THE ORIGIN OF CHRISTIAN NATIONALISM

Poll: Nearly half of Americans think the US should be a Christian nation

But those who say that tend to avoid hard-line positions and have different views about what a Christian nation should look like.

(RNS) — Forty-five percent of Americans believe the U.S. should be a “Christian nation,” one of several striking findings from a sweeping new Pew Research Center survey examining Christian nationalism.

But researchers say respondents differed greatly when it came to outlining what a Christian nation should look like, suggesting a wide spectrum of beliefs.

“There are a lot of Americans — 45% — who tell us they think the United States should be a Christian nation. That is a lot of people,” Greg Smith, one of the lead authors of the survey, said in an interview. “(But) what people mean when they say they think the U.S. should be a Christian nation is really quite nuanced.”

The findings, unveiled Thursday (Oct. 27), come as Christian nationalism has become a trending topic in midterm election campaigns, with extremists and even members of Congress such as Georgia Republican Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene identifying with the term and others, such as Rep. Lauren Boebert of Colorado and Pennsylvania Republican gubernatorial candidate Doug Mastriano, expressing open hostility to the separation of church and state. In the road show known as the ReAwaken America Tour, unapologetically Christian nationalist leaders crisscross the country spouting conspiracy theories and baptizing people.

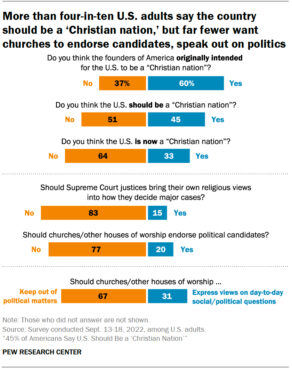

“More than four-in-ten U.S. adults say the country should be a ‘Christian nation,’ but far fewer want churches to endorse candidates, speak out on politics” Graphic courtesy of Pew Research Center

Pew’s findings suggest the recent surge in attention paid to Christian nationalism has had an effect on Americans, although some suggested politicians may be staking out positions to the right of those who merely say America should be a “Christian nation.”

“I used to think it was a positive view, but now with the MAGA crowd, I view it as racist, homophobic, anti-woman,” read one response to the question, according to the report.

According to the survey, which was conducted in September, 60% of Americans believe the U.S. was originally intended to be a Christian nation, but only 33% say it remains so today. Most (67%) say churches and other houses of worship should keep out of political matters, with only 31% endorsing faith groups’ expressing views on social and political issues.

Even those who believe America should be a Christian nation generally avoided hard-line positions. Most of this group (52%) said the government should never declare any particular faith the official state religion. Only 28% said they wanted Christianity recognized as the country’s official faith. Similarly, 52% said the government should advocate for moral values shared by several religions, compared with 24% who said it should advocate for Christian values alone.

But the pro-Christian America group was more split on the separation of church and state: 39% said the principle should be enforced, whereas 31% said the government should abandon it. An additional 30% disliked either option, refused to say or didn’t know.

