Digital technologies like drones are being heavily promoted to address the threats of climate change and biodiversity loss. (Unsplash)

THE CONVERSATION

Published: December 12, 2022

With biodiversity declining at unprecedented rates and less than a decade remaining to avert the worst effects of climate change, world leaders and policymakers are on the hunt for new and innovative solutions. In the halls and meeting rooms of global COP conferences, digital technologies have been heavily promoted to address these interrelated threats to our ecosystem.

At the recent COP27 climate conference in Egypt, the Forest Data Partnership — a global consortium co-ordinated by the World Resources Institute (WRI) in partnership with the U.S. Department of State, NASA, Google and Unilever — called for a “global alliance to unlock the value of land use data to protect and restore nature.” The WRI promoted its Land and Carbon Lab to measure carbon stocks associated with land use.

Nature4Climate — a coalition of 20 environmental organizations — revealed a new online platform to help implement natural climate solutions. They also exhibited a report on the “nature tech market.” At the COP15 biodiversity conference in Montréal, NatureMetrics, a provider of nature intelligence technology, launched a new digital dashboard to enable standardized measurements of the health of ecosystems.

Many, however, see such efforts as a dangerous push to get untried and untested corporate technologies accepted as “nature-positive solutions” in the Convention on Biological Diversity and climate negotiations.

As researchers examining the role of technologies in biodiversity monitoring and protected area management, we find that these digital technologies have the potential to yield positive results, if co-developed and used ethically with Indigenous Peoples.

