How a black man's murder put racism in the spotlight ahead of Italy's snap election

By Andrea Carlo • Updated: 10/08/2022

Demonstrators gather during a protest to demand justice for Nigerian street vendor Alika Ogorchukwu in Civitanova Marche, Italy. Saturday, 6 August 2022 - Copyright Antonio Calanni / AP

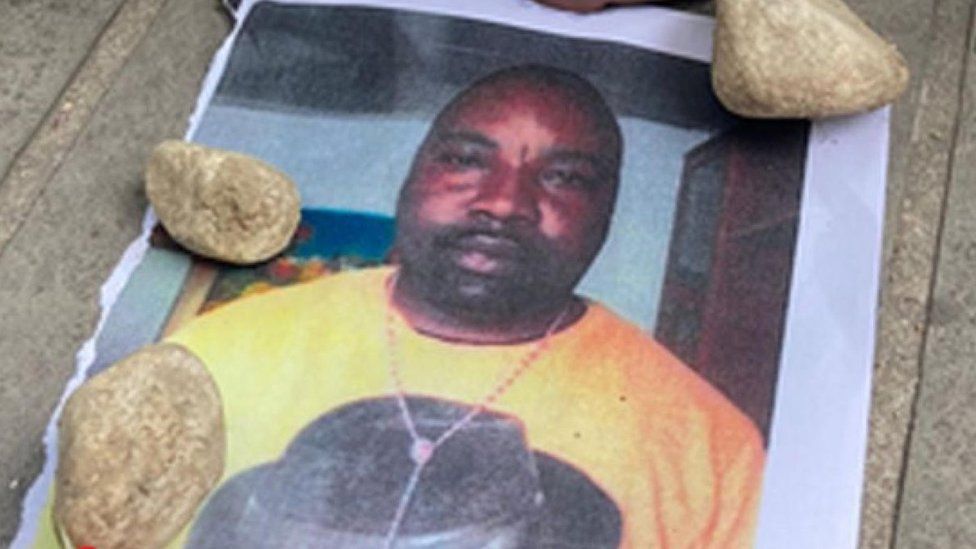

The murder of Alika Ogorchukwu, a Nigerian man living in Italy, has sent shockwaves across the country and sparked a set of debates on racism.

The 39-year-old was a street vendor in Civitanova Marche, a seaside resort in the central region of Marche. The alleged assailant, Filippo Ferlazzo, is reported to have beat Ogorchukwu to death after an altercation on 29 July, which was filmed by onlookers, none of whom directly intervened. Investigators have ruled out a racist motive, citing Ferlazzo's psychiatric problems; campaigners, on the other hand, have contended this decision and argue that prejudice was at play.

A mere ten days later, the same town was the setting of another horrific murder, as a 30-year-old Tunisian man was stabbed to death. While the cause of the crime is yet to be ascertained, it marks yet another horrific act of violence against an immigrant living in the country.

Ogorchukwu's murder is far from the country’s first major incident of violence against people of colour. Four years ago, a former local candidate for the anti-immigration Northern League party, Luca Traini, shot and injured six African immigrants in Macerata, also in Marche.

Anti-racist activists claim that heightened tensions and rhetoric against immigration are responsible for such acts of aggression. A set of demonstrations and vigils were organised across Italy earlier this month, with protestors calling for justice for Ogorchukwu.

It comes as polls indicate a "centre-right" coalition, headed by the far-right party Brothers of Italy, looks likely to triumph in snap elections next month. Giorgia Meloni's party has founded much of its electoral success on its anti-immigration stance, numerous Italians of colour and immigrant background wonder whether the coming months could lead to increased instances of racist hostility or even outright violence.

Where do Giorgia Meloni and Matteo Salvini stand on immigration?

The coalition comprises three major parties - Meloni's Brothers of Italy (Fratelli d’Italia), a nationalist force with neo-fascist origins; the Northern League (Lega Nord), a populist and formerly regionalist party headed by Matteo Salvini; and ex-prime minister Silvio Berlusconi’s liberal-conservative Go Italy (Forza Italia).

Following the collapse of incumbent prime minister Mario Draghi’s big-tent coalition government last month, the country was hurtled into an unexpected set of general elections slated for 25 September, where the centre-right coalition - collectively polling at above the required majority threshold of 40% - is currently set to win.

Meloni’s iron-fist approach has affirmed her plans to stop "mass immigration" and "Islamisation", which she vigorously restated at a recent far-right conference in Spain.

Giorgia Meloni: 'The left has been complicit for decades in the immigration emergency, endorsing and promoting irresponsible policies. The management itself by Minister Lamorgese was disastrous. It is time to reverse course and restore dignity to Italy by defending its borders.'

Her coalition colleague, Salvini, has also based his career heavily on anti-immigration rhetoric and is not doubling down in this electoral race. The leader of the populist Northern League and former deputy prime minister of a short-lived coalition government with the Five Star Movement from 2018 to 2019, he is the signatory of the deeply controversial ‘Security Decree’ (Decreto Sicurezza), which would make it illegal to provide humanitarian assistance to clandestine immigrants crossing the Mediterranean.

