Opinion: The Outer Space Treaty is 55 and out of date

Back in the 60s, the Outer Space Treaty provided us with an assurance of peace and security in the Cold War space race. So much has changed since then — so, why hasn't the Treaty — asks DW's Zulfikar Abbany.

Each time the USA planted a flag on the moon, it stuck a stake in the heart of the Outer Space Treaty

Consider the vastness of outer space for a moment and ask yourself whether it could or should be humanly possible to sum up all of what we humans may possibly want to do in outer space in a three-page document.

It certainly was possible in October 1967 — at least in an aspirational sense — when the Outer Space Treaty entered into force. But it shouldn't have been possible, not for a legal framework that's lasted 55 years ... and counting.

Our use of, and ambitions for, outer space have changed to such an extent in the past five decades that those three pages* just don't cut it anymore.

*I'm discounting the preamble and Articles XIII-XVII, which is largely legal jargon. (So, altogether it's more like seven pages. Big whoop.)

So, why do we have an Outer Space Treaty?

Back in 60s, we had two main players in space: the USA and the USSR. We were in a Cold War of ideologies, technology, world trade, resources, with battles for geographical domination on land, sea and in the skies. But not in space.

The Cold War could have bled into space, but the two superpowers made a pledge to keep outer space free of military conflict. Plus, we had enough other battles to be getting on with on the ground — Vietnam, to name the most obvious. They reserved outer space for exploration, science, and described it as "the province of all mankind."

But they had all this rocket science left over from World War II, so why not use it — blast a few humans into space and plant a flag? Why not? Well, by planting their flag on the moon, the USA rammed a stake into the Treaty's heart. That's why.

Race through the Apollo years and you could argue that without the Outer Space Treaty, we wouldn't have had 20+ years of wonderful collaboration on the International Space Station.

Article V states that "Parties to the Treaty shall regard astronauts as envoys of mankind in outer space and shall render to them all possible assistance ..." — it's talking about helping astronauts when they return to Earth.

The spirit of those words were seen in action in the early months of the ongoing Russia-Ukraine War when Russia could very well have left NASA astronaut Mark Vande Hei stranded on the ISS, but, instead, allowed him to return to Earth onboard a Russian-built Soyuz spacecraft alongside two Russian cosmonauts.

So, all good there. But spirit and goodwill won't see us through much longer. Things have changed too much since 1967.

There have been numerous other space treaties alongside, if you will allow me to paraphrase a space debris expert at the European Space Agency, "unenforceable" guidelines. But the Outer Space Treaty remains the foundation, like a ceremonial constitution, upon which all other space law is draped.

The problem is that the Treaty is vague and itself virtually unenforceable.

I've spoken to outer space experts who celebrate the Treaty for its vagueness — "that's what makes it so adaptable," they say — and I've spoken to space lawyers who agree that the Treaty is an anachronism and that it needs to go — for the very same reason.

The problem with the Outer Space Treaty

Perhaps the Treaty is not entirely at fault — perhaps it's the times in which we live.

In the 60s, who could have predicted that we would have thousands of active satellites orbiting our planet, each under threat from 10 times as many bits of space debris — each tiny rock vying to knock out our increasingly essential global communication networks. Satellites are moved by controllers on Earth to dodge space debris more regularly than I care to look up right now.

Who would have thought that we would see China progress on the moon and other "celestial bodies" like asteroids, where all other nations have failed. China was the first country to land on the far side of the moon, but you would never have thought it in the 60s.

It is also, along with Japan, a pioneer in what scientists call "sample return missions" — robotic retrievals of rocks and minerals that we all need for our survival on Earth.

And who would have predicted that some of the newer players in space, India among them, would be quite happy to fire rockets from Earth to shoot their own satellites out of orbit — even though the Outer Space Treaty prohibits it.

The DART mission: It's about protecting Earth from asteroids, but who is to stop the same

technology being used to attack a country's space interests?

Article IV refers to celestial bodies when it says that "the testing of any type of weapons ... shall be forbidden," but it's a short step from shooting your own satellite to shooting someone else's, or ramming an asteroid with a space craft (read, NASA's recent DART mission) ...

All research and innovation is adaptable for both good and bad, and "all of mankind" has shown so many times how we just love to adapt good stuff to do bad.

Who could have predicted it? We all could have predicted it.

But we can salvage the Treaty

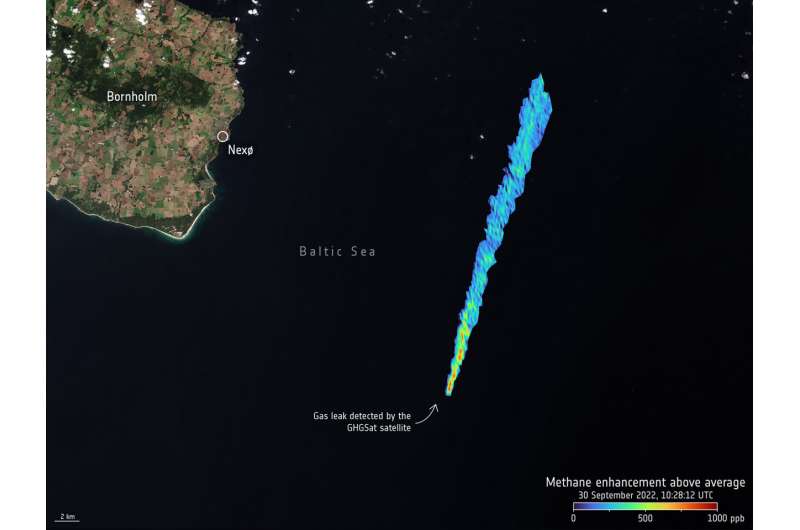

We can still turn this around. We can work harder to encourage countries like China to accept "international responsibility" when their rockets — turned space junk — fall back to Earth, landing in and polluting our oceans.

Articles X and XI of the Treaty allude to equality and the sharing of information. And we can improve transparency about our ambitions for space. We can build on Earth observation programs that truly aim to benefit all people in our climate emergency.

There is, however, one thing we can't fix and that is the 60s pipedream that we could ever have managed to maintain peace in outer space. The USA officially considers space another dominion of war, so, Russia would be stupid not to. And as we can see on our screens, those old foes are still old foes. So, given how we struggle to observe international law on Earth, especially in war, what chance have we got it space?

Edited by: J. Wingard

DW RECOMMENDS

- Date 10.10.2022