1 of 7

VATICAN CITY (AP) — Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI is rightly credited with having been one of the 20th century’s most prolific Catholic theologians, a teacher-pope who preached the faith via volumes of books, sermons and speeches. But he rarely got credit for another important aspect of his legacy: having done more than anyone before him to turn the Vatican around on clergy sexual abuse.

As cardinal and pope, Benedict pushed through revolutionary changes to church law to make it easier to defrock predator priests, and he sacked hundreds of them. He was the first pontiff to meet with abuse survivors. And he reversed his revered predecessor on the most egregious case of the 20th century Catholic Church, finally taking action against a serial pedophile who was adored by St. John Paul II’s inner circle.

But much more needed to be done, and following his death Saturday, abuse survivors and their advocates made clear they did not feel his record was anything to praise, noting that he, like the rest of the Catholic hierarchy, protected the image of the institution over the needs of victims and in many ways embodied the clerical system that fueled the problem.

“In our view, Pope Benedict XVI is taking decades of the church’s darkest secrets to his grave with him,” said SNAP, the main U.S.-based group of clergy abuse survivors.

Matthias Katsch of Eckiger Tisch, a group representing German survivors, said Benedict will go down in history for abuse victims as “a person who was long responsible in the system they fell victim to,” according to the dpa news agency.

In the years after Benedict’s 2013 resignation, the scourge he believed encompassed only a few mostly English-speaking countries had spread to all parts of the globe. Benedict refused to accept personal or institutional responsibility for the problem, even after he himself was faulted by an independent report for his handling of four cases while he was Munich bishop. He never sanctioned any bishop who covered up for abusers, and he never mandated abuse cases be reported to police.

But Benedict did more than any of his predecessors combined, and especially more than John Paul, under whose watch the wrongdoing exploded publicly. And after initially dismissing the problem, Pope Francis followed in Benedict’s footsteps and approved even tougher protocols designed to hold the hierarchy accountable.

“He (Benedict) acted as no other pope has done when pressed or forced, but his papacy (was) reactive on this central issue,” said Terrence McKiernan, founder of the online resource BishopAccountability, which tracks global cases of clergy abuse and cover-up.

As prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith for a quarter-century, the former Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger saw first-hand the scope of sex abuse as early as the 1980s. Cases were arriving piecemeal to the Vatican from Ireland, Australia and the U.S., and Ratzinger tried as early as 1988 to persuade the Vatican legal department to let him remove abuser priests quickly.

Vatican law at the time required long and complicated canonical trials to punish priests, and then only as a last resort if more “pastoral” initiatives to cure them failed. That approach proved disastrous, enabling bishops to move their abusers around from parish to parish where they could rape and molest again.

The legal office turned Ratzinger down in 1988, citing the need to protect the priest’s right to defense.

In 2001, Ratzinger persuaded John Paul to let him take hold of the problem head on, ordering all abuse cases be sent to his office for review. He hired a relatively unknown canon lawyer, Charles Scicluna, to be his chief sex crimes prosecutor and together they began taking action.

“We used to discuss the cases on Fridays; he used to call it the Friday penance,” recalled Scicluna, Ratzinger’s prosecutor from 2002 to 2012 and now the archbishop of Malta.

Under Ratzinger’s watch as cardinal and pope, the Vatican authorized fast-track administrative procedures to defrock egregious abusers. Changes to church law allowed the statute of limitations on sex abuse to be waived on a case-by-case basis; raised the age of consent to 18; and expanded the norms protecting minors to also cover “vulnerable adults.”

The changes had immediate impact: Between 2004 and 2014 — Benedict’s eight-year papacy plus a year on either end — the Vatican received about 3,400 cases, defrocked 848 priests and sanctioned another 2,572 to lesser penalties, according to the only Vatican statistics ever publicly released.

Nearly half of the defrockings occurred during the final two years of Benedict’s papacy.

“There was always a temptation to think of these accusations of this scourge as something that was contrived by the church’s enemies,” said Cardinal George Pell of Australia, where the allegations hit early and hard and where Pell himself was accused of abuse and of dismissing victims.

“Pope Benedict realized very, very clearly that there is an element of that, but the problem was much, much deeper, and he moved effectively toward doing something about it,” said Pell, who was eventually acquitted of an abuse conviction after serving 404 days in solitary confinement in a Melbourne lockup.

Among the first cases on Ratzinger’s agenda after 2001 was gathering testimony from victims of the Rev. Marcial Maciel, the founder of the Mexico-based Legionaries of Christ religious order. Despite volumes of documentation in the Vatican dating from the 1950s showing Maciel had raped his young seminarians, the priest was courted by John Paul’s Curia because of his ability to bring in vocations and donations.