In 2018, Salvini also called for a “mass cleansing, street by street, piazza by piazza, neighbourhood by neighbourhood” of Italy, which certain critics claim incited the kind of tense, racialised atmosphere which led to Traini's aforementioned terrorist attack in 2018. The League politician himself blamed "uncontrolled immigration" for the shooting.

The third of the main coalition leaders -- Berlusconi -- has taken a somewhat less inflammatory approach to immigration but has also expressed similarly hard-line attitudes.

Back in 2010, the infamous former prime minister -- who has been definitively convicted of tax fraud and accused of sexual misconduct -- stated that illegal immigrants were not welcome in Italy, but "beautiful girls" were.

More recently, in the run-up to the 2018 general elections, Berlusconi pledged to deport 600,000 illegal immigrants from the country.

‘Racism is a deeply rooted issue in Italy’

Tragedies such as Ogorchukwu’s murder have often been portrayed as anomalous incidents that do not reflect wider societal problems in Italy. But for certain Italians of colour and immigrant background, it's the violent manifestation of an insidious structural issue.

Angelo Boccato is an Italian journalist of Afro-Dominican descent. An outspoken critic of Italy’s nationality laws -- which favour heritage over upbringing -- he posits the murder within a broader social malaise.

“Racism in Italy is a deeply rooted issue linked to its colonial and fascist history,” he told Euronews. “Colonial history has been denied

"The murder of Alika is not an extraordinary event at all," he remarked. "Just a few years ago a Nigerian man was murdered in the same region… [and] it’s not just a problem in the Marche."

Indeed, Italy itself has a colonial history as a result of its exploits in Northern and Eastern Africa under the fascist regime in the 1920s and 30s - one which many activists claim has not received adequate public attention. For instance, the legacy of the late journalist and author Indro Montanelli -- who had served in Italian Ethiopia and had expressed white supremacist views -- came under attack in 2020, in the midst of the Black Lives Matter demonstrations. The country's record of violent incidents against people of colour was also concomitantly exposed and scrutinised.

Regarding a possible Meloni-Salvini-Berlusconi coalition government, Boccato noted how the "strength of far-right and right-wing views is so wide[spread]... just in 2018, support for Brothers of Italy was only at 4-5%."

"The prospect of the victory of the right is really worrying," he added. "[But] the signals are already in the country. It's a country which is still unable to confront its past and to change its citizenship laws to make them modern and inclusive."

Boccato's thoughts are echoed by Oiza Obasuyi, a junior researcher at the Italian Coalition for Freedoms and Civil Rights (Coalizione Italiana per le Libertà e i Diritti civili), who cites the country's citizenship laws and the immigration policies unveiled during Berlusconi's tenure in 2002 -- which added hurdles for migrants wanting to settle in the country -- as an example of Italy's more structural problems with race.

"Italy constantly denies systemic racism," Obasuyi told Euronews. "We only talk about racism when confronted with blatant acts of aggression with racist undertones, but we never question the system in which we live."

Looking at Ogorchukwu's murder, Obasuyi claimed she was less interested in the killer's motive itself, but rather the conditions the victim found himself in.

"We need to think about the working conditions in which he found himself," she asserted. "Foreigners in Italy, as a result of [the country's immigration laws], are those who most often live on the margins of society, working in precarious and exploitative job sectors."

But for Obasuyi -- unlike Boccato -- a potential far-right government is not the main concern, since she sees structural racism as being an issue of all major parties in the country.

"Just talking about racism during the electoral season means seeing racism just in the far-right," she claimed. "Racism is not just an 'emergency'... it's the constant reality in this denialist country."

While many immigrants and Italians of colour fear the prospect of a Meloni-led government, there are others who have taken an entirely different attitude.

Meet 22-year-old Asha Fusi, a psychology student in a small town outside of Milan. Born in India, she was adopted by an Italian family at the age of four and has written a book about her experience moving to her new country.

In 2018, she also made national news for becoming a councillor in her town -- Ceriano Laghetto -- and, at just 18, the country’s youngest councillor.

Fusi, unlike many of her age and background, is enthusiastic about the possibility of a right-wing government, and, moreover, does not believe that Ogorchukwu’s murder reflects a wider racial malaise in Italy.

“I hope that the centre-right can rise to the government, I am positive and I believe that it can finally be the turning point towards change,” Fusi told Euronews.

“I think [Ogorchukwu’s] murderer has some kind of mental problems and probably has racist ideas too,” she told Euronews. “I don’t think it’s part of a wider structural problem.”

Indeed, Ogorchukwu’s widow herself, Charity Oriakhi, has not supported the notion that her husband's murder was racially motivated, stating she had never been a victim of racism prior to the incident.

