Research redefines conversations around scarcity

The human experiences of living in poverty and living with scarcity go hand in hand. People living in poverty are forced to cope with critically low resources, and their scarce resources create unwelcome tradeoffs for them in areas such as housing, food, healthcare and other material needs on a daily basis.

Yet, if poverty and scarcity are truly intertwined in everyday life, why are they so often studied as different research topics? Why do important advances in the study of poverty and scarcity mostly develop among independent tribes of scholars that seldom share ideas or build on each other's work to create greater impact? Furthermore, why is the lens of resource scarcity mostly limited to understanding the experiences of relatively affluent people?

These nagging questions struck associate professor of marketing Chris Blocker and his colleagues midway through the pandemic. He and his colleagues—who are active in a multidisciplinary guild of scholars who address poverty—began probing these questions for answers. The group members' expertise range from sociologically-based qualitative research on consumer poverty to investigating human scarcity with experimental and psychological perspectives.

Together, they identified critical gaps in the ways that scarcity research examines the effects of extremely low resources for people living in poverty. Where Blocker and other poverty researchers often examine cultural insights into the enduring deprivations of poverty such as homelessness, scarcity researchers typically focus on point-in-time experiences of scarcity with people that have their basic needs met such as product availability challenges. There was clearly an opportunity to close the gaps by cross-pollinating ideas to create greater impact for people experiencing all kinds of scarcity.

"How could we bring these tribes exploring scarcity and poverty closer together?" Blocker said. "How might we integrate big ideas in ways that help researchers, policymakers and leaders studying scarcity and poverty speak each other's language? What frameworks can we create that draw on the robust findings from scarcity research but also are relevant for people who are actually experiencing significant material poverty?"

Ultimately, Blocker, CSU College of Business associate marketing professor Jonathan Zhang and their coauthors developed a new framework with dynamic extensions to bridge the areas of consumer poverty and scarcity. Their ideas offer future researchers the chance to jointly push scarcity and poverty research in new directions for greater impact. Their framework, "Rethinking Scarcity and Poverty: Building Bridges for Shared Insight and Impact," is published in the Journal of Consumer Psychology.

Building an integrated model of resource scarcity

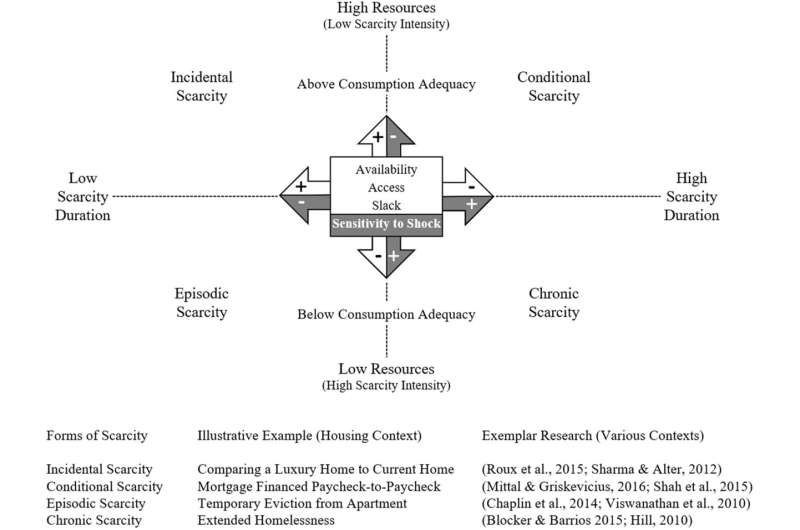

By constructing an integrated model of human scarcity and setting up a provocative research agenda, Blocker, Zhang and their coauthors address the differences between various disciplines' views on resource constraints to find common ground and build a structure that allows researchers to easily compare very different forms of scarcity. This required building a theoretical framework that addresses the many ways individuals experience resource shortages, classifying them by scarcity duration and scarcity intensity.

Some people experience scarcity for short periods, what the framework classifies as low duration, and with little disruptive effects on day-to-day existence—low intensity—a form of deprivation that Blocker, Zhang and their coauthors label incidental scarcity. People managing this type of scarcity aren't typically struggling to meet basic needs, and most of their brushes with scarcity don't disrupt their lifestyle. Examples of people facing incidental scarcity are shoppers who resort to alternative, but still sufficient, brands and products during supply chain shortages or people working long hours on a short-term project who struggle to find time to meet demands. People experiencing incidental scarcity are traditionally studied by scarcity researchers.

"In many cases, the participants within experimental scarcity research live well above what we call 'consumption adequacy,'" Blocker said. "They have their basic needs met, have jobs with health insurance and have a safety net of people that can support them in the event of significant setbacks."

Another classification in the framework, conditional scarcity, describes individuals experiencing low-impact scarcity over a long duration. These are individuals who possess what researchers term consumption adequacy—the ability to put a roof over their heads and food on the table—but who may be looking at strategies to extend their grocery bill or purchase items at thrift stores and are often living paycheck to paycheck. These are families who experience short-term unemployment of a parent, an unexpected expense that puts strain on their budget or other situational difficulty. Many people who experience conditional scarcity are on the bubble of economic distress but manage to live reasonably stable lives as long as their conditions don't change.

Should conditions worsen and those individuals lose access to thinly stretched resources, they may fall into a category the new framework characterizes as episodic scarcity. Their financial, time management, physical security or other resources are temporarily insufficient for consumption adequacy, and they may briefly be homeless or relying on other services to meet minimal needs. The impacts of scarcity are high and stressful for them, and they experience those effects intermittently.

Finally, chronic scarcity occurs when people experience highly intense scarcity for long periods and are continually unable to achieve consumption adequacy. These are people experiencing long-term homelessness, food insecurity, threats to their physical safety, and struggle to meet basic needs.

"People who are in episodic scarcity are constantly above and below consumption adequacy, and there's something unique about that uncertainty," Blocker explained. "People in chronic scarcity, they struggle to rebound. It's often rare that individuals are able to break out of certain cycles without extraordinary help."

Adjusting to shocks

The new framework also recognizes that people's lives impact how they experience and recover from economic and personal shocks that can trigger forms of scarcity. Instances such as a chronic illness, a layoff or an increase in rent introduce financial instabilities, and there is very little known about the differential effects of shocks—for example, a natural disaster—upon individuals with different levels of tangible and intangible slack. A person's ability to navigate shocks may also be a function of their ability to access help such as support services or the amount of grace that creditors, bosses and other members in one's social circle are willing to grant them.

Ultimately, this framework creates clarity around under-recognized concepts in scarcity and poverty research. It offers new research directions in which scarcity and poverty researchers can build on each other's work, and ultimately, it creates pathways for creative interventions and policy that helps lift people from chronic and episodic poverty.

"We are hopeful that by integrating models of scarcity, we can activate the tribes of scholars that are exploring these problems in new and impactful ways. Shared lenses and frameworks offer a catalyst for research to support people who are living impoverished lives and understanding the scarcity they experience," Blocker explains. "At the end of the day, policymakers working on poverty alleviation, businesspeople and researchers should work together to create solutions for real problems."Does water scarcity influence manufacturing firms to reduce toxic emissions?