Sep 28, 2022Britain is in a self-inflicted financial crisis that threatens to accelerate the economy's dive into recession — and the country’s new prime minister is coming under intense pressure to blink.

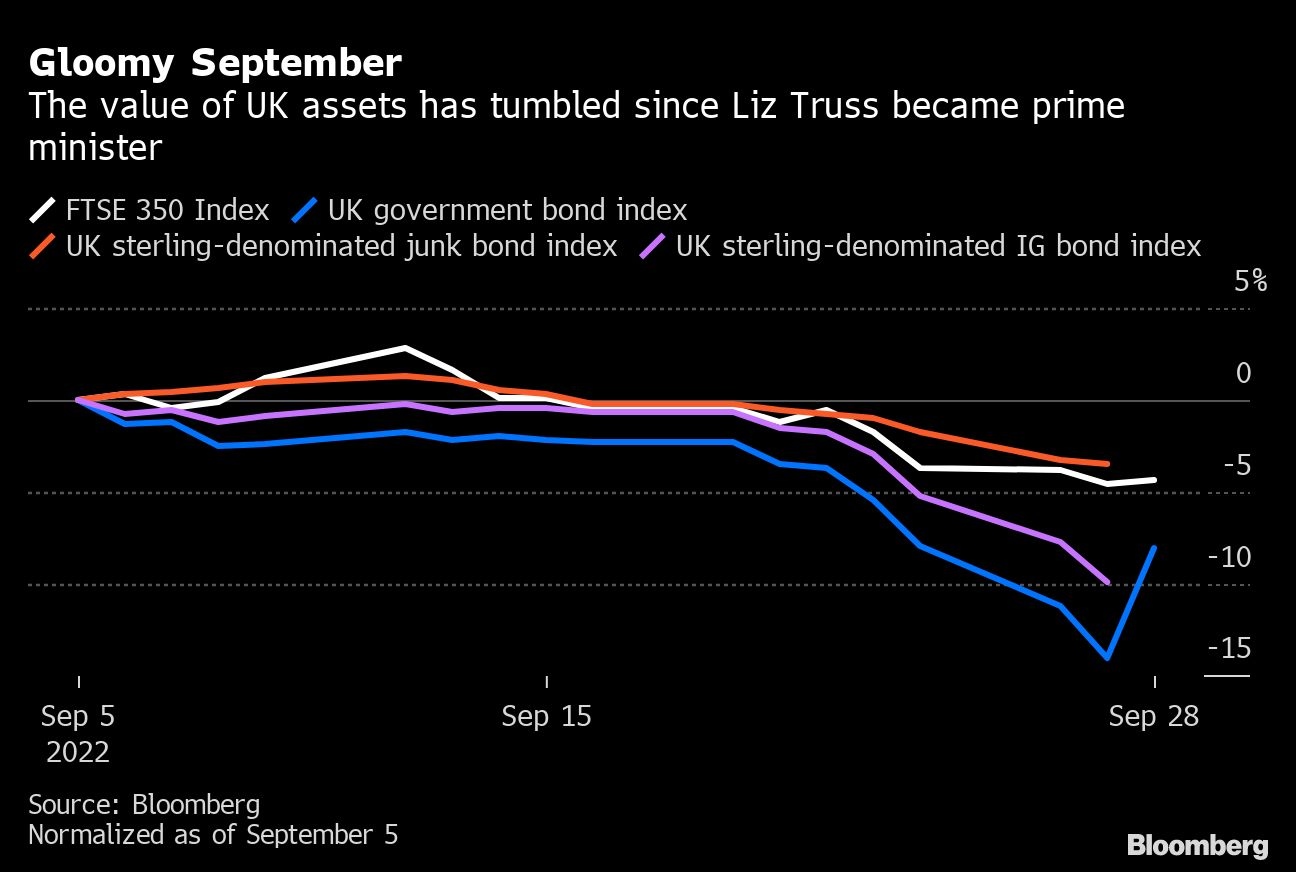

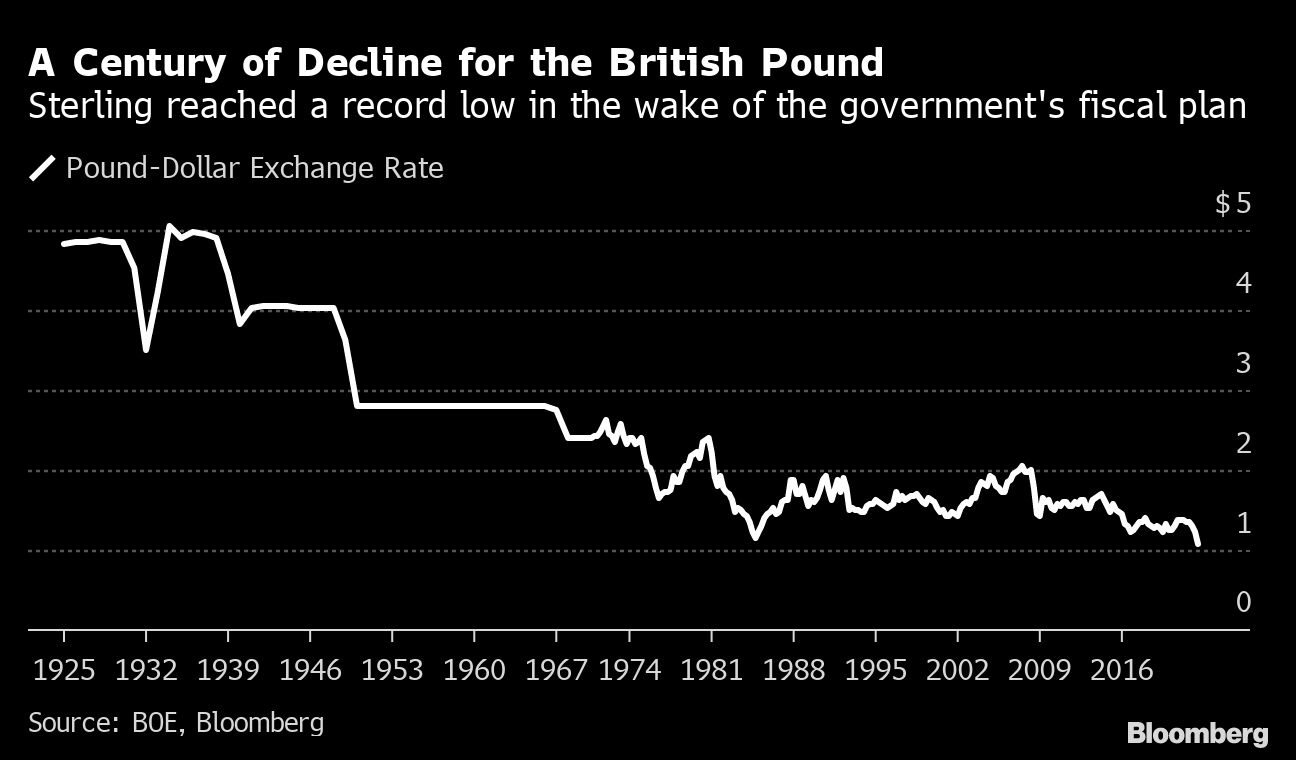

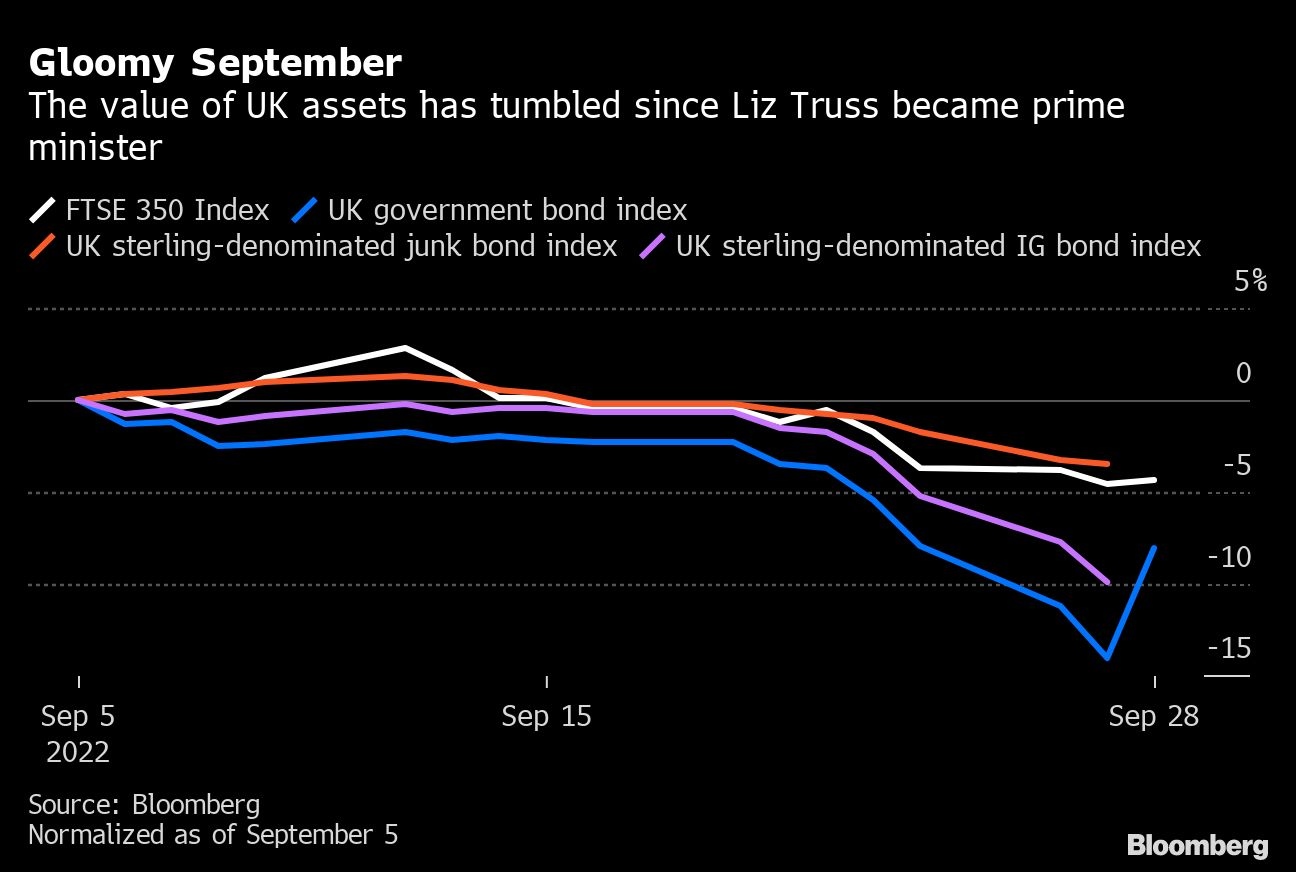

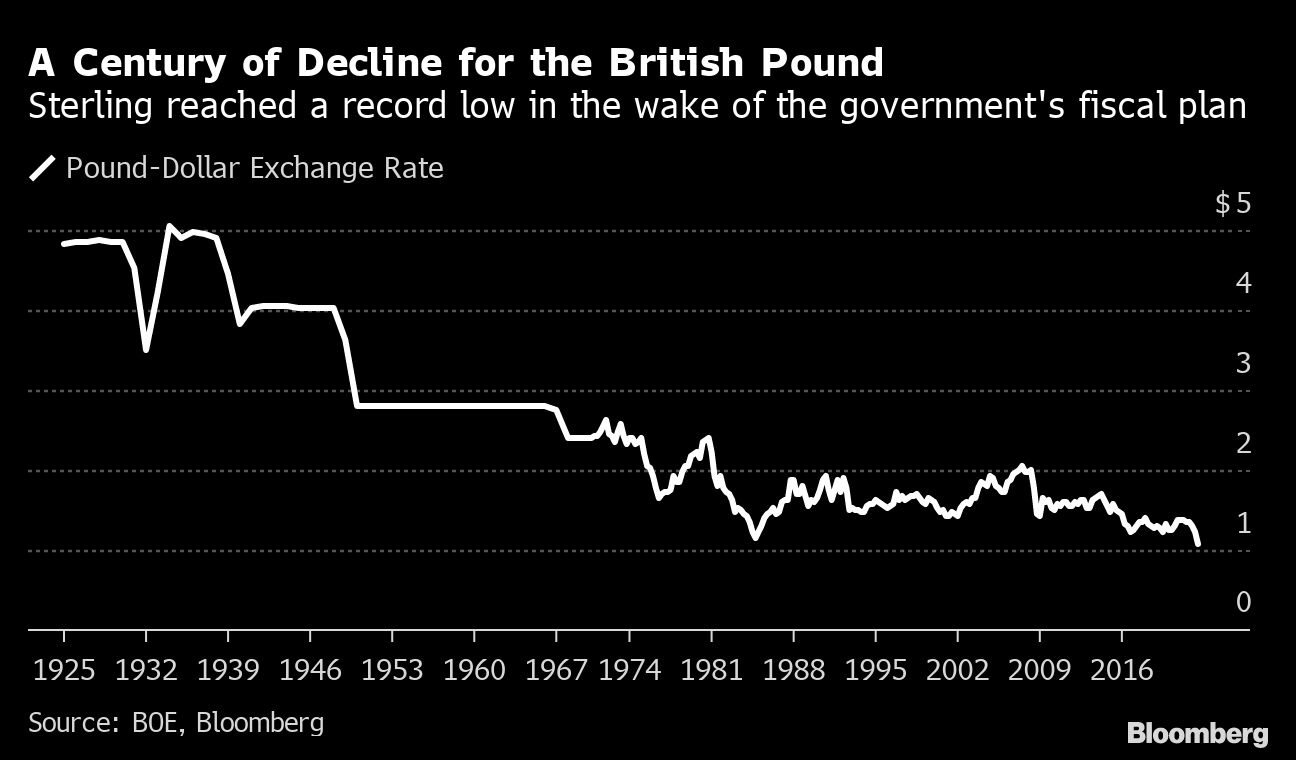

In the week since the government unveiled the biggest tax cuts since 1972 with scant detail of how they will be financed, the pound has crashed to its lowest-ever level against the dollar, the cost of insuring British government debt against the risk of default has soared to the highest since 2016, and the Bank of England has been forced to intervene amid concerns about the nation’s pension funds.

What happens next will determine just how deep the looming recession proves. Central to that question is whether Liz Truss’s three-week old administration can restore its credibility with investors.

Friday’s mini-budget has become a flashpoint for not just investors’ short-term concerns about unfunded tax cuts at a time when inflation is running close to a four-decade high, or the Bank of England’s failure to contain price growth. It has given sharp focus to their long-held fears about Britain, its current-account deficit, its fractious relationship with its closest trading partner and, above all, a mistrust of what successive politicians promise.

“It’s the latest in a long line of self-imposed economically illiterate decisions,” said Peter Kinsella, global head of FX strategy at Union Bancaire Privee UBP SA in London. “It started with Brexit, and now we’re seeing the latest iteration.”