Conservation and Big Tech

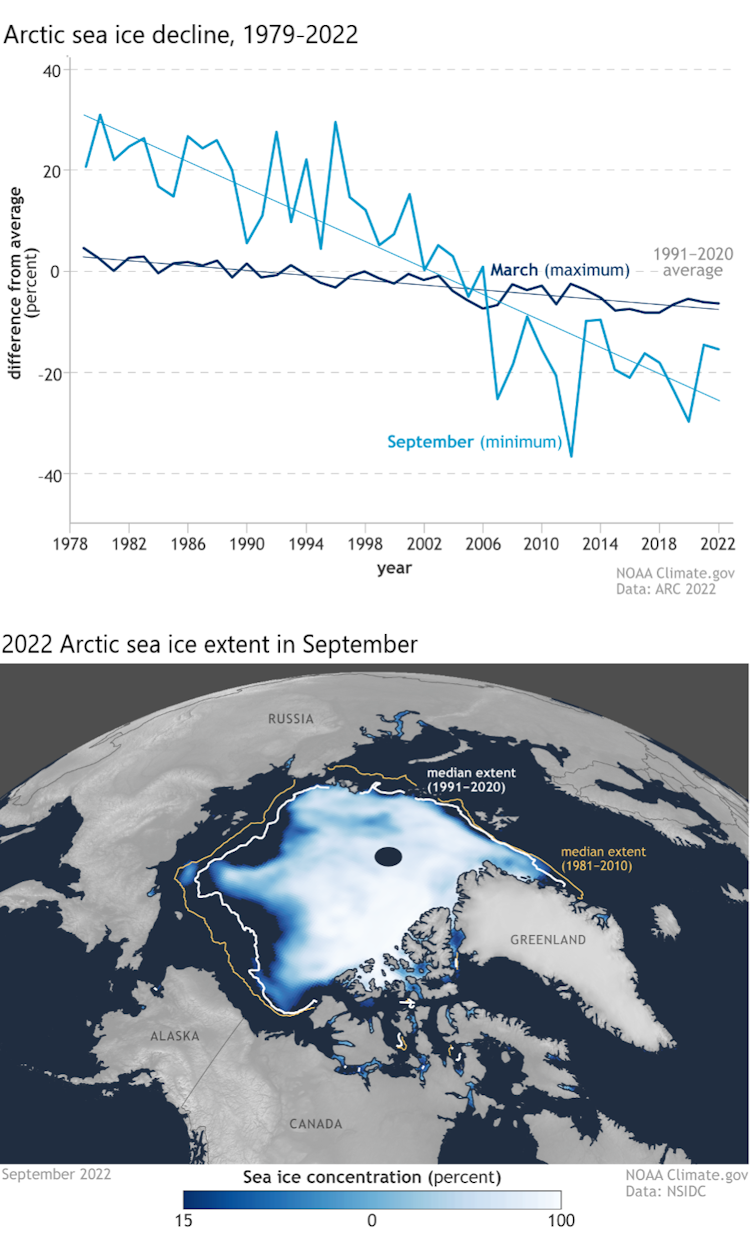

The influence of the tech industry in environmental governance has grown considerably over the past decade. Tech giants like Microsoft, IBM, Google and Amazon, as well as philanthropic counterparts like the Bezos Earth Fund, have invested significantly in technologies to address global environmental issues.Today, technologies are transforming the world’s forests and oceans into new frontiers of digital commoditization and investment. (One Earth/Wageningen University & Research), CC BY-NC-ND

Microsoft’s $50 million “AI for Earth” program, for instance, aims to “transform the way we monitor, model and ultimately manage Earth’s natural resources through grants, technology and access to data.” Such programs, including the Forest Data Partnership, have helped establish partnerships involving philanthropic, academic, non-governmental, public and private sector institutions.

They not only transform conservation, but natural environments as well. The deployment of digital technologies throughout natural environments, from satellites and aerial sensors to drones, camera traps and wearable sensors, has transformed the Internet of Things into an internet of trees, oceans and wildlife.

In our new economic context, in which data is the new oil, such technologies also transform the world’s forests and oceans into new frontiers of digital commoditization and investment.

Climate action or corporate greenwashing?

Critics warn, however, that these techno-centric solutions are simply corporate greenwashing and that they actually intensify biodiversity loss and climate change. While Microsoft, Amazon and Google tout the use of their technologies for environmental good, they continue to sell cloud computing and artificial intelligence services to oil companies around the world.

Research on Microsoft’s “AI For Earth” program shows that it greenwashes Microsoft’s corporate reputation, while its cloud computing and AI products are promoted to help oil companies better extract and distribute oil. Its vast data centres also use significant amounts of electricity, much of which comes from fossil fuels.

While Microsoft does attempt to offset its emissions by investing in California’s Klamath East project, a stretch of protected woodland managed by a forest products company, its carbon offsets have literally gone up in smoke in recent wildfires.

Similar claims have been made about Amazon and its environmental programs. While Amazon Web Services advertises its support for conservation and climate action, the company continues to drive greenhouse gas emissions by offering its cloud computing and AI services to the oil and gas sector.

In a critique of the Forest Data Partnership, the environmental organization Greenpeace argued that it is “nothing but a green light for eight more years of forest destruction, with little respect for the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.” It also argued that this allows polluters to do more business as usual through “carbon trickery instead of advancing true climate action.”

Technology for a just and sustainable future

At COP15 there has been a critical parallel movement to support Indigenous-led conservation to meet global biodiversity and climate change commitments.

Making up just five per cent of the global population, Indigenous Peoples steward 36 per cent of our remaining intact forests and 80 per cent of the world’s biodiversity.

Digital technologies, however, often marginalize local and Indigenous communities in conservation by supporting a shift toward more militarized and coercive approaches to conservation that position communities as targets of surveillance and policing.

Given these concerns, it is important to think critically about the role of digital technologies in global biodiversity and climate frameworks. Can these digital technologies truly support Indigenous-led conservation, climate action and reconciliation with the Earth?

The first step to this would include monitoring new technologies in the new biodiversity and climate frameworks. Digital tools must not be used to maintain the status quo by securing carbon credits and corporate profits. Instead, they need to be co-developed ethically and used with Indigenous Peoples and land defenders to protect their rights to — and control over — the environments they cultivate, care for and protect.

Authors

Postdoctoral Fellow, Dahdaleh Institute of Global Health Research and Faculty of Education, York University, Canada

James Stinson receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC). He is Principle Investigator of the SSHRC-funded project "Smart Conservation and the Production of Nature 3.0 in Belize."

PhD student Global Sociocultural Studies, Florida International University

Disclosure statement

Lee Mcloughlin receives funding from Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC). He is a research assistant for the SSHRC-funded project "Smart Conservation and the Production of Nature 3.0 in Belize".