Orientation: the politics of the sacred

The word “pagan” is one of those words that has been worked over by monotheists and secular rulers so that it has many meanings, mostly negative. This has been the case except for the past fifty years when Neopaganism has made a comeback, thanks mostly to the women’s movement. In his book Being Pagan, Rhyd Wildermuth writes that:

Being pagan means being of the land, rural villager, rustic. In modern terms, being a peasant or being a country bumpkin as opposed to the city (39) …

Rhyd tells us that Frankish or German people were called “heathens” by missionaries, meaning “dweller of the hearth”. Heathen lands were the most uncultivated places not suited for large-scale farming such as moors, scrubland and sparse forests. This land is better for small grazing animals like sheep and goats or for hunting small game. Because of the lack of large scale land productivity, politically it tended to remain independent of urban control far longer than other agricultural people who became dependent on cities.Heathens also more easily resisted Christianization and were made fun of by Christian and urban people because of this resistance.

In addition, my own stereotypical picture of pagans is that we are:

- Materialistic

- Overly sensual

- Have sacred presences that are carnal and undignified

- Violent

- Racist (heathens or Nazi’s)

- Uncivilized

Rhyd writes that when people ask him what being Pagan means he points to the flooding, the droughts, the melting icecaps, the extinctions and the plagues in the world today. He writes that in pagan animist societies people took care of the land because being an animist means everything is alive and nothing is inanimate. If we lived as animists, terrible ecological circumstances would never have been possible.

When the Christians strove to take over Celtic lands, they created stories by which old pagan presences were conquered, driven out or demonized by magical or miraculous means. The stories of Graoully, Coulobre and La Tarasque are examples and these stories were widespread in France, Spain and Germany.

Scope of this article

Rhyd Wildermuth in his book Being Pagan outlines a high contrast between our alienated existence in monotheist, industrial capitalist society while taking us back in time to when we are not alienated, in pagan animistic societies. He does not specify what kind of societies these are. My best guess is he was mostly talking about hunter-gatherers, various kinds of horticulturalists and simple, small-scale farming societies. He contrasts differences in how time and place was conceived. He shows us how the treatment of the land, including fruits, vegetable, trees, plants and animals was radically different in animistic societies

One of his most interesting contrasts was how the body and mind were thought to be related. He points out that in industrial capitalist societies the mind drives the body. In animistic societies bodies drove minds. More on this later. In current times, those who are monotheists believe they have a soul that transcends death. What did pagans prior to monotheism think about this? For them, connection to the ancestors was part of the same ecological networks that connects us to rocks, rivers, plants and animals. Today, at least in Yankeedom, ancestors don’t matter. What happened and why did it happen?

Rhyd says that pagans do not believe in the supernatural. But if pagans populate the sacred worlds with gods, goddesses, earth spirits and ghosts how can they not be supernatural?

Years ago Benjamin Lee Whorf argued that language is an organ of perception. If animists think that everything is alive, how does this translate into language? We will see how it affects the proportion of nouns and verbs used, along with the proportion of tenses to indicate the past, present and future.

Because we live in a global age, all sacred traditions have to face the problem of mixing. Monotheism has been impacted by globalization, but Christian monotheism in Europe has a clear developmental trajectory: Catholicism and Protestantism. For pagans the problem is deeper because Neopaganism has had about 150 years of eclecticism. Its history has been broken up, gone underground and resumed. Should Neopagans mix with native traditions in the United States or in African societies? Should Neopagans incorporate Shintoism? Some say this is “cultural appropriation” while others say mixing traditions has always been part of polytheism.

For most of this article I will be analyzing the book Being Pagan. However, I will also be adding my own material to fill out his argument, and hopefully make it better.

Process “becoming” philosophy vs being “static” philosophy

When verbs become nouns

Rhyd points out that every known language has two primary kinds of words: nouns and verbs. They also have two secondary categories, modifiers, which are adjectives and adverbs.

- A noun is the name of something specific

- Verbs describe actions

- Adjectives describe a noun

- Adverbs describe an action

He points out that languages spoken by indigenous peoples and by ancient cultures use more verbs than nouns – especially animist cultures. Modern languages like English and French, both products of monotheism, employ more nouns than verbs. In addition, every language has a certain proportion of words devoted to describing tenses: the past, present and future.

