The flower industry has a thorny environmental problem — and plastic is just part of it

Over the past few weeks, as a tribute to the late Queen Elizabeth, mourners laid hundreds of thousands of bouquets at royal residences and parks across the U.K.

As moving as some found it to see Buckingham Palace, Balmoral, Sandringham and Windsor Castle awash in a sea of floral tributes, others saw something else: plastic.

In central London's Green Park last Monday — one of many locations where people left flowers — workers bundled bags of discarded plastic wrappers and cellophane from bouquets left in honour of the Queen. In images posted in the Daily Mail, volunteers were seen cutting wrappers from bouquets, and a large flat-bed truck was stuffed with dozens of bags of the plastic waste.

Becky Feasby, a sustainable florist and owner of Prairie Girl Flowers in Calgary, said she had two thoughts when she saw the royal tributes. First, that the bulk of those flowers was likely imported. Second, she was struck by the "sheer volume of plastic wrapping."

"The amount of single-use plastic waste is truly staggering," said Feasby, who is also working on her master's degree in sustainability at Harvard University.

When thinking about harmful environmental practices, it might not seem obvious to consider the flower industry — which, after all, celebrates beautiful blooms grown of this earth.

"We think of them as gestures of kindness or empathy or affection," Feasby said. "But the reality of the global flower industry is that the bulk of our flowers are grown in the Global South and transported worldwide in refrigerated cargo jets and trucks, wrapped in plastic and arranged in toxic floral foam."

Depending on where the flowers come from, there's industrial farming and the effects of pesticides, fertilizers or water-hungry greenhouses to consider, said Kai Chan, a professor at the Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability at the University of British Columbia, and a Canada Research Chair in rewilding and social-ecological transformation.

"When people come to learn about just how damaging the industrial farming of flowers is, it doesn't feel like such a good gift," Chan said.

There's also the carbon footprint of importing exotic or out-of-season blooms — and quickly — to keep them fresh. Canada imported $137.8 million in cut flowers and buds for ornamental purposes in 2020, largely from Colombia, Ecuador, the U.S. and the Netherlands, according to Agriculture Canada's Statistical Overview of the Canadian Ornamental Industry.

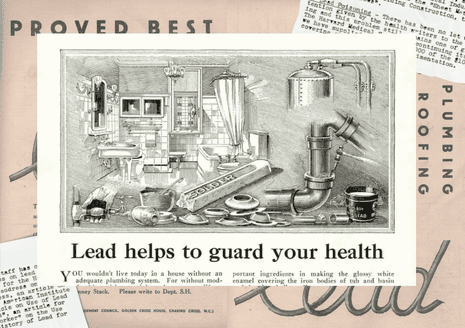

Then there's the packaging, which often includes the green floral foam that flowers are arranged in, and which has been shown to contribute to the world's microplastic pollution. Finally, wrap it all up in a plastic or cellophane sleeve.

Vancouver's MonteCristo magazine reports traditional floristry produces up to 100,000 tonnes of plastic waste each year.

Only nine per cent of plastic waste worldwide is actually recycled, with the bulk winding up in landfills, according to a 2022 OECD report. But the kind of wrapping used to package flowers is also light and flimsy, Chan noted, and thus likely to blow out of a landfill and into a nearby river, lake or ocean.

If you love fresh flowers — as a gift, a tribute or for yourself — there are plenty of ways to make environmentally friendly choices. Support for increased sustainability in the floral industry is increasing thanks to organizations such as the Sustainable Floristry Network and Slow Flowers, Feasby noted.

You can support locally grown, seasonal flower farmers, many of whom may use regenerative and organic growing practices. Look for florists who sell their bouquets in recycled paper or reusable glass vases.

This may mean buying your blooms from a local farmers' market or directly from a sustainable florist, and it may mean spending a little more money than you would at the grocery store checkout line, Chan said.

"It can still look beautiful, and it will be more meaningful. And arguably, that's the point."

As for the flowers that adorned the Queen's coffin during her funeral on Monday, they were local and meaningful: cut from the gardens of Buckingham Palace and Clarence House, they included myrtle grown from a sprig saved from the monarch's 1947 wedding bouquet.

— Natalie Stechyson