Workers Undermined Canada’s Attempt to Crush the Bolshevik Revolution

The Bolsheviks held power in Russia for mere months before 13-Allied states, in unison with White Russian and Czecho-Slovak Legion fighters, launched a four-front war to squash the revolution. Among the more than 2,000,000 troops that would eventually enter combat was just over 4,000 Canadians who made up the Canadian Expeditionary Force (Siberia) (CEFS). This was Canada’s first foray into combat on their own terms, formally acting independently of the British. The government saw it as a chance to prove their newfound independence and share in the spoils of war. Instead, the expedition ended up as an abject failure, due in large part to the growing labour movement in Canada.

Canadian Prime Minister Robert Borden had several reasons to move against the Bolshevik government, which he refused to recognize. The Canadian bourgeois class had long eyed Russia’s far-east as a lucrative land due to its vast resources. The Provisional Government had made efforts to assure them that they’d be able to conduct their business, with the land open for investments. Yet the Bolsheviks were not willing to sell out their country, and began nationalizing industries, as well as gold. They also repudiated nearly 13 billion rubles in loans to the Allies.

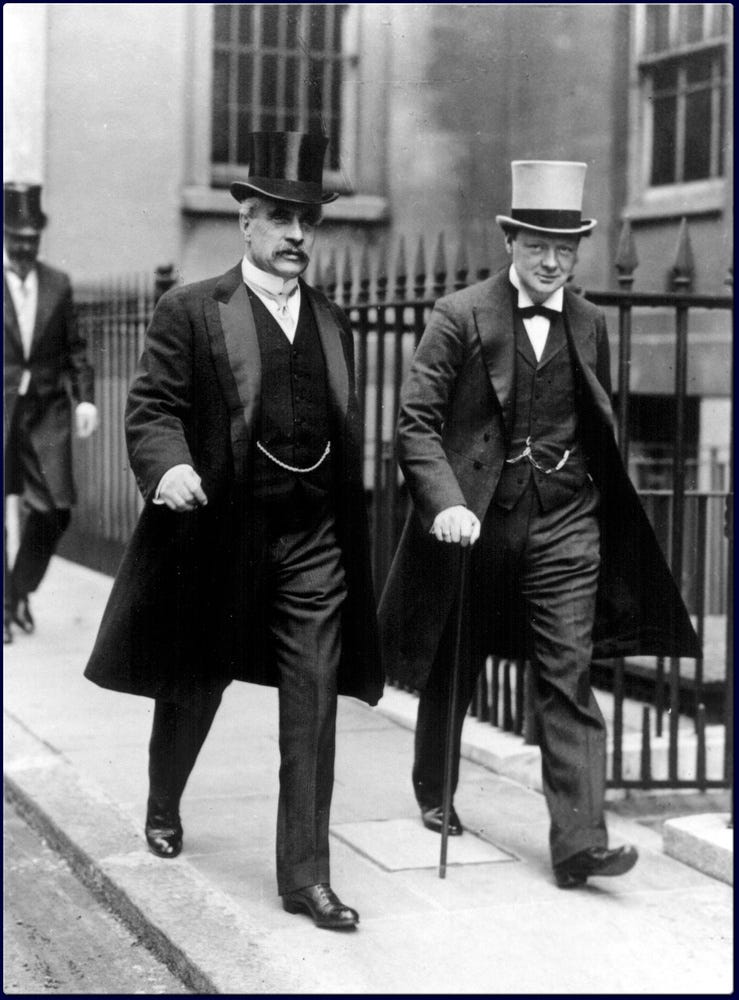

There were several military related reasons offered as well. Intervening against the Bolsheviks could bring Russia back into the war, therefore forcing Germany to resume a multipronged battle. Benjamin Isitt, the author of the seminal history of the CEFS, From Victoria to Vladivostok, wrote that, “The Canadian bourgeoisie, which became rich during the world war, tried to gain independence, especially in foreign policy. It believed that Canadian participation in the intervention would help to reach this goal.” Finally, the Bolsheviks were perceived as an ideological threat that could cause widespread damage, at home and abroad, if left unchecked.