The Northern League and Brothers of Italy may be renowned for their anti-immigration rhetoric, but Fusi is far from the only Italian of colour to lend her support to the right-wing coalition.

Nigerian-born Tony Iwobi is a senator for the Northern League and has shared Salvini’s strong line against clandestine immigration.

“The Lampedusa hotspot is the result of a failed migration policy that feeds social insecurity and precariousness," he tweeted in July, criticising the former government's approach to the processing of asylum claims on the Sicilian island of Lampedusa, off the Tunisian coast.

Despite fears that a Meloni-Salvini-led coalition could give rise to intensified xenophobic and racist sentiment, Fusi sees no cause for concern.

"I don't think that a Salvini/Meloni government could create that,” she remarked. “These kinds of ideas against immigrants are first born in people's own minds. So whatever the government will be, it could never change people's ideas and thoughts regarding this issue."

Additional sources • AP

Letter from Africa: How racism haunts black people in Italy

EPA

EPAIn our series of letters from African journalists, Ismail Einashe writes that many black people in Italy feel that racism is not taken seriously.

For Italian-Eritrean filmmaker and podcaster Ariam Tekle, there is no doubt that the recent killing of a disabled Nigerian street vendor, Alika Ogorchukwu, in Italy was a "racist murder".

This is despite the fact that local police have ruled out racism as a motive for the 39-year-old's killing in the seaside town of Civitanova Marche.

He was reportedly selling handkerchiefs when he was chased and beaten to death. None of those who witnessed the broad daylight attack appeared to intervene.

A suspect - a white man named as Filippo Claudio Giuseppe Ferlazzo - has been ordered to remain in jail as the investigation continues.

A police investigator said Mr Ogorchukwu was attacked after the trader's "insistent" requests to the suspect and his partner for spare change.

Nevertheless, his horrific murder - caught on video - has firmly put the spotlight on racism in Italy.

In 2016 another Nigerian man, Emmanuel Chidi Namdi, was killed after defending his wife from racist abuse in the town of Fermo in central Italy.

Two years later, a far-right extremist shot six African migrants in a drive-by attack in a town about 25km (15.5 miles) from where Mr Ogorchukwu was killed.

When the police arrested him, he was wrapped in the Italian flag shouting "Viva l'Italia", telling police he wanted to "kill them all".

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGESIn fact this region of Le Marche has been governed since 2020 by the far-right party Fratelli d'Italia (Brothers of Italy).

It is led by Giorgia Meloni, who could become Italy's first female prime minister if she wins a snap election to be held in September.

The party, which is expected to emerge as the single largest, is part of a wider conservative bloc that includes the right-wing Lega (League), led by Matteo Salvini and the conservative Forza Italia (Forward Italy), led by former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi.

Ms Tekle says black people in Italy regularly experience racist violence, police harassment and discrimination, and the rise of far-right anti-immigration parties has "normalised" racism.

But, she adds, most Italians grow up with the attitude that racism is not that serious in their country.

"They always say it's 'ignorance' or something else. They don't want to admit that there is racism in Italy. They always say America or the UK is worse."

In recent years Italy, a country long known for its history of mass emigration, has become one of Europe's migrant hotspots.

The country has struggled to cope with this historic reversal and to integrate migrants successfully into Italian society.

Ms Tekle was born and raised in a working class neighbourhood in the city of Milan. Her family has been in Italy for five-decades, yet she feels marginal in a society that, she says, refuses to see her as one of them.

"I speak with a Milanese accent but they ask me all the time where I am from."

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGESItaly also makes it more complicated for those born to migrant parents to obtain Italian citizenship - it is not an automatic right and they have to wait until they are 18 to apply, making them feel more like outsiders.

Alessia Reyna, a student and member of an anti-racist network, says that even though she is very Italian, she will never be recognised as such because she is a black woman.

Ms Reyna was born in Rome to an African-American father and Afro-Peruvian mother, who met outside the Colosseum of the eternal city and fell in love.

She grew up in a small town near Milan. She went to school there, but chose to continue her studies in the UK.

Ms Reyna says that Italy is not ready to look at issues of structural racism.

She points to another recent case when Beauty Davis, a young Nigerian who worked as a dishwasher in a restaurant in Calabria in the south of Italy, was allegedly slapped after she demanded her wages.

"She just asked to be paid, but she was attacked. I don't think a white woman would have been attacked," Ms Reyna says.

Ubah Cristina Ali Farah, the award-winning Italian-Somali novelist, expresses a similar view.

She says that very few Italians are aware about the colonial history of their country and how this might impact on the experiences of non-white Italians.

Italy was the colonial power in Eritrea, Somalia, Libya and also occupied Ethiopia in the 1930s under Benito Mussolini's fascist regime.

Ms Ali Farah's family has been in Italy for more than half a century, but she says: "If they don't recognise those of us with colonial ties to Italy as being Italian, how will they ever recognise those people who arrived on boats to Italy or their children as Italian".