'Forgotten' American Sarah Krivanek Tells Her Story as She and Brittney Griner Are Freed from Russian Prison

Shortly before boarding a plane to leave Russia, American citizen Sarah Krivanek gets on a video call to unpack her harrowing year as a foreign detainee.

There in her deportation cell, she explains the "Sodom and Gomorrah" living conditions in a Russian penal colony — she's finally in an environment where she feels comfortable being candid, under the condition that her story remains unpublished until she's officially off Russian soil.

Living in a remote labor camp "was the equivalent of going to hell with the devil himself," Krivanek says. Being transferred to a temporary holding cell after completing her prison sentence last month shouldn't have felt like freedom, but it did — barred windows and all.

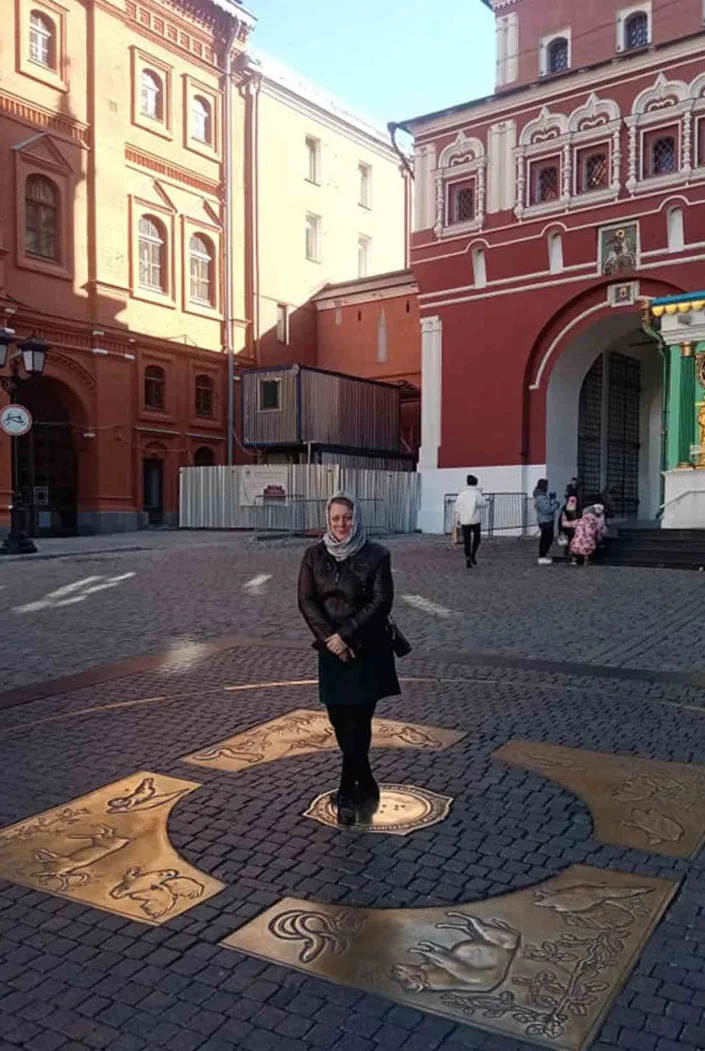

Sarah Krivanek In the Russian deportation cell where Krivanek spoke with PEOPLE

"Even though I'm like a bird in a cage and I can't get out I feel somehow protected here," she says. "I feel safe." Not to mention she's warm, a sensation she'd forgotten while exposed to brutal Russian weather in the colony, and knows that on Thursday she will be on her way home.

Krivanek finds it draining to recall the brutal regime in the colony and says she will likely "seek help and support" upon her return home. She speaks calmly, occasionally struggling to recall her English and frequently lapsing into Russian. But in the end, PEOPLE hears for the first time what really happened after the well-respected accountant from Fresno, California, ventured to Russia for a fresh start.

Sarah Krivanek Facebook

A Rough Entry into Russian Life

Krivanek, who has four adult children and three grandchildren, first moved to Moscow in 2017 to be with a Russian man she'd met on a Russian culture Facebook page. The relationship turned sour, but she decided to stay and continue her "meaningful work" teaching English to schoolchildren.

