PM Sunak faces a very different economy to the one he left as chancellor

By Alan Shipman, Senior Lecturer in Economics, The Open University

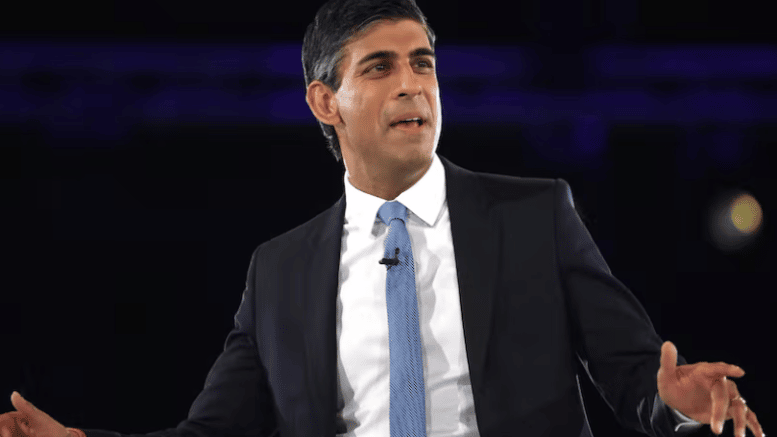

As the incoming UK prime minister, Rishi Sunak has the immediate advantage of perceived success in his two years as chancellor. His tenure ended last July when he resigned due to a difference of opinion with then-prime minister Boris Johnson over the economy. But during his time as chancellor, he is credited with rescuing households and businesses from the effects of the COVID pandemic lockdowns by launching an innovative and impressively timely furlough scheme. He reversed a “small state” approach to become the private sector’s temporary paymaster, spending an unprecedented £70 billion to shorten the recession.

This image of having saved the nation by minimising the loss of national output and employment during the pandemic has outshone the less successful moments of his chancellorship. This includes inadequate fraud-proofing of furlough supports, the coronavirus surge that followed his “eat out to help out” hospitality revival scheme and the discussion of his well-sheltered family finances.

But as he takes up the UK’s highest office, the economic supports that enabled the furlough scheme have largely fallen away. The government’s long-term borrowing costs, previously close to zero, had risen above 5% by mid-October, even with the Bank of England shoring up demand to keep bond yields down. At the same time, consumer borrowing has also risen in cost, dowsing any hope of a post-pandemic bounce-back of growth-promoting investment.

The UK now faces a worsening credit rating, which is adding to the risk premium (and therefore cost) that investors place on public debt. And consumers are unlikely to spend their way out of the expected recession. Millions are already struggling to meet rising food, fuel and mortgage bills, knowing their energy costs could jump again when the current price cap ends in April 2023.

In the US, where Sunak earned his MBA and made his fortune, post-crisis presidents are often seen as “Lone Ranger” figures. They ride into town (with a masked companion) to resolve a desperate situation, winning over an initially sceptical public with effective steps that overcome past rivalries and injustices.

Contemporary American Conservatives have emphasised additional plot twists: the Ranger must overcome prejudices and sidestep rigid laws to save the day. This certainly speaks to the task ahead for Sunak as he becomes the fifth UK prime minister in six years.

Staggering under stagflation

Unusually, UK firms are experiencing widespread labour shortages right now, among other supply constraints that usually characterise the peak of a boom rather than the brink of a recession. That’s down to the decade-long stagnation of UK labour productivity. This is a problem that Sunak as a backbencher wanted to tackle with doses of deregulation and labour-market discipline, but which as chancellor he left unresolved.

Productivity growth picked up after the UK propelled the EU to complete its single market from 1992. So Sunak’s support for leaving the EU remains an obstacle to his re-uniting the Conservatives and rebuilding badly burnt bridges with European trade partners. Their importance has been heightened by the declining chance of any transatlantic trade deal and the slowdown in the Chinese economy, which will dampen growth across emerging Asia.

So what’s a new prime minister to do? Having resigned from the cabinet in July, triggering the very Conservative infighting that has now led him to the top job, Sunak can leave the difficult fiscal choices to Jeremy Hunt, his successor as chancellor. But the prime minister still bears ultimate responsibility for the direction the government takes to deal with the economy. Hunt’s statements so far have rescinded most of Kwasi Kwarteng’s mini-budget, indicating that the new government has no room for tax reduction and could be preparing for more painful cuts in public spending instead.

If Hunt sticks to the Conversatives’ election-winning 2019 pledge of no rises in income tax, VAT or national insurance, the government will probably need to deploy “stealth taxes”. This means leaving working people to be taxed more as their wages rise to keep pace with prices while a four-year freeze in tax thresholds imposed by Sunak is still in place. Social benefits could also be allowed to erode through being raised by less than inflation.

The present high rate of inflation would also, in the past, have eased the government’s financial pressures by eroding the costs of public and private debt. But that shield has worn thin. Payments on 25% of the government’s debt are now aligned with the inflation rate, and lenders are rapidly passing on the rise in borrowing costs to mortgage and credit card borrowers.

Former prime minister David Cameron could cite an outgoing Labour government’s budget hole for earlier austerity rounds. But Sunak will struggle to blame his predecessors for the new fiscal squeeze the UK faces. Supporters of Kwarteng are likely to continually remind him – as ex-prime minister Liz Truss did on her way to beating him in the previous leadership contest – that tightening fiscal policy now will only deepen the recession predicted by the Bank of England and many independent analysts.

The rescuer from Number 11 must become “Austerity Rishi” now he’s moved next door. This could make it far more difficult for the Lone Ranger to ride into the sunset after saving the day.