For industrial capitalist societies, once the present is over it becomes past, and pasts are connected to things like documents, statues, relics. For animist cultures, everything is alive and moving. The present tense is part of a never-ending act of becoming. For Western monotheists today, there are people who personally are lost in the past or the future. The inability to concentrate on the present is so bad that people take meditation classes to force them to live in the present. Animist cultures have no problem living in the present.

Furthermore, it is no accident that industrial capitalist societies are more “thing”-oriented because they have writing. Writing freezes thoughts into words and words become objects. In oral animistic cultures what people say is more in the service of social-psychological interaction. On the other hand, thoughts have a short shelf life when the conversation is over. With the introduction of writing, language becomes more static and words become things frozen on a page.

Time of the moon

We are all familiar with the calendar and tracking our time in relation to days of the week? But how far back does this go? For most of the history of social evolution it was the light of the moon and its rhythm of the new moon, half-moon and full moon which set the course, the patterns and meaning of everyday life. For pagans, the moon isn’t only visible at night, but with careful training we can see it is also visible during the day. Activities were tracked according to changes on and during moons cycles over the course of a month. Rhyd points out that the origin of the word month comes from the moon. In terms of tracking human time, at the beginning there was the month, long before there were days of the week.

There is nothing spiritual or supernatural about the moon. The tides come and go twice a day, pulled by the gravity of the moon. The tides sweep in and out daily n rhythmic patterns, twice out twice in, pulled by the moon’s gravity. The moon has different phases. During the full moon or the new moon the tide sweeps further inland and returns further from the shore than at other times. Knowing the phases of the moon is a very practical affair. It tells us when we are more likely to find fish that might be scattered on the shore. All an animist would have to do is look at the moon’s face to know when food might be more plentiful and what the conditions were best for a boat entering the ocean.

Research shows that many animals are more active during the night of the full moon. People sleep later during the full moon and longer during the new moon. Before the invention of electric lighting which enabled humanity to have the night permanently lit, people who hunted did so by using the light of the moon. Early pagans knew which phase the moon was in and they acted accordingly.

Rhyd describes how this impacts him personally:

I always feel my absolute lowest when the new moon is new and just before it is new… Noting how certain things are easiest to complete as the moon wanes, because I know that I am often more tired and feel less intuitive during new moon, I try to avoid scheduling too much for that time and instead try to rest. I find my life much more grounded and anxiety is rarely something that can overwhelm me. (22-23)

Knowledge of the moon only appears as superstitious to people living in industrial capitalist countries because they are those who are blinded by city lights, and the lack of need to hunt and fish for food. They have stopped paying attention to the moon. Until the mechanistic phase of clocks, we scheduled activities looking at the moon as well as the time we go to sleep. We city Neopagans are encouraged to look at the moon, find out where it is and what phase it is in, as well as where it has arisen and where it has set. Like anything else, it takes practice for our eyes to become sensitized to the moon and its movements. In modern city-life these sensitivities are deadened. For us, each night seems like the next and we go to sleep at the same time regardless of the moon or whether it is wintertime or summertime. We have lost our rhythm.

Cyclic time to clock and linear time

It is not just the moon that waxes and wanes. The yearly seasons change throughout the years depending on the zones around the earth. Plants and animals follow the seasons, going through developmental cycles of growth and death. Different animist cultures follow suit, dividing their cycle of the year according to the temperate or polar regions. Those who have four seasons in temperate zones divide their years into four quarters. The “time of land” tells us when berries or tomatoes are ripest. On the other hand, upper-middle class people living in industrial capitalist societies, especially Yankeedom, have come to expect the same fruits and vegetables to be available all year, regardless of the season.

Rhyd says the land has character just like human temperaments do. She is gruff, grizzled, hearty, stoic, or lush. The combination of minerals are different in some places than they are elsewhere. She is shaped by the rocks, the wind, the cold, heat and the humidity. Rhyd points out local lands themselves have a unique taste. Whether wild or domesticated, those same plants and animals taste differently depending on the quality of land they are grown and live in. By saying pagans are of the land it just means understanding basic ecological dynamics: how it works on humanity and how humanity works on it.