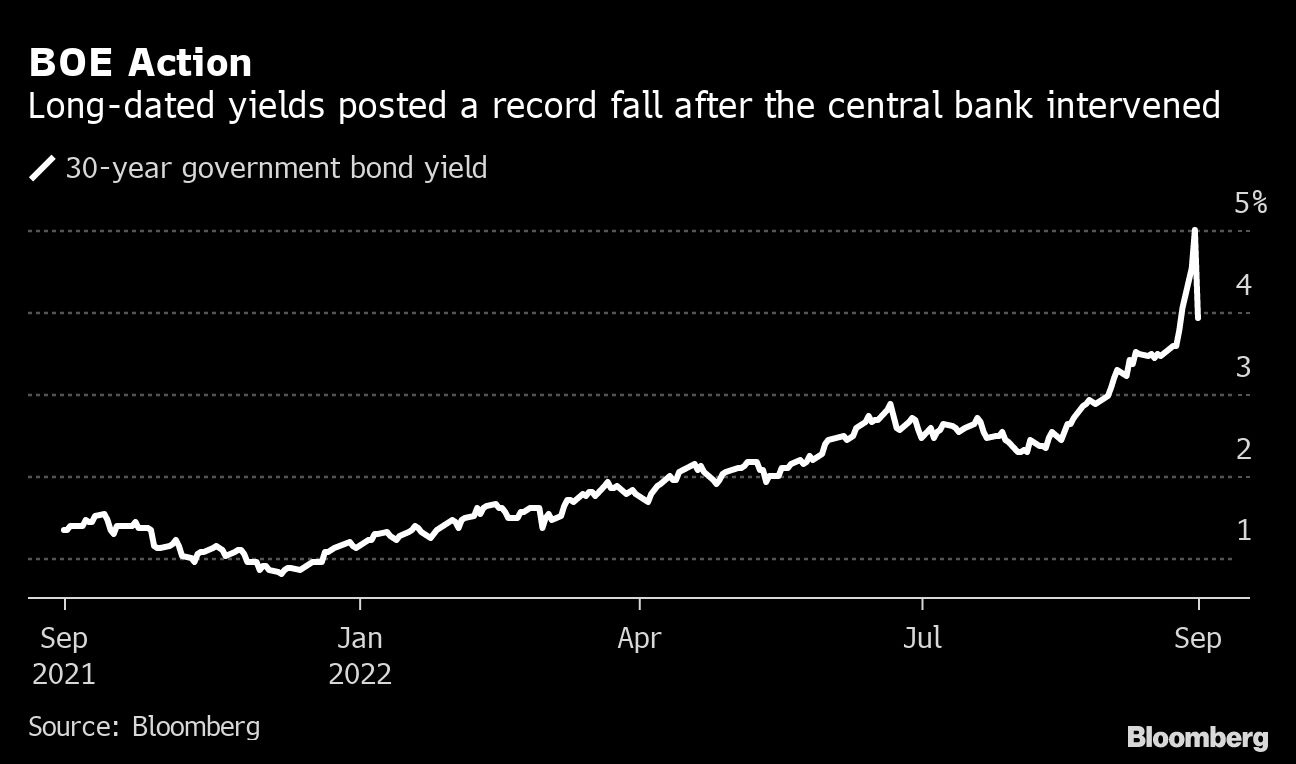

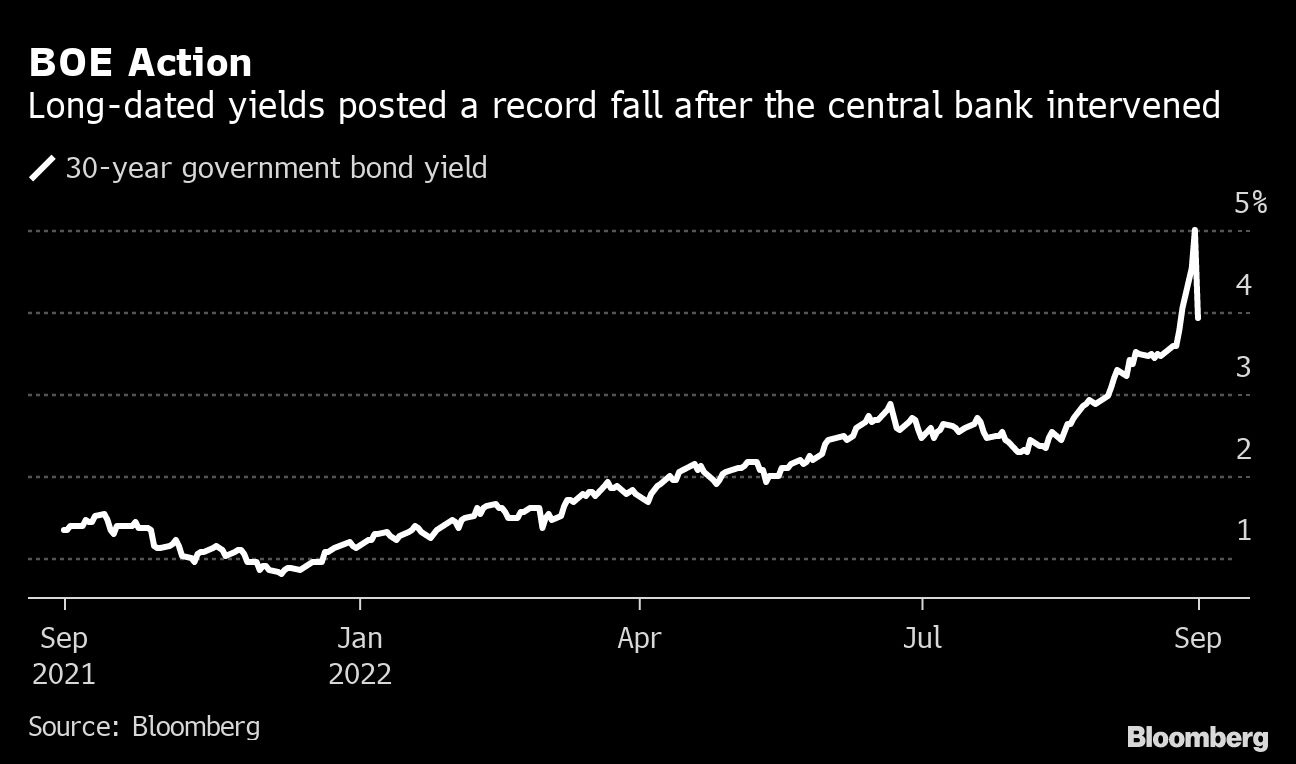

As markets tumbled, the Bank of England was forced into action to prevent a gilt market crash — and deployed a variant of a policy tool Truss spent recent months criticizing. It promised to buy whatever long-dated gilts were needed to restore order to the market. That set off a rally in long-dated gilts — but increases two risks: that the bank will have to raise rates even further within weeks, and that investors could take fright at whether the BOE is bankrolling the government.

For now, though, the BOE has bought the “government time to fix its credibility,” according to Kallum Pickering, senior economist at Berenberg Bank. How they use that time will be crucial.

Top bankers in the City of London yesterday urged Chancellor of the Exchequer Kwasi Kwarteng to reassure markets before a planned statement on Nov. 23.

The International Monetary Fund, which came to the UK’s rescue in 1976, has already called on the government to reconsider its tax cuts. Famed economists are lining up to warn the UK is displaying the hallmarks of an emerging market. Speaking to the BBC, former Bank of England Governor Mark Carney accused Truss’s government of “undercutting” the nation’s economic institutions.

The prime minister stood by her plans on Thursday, saying economies around the world are facing tough pressures.

“I’m very clear the government has done the right thing,” she told BBC local radio. “This is the right plan.”

The problem for Truss is that she made the tax cuts the centerpiece of her program for government. An about-turn so early into her tenure would be politically fatal: She only won office thanks to the backing of grassroots party members. Most MPs in her own party voted against her, leaving her exposed to a backlash if they sense her policies will lead to defeat.

While Britons wait to see if her gamble on “trickle-down” economics pays off, they face a dramatic increase in borrowing costs — something that could trigger a housing crash and deepen any recession — or a round of swingeing public spending cuts.

“Between Brexit, how far the Bank of England got behind the curve and now these fiscal policies, I think Britain will be remembered for having pursued the worst macroeconomic policies of any major country in a long time,” said former US Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers, now a professor at Harvard University and paid contributor to Bloomberg Television.

