Now more than ever: Let’s get the Equal Rights Amendment finalized

As women of faith, we are committed to the common task of making the ERA the law of the land.

(RNS) — Recent Supreme Court opinions dangerously undermine women’s equal protection under the law. As women of faith, we are alarmed and active. Each of us has struggled against patriarchal interpretations of texts and teachings that undermine women’s autonomy and rights. We reject the mainstreaming of repressive religious interpretations in shared public spaces that derail our quest for equal justice.

On Women’s Equality Day, we affirm the Equal Rights Amendment as an essential next step to protect women’s rights and dignity.

Justice and equality are at the heart of the human project. American history is replete with diverse, multifaith coalitions that advance cultural shifts toward inclusivity. It is appalling that the Supreme Court in Dobbs v. Jackson overturned abortion rights based on the literal text of a centuries-old document that excluded women from its inception. “The Constitution makes no reference to abortion, and no such right is implicitly protected …,” wrote Justice Samuel Alito.

We recognize this brand of originalism from religion. Opposing justice because a text does not mention a word or emerged from a patriarchal context is a familiar argument made to preserve hierarchical power. It has long been common conservative practice to declare that the sexist historical context in which a document was penned should remain the norm today — just as the court did.

Many of our religious texts make no explicit mention of the terms “abortion,” “homosexuality,” “same-sex marriage” or “the declaration of human rights,” but all emphatically insist on justice.

Islamic ethics allow for many views on abortion, depending on what kind of scriptural sources are considered and by whom. (SDI Productions/E+ via Getty Images)

In Islam, the word “abortion” does not exist; the supreme right and well-being of the mother do. For centuries, a Muslim woman has had the right to end her pregnancy whether for the mother’s health or for economic reasons. A fetus’s personhood is only recognized with the baby’s first gasp of air.

Judaism has a similar belief rooted in Exodus. The Jewish tradition has such reverence for human life that the pregnant person is held in high regard. Abortion is not only mandated to save the mother’s life but is permitted to save her from great distress, physical or emotional. The ancient rabbis described a fetus as part of the mother’s body, which does not take on personhood until the majority of the head emerges from the womb.

Protestant and Catholic Christians hold diverse views of abortion and women’s equality. A thread of misogyny runs through traditional orthodoxy; control of women remains a consistent theme in many theologies. Yet, Christian sacred texts highlight the dignity and empowerment of women in accord with Jesus’ teaching that all are equal.

Christian Scriptures are silent on abortion. There is no Christian consensus on when fetal life begins. Many feel compelled by their faith to respect women’s moral agency to make prayerful choices about childbearing and family life. Opposition to responsible reproduction is a minority view among U.S. Christians. It should not be accorded broad legal authority in a pluralistic society.

The Sikh tradition proclaims the equality and dignity of women. Sikh sacred texts present a vision of a world where people of all castes, creeds and genders are sovereign in their bodies. Any ban on abortion is a violation of this core belief. To strip away a woman’s freedom to care for her body — to decide when, whether and how to bring children into the world — is to deny her intelligence and humanity.

In 1802, Thomas Jefferson stated that “a wall of separation between Church and State” was a foundational element of American democracy. Since then, the U.S. Supreme Court has repeatedly cited Jefferson’s words as justification for the priority of secular law over the teachings of any individual faith. We live in a democratic society where rule of law, not fiat, should control.

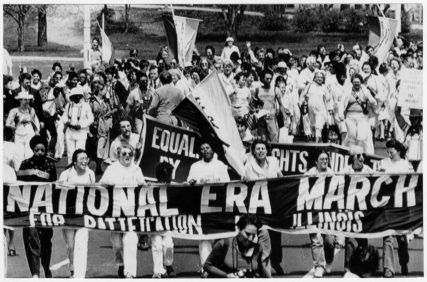

Part of a crowd of 25,000 demonstrators march along Chicago’s lakefront on May 10, 1980, in support of the Equal Rights Amendment. Many churches and religious organizations participated in the event. RNS archive photo. Photo courtesy of the Presbyterian Historical Society

The Equal Rights Amendment will play an important role in ensuring such a democracy. By inserting these words in the Constitution: “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged … on the basis of sex,” we can correct the intentional exclusion of women. For the first time in U.S. history, people of all genders will be citizens of equal stature.

This nation is a hair’s breadth away from finalizing the ERA. It has been duly ratified by 38 states and needs only to be published by the U.S. archivist. We call on President Biden to ensure that this happens swiftly. We call on the U.S. Senate to affirm that there is no arbitrary deadline on the ERA’s adoption.

Recent Supreme Court decisions, with repercussions in the states, have shown us how urgent this reform is. As women of faith, we are committed to the common task of making the ERA the law of the land. We invite all people of goodwill to join us as we get it done.

(Ani Zonneveld is the founder and president of Muslims for Progressive Values. Lisa Sharon Harper is the president and founder of Freedom Road. Mary E. Hunt, Ph.D., is cofounder and codirector of the Women’s Alliance for Theology, Ethics, and Ritual (WATER). Valarie Kaur leads the Revolutionary Love Project. Rabbi Sharon Brous is the senior and founding rabbi of IKAR and a leading voice in reanimating religious life in America. Allyson McKinney Timm is a human rights lawyer and the founder of Justice Revival. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)