Some years later she formed another relationship with a neighbor, Mikhail "Misha" Karavaev. (Even then, she insists, the true love of her life was her Maine Coon cat Drago whom she had brought with her from the U.S. "He was my heart and soul," she says. "I'm having to leave him behind which breaks my heart, but I hope one day to come back for him.")

In August 2021, while Krivanek was working at a prestigious school in Moscow, she slipped on ice at the playground and broke her wrist. She was fired and, with no income, was forced to move out of her apartment into Karavaev's rented room in a communal apartment in the Odinstovo region of Moscow. The day she moved in, her father, who had been helping her financially, died.

"Then one night, Misha had been drinking with neighbors and he started to beat me up. I tried to call the police, but they hung up on me. The next morning, I look in the mirror and I'm covered in bruises and my hand's broken," she says.

Sarah Krivanek Facebook

"A couple of days later he started in on me again — and he's two meters tall — so I grabbed a knife in defense and nicked his nose with it," she explains. "He saw the blood and freaked out."

This time, when their communal apartment neighbors called the police, two officers turned up and took them both to the station. Krivanek was booked in jail on two charges: intent to kill and causing slight bodily harm. Karavaev was allowed to go home.

"The next day Misha had sobered up and he came in and told them it was all his fault because he was drunk, and he'd hit me first and that I was just trying to defend myself and had never threatened to kill him," she says.

After he withdrew all the charges in a signed affidavit, Krivanek was released but told not to leave Moscow until they closed the case.

"They promised I wouldn't even 'see' a courtroom," she says. "They lied."

A Desperate Attempt to Flee

Following her release in November 2021, Krivanek had no other recourse but to move back in with Karavaev, where she claims the beatings continued. Her family and friends in America persuaded her to go to the U.S. Embassy in Moscow to ask them for help getting home. She insists that she had no qualms about leaving the country, because a month before the police investigator allegedly told her the case would be closed "in a couple of weeks."

"I believed I was free to go, so I contacted the vice-consul Luke Davis by email to say I was in an abusive situation which had ended up with me in a police cell, and had no money. He told me to come on in on a few days later with my suitcase."

Krivanek went to the embassy and filled out all the documentation for a government loan for her flight. She was taken to the airport in a taxi with the vice-consul who dropped her off at the airport hotel. "I wasn't nervous at all. I figured I could go home, get another Russian visa as mine had expired and then come back for Drago who was with a friend. The embassy wouldn't let me take him."

RELATED: Sarah Krivanek Was 'Desperate' to Leave Russia Before She Was Arrested, Says Family Member

The next morning, she checked in her luggage, picked up her boarding passes and walked to passport control, chatting happily to her friend, Anita Martinez. "I had no thought I was in danger," she says.

The passport control officer took her passport away and returned with a superior officer who grabbed the phone from her hand mid-conversation.

"I was yelling, saying, 'What are you doing? Give it back!' but he turned it off and told me to sit down because the police were coming to pick me up. I still didn't understand what was happening." Martinez has previously corroborated this part of the story, saying it was the last time she heard from Krivanek.

'A Lamb Led to the Slaughter'

Krivanek was escorted back to Odinstovo in a police car and placed in a detention cell to await a court hearing. "It was a really small concrete room with no light and one tiny window in the roof with a hole in the ground for a toilet. There were four of us in there. I was petrified."

She asked her lawyer to call the embassy and update them on her arrest so that they would visit her, but nobody came. She says there were also no embassy personnel present at her hearing nine days later, nor at her trial. It's February of 2022 now.

"I didn't understand the legal jargon and I was having an anxiety attack and didn't want to cry," she says of her trial. "I felt as if I was left alone and abandoned." She refused to speak without an interpreter — when one was provided, Krivanek managed to slip her a crumpled note begging her to call the embassy and ask them to contact her family.

Karavaev was called as a witness in the trial and again withdrew his accusations, insisting he was the perpetrator, not Krivanek. When she was sentenced to one year and three months in a penal colony anyway, she was numb with shock: "That whole time I was under the impression they were going to release me and close the case. I couldn't speak a single word, I was sobbing, mumbling words that made no sense."

Krivanek's lawyer, Svetlana Gorbacheva, immediately appealed the verdict, and she was sent back to the holding cell to await a decision. There, she got wind that another American — who we now know to be WNBA player Brittney Griner — was going through something similar.