“More than the hurt that I received from Maciel’s abuse, later on, stronger was the hurt and the abuse of power from the Catholic Church: the secrecy, ignoring my complaints,” said Juan Vaca, one of Maciel’s original victims who along with other former seminarians filed a formal canonical case against Maciel in 1998.

Their case languished for years as powerful cardinals who sat on Ratzinger’s board, including Cardinal Angelo Sodano, John Paul’s powerful secretary of state, blocked any investigation. They claimed the allegations against Maciel were mere slander.

But Ratzinger finally prevailed and Vaca testified to Scicluna on April 2, 2005, the very day that John Paul died.

Ratzinger was elected pope two weeks later, and only then did the Vatican finally sanction Maciel to a lifetime of penance and prayer.

Benedict then took another step and ordered an in-depth investigation into the order that determined in 2010 that Maciel was a religious fraud who sexually abused his seminarians and created a cult-like order to hide his crimes.

Even Francis has credited Benedict’s “courage” in going after Maciel, recalling that “he had all the documentation in hand” in the early 2000s to take action against Maciel but was blocked by others more powerful than he until he became pope.

“He was the courageous man who helped so many,” Francis said.

That said, Benedict’s protocol-bending courage only went so far.

When the archbishop of Vienna, Cardinal Christoph Schoenborn, publicly criticized Sodano for having blocked the Vatican from investigating yet another high-profile serial abuser — his predecessor as Vienna archbishop — Benedict summoned Schoenborn to Rome for a dressing down in front of Sodano. The Vatican issued a remarkable reprimand taking Schoenborn to task for having dared speak the truth.

And then an independent report commissioned by his former diocese of Munich faulted Benedict’s actions in four cases while he was bishop in the 1970s; Benedict, by then long retired as pope, apologized for any “grievous faults” but denied any personal or specific wrongdoing.

In Germany on Saturday, the We are Church pro-reform group said in a statement that, with his “implausible statements” about the Munich report, “he himself seriously damaged his reputation as a theologian and church leader and as an ‘employee of the truth.’”

“He was not prepared to make a personal admission of guilt,” it added. “With that, he caused major damage to the office of bishop and pope.”

The U.S. survivors of the Road to Recovery group said Benedict as cardinal and pope was part of the problem. “He, his predecessors, and current pope have refused to use the vast resources of the church to help victims heal, gain a degree of closure, and have their lives restored,” the group said in a statement calling for transparency.

But Benedict’s longtime spokesman, the Rev. Federico Lombardi, says Benedict’s action on sex abuse was one of the many underappreciated aspects of his legacy that deserves credit, given that it paved the way for even more far-reaching reforms.

Lombardi recalled the prayers Ratzinger composed in 2005 for the Good Friday Via Crucis procession at Rome’s Colosseum as evidence that the future pope knew well — earlier and better than anyone else in the Vatican — just how bad the problem was.

“How much filth there is in the church, especially among those who, in the priesthood, are supposed to belong totally to him (Christ),” Ratzinger wrote in the meditations for the high-profile Holy Week procession.

Lombardi said he didn’t understand at the time the experience that informed Ratzinger’s words.

“He had seen the gravity of the situation with far more lucidity than others,” Lombardi said.

___

Follow AP’s coverage of the death of Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI at https://apnews.com/hub/pope-benedict-xvi

BY JAMES BICKERTON

Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI, who led the Catholic Church for eight years between 2005 and 2013, has passed away aged 95 at his residence in the Vatican.

Benedict was known to be very unwell, with Pope Francis describing him as "very sick" on Wednesday, and asking for prayers to help his successor "to the very end."

In February 2013 Benedict, a theological conservative, shocked the world by announcing he would become the first pope to abdicate from the post since Gregory XII in 1415. After stepping down, and being replaced by Pope Francis, he continued to live within the Vatican, adopting the name Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI after his resignation.

Benedict was born Joseph Ratzinger on 16 April 1927 in the German Weimar Republic. He had a turbulent childhood, which saw the rise of the Nazis and World War II. Benedict was conscripted into the Hitler Youth and lost a 14-year-old cousin with Down syndrome, who was taken away by the Nazis as part of their eugenics program and shortly after declared dead.

The future pope began his service to the Catholic church in 1951, when he was appointed chaplain at the parish St. Martin, Moosach, in Munich. He went on to become a professor at the University of Bonn and later held a number of other posts at the universities of Munster, Tubingen and Regensburg.

