

The 4.5% rate meets the recommendations of the Doctors and Dentists Pay Review Body, which advises the UK and devolved governments, and is more generous than it might have been.

The Department of Health had proposed a two per cent uplift for doctors and dentists in England, while the Scottish Government’s sums would have equated to a basic salary increase of £700 for a junior doctor or £500 for a consultant.

READ MORE: Can we really say the NHS is in ‘recovery’ from Covid when activity has barely changed?

Instead, the basic pay for a first-year junior doctor on NHS Scotland will increase by £1,191 to £27,653, while the starting salary for a consultant will increase by £3,939 to £91,473. Overall, it adds £77 million to the annual NHS pay bill in Scotland.

The UK Government had warned that unaffordable pay awards would “lead to a reduced ability to expand clinical capacity and tackle the elective care backlog”, but the DDPRB cautioned: “pay awards that are too low have the potential to have significant budgetary downsides, including increased use of temporary staffing, understaffing and worse motivation, which can affect the quality of patient care and efficiency of services and undermine any budgetary benefit that lower pay awards might bring”.

Tuesday’s pay award is far from the end of the story, however; if anything it fired the starting gun on an increasingly bitter battle between health trade unions and ministers across the UK.

For medics, the bottom line is that a “pay rise” of 4.5% will be wiped out by inflation running at 9.1 to 11.1% (depending which measure you use); in this sense then, it represents a substantial pay cut.

What’s more, it comes on the back of a decade of successive real-terms pay cuts. A previous analysis by think tank, Nuffield Health, found that – based on consumer price index (CPI) inflation – average earnings for doctors in the UK actually fell by 9.1% between 2010 and 2019.

Source: Nuffield Health

Source: Nuffield Health

Having endured the pandemic, they emerge only to face record-breaking elective care backlogs, staff shortages, and a year-round winter crisis in A&E, with their incomes eroded further by rampant inflation at a time when senior clinicians also continue to be hit with punitive pension tax bills.

To paraphrase anchorman Howard Beale, doctors are “mad as hell and they’re not going to take this anymore”.

In England, BMA members have voted for “full pay restoration” – equivalent to a 30% increase in pay for consultants over the next five years that would bring salaries back into line with 2008 levels, based on retail price index (RPI) inflation.

READ MORE: Call to bring back free Covid tests amid warning NHS ‘ceasing to function’

The BMA, including BMA Scotland, had urged the DDPRB to recommend uplifts of RPI plus 2% in the current year: a 13.1% increase that would have taken the salary of a first-year junior doctor in Scotland to just under £30,000 and the starting salary of a consultant to £99,000.

Speaking last week, Professor Philip Banfield, the newly appointed chair of the BMA, said industrial action by medics in England is “almost inevitable”, with strikes by junior doctors most likely in the Spring.

The experience of the pandemic has been blamed for contributing to ‘burnout’ among doctors, with problems exacerbated by current backlogs

The experience of the pandemic has been blamed for contributing to ‘burnout’ among doctors, with problems exacerbated by current backlogs

North of the border, BMA Scotland has begun consulting members on “how we should respond” to the pay award.

“It will be entirely up to the membership across the profession about what level of action they might consider taking in response,” Dr Lewis Morrison, chair of the BMA in Scotland, told the Herald.

“Regardless of the question on industrial action, what we know for sure is that burnt out staff are already taking their own individual decisions to leave the NHS in Scotland.

“This is the last thing we need right now, with rising waiting times, delays across the whole system and an NHS that is beyond breakpoint.”

It comes against a backdrop of a wider threat of industrial action by nurses, midwives and other healthcare workers, such as physiotherapists, over their 5% pay offer.

For its part, the DDPRB acknowledged the effects of inflation but noted that “employers across the economy are not matching current high levels of inflation with their pay awards”, adding: “We do not believe that doctors and dentists should necessarily be exceptionally shielded from these increases to the cost of living faced by the wider population this year.”