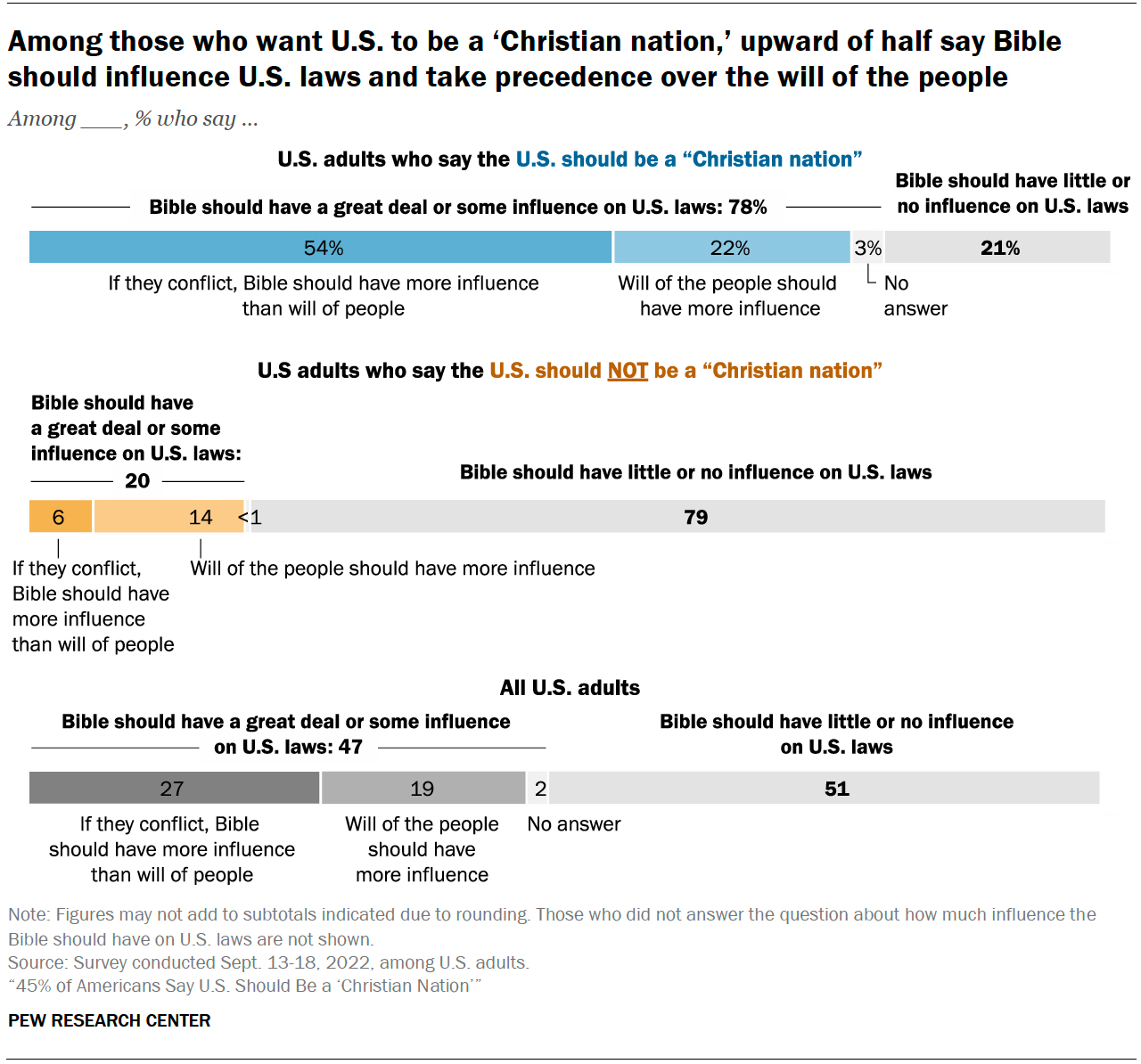

Most in the group (54%) also said that if the Bible and U.S. laws conflict, Scripture should have more influence than the will of the people.

“Among those who want U.S. to be a ‘Christian nation,’ upward of half say Bible should influence U.S. laws and take precedence over the will of the people” Graphic courtesy of Pew Research Center

Smith stressed that some respondents who expressed support for a Christian nation “do mean that they think Christian beliefs, values and morality ought to be reflected in U.S. laws and policies.” But many respondents “tell us that they think the U.S. should be guided by Christian principles in a general way, but they don’t mean that we should live in a theocracy,” he said. “They don’t mean that they want to get rid of separation of church and state. They don’t mean they want to see the U.S. officially declared to be a Christian nation. It’s a nuanced picture.”

Among U.S. adults overall, only a small subset believe the U.S. government should declare Christianity the national faith (15%), advocate for Christian values (13%) or stop enforcing the separation of church and state (19%).

Partisanship strongly shaped the responses, with those who are Republican or lean toward the GOP far more likely to say America should be a Christian nation (67%) than Democrats or Democratic leaners (29%). Republicans were also significantly more likely to say the founders intended the country to be a Christian nation (76%), although nearly half of Democrats agreed (47%).

These divisions appear to reflect national political trends. While Democratic lawmakers — especially members of the Congressional Freethought Caucus — have voiced concerns about Christian nationalism’s role in the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol, many congressional Republicans have declined to condemn the ideology, with only a small number affirming support for the separation of church and state.

