The Conversation

November 11, 2022

The Sun (Shutterstock)

There’s an awkward, irksome problem with our understanding of nature’s laws which physicists have been trying to explain for decades. It’s about electromagnetism, the law of how atoms and light interact, which explains everything from why you don’t fall through the floor to why the sky is blue.

Our theory of electromagnetism is arguably the best physical theory humans have ever made – but it has no answer for why electromagnetism is as strong as it is. Only experiments can tell you electromagnetism’s strength, which is measured by a number called α (aka alpha, or the fine-structure constant).

The American physicist Richard Feynman, who helped come up with the theory, called this “one of the greatest damn mysteries of physics” and urged physicists to “put this number up on their wall and worry about it”.

In research just published in Science, we decided to test whether α is the same in different places within our galaxy by studying stars that are almost identical twins of our Sun. If α is different in different places, it might help us find the ultimate theory, not just of electromagnetism, but of all nature’s laws together – the “theory of everything”.

We want to break our favorite theory

Physicists really want one thing: a situation where our current understanding of physics breaks down. New physics. A signal that cannot be explained by current theories. A sign-post for the theory of everything.

To find it, they might wait deep underground in a gold mine for particles of dark matter to collide with a special crystal. Or they might carefully tend the world’s best atomic clocks for years to see if they tell slightly different time. Or smash protons together at (nearly) the speed of light in the 27-km ring of the Large Hadron Collider.

The trouble is, it’s hard to know where to look. Our current theories can’t guide us.

Of course, we look in laboratories on Earth, where it’s easiest to search thoroughly and most precisely. But that’s a bit like the drunk only searching for his lost keys under a lamp-post when, actually, he might have lost them on the other side of the road, somewhere in a dark corner.

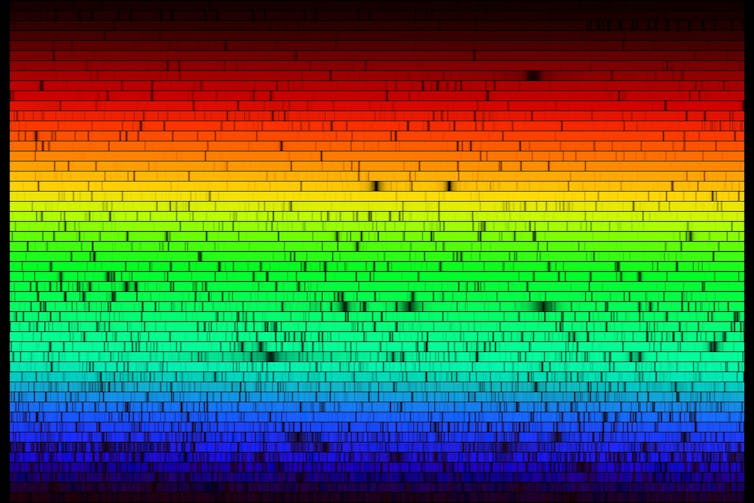

The Sun’s rainbow: sunlight is here spread into separate rows, each covering just a small range of colors, to reveal the many dark absorption lines from atoms in the Sun’s atmosphere.

We decided to look beyond Earth, beyond our Solar System, to see if stars which are nearly identical twins of our Sun produce the same rainbow of colors. Atoms in the atmospheres of stars absorb some of the light struggling outwards from the nuclear furnaces in their cores.

Only certain colors are absorbed, leaving dark lines in the rainbow. Those absorbed colors are determined by α – so measuring the dark lines very carefully also lets us measure α.

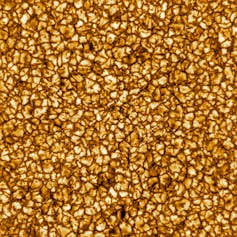

Hotter and cooler gas bubbling through the turbulent atmospheres of stars make it hard to compare absorption lines in stars with those seen in laboratory experiments.

The problem is, the atmospheres of stars are moving – boiling, spinning, looping, burping – and this shifts the lines. The shifts spoil any comparison with the same lines in laboratories on Earth, and hence any chance of measuring α. Stars, it seems, are terrible places to test electromagnetism.

But we wondered: if you find stars that are very similar – twins of each other – maybe their dark, absorbed colors are similar as well. So instead of comparing stars to laboratories on Earth, we compared twins of our Sun to each other.

A new test with solar twins

Our team of student, postdoctoral and senior researchers, at Swinburne University of Technology and the University of New South Wales, measured the spacing between pairs of absorption lines in our Sun and 16 “solar twins” – stars almost indistinguishable from our Sun.

The rainbows from these stars were observed on the 3.6-meter European Southern Observatory (ESO) telescope in Chile. While not the largest telescope in the world, the light it collects is fed into probably the best-controlled, best-understood spectrograph: HARPS. This separates the light into its colors, revealing the detailed pattern of dark lines.

HARPS spends much of its time observing Sun-like stars to search for planets. Handily, this provided a treasure trove of exactly the data we needed.

The ESO 3.6-meter telescope in Chile spends much of its time observing Sun-like stars to search for planets using its extremely precise spectrograph, HARPS.

From these exquisite spectra, we have shown that α was the same in the 17 solar twins to an astonishing precision: just 50 parts per billion. That’s like comparing your height to the circumference of Earth. It’s the most precise astronomical test of α ever performed.

Unfortunately, our new measurements didn’t break our favorite theory. But the stars we’ve studied are all relatively nearby, only up to 160 light years away.

What’s next?

We’ve recently identified new solar twins much further away, about half way to the centre of our Milky Way galaxy.

In this region, there should be a much higher concentration of dark matter – an elusive substance astronomers believe lurks throughout the galaxy and beyond. Like α, we know precious little about dark matter, and some theoretical physicists suggest the inner parts of our galaxy might be just the dark corner we should search for connections between these two “damn mysteries of physics”.

If we can observe these much more distant suns with the largest optical telescopes, maybe we’ll find the keys to the universe.

Michael Murphy, Professor of Astrophysics, Swinburne University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.