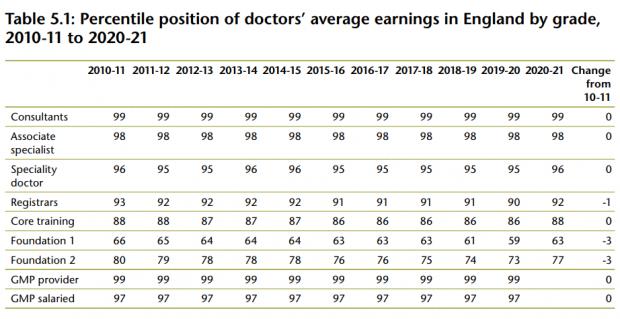

Its report shows that in 2010/11, the average total annual earnings of consultants put them within the 98-99th income percentile when compared against all full-time employees across the wider economy.

Source: DDPRB *NB: data relates to doctors’ pay for England, but salaries broadly similar in Scotland

Source: DDPRB *NB: data relates to doctors’ pay for England, but salaries broadly similar in Scotland

By 2020/21, this position was unchanged – they remained among the 98/99 percentile of top earners.

Of course, all that really tells us is that real-terms pay cuts have been hitting workers across the board.

Set against comparator professions, however, a first-year junior doctor earns more than a vet a the same grade, while consultants’ median earnings in 2021 exceeded the highest-paid vets and university academics, but lagged “substantially” behind equivalent senior professionals in finance, accounting or legal careers, for example.

And while down, half (49.8%) of the 47,000 medical and dental staff surveyed in 2021 reported being ‘satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ with their pay – ranging from 34.5% among trainees to 59.6% of consultants.

It is difficult to gauge, then, what the appetite for industrial action might be, or what form it might take.

READ MORE: Record numbers spend over 12 hours in A&E

Walkouts by doctors in Scotland are almost unheard of; in the UK as a whole, the only recent example was junior doctors striking in England in 2016 in protest over contracts.

Research by Imperial College London found that the action had a “significant impact on care”, including over 100,000 outpatient appointment cancellations and more than 25,000 fewer planned admissions than expected – though “no obvious change in the death rate”.

Bizarrely, there is some evidence that strikes by doctors can actually correlate with a reduction mortality.

An analysis of five walkouts lasting nine days to 17 weeks by doctors around the world, from 1976 to 2003, found no associated increase in deaths; population mortality either stayed the same, or fell.

The findings, published in the journal ‘Social Science and Medicine’ in 2008, seem counterintuitive until you delve deeper.

For example, in a Los Angeles strike over medical malpractice insurance premiums in 1976, only 50% of physicians took part, while Israeli medics striking over pay in 1983 set up their own temporary aid stations outside hospitals to provide emergency care for a fee.

In most cases, only elective treatment stopped and since all surgery comes with a mortality risk, it was these deaths which ceased when doctors withdrew their labour.

Total population mortality in Los Angeles fell from 21 deaths per 100,000 in week one of the doctors’ strike to 14 per 100,000 by week seven – lower than the five-year average.

This is cold comfort at a time when elective waiting lists have already ballooned, however.

Governments and NHS workers look set on a collision course with no easy answers.

Public sector pay rises - who decides and how?

Doctors, nurses and teachers are all threatening to strike as their pay goes up but they say that is not enough as it is below inflation, which has recently soared.

Alix Culbertson

Political reporter @alixculbertson

Tuesday 19 July 2022

Public sector workers including nurses, teachers and doctors have all had pay rises announced.

They have received increases of between 4.5% and 9.3% but unions say most of the pay rises are not enough as they are less than half the current level of RPI inflation.

As those in the public sector receive taxpayers' money, the amount they are paid is determined by their overall employer - the government.

However, there is a lengthy process to determine what their pay should be before ministers ever see a number.

How are public sector pay rises determined?

Pay review bodies

Independent pay review bodies play an integral role in informing the government's final decision on how about 45% of the public sector gets paid - including teachers, nurses, doctors, police officers and members of the armed forces.

They are made up of experts in their field and their appointments are made on merit, not political affiliation.

The process begins when the secretary of state for the relevant area requests recommendations on employee pay from the pay review bodies.

They will set a timeline and parameters such as asking the bodies to consider issues such as affordability, retention, recruitment and the state of the entire labour market.

Departments' spending on pay is limited by the amount of funding they receive from the Treasury.