The outsized presence of white evangelicals in the GOP may play a role. In Pew’s survey, white evangelicals were the faith group most likely to say America should be a Christian nation (81%). But they were followed by Black Protestants (65%), a heavily Democratic group. White nonevangelical Protestants were more split, with 54% agreeing the U.S. should be a Christian nation.

Photo by Aaron Burden/Unsplash/Creative Commons

Catholics were the only major Christian group where a majority did not express support of the idea (47%) of a Christian nation, though they were split along racial lines: Most white Catholics (56%) agreed America should be a Christian nation, while Hispanic Catholics were the least likely of any Christian group to say the same (36%).

Few Jewish (16%) or religiously unaffiliated Americans (17%) thought the U.S. should be a Christian nation, followed by an even smaller subset of atheists and agnostics (7%).

Age is also a factor. Among Americans ages 65 or older, 63% said America should be a Christian nation, compared with 23% of 18- to 29-year-olds.

Pew asked half of respondents to define a “Christian nation” in their own words and used their open-ended answers to group most people into three categories: those who see it as general guidance of Christian beliefs and values in society (34%); those who see it as being guided by beliefs and values, but without specifically referencing God or Christian concepts (12%); and those who see it as having Christian-based laws and governance (18%).

Those who think the U.S. should not be a Christian nation were more likely to describe a Christian nation as having Christian-based laws and governance (30%) than did those who believe it should be (6%).

The survey polled the other half of respondents about their views on Christian nationalism. Among all U.S. adults, fewer than half (45%) said they had heard anything about the term. Non-Christians were more likely than Christians overall to have heard or read anything about Christian nationalism (55% vs. 40%), and Democrats were more likely to express familiarity than Republicans (55% vs. 37%).

But researchers noted that while 54% of those surveyed said they hadn’t heard of Christian nationalism, respondents overall were far more likely to view the concept unfavorably (24%) than favorably (5%), suggesting that people familiar with the concept generally view it negatively.

As Christian nationalism digs in, differing visions surface

As Christian nationalists get more specific, ideological and theological divisions have reemerged.

WASHINGTON (RNS) — When Tennessee Pastor Greg Locke took the stage at the ReAwaken America Tour in Pennsylvania over the weekend, the throngs who had come out to hear conspiracy theories and inflammatory rhetoric about Democratic candidates instead heard Locke aim some of his sharpest criticism at a surprising target: Pope Francis.

“If you trust anybody but Jesus to get you to heaven, you ain’t going,” Locke said, his voice rising. “You say, ‘Well what about the pope?’ He ain’t a pope, he’s a pimp … He has prostituted the church.”

It was an odd note to strike at a rally where perhaps the biggest name on the speaker’s roster was retired Gen. Michael Flynn, a Catholic who later made it a point to mention his faith while voicing support for Christian nationalism. “I’m a Christian — I’m a Catholic, by the way,” said Flynn.

Former Trump national security adviser Michael Flynn speaks Nov. 13, 2021, at Cornerstone Church in San Antonio. Video screen grab

Locke had aired his anti-Catholic position a few days before in a Facebook post advocating for burning rosaries and “Catholic statues.” When another user urged him to abandon the anti-Catholic rhetoric, Locke doubled down. “Catholicism is idolatry 100%” he wrote. “I will not be silent whether you follow or not. It’s a false pagan religion and so filled with perversity it’s ridiculous.”

Anti-Catholic rhetoric has long been a theme in nativist American thought, which includes some forms of extremist Protestant Christian agitators such as the Ku Klux Klan. But in the current Christian nationalist surge that fuels the ReAwaken gatherings and others like it, the ideology has served more as a glue holding together a wide range of right-wing coalitions. Locke’s remarks injected an uneasy tension, raising the prospect that what was once a unifying force is now prone to causing potential divisions in right-wing ranks.

