Bloomberg News | August 28, 2022 |

Graphite from the Vittangi project. (Image by Talga Group).

Talga Group Ltd. has waited for more than a decade to go ahead with a graphite mine in Sweden that could supply enough battery material to power two million electric cars a year and reduce the continent’s dependence on China.

Yet after some signs of progress, the Australian company is back in administrative limbo on its Nunasvaara South site after a court date for an environmental permit was postponed until February. The slow process has left the project at the prospecting stage since 2011.

“The basic problem we’re getting is that there is this unlimited processing time,” said Martin Phillips, chief operating officer at Talga, which says graphite from its mine and refinery running on renewable energy will make the world’s greenest electric vehicle battery anode. “That creates the challenge for us to keep financing our company while we wait for the Swedish authorities to make a decision.”

Two years ago, the European Union highlighted Sweden’s vast mineral resources, which include about half of the 30 raw materials the bloc considers critical to meeting its goals for green technology such as EV batteries. Sourcing them from within the EU would ease reliance on China at a time when supply chain snags and geopolitical tensions are fueling a push toward greater self-sufficiency.

Yet prospects for getting projects underway look more uncertain than ever because of a lengthy permitting framework and fervent local opposition, miners say.

While Sweden has a centuries-long history of extracting metals from the earth and ranks as Europe’s biggest iron ore producer, new projects have been beset by concerns over the environment and encroachment on the indigenous Sami population in the north — whose reindeer grazing rights are crucial to its livelihood.

“Mines always entail a large impact on both the environment and other activities, such as reindeer herding and tourism,” says Jonas Rudberg, a spokesman for the Swedish Society for Nature Conservation, an environmental group.

Rare Earths

In Southern Sweden, a struggle over mining rare earth minerals in Norra Kärr — deemed the most promising deposit of its kind in Europe — has spanned more than a decade. Locals fear a mine would not only destroy the surrounding farms and forests but also contaminate nearby lake Vättern, the source of drinking water for 300,000 people.

Such accidents aren’t without precedent. In 2012, leaks from a tailings pond at the Talvivaara nickel mine in neighbouring Finland spilled toxic levels of metals and uranium into nearby lakes and rivers in one of the country’s worst environmental disasters.

Industry executives say local concerns risk standing in the way of broader technological shifts that would help the environment and fight climate change.

“It’s a double standard,” said Roberto Garcia Martinez, chief executive officer of Eurobattery Minerals AB, an exploration company looking to develop sustainable and ethical mineral mines in the EU. “Everyone wants to drive electric cars, but we don’t want to have a mine in our back yard — and that needs to change.”

The region’s plodding progress toward a mining base capable of powering the EV transition stands in contrast to the speed with which battery-cell maker Northvolt AB set up an independent supply chain. The Swedish company, which gets graphite from China, has encouraged the development of domestic mines while funding research into alternative battery technologies.

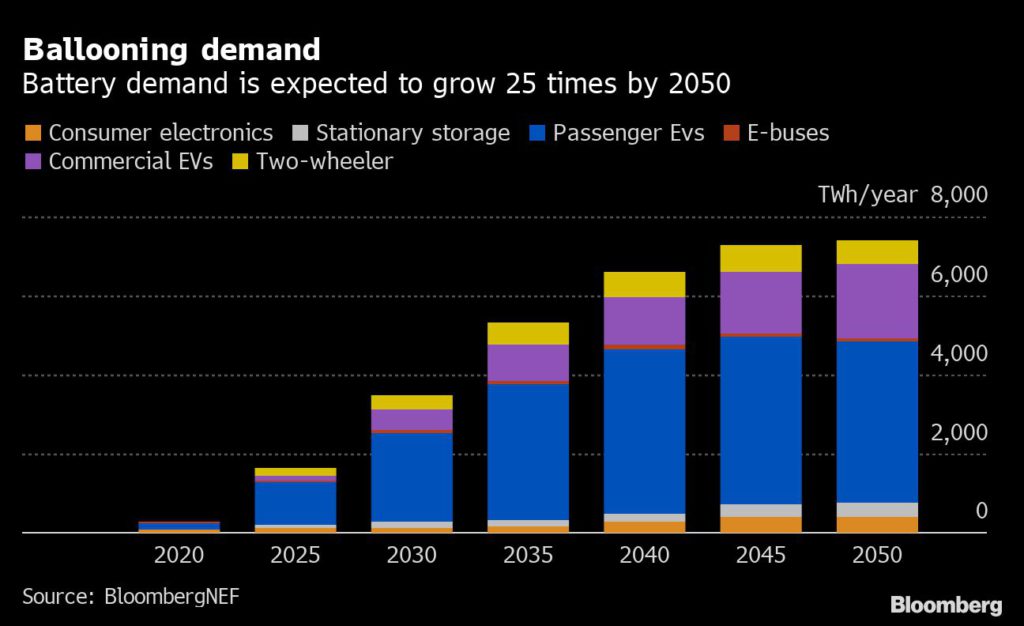

As EV sales take off, the European Commission estimates that demand for lithium, a crucial ingredient in batteries, will increase by as much as 18 times by the end of the decade. Cobalt use is set to climb by some five times.

Rudberg said he hopes some demand for these raw materials can be met through mines “where it won’t conflict too much with other interests.” He also stressed the importance of other avenues for making the green transition — such as battery recycling and lowering consumption.

“It is a bit unrealistic to imagine a future where all of the earth’s population drives a Tesla,” Rudberg said. “The earth’s resources won’t be enough.”

Sweden’s Economy Ministry is carrying out an inquiry into how to streamline the permitting process to ensure a sustainable supply of “innovation-critical” metals and minerals. The review sought input from industry, legal and environmental experts, including Rudberg, and the results are expected in October.

“The process scares a lot of people away who want to invest in Swedish mines, since it is so uncertain if you will get a permit or not, even if you are doing everything right,” said Maria Suner, CEO of the Swedish Association for Mines, Mineral and Metal Producers.

Erika Ingvald of The Geological Survey of Sweden, who acted as an expert on the inquiry, hopes it will lead to a simpler process. As for the mines awaiting a decision, she said she’s unsure when they can expect progress.

“It is like playing the lottery,” she said. “It’s almost impossible to say.”

(Reporting by Isabella Anderson).