"I heard from the other girls there was another American woman being held in a nearby detention cell awaiting trial," she recalls, "but I didn't know that was Brittney Griner and our paths never crossed." The two would go down parallel paths — unjust sentences, failed appeals and labor camp sentences — over the next several months, even getting released back to the States on the same day: Thursday, Dec. 8.

When Krivanek's appeal was denied, she says, "Even my lawyer cried. I'm grateful that even though I didn't have the embassy, I had her.

Krivanek now believes that in Russia "there is no fair trial. Even with the most expensive lawyers you're guilty anyway," she says. "I was a lamb led to to the slaughter. Three people in cells next to me hung themselves while I was there. This is very sad."

Gorbacheva confirms to PEOPLE that the harsh court decisions came as a shock. "It was not an imprisonable offense — it was an extremely unjust and cruel sentence," she says. "I feel so sorry for her on a human level."

Banished to 'Sodom and Gomorrah'

"We're taken to the KP-4 colony on May 22 in the back of a police van handcuffed to the metal doorway with no windows. When we're led in, I'm terrified. All I have is a sliver of hope that somebody will find me."

Walking through the prison gates she now realizes "was the equivalent of going to hell with the devil himself."

But she learned to live with the punishing work regime in the sewing "slave" factory, and the food that was little more than slop, causing severe malnutrition. She even adjusted to the freezing temperatures in winter with no heating in the factory, and the suffocating heat in summer with no ventilation.

It was the psychological torment imposed by other inmates — and encouraged by the prison staff — that made it "what the girls called a Hell Camp."

Ryazan Novaya Gazeta The penal colony where Sarah Krivanek was held

The colony housed both male and female inmates in separate sections, and Krivanek says that the men were used to rape women inmates as punishment. "Sex trafficking happened there, prostitution happened, rapes too. As a punishment for something they were personally offended by, they arrange for you to be raped by other inmates, male or female in the bath house. It's planned. They lock you in with them and guard the door."

"It's like Sodom and Gomorrah in the camp. What is sinful to a normal person in the outside world is the opposite for them. I was stupefied when I first got there. I couldn't wrap my mind around what was happening. They just want to humiliate and crush you," she says.

She adds "the administration didn't touch me. They used the inmates."

Krivanek has a strong Catholic faith and says she will not be able to describe one particular punishment until she has talked to a priest upon her return to the U.S. The punishment was so traumatizing that Krivanek fasted for the following three weeks and covered her head with a cloth.

The incident occurred after Russian human rights activists asked for a federal penal colony inspector to visit her. She told him that she had not been permitted to make a call to the embassy or her lawyer and also told him of the "unthinkable, mortifying punishments" she had been subjected to.

Following the interview, which was attended by a prison guard, she was then punished for telling tales by a female inmate dubbed Darth Vader.

"She was the evil queen of the camp with her court of cronies. I was naïve to complain. I've never seen such abuse. How could those things come out of someone's mind?" Krivanek adds, "Everyone is scared of her. Her job was to humiliate and destroy you. She ruled us with fear and abuse. She built a prison inside of a prison."

Worse, she claims, the woman was allowed to do it. "The administration used her to punish, control and discipline her subjects."

Worked to the Bone

Krivanek lived in a barracks of 40 women in a cell with eight other inmates in single bunks. She survived on virtually nothing but cabbage and bread. When she wasn't working in the factory from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. (she earned less than a dollar for her first month's work), she was on cleaning duty.

"Our tasks were assigned by Darth Vader, who hated me, so my job was to scrub the toilets every day, scrubbing everyone else's s---, so I had my head down a toilet the whole time and it's bad on the kidneys if you constantly have your hands and feet in cold water." There was no hot running water in the cells.

Krivanek says her health deteriorated, telling PEOPLE that she's suffered severe back pain from scoliosis and a fused spine after getting in a serious car accident, and also suffers from a chronic kidney stone condition. "When it comes to medical care, forget it. All you get is a mild painkiller tablet."

Prisoner Monitoring Service Sarah Krivanek in a meeting room at the Russian penal colony

Punishment from the administration was being put in the isolation cell for up to two weeks. It's a small box with no mattress, and you're not allowed to sit or lie down in the daytime. Krivanek managed to avoid the isolation cell by staying "meek" and always fulfilling her work quota.