The theological differences among the hardline Christian nationalist groups — some now emboldened to the point of embracing the Christian nationalist label — have been present from the start. Texas Pastor Robert Jeffress, who rose to national prominence as an early supporter of then-candidate Donald Trump, is an ardent purveyor of Christian nationalism. As far back as 2018, Jeffress preached an Independence Day-themed homily titled “America is a Christian nation,” and he now sells a book of the same name.

Before then, the pastor was known for railing against the Catholic Church. In 2010 he argued it was little more than a “cult-like, pagan religion,” adding, “isn’t that the genius of Satan?” A year later, he also decried the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as a “cult” and a “false religion.”

But Jeffress and other faith leaders’ sectarian rhetoric faded as they made common cause in support for the president. After Trump was voted out of office, Catholics and conservative Protestants were unified in the Stop the Steal movement. By the time the movement culminated in the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol, a curious form of Trumpian ecumenism had taken hold, as rioters of several faiths prayed together as they led the assault.

In the aftermath of Jan. 6, several types of extremists gravitated toward Christian nationalism and claimed it as their own, some linking it to opposition to pandemic restrictions, masks and vaccines and others incorporating the ideology into attacks on LGBTQ people.

But within this cohort, the different variants of Christian nationalism began to show themselves and develop. Even as Locke was becoming a major Christian nationalist voice, Nick Fuentes, the white nationalist head of the group America First, and a Catholic, was on the rise as well. While Locke has advocated for burning rosaries, Fuentes has celebrated the idea of “Catholic Taliban rule.”

Meanwhile, Andrew Torba, the head of the alternative social media website Gab, which has been widely shamed for sharing antisemitic messages, has presented in a new book another form of Christian nationalism, one that rails against groups that center on End Times theology — particularly the belief that the Second Coming is imminent. Torba and his co-author refer to these ideas as “an eschatology of defeat” and blame their advocates for a moral decline of society.

“You cannot simultaneously hope for a revival of Christian faithfulness in our nation while expecting the world to end at any moment,” Torba and his coauthor wrote.

Torba’s critique is not likely to go down well with various evangelical, Pentecostal and Charismatic traditions that have made the End Times central to their message, among them Trump’s biggest supporters. Jeffress has published two books focused on the topic — “Countdown to the Apocalypse” and “Twilight’s Last Gleaming.”

FILE – Rep. Lauren Boebert, R-Colo., speaks at a news conference held by members of the House Freedom Caucus on Capitol Hill in Washington, on July 29, 2021. Boebert has spoken by phone with Rep. Ilhan Omar, D-Minn., just days after likening her to a bomb-carrying terrorist. By both lawmakers’ accounts, the call on Nov. 29, 2021, did not go well. (AP Photo/Andrew Harnik, File)

Rep. Lauren Boebert, who made headlines earlier this year for arguing against the separation of church and state, also outlined support for the theology in a recent speech.

“Many of us in this room believe that we are in the last of the last days,” she told attendees at a Republican dinner in Tennessee. “You get to be a part of ushering in the second coming of Jesus.”

These differences are unlikely to affect the Christian nationalists’ common front immediately or slow their approach to the coming elections. Hardline Christian nationalists across the ideological spectrum are more apt to focus on Democratic candidates and their supporters as a common enemy. Nor are figures such as Locke likely to topple a conservative Christian coalition that dates back to the 1970s, when a truce was struck between the likes of Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell and the anti-abortion Catholic right.

If Trump runs for reelection in 2024, it’s likely many who trumpet Christian nationalism will simply set their differences aside — just as they did the last two times he ran for office.

But with many on the extreme right distancing themselves from Trump, and the pandemic and COVID-19 vaccinations no longer making the headlines they once were, the faithful who are drawn to rallies such as ReAwaken America may encounter new fissures as they debate new causes to rally behind — or against. Some Christian nationalist voices, such as Jeffress, have already peeled off. “There is no legitimate faith-based reason for refusing to take the vaccine,” the pastor told the Associated Press last year. He also declined to argue that the 2020 election was “stolen,” a common refrain among many right-wing Christian nationalists.

And even if attendees and speakers at the ReAwaken America tour write off pastors like Jeffress, a question remains: How long will Catholics like Flynn abide attacks on their faith from even their most stalwart Protestant collaborators?