Read more: Doctors demand 30% pay rise as some medics say they may have to go on strike

A range of sources, such as trade unions and their members, as well as employers then submit evidence to the pay review bodies, who will usually visit staff from their sector to determine concerns and opinions.

The government then also submits its formal pay offer at this stage for all levels of staff affected.

After receiving all the evidence from the relevant groups, the pay review bodies then recommend what the level of pay should be.

What happens after the recommendations are made?

The government chooses when it will respond to and publish the reports made by the pay review bodies.

Secretaries of state usually respond to the recommendations by issuing a written ministerial statement in parliament.

On the whole, the recommendations are accepted by secretaries of state, but there have been times when they have overridden the recommendations.

Sectors can disagree with the pay changes and can strike over the decision but the government has the ultimate say.

The latest pay rises will likely be implemented in the autumn but could be backdated to the start of April, when the financial year started.

Are there pay review bodies for all public sector jobs?

No.

Civil servants not in the senior civil service have their pay set by individual departments, according to guidance issued by the Cabinet Office and the Treasury.

Local government staff (not teachers) have their pay determined by their employers and trade unions.

Devolved governments - Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales - set their own pay policy for public bodies under their control.

TEACHERS and doctors have threatened fresh strike action after being offered a pay rise of at least 4.5 percent.

By MARTYN BROWN – DAILY EXPRESS SENIOR POLITICAL CORRESPONDENT

Tue, Jul 19, 2022

Police officers were also handed a £1,900 boost in what the Government says are the highest public sector pay rises in 20 years. But unions say the increases are a “kick in the teeth” as they are a real-terms pay cut due to high inflation, and warn of a wave of industrial action in the autumn.

Following a public sector pay review, more than a million nurses, paramedics, midwives, porters and cleaners will get a rise of at least £1,400, with the lowest earners receiving up to 9.3 percent backdated to April, the Department for Health said.

Dentists and doctors will get 4.5 percent while the average basic pay for nurses will go up from £35,600 to £37,000. Newly qualified nurses will get 5.5 percent taking their pay to £27,055. On Monday Health Secretary Steve Barclay said of the rise: “Very high inflation-driven settlements would have a worse impact on pay packets in the long run than proportionate and balanced increases now, and it is welcome the pay review bodies agree with this approach.”

But Danny Mortimer, chief executive of NHS Employers, said while they were pleased the pay rise for NHS staff was above the original three percent, it still places NHS and public health leaders in the “impossible position of having to choose which services they will cut back on in order to fund the additional rise”.

Meanwhile, the starting salaries for teachers outside London will rise by 8.9 percent to £28,000.

Teachers who have been in the profession for more than five years will get a five percent increase from September.

Education Secretary James Cleverly said: “We are delivering significant pay increases for all teachers despite the economic challenges, giving teachers the biggest pay rise in a generation.”

The £1,900 across-the-board pay hike for police officers amounts to an average five percent. Those on the lowest pay are getting a rise of up to 8.8 percent. The highest paid will receive between 0.6 percent and 1.8 percent and the minimum starting salary for a police constable degree apprentice will increase to £23,556.

Home Secretary Priti Patel said: “It is right that we recognise the extraordinary work of our officers who day in, day out, work tirelessly to keep our streets, communities and country safe.”

All the rises were recommended by independent public sector pay review bodies, who take evidence and talk to those in the industry.

Their recommendations were all accepted in full by the different government departments, who said the increases recognise the contribution of key workers while balancing the need to protect taxpayers, manage public spending and not drive up inflation.

But union bosses were furious at what they call “a massive national pay cut”.

Unite general secretary Sharon Graham said: “The Government promised rewards for the dedication of the public sector workforce during the pandemic.

“What they have delivered instead, in real terms, is a kick in the teeth.

“We expected the inevitable betrayal but the scale of it is an affront.”

Both the NASUWT and NEU teaching unions said the proposed increase of five percent for more experienced staff is too low. The NEU has said it will now consult its members

on whether to take strike action in the autumn.

Kevin Courtney, the joint general secretary, said the five percent increase would mean “yet another huge cut” to the real value of pay against inflation.

“It is a double whammy that lets down the teaching profession and the pupils in our schools,” he said.