This natural time was the enemy of Protestants anxious to abolish the seasonal holidays, and capitalists who wanted to discipline workers to punch a time clock and work long hours regardless of the seasons or the phases of the moon. They wanted disciplined workers to accept clock time. In animist time, when people worked, they also slept during the day. Even as late as in early modern Europe, when artisans were given an order by merchants, they took breaks when they wanted to. They controlled the pace of their work. In the early Industrial Age capitalists were insensitive to workers being sick or tired. If they didn’t continue working they would be replaced.

Keeping time has a long history deep into ancient civilizations. They used the sun dials, water clocks and hour-glasses. But these were not precise and they were not used by artisans or peasants. Clocks were used by the upper classes as a luxury item. They were used by alchemists in cooking the elements or by astrologers for casting the horoscope of great political figures. Bell towers were used to remind people to pray or to announce foreign invasions or fires.

In addition, as cities rose and farming declined the drive to see time cyclically waned. Cyclic time was replaced by linear time. Capitalists hate the past because the past is a reminder that their system is historical. Linear time is laid out like a straight line moving from past to present to future. Once the past is over, unlike cyclic time, it never returns. But capitalists need to display the future as always open, and where anything can happen. This feeds into the ideology that any person can become a capitalist if they have the right psychological state.

Becoming Body

One of the most interesting arguments in this book is the relationship between the body and the mind. Rhyd says we do not have bodies, we are becoming bodies. This means that:

- There is no getting out of being a body

- We are becoming bodies. This connects to the difference between process and static philosophy that we touched on earlier.

For example, Rhyd points out that hunger and thirst were not something you were or had, but something you did. Being thirsty is passive state, a condition that needs to be resolved. It is something that has happened to you. On the other hand, thirsting for water is an active state. It is not happening to you. It is something you try to do something about. But then you expend energy at work and you become thirsty again. The body is constantly reproducing itself with needs, satisfaction and new needs.

How we came to have bodies

Just as we have externalized and reified our language, we have externalized our bodies and separated them from ourselves, making them something we have rather than something we are. This negative attitude about the body is not unique to Western monotheism. In the East we hear we are “trapped in the body” or we are “a prison of flesh” that needs to be escaped from. Occultists claim we “are inhabiting different bodies”. Teenage girls “hate their bodies”. To say we have a body implies that there can be a state without one. What’s left? Minds without bodies, a product of patriarchal sacred traditions, not paganism.

According to Wildermuth, the reasons for this anti-body orientation include the development of Christianity with the separation of the soul from the body. Secondly, Descartes added to this by claiming the mind can be separated from the body. Lastly, capitalism insisted on the discipline of the body during capitalist production to conform to the pump and lever in Early Modern Europe. Later, human bodies are disciplined again as a reflection of the complex machines and the steam engine in the second half of the 19th century. In the early 20th century the bodies of workers were subjected to the time and motion studies of Taylorism.

Ecological networks are bodies

In pagan understanding, everything that exists is in terms of living bodies. Ecological settings are bodies too. Having a body is like seeing a body mechanically, seeing a body as a collection of separate things. Imagining having bodies has negative ecological consequences. Seeing the forest as a collection of separate beings rather than a body leads to:

- Killing off of species of insects

- Hunting too many of the birds and animals

- Felling too many trees

- Damming a river or taking too many fish from a lake which can turn the entire system into something unlivable for everything there

Doing this to our ecology is like removing an organ from a human body and expecting it to work right. It is only possible for us to do such destructive things to the natural world because we do not see it as body, but rather separate things unrelated to each other. Rhyd tells us that:

Over the last 100 years alone, 543 species of terrestrial vertebrates (reptiles, birds and mammals) have gone extinct worldwide, a rate of disappearance that would have historically occurred over 10,000 years. That is, the rate of extinction is occurring 1,000 times faster for such beings now. (91-92)

Alienation from trees

Rhyd points out that oaks are special trees for pagan people. Oaks are more likely than shorter species of trees to be hit by lightning and are more likely to survive a lightning strike. It is no accident that oaks were associated with the gods of thunder. Oaks also protected other trees from storms and high winds. Many oaks grow very old, outlasting the rise and fall of civilizations. When oaks die they are put to sacred use as shrines or temples by Celtic and Germanic peoples An oak struck by lightning became a political ritual site, often becoming a place for major decisions. The importance of oaks to pagans was not lost on monotheists who ordered the cutting down of oaks dedicated to Thor to make the conversion of pagan peoples to Christianity easier. The Christians then built Cathedrals from the oaks.