"In summer we worked outside weeding with our hands. You get cuts and sores and you're bleeding." Krivanek was concerned, she claims, because many of the inmates "were HIV positive or had full blown AIDS. If they didn't have money to buy medication, they died."

"What you do as protection there, is don't show any emotions. Don't cry over the family who seem to have forgotten you because that gives them ammunition that you're all alone and defenseless," she explains. "So, I cried over Drago my cat. I let them think 'this is one crazy lady' and leave me alone."

She had befriended the stray cats and kittens in the grounds of the prison, but before a routine prison inspection, she claims they were all rounded up, put in bags and thrown onto a bonfire. "It was genuinely evil."

Cut Off from the Outside World

Most inmates have friends and family on the outside who send money to use in the prison shop to buy luxuries such as soap and fresh food, but Krivanek had nobody. She also had no money on her prison account to make phone calls within Russia.

"I had no contact with the outside world at all. No news, no TV, no nothing. There's a caste system in there and if you have no family or friends on the outside, then you're the lowest of the low," she says.

RELATED: Inside the Russian Penal Colony Where Brittney Griner Will Serve Her 9-Year Prison Sentence

She repeatedly filed requests with the administration to make a call to the U.S. Embassy in Moscow but was not permitted to do so. Eventually, on July 21, seven months after her abortive attempt to leave with the help of the vice-consul, a male inmate smuggled his unauthorized phone to her so she could make a secret call from sick bay. She was only able to speak long enough to tell them which prison she was in before the signal was lost.

Following her complaint to the prison's inspector, she was eventually permitted to make another call to the embassy in August through official channels. "The diplomat told me they'd heard my last call and knew where I was and promised that someone was coming. They also promised to contact my family." The embassy did not return PEOPLE's request for comment about Krivanek's reported exchange.

After the call she waited with bated breath but heard no more. With no contact from outside the camp her despair deepened: "I waited and waited but still no one came. I also felt my friends and family had abandoned me. I thought the embassy must have contacted them and didn't know that they hadn't. Or how hard it was to contact me from abroad."

She visited the little church in the prison grounds whenever she could to pray for wisdom and strength. "Being a Catholic I couldn't commit suicide, but when I went to be bed at night, I would pray to the Lord that he would take me."

She was not permitted to attend the Eucharist for a second time in the church as punishment for having kissed the cross during the first service. She hid the cross she wore under her clothes at all times for fear of persecution.

'They Found Me!'

Then came the turning point which she says "saved my life." It was when PEOPLE, which found out where she was staying through a relative, asked a contact in Russia to send her an email letter through the prison system. It said that her family and friends knew where she was and loved her.

She received it on Sept. 1. "I was in the factory when they brought it to me. I read it and ran out and round the corner and cried and cried with happiness. One of the girls followed me and said: 'What's wrong?' and I said, 'Oh my God, they found me! They found me!'"

"I was so overwhelmed because deep deep down in my heart where no one else could see except God himself was that small sliver of hope that they were looking for me and that they wouldn't give up," she says.