On July 9, 1918, the British War Office sent a request to Borden asking if he could make troops available to “restore order and a stable government” in Siberia, join forces with the Czecho-Slovak Legion, and restart combat with Germany on the Eastern Front. Borden began discussing the venture with advisors, and on July 28, the Privy Council approved the expedition. By August 13, the details of the CEFS were made public: more than 4,000 troops — including 135 Russian members of the Czar’s former army and a one woman, a nurse — and 3,000,000 rounds of ammunition would be sent from Victoria, B.C. to Vladivostok, a port city in Russia’s far-east that would come to be the launching point for Western intervention. The Canadian army would also operate independently of the British.

As the government was pulling together the CEFS, socialism was exploding in popularity in Canada, with strikes breaking out and new unions emerging. The turmoil, which had spread throughout the country but was most potent in B.C. and other Western provinces, was largely due to conscription, introduced by Borden through the Military Service Act on August 29, 1917.

The government was aware of this unrest, and made moves to combat it, both for the sake of business at home and the ability of the CEFS to be successful abroad. According to Isitt, “The same attitudes that shaped Allied strategy in Russia — the use of force to quash Bolshevism — informed domestic responses to labor unrest.” This included: Privy Council Order 2384, brought into law on September 28, 1918, which made 14 working class and socialist organizations illegal under periods of war; the banning of several socialist publications; the censorship of popular socialist texts (those found to be in possession of Vladimir Lenin’s “Political Parties in Russia” essay could be punished with five-years imprisonment or a $5000 fine); the banishment of labor strikes, with a clause that allowed the government to force strikers into the army. Yet despite this feverish attempt to crack down on burgeoning radicals, they would end up undermining the CEFS.