Alienation from other animals

In my diet, much of my protein comes from eating chicken and fish. I know two women vegans who insisted I watch documentaries of what goes on in slaughter houses and chicken factories. I watched part of one and then turned it off. I didn’t want to know my eating habits were linked to so much suffering, but I continue to buy chicken at the supermarket. I’m confident I am not alone. We buy meat in packages at the supermarket but we rarely know anything about the process by which these dead animals arrived there. Rhyd points out that the flesh of these beings:

is processed by machines into forms that would be unrecognizable to people even a hundred years ago. Cows, pigs, chickens live in settings that look much more like factories than the pastoral landscapes. (93)

Contrary to all this, animist views see all living forms to include not just plants and animals, but rocks and rivers are also connected to the ancestors. Animists are engaged in reciprocal exchange of gratitude. When humans killed an animal, they apologized to the animal and made sure that future hunts were conducted in ways that did not thin out the species they hunted. This contrasts to monotheists who tell humanity we have “domain over nature. It is there for us to do what we want”. It is easy to see how this domain would directly link up to the scientific exploration of the 17th and 18th centuries and capitalist exploitation of land through colonialism in the 19th and 20th centuries.

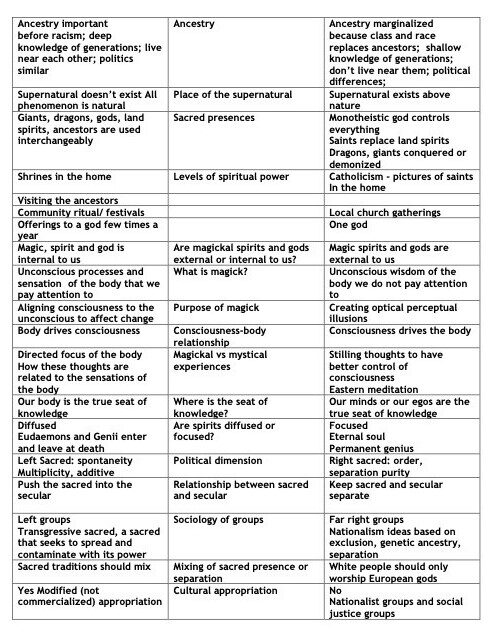

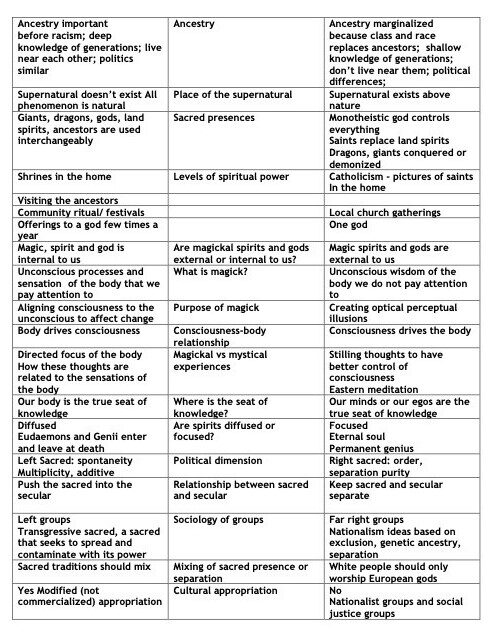

The importance of ancestry for pagans

Today, especially in the United States, ancestry is not anything that is taken seriously. For the most part, people can’t trace their genealogy beyond their grandparents. Sure, there is new interest in tracing genealogical trees but in my opinion this is a fad. Whatever value and meaning this has, it is certainly not pursued with the same level of building a serious sacred connection. Most Yankees do not hope to have their ancestors come to them in their dreams, in their homes or giving them direction. Our relationship with ancestors is thin. In part, this is because we didn’t live near them because capitalist enclosures drive communities apart. This has been widened even further in the 20th century by capitalists. Geographical industrial specialization drives people to work in different parts of the country. In addition, the rate of change in industrial capitalist societies is so fast that the wisdom of the ancestors dries up quickly because the world has changed so much between generations. As gaps between generations grow, political differences emerge as to how to handle the change. Ancestry is marginalized as race and class identities replace them.