The crisis of confidence had been brewing for years. Dubious claims from the ruling Conservatives — ranging from Brexit’s benefits to parties in Downing Street during lockdown — together with the recent ousting of the Treasury’s top official and the side-lining of the country’s budget watchdog meant investors didn’t believe the Chancellor when he promised to stabilize the public finances.

The markets “aren’t willing to trust the Truss administration’s claims that it will deliver medium-term fiscal sustainability on the basis of its word alone,” said Allan Monks, an economist at JPMorgan Chase & Co. in London. “That reflects a broader distrust in markets about how UK policy making has been evolving — and in our view, that distrust is entirely justified.”

Nothing illustrates it better than the slide in the pound. It’s fallen from a high of more than US$2 in 2007, just before the financial crisis, to US$1.50 at the time of the Brexit referendum, and is now on the brink of parity with the dollar.

“Because the UK has damaged its once strong credibility with a poorly managed Brexit and persistent threats of a UK-EU trade war, it no longer enjoys the benefit of the doubt,” said Berenberg’s Pickering.

For JPMorgan’s Monks, the doubts set in before the 2016 Brexit referendum, accelerated after the shock result, and culminated in recent attacks on the central bank, the judiciary, and the civil service.

That background of mistrust may have obscured some of the mini-budget’s beneficial reforms. Simon French, chief economist at Panmure Gordon & Co., said the mishandling of the mini-budget was “a shame” because several of the supply-side reforms in areas like planning “have real merit.”

Nevertheless, Friday’s act of fiscal largess — being unfunded — marked a major break from the economic traditions of Truss’s Conservative Party. The government still needs to set out how it will cover the additional borrowing required to fund its £45 billion of tax cuts and further £60 billion-plus for its program to offset the recent surge in energy bills.

Those measures will drive up the country’s budget deficit to 4.5 per cent of gross domestic product in the medium term. That would be enough to put the debt burden on an explosive path, hitting 101 per cent of GDP by 2030, according to Bloomberg Economics.

In the meantime, the Bank of England will come under mounting pressure. The central bank has spent much of the year struggling to raise interest rates fast enough to combat a surge in inflation it failed to predict.

The BOE is now all but guaranteed to respond to the looser fiscal policy with tighter monetary policy. Money market traders are now betting on at least a 150 basis-point rise in interest rates by policymakers' next gathering on Nov. 3. Setting aside the risk of an emergency hike outside of scheduled meetings, that would be a move unprecedented since the bank was granted independence by the government in 1997. Pricing also shows the benchmark rate will almost certainly hit 6 per cent next year.

Companies and homeowners are now bracing for a steep increase in borrowing costs. The biggest British firms already face the highest cost on record to refinance their debt. The Resolution Foundation estimates that the additional increase in rates could add more than £1,000 to the annual cost of a typical £140,000 mortgage. Analysts at Credit Suisse Group AG estimate house prices could “easily” fall by as much as 15 per cent.

The UK, then, faces a grimmer outlook than what Truss promised in her summer campaign to succeed Boris Johnson, when she talked of upending the “business-as-usual economic strategy.” Her own survival in office is even in question. She faces an election in 2024 and one opinion poll this week showed the opposition Labour Party’s lead widening to 17 points, the most ever recorded by YouGov.

It’s not as if Truss wasn’t warned. While campaigning for the premiership over the summer, her opponent, former Chancellor Rishi Sunak, described her tax policies as a “fairy tale.” Economists at Citigroup Inc. even warned her ideas posed “the greatest risk from an economic perspective” to the UK.

One former Tory adviser, who asked not to be identified, was baffled by the decision to announce a mini-budget without a statement from the Office for Budget Responsibility. Not having an OBR forecast looked like a deliberate snub to the markets, he said, a sign that the government didn’t think it needed its sums to add up.

The last week has tested that confidence; the next could stretch it to breaking point.