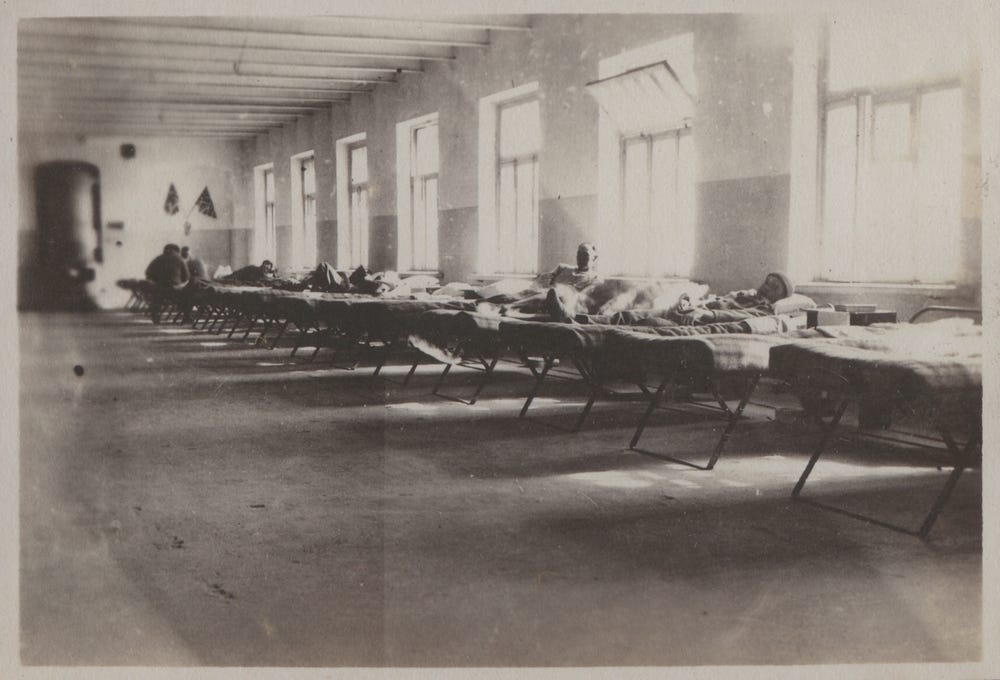

Of the nearly 5000 troops that ended up in Victoria, 1653 were conscripts, and very few were eager for the journey ahead of them. The condition in the camps they were stationed at was brutal, with the outbreak of the Spanish flu preventing public gatherings, outdoor training made impossible at times due to flooded fields from tremendous amounts of rain, and poor lodgings. Moreover, the Armistice announced on November 11, midway through the troops stay in Victoria, further sapped any morale to continue fighting, especially as half of those assembled had fought in Europe.

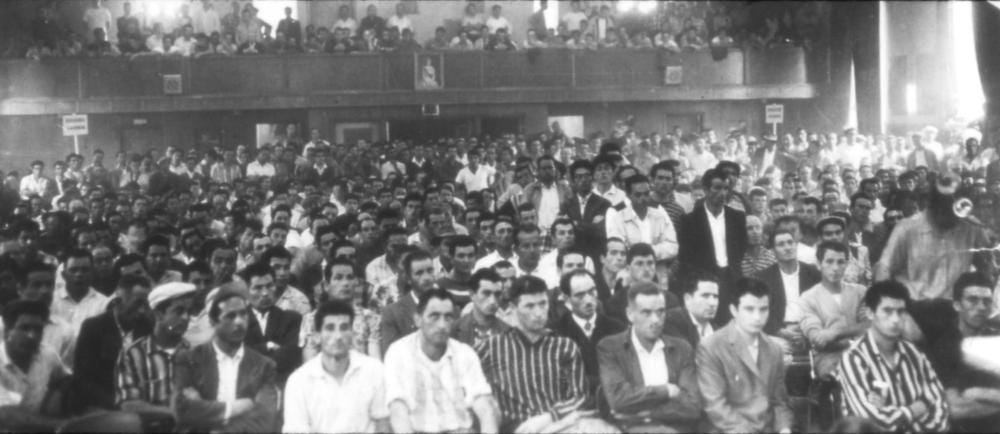

B.C. radicals seized upon this disaffection, and inundated the soldiers with propaganda, seeking to portray the expedition into Siberia as a war for the rich, at the expense of the poor. The labor radicals distributed leaflets to soldiers, and held several increasingly popular mass meetings where they called for “Hands off Russia.” On December 8, the Federated Labor Party held its inaugural meeting. Over 700 CEFS members attended, with hundreds more being turned away. On December 13, the Victoria Trades and Labor Council held another protest meeting, which was also well attended by CEFS troops.

The reaction from the troops at these meetings made it evident that they had little enthusiasm for the war. An article in the now defunct British Columbia Federationist newspaper said of the first meeting that “the way those boys applauded the Labor speakers showed in no uncertain manner where their sympathies lay.” Of the second meeting, the paper reported “the whole house, composed mostly of the Siberian contingent, were unanimous in expressing their sentiments to the withdrawal of the troops.”

The troops were also disgusted with their officers, who had stormed the stage at the December 13 meeting, singing “God Save the King” in an attempt to drown out the speakers. The budding unity between the soldiers and radicals caused such fear in the ruling class that B.C.’s lieutenant-governor, Frank S. Barnard, sent a letter to Borden asking him to bring battle cruisers on the shores, “if for no other reason, than for that of having a force to quell, if necessary, any rising upon the part of the IWW.”

This uprising didn’t come, but there was a mutiny launched by several troops on December 21, the day the first of the soldiers were to be deployed to Vladivostok. The men set to depart that day, from the 259th Battalion and 20th Machine Gun Company, had been prone to dissent since they were recruited. For a few days, there had been rumblings among them that they’d make a last ditch stand against their deployment.