Pagans on the other hand, because they were not displaced, lived in the same location for many generations and they could trace their ancestors well beyond their grandparents. Secondly, because the rate of change was slow, the knowledge of the ancestors was respected knowledge that did not change much between generations. This means their politics are similar. Lastly, since tribal societies did not have classes and groups, ethnic composition was similar. There was no class or race identity to compete with ancestry. In many cultures a common truth is that the dead speak to us in our sleep.

Scale of pagan presences

According to Rhyd Wildermuth, in most pagan societies there are four levels of scale.

At the bottom and the smallest level there are shrines to the home. On a larger scale there are rituals to the ancestors. On the third level there are community festivals which include arts and crafts. Lastly, there are offerings to a god a few times a year. It’s important to understand that these scales are not hierarchically organized. In other words, the gods do not control the community rituals, ancestors or shrine presences. What is true is that they are organized in terms of the frequency with which they are enacted, beginning with the shrines in the home. In animistic societies when something is strange or has gone wrong, the spirits are not seen as evil but in the wrong place. The job of the shaman is to understand the problem and resolve it.

What happens when monotheism arises? Shrines are marginalized and in the case of Catholicism, replaced by pictures of saints in the house. Ancestors lose their connection to the rocks, rivers, plants and animals along with their wisdom. Community rituals and outdoor places are replaced with patron saints. The pagan gods, whether dragons or giants, are demonized and replaced by a single monotheistic deity.

Are spirits, ancestors and gods internal to us or external?

The key to understanding the difference between animalism and monotheism centers on where the sacred source originates. For animistic people, consciousness is diffused so that spirits, ancestors and even gods are inside our psyche and project outward. This is based on the unconscious intelligence of the body. Under monotheism, our alienation from the body is an important obstacle to our understanding of magic. As a result, for monotheists both spirits and God are external, objective and have little to do with our psychology

Magic is the unconscious intelligence of the body

Rhyd has a very interesting although strange definition of magick. He argues that magick is the unconscious perceptual wisdom of the body that is constantly reacting to the real world, which we have forgotten to notice in our modern world. Our bodies are constantly steering us in everyday life. When we speak of the unconscious, partly what we really mean is everything that our body knows and senses.

A very simple example is body memory. It is a process by which you find your way through a dark room that you know very well. Another example is being able to drive down a familiar road where your motor skills take you home while you are zoning out on music. Another example is if you are playing the outfield and you know how far back to go for a fly ball just by hearing the sound of the bat. In the case of baseball, that body knowledge has never been consciously processed. We know things we don’t realize we know. A pagan definition of magick is aligning consciousness to the body in order to enact change. Consciousness is the servant of the body. It is the directed focus of the body. Magick means giving attention to what the body is telling us and acting consciously in accordance with it. Our conscious attention, including our minds or our egos, is not the true seat of knowledge.

Meditation is not magick. Rhyd says:

In most forms of meditation a person stills their thoughts in order to have better control over consciousnessand the ways in which it was directed. (158)

Magick is not about quieting our thoughts in a disembodied way. It is about listening to how those thoughts are related to the sensations of our body.

Eudaemons and genii’s vs the eternal soul and permanent genius

In animistic societies people recognized that benevolent protective presences entered into the person at birth and left the body at death. Even as late as the time of the Greeks such presences were called eudaemons. The Romans called them genii’s and made shrines for them. This was too much commotion for monotheists, and St. Augustine replaced these fluid presences with a noun like eternal soul. Long after monotheism, in 20th century intelligence testing, we have the same noun – like genius – which is permanently attached to the eternal soul. For pagans, people were not geniuses themselves but had a particularly helpful genii to whom they listened.