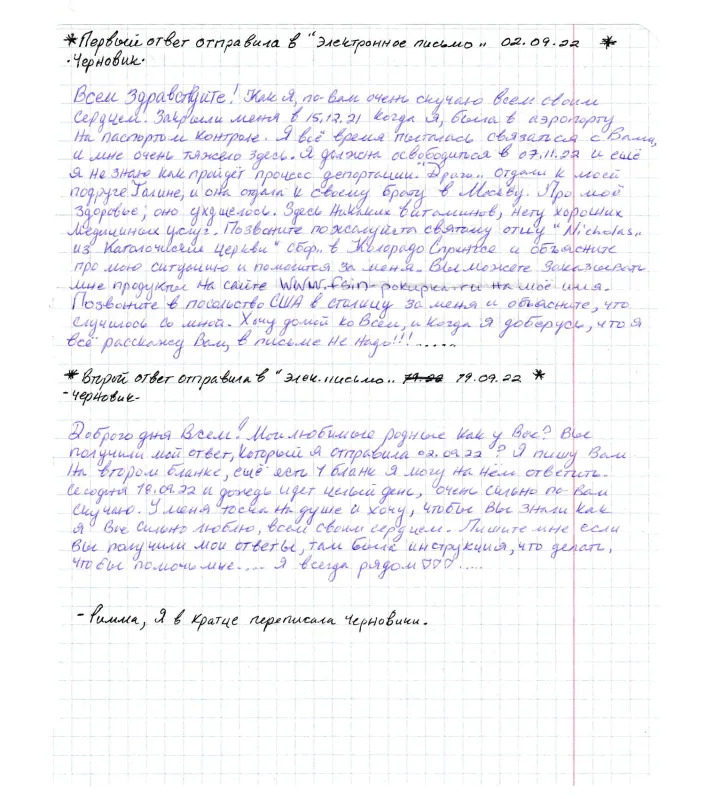

A letter from Sarah Krivanek, written in Russian

After that, everything changed for her. She wrote back and received more letters from human rights activist Natalia Filimonova, of Russia Behind Bars, whom PEOPLE had reached out to. Filimonova also arranged for packages of supplies to be sent to her, which were paid for by her friend Martinez.

"It was like being given a loaded gun. I had power," recalls Krivanek. "I was treated differently. Before that you are victimized for having no one who cares about you. Now I could stand up to them."

"Now Sarah has a posse," she explains. "Someone's got her back. They didn't succeed in destroying me."

Martinez was able to transfer money for more supplies and pay for money on her prison phone card so that she could keep in touch with Filimonova and loved ones until her release on Nov. 7.

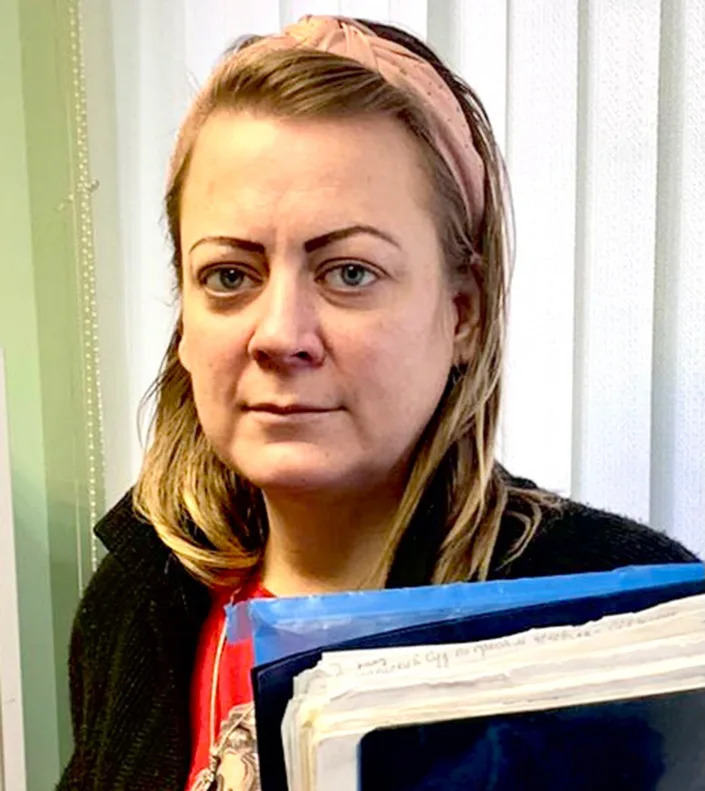

Sarah Krivanek

When she made it to the detention cell, Russian human rights activists were able to return her own cell phone from the police files in Moscow. Martinez was the first person she called.

"We had such a long conversation, for hours," says Martinez. "We laughed, we joked around. I mean Sarah's there. The same Sarah but she's a lot stronger that's for sure. I knew if anyone could get through this, it's her."

The U.S. Embassy arranged a repatriation loan to buy her flight home to California, which Krivanek will have to pay back with the help of a fundraiser organized by Martinez. Two officials also attended her deportation court case. She managed to talk briefly to them and asked about Davis, who had accompanied them to the airport. "They told me he'd been kicked out of the country," she says. (PEOPLE could not independently verify whether he had been expelled from Russia by the time of publishing.)

Krivanek remains bitter about the perceived lack of support from the embassy throughout her ordeal. "They abandoned me," she says shortly.

Asked what she misses most about America, she replies: "I only miss my family and my friends. That's all I know for now. I can't say I'm looking forward to anything else except being with them."