Midway through their 3.5 mile march from the camp to the outer wharves, the troops stopped for a break. Several of them refused to get back in line when the whistle rang out, leading the colonel of the column to fire his gun over their heads, in the middle of the Victoria streets. This caused some of the men to get in line, but many still stood in their place. At this point, according to an account of the events from a lieutenant, published in the BC Federationist, “the other two companies from Ontario were ordered to take off their belts and whip the poor devils into line, and they did it with a will, and we proceeded.” The dissenters were then put under armed guard until they had boarded the boat. The lieutenant went on to write that “this company continued the march virtually at the point of the bayonet, they being far more closely guarded than any group of German prisoners I ever saw, and they were put under armed guard till we actually pulled out to sea, and even now a dozen of the ringleaders are in the cells — the two worst handcuffed together — awaiting trial.”

Canadian command tried their best to prevent news of the uprising from leaking out. Two days after the event, one of the CEFS commanding officers wired Ernest J. Chambers, Canada’s chief press censor, claiming the mutiny simply hadn’t occurred. Chambers then demanded all newspaper editors across the country suppress any news of the mutiny because it would “only cause unrest and bring discredit to our soldiers.” Letters from commanding officers, moreover, attempted to downplay the extent of dissent among the troops, portraying them simply as uneducated French-Canadians who were misled by “socialistic agitation.” Yet according to Isitt “these accounts distort the experience, and deny the agency, of British Columbia’s working class and simplify the motivations of the Quebecois troops themselves.”

Regardless, the mutiny was unsuccessful, as the men were shipped off the next morning, the first of the major deployments to Vladivostok. They arrived on January 12. The rest of the troops, deployed over the next month, arrived on January 15, and February 3, 18, and 27. The troubled CEFS had finally reached the shores of Vladivostok, but things only got worse.

The vast majority of Canadians never left Vladivostok, which one rifleman referred to as a “God forsaken hole,” throughout the entire time there. They saw little bloodshed, besides their ventures into the local red light district. One of the members of the CEFS, Captain Eric Elkington, wrote, “There was an awful place known as the ‘bucket of blood’ … where the troops would go in and there were just these sort of cubicles, and you could see the action which you liked best. Oh, that was the devil, trying to keep these lads away from that place.’” The problem became so severe, according to Isitt, that, “Between one-quarter and one-half of all Canadian hospital beds were occupied by patients with venereal disease, prompting the force command to threaten to ship afflicted troops back to Canada and to inform family members of the cause.” One of the men with the battalion was even shot in the penis by a sex worker.

Other than their sexual romps, Canadian troops played sports, held plays and concerts, and attended lectures. They also tried to help combat the rampant crime in Vladivostok where, according to a member of the CEFS, “It was said that one could have a man’s throat cut for a ruble.”

Just 50 troops got sent upcountry to Omsk, 3500 miles west of Vladivostok. The only action throughout the entire expedition was when a small group of Canadians, as well as Japanese, French, Italian, Czechoslovak, Chinese and White Russian soldiers, took a 14 mile trek to the town of Shkotovo, which had been attacked by partisans trying to free over 700 Bolshevik prisoners. When they arrived, according to Rifleman Harold Steele, there was only “one old man and a couple of women” left, as the Bolsheviks had already evacuated. There were only two injuries in the expedition: a French soldier accidentally shot a Japanese and Canadian soldier as he was testing his weapon.

The CEFS’ inaction was due in part to the mixed Allied strategy for how to combat the Bolsheviks and the dwindling confidence in the White Russian forces, but also the lack of support from even the governing class at home. After the Armistice was announced, acting Canadian Prime Minister Sir Thomas White begged Borden, who was on his way to the peace talks, to call off the CEFS. In the telegram, White wrote, “All our colleagues are of the opinion that public opinion here will not sustain us in continuing to send troops, many of whom are draftees under the Military Service Act and Order in Council, now that the war is ended.” On December 22, 1918, the Privy Council prevented the CEFS from being deployed up country, where the fighting was happening, due in part to public opinion. Then, in early January, a troopship planned to join the fight was cancelled, and the 85th Field Battery demobilized, due to “increasing popular opposition.”