Left and Right Sacred

In the early days of animism, from hunter-gatherers 100,000 years ago up to the Bronze Age civilization of 5,000 years ago, animists kept to their local identity and did not try to mix cultures. The great civilizations of the ancient world certainly traded enough so that pagan people became aware of other pagan people. Did they keep separate or did they mix? Their answer was always to mix and to synthesize. With the rise of globalization, the knowledge across cultures became even more intense. However, in the last 50 years, Neopaganism arose as part of the women’s movement. Because Neopaganism has a broken and suppressed history rather than a single stream leading all the way back as monotheists do, it has to determine what it will mix and match with. A new problem emerged for Neopaganism as the New Age emerged in England and the United States. A significant number of New Age organizations were small capitalists who have overridden Neopagan resistance to commercialization. New Age organizers have offered people courses that have drawn from native cultures (from the United States and Africa) and have turned a nice profit. Some native cultures have fought back against this. So pagan mixing cross-culturally has become politicized because of the ravenous nature of capitalists for profits.

There are two tendencies within paganism. Right-wing pagans think that the sacred should be orderly, that there should be separation between the sacred and the secular and the sacred traditions should be kept pure, based on exclusion and supposed genetic ancestry. These are represented by far-right groups who are nationalist, some neo-Nazis. They say white people should only involve themselves with European gods.

The left-wing pagans care less about order and are more interested in continuing the historical paganistic mixing. The socialist wing is very aware of the exploitation of cultural appropriation but they don’t want to throw the baby out with the bath water. They want to trust spontaneously mixing, multiplying and adding. They do not want to keep the sacred and secular separate, but are committed to expanding the sacred into the secular. We do this, not because we want an animistic theocracy, but because sacred pagan life will challenge the capitalistic control over secular life.

What is ironic is the so-called social justice movements that demand that cultures don’t mix because they think mixing is inherently exploitative. Yet they wind up on the same side as the right-wing sacred pagans. They also want to keep things pure but for different reasons than right-wing pagans.

Criticisms

I do not disagree with anything that was said in Being Pagan. However, the contrast between rural tribal paganism and monotheism and capitalism is too severe and some transitions need to be at least suggested. For example, there is nothing said about the city paganism of the Greeks and Romans, the Alexandrians of North Africa or the city magick of Renaissance Italy. At least a few pages of some of the differences between city and rural paganism would have been very helpful along with some references. This is especially important since today the overwhelming number of Neopagans live in cities.

As I said earlier, the kind of animism described is overwhelmingly tribal. But in between tribal societies and industrial societies are agricultural states where the goddesses and gods predominate. Had this been included, there would be an evolutionary sense of movement from animism to industrial capitalism. As it stands now, Rhyd’s description of alienation would have come about gradually. Without that alienation seems to come out of nowhere. A few pages about the polytheism of agricultural states would have thickened history and minimized abrupt changes.

Third, it was disappointing to me to have the word “god” introduced along with land spirits and ancestors and used interchangeably. Typically, the word “god” is used to indicate a degree of power that is more powerful than ancestors or land spirits or nature nymphs, yet this distinction is left out. A good example is the Greek and Roman gods and goddesses who were superior to humanity in scope and scale. Why introduce the word god at all unless it was used to refer to something different than other sacred presences?

Fourth, In his book All That is Sacred is Profaned, Rhyd claims to be a Marxist. His purpose is to introduce Marxism to Pagans. But in Being Pagan there is no mention of Marxism. Given that Marxism denies the ontological existence of a spiritual world, it would have been helpful to explain somewhere, either in the preface or an epilogue, how he squares a Marxist denial of the sacred world with the paganism he espouses in Being Pagan, especially in his chapter “The Fire of Meaning”.

Fifth, the definition of magick is limited to tapping into the unconscious wisdom of the body. This is an important addition to pagan practice. But why call it magick? Why not call it “body” knowledge? Furthermore, magick is often defined as changing consciousness through the use of imagination along with saturating the senses though the use of theatre and the art as in “Tree of Life” magick. There is no mention of any of this.

Lastly, ritual descriptions are disappointingly skimpy and it makes it seem as if all pagan rituals are private. This ignores the fact that most pagans practice magick in groups. There should be at least some description of group rituals to see how his animism would be practiced.

• First published at Socialist Planning Beyond CapitalismFacebook

• First published at Socialist Planning Beyond CapitalismFacebook

Bruce Lerro has taught for 25 years as an adjunct college professor of psychology at Golden Gate University, Dominican University and Diablo Valley College in the San Francisco Bay Area. He has applied a Vygotskian socio-historical perspective to his three books found on Amazon.

Read other articles by Bruce, or

visit Bruce's website.