This increase in anti-war sentiment was not a coincidence. Beyond merely radicalizing the soldiers in Victoria, Canada’s labor movement played a serious role in building the opposition to the war throughout the country. Labor councils in Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver, and Winnipeg, as well as labor federations of Alberta and B.C., announced their opposition to the CEFS. They were joined by machinist and railway worker AFL-affiliated union locals, who all worked to bring the public to their side.

On February 13, as pressure on the government continued to mount, Borden wrote to British Prime Minister Lloyd George, telling him the CEFS would return in early spring. Finally, on April 21, just four months after the first set of troops were deployed, departures began. Over the next six weeks, all of the troops would be sent home, on four different voyages. Many of the troops had been further radicalized there, including five of the Russian-born Canadian troops who deserted, and some stashed Bolshevik propaganda in their bags to distribute when they got home. In the end, 19 of the more than 4,000 troops who were sent to Vladivostok did not return. Sixteen of them died from disease, two from accidents on the journeys there and back, and one by suicide.

The CEFS was decried by some politicians back in Canada. In March 1919, before the troops had even come home, Dr. Hermas Deslauriers, a Member of Parliament (MP) for a Montreal riding, told a public meeting that the CEFS should “be considered a crime.” Canada’s trade commissioner to Vladivostok and first ambassador to the Soviet Union, Dana Wilgress, stated that the CEFS was “conceived as part of a concerted plan to overthrow the Communist regime that had seized power in Russia,” and as such, that it was a complete failure. On June 10, 1919, MP Henri Sévérin Béland told the House of Commons the CEFS was “a political error, a military mistake, and a wanton extravagance.” The CEFS has also since been harshly criticized by medical researchers who have labeled it as the “greatest single factor in the diffusion of [influenza],” with troops travelling across Canada infecting towns in their path “like an invading army ravaging a foreign country.”

The treatment of the men who launched the December 21 mutiny is another indicator of the admission of error by the ruling class. Forty of these men were initially arrested, and the ring leaders received sentences ranging from 28 days of field punishment to three years of hard labor, partially to deter other troops from expressing their mounting discontent. Yet in April 1919, as it became abundantly clear the CEFS was an error, all of the men who had been convicted were released on suspended sentences.

Yet while the CEFS was widely decried, and many of those who opposed it excused, the Canadian government did not see fighting communism as a mistake. They erred in execution, but believed the intended goal was noble. Their renewed battle began when the CEFS arrived back in Canada, as Isitt writes it “sharpened the divide between workers, employers, and the state, driving a section of workers into open sympathy with the Russian Bolsheviks.” Upon returning to Canadian shores, 150 Royal Northwest Mounted Police (RNWMP) Mounties were hit with a barrage of bricks and stones from longshoremen. Meanwhile, general strikes had broken out around the country.

Responding to these events, Borden: doubled the size of the militia meant to control these outbreaks to 10,000 troops; broke a general strike in Winnipeg with the army and RNWMP Mounties, leaving two dead and 50 injured; authorized broader RNWMP actions attempting to squash radicals across the country. Police powers were drastically broadened, dissidents were deported without trials, and the newly formed Royal Canadian Mounted Police quickly opened files on over 4,800 Canadians within 10 years.

The state also moved to erase the CEFS from collective Canadian consciousness. On October 17, 1919, a B.C. Federationist article presciently predicted that this history “never will be told if the ruling class of the Allied nations can prevent it.” World War One is commemorated by the Canadian state each year, yet little attention is ever given to the failed Siberian venture, which only makes up six pages of Canada’s official World War One history. Meanwhile, the Commonwealth portion of a cemetery in Vladivostok languished in squalor for decades, until 1996 when restoration efforts began.

This is tragic. Canadians deserve to be well acquainted with the CEFS, as its purpose is emblematic of wars in the following decades: motivated directly or indirectly by profit, for the ruling class at the expense of the poor sent to die, and in opposition to liberation movements across the globe. It is also a reminder that these efforts can be defeated.

Written by Davide Mastracci