Initially seen as a reformer, Benedict became increasingly conservative, particularly after the Western world was rocked by a series of mass protests, some violent, in 1968.

In 1977 Benedict was appointed as Archbishop of Munich and Freising, and four years later received the post of Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith from Pope John Paul II, making him responsible for rooting out heresy within the church. He was promoted to Cardinal Bishop of Velletri-Segni in 1993, and continued to make his way up the church hierarchy until he was elected as the 265th pope in 2005, at the age of 78, following the death of Pope John Paul II.

Speaking to Newsweek Professor Michele Dillon, a sociologist at the University of New Hampshire and an expert in Catholicism, argued Benedict's legacy will be "overshadowed" by some of his socially conservative views.

She said: "I think Benedict's legacy will always be overshadowed in public opinion by his long tenure as Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, his role as the moral enforcer of the Church's re-stated opposition to gay rights, women's ordination, contraception and abortion.

"Even as pope—while he did not focus on these issues, but instead on the principles of love, social justice and the common good—his personal reserve and intellectualism got in the way of his ability to connect with ordinary Catholics."

Professor Megan Armstrong, who teaches Catholic history at Canada's McMaster University, described Benedict as a "social conservative and papal traditionalist," from a tradition which "embraces broad differences in conceptions of papal and priestly authority, clerical celibacy, the role of women, sexuality and many other issues."

However, Benedict's "single-minded pursuit of his theological vision blinded him to the serious pastoral problems that beset the Church," according to the University of Southern California's Sheila Briggs, an associate professor of religion and gender studies.

A bombshell report into child sexual abuse within the Catholic Church in Germany, published earlier in 2022, concluded Benedict had knowingly failed to take action against priests involved in four cases of abuse, during his time as Archbishop of Munich.

In response Benedict released a statement, expressing his "deep sorrow" and "heartfelt request for forgiveness."

Responding to the report Andrea Tornielli, the editorial director for the Vatican's Dicastery for Communication, claimed Benedict had imposed "very harsh norms against clerical abusers" both as Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, and then as pontiff.

Speaking to Newsweek Briggs said that as Archbishop of Munich Benedict had disciplined "politically activist priests, while ignoring clerical sex abusers," which she said contributed to the Church's "worst crisis since the 16th century Reformation."

She concluded: "Benedict had a superb intellect and an acute theological mind, was capable of personal empathy, but had an exceedingly poor grasp of the world in which he lived."

Dillon added the Munich report "contributes to the view" that Benedict was "aloof in regard to the everyday realities of Catholics, including sex abuse victims."

However, she did note he was the "first pope to actually formally apologize to Catholics for the sex abuse of priests and bishops," which he did in a March 2010 letter to Irish Catholics.

Pope Benedict's full history with Vladimir Putin

James Lewis Heft from the University of Southern California, told Newsweek Benedict was "the first pope to take the sexual abuse crisis seriously."

He described the former pope as a "brilliant theologian." Heft added Benedict's decision to stand down in 2013 was "a great act of courage and realism," and that "he was more comfortable in the library than in the Vatican."

Speaking to Newsweek Professor Kathleen Cummings, director of the Cushwa Center for the Study of American Catholicism, described Benedict as "a man of unwavering faith, deep conviction and towering intellect who indelibly shaped the church."

She concluded: "For the time being, we await a papal funeral without a conclave, an unprecedented event that mirrors the experience of March 2013, a conclave without a papal funeral."

Pope Benedict XVI led the Catholic Church at a crucial time and had to confront a growing sexual abuse scandal.

Mathew Schmalz, College of the Holy Cross

Benedict XVI leaves behind a complex legacy as a Pope and theologian.

To many observers, Benedict, who died on Dec. 31, 2022 at the age of 95, was known for criticizing what he saw as the modern world’s rejection of God and Christianity’s timeless truths. But as a scholar of the diversity of global Catholicism, I think it’s best to avoid simple characterizations of Benedict’s theology, which I believe will influence the Catholic Church for generations.

While the brilliance of this intellectual legacy will certainly endure, it will also have to contend with the shadows of the numerous controversies that marked Benedict’s time as pope and, later, as pope emeritus.

Priest and professor

Benedict was born Josef Alois Ratzinger on April 16, 1927, in Marktl am Inn, Germany. During World War II, he was required to join the Hitler Youth, a wing of the Nazi Party. He was later drafted into an anti-aircraft unit and then the infantry of Nazi Germany.

In 1945, he deserted the German military and was held as a prisoner of war by the Americans; he was released when World War II concluded. In 1946, he went to study for the priesthood and was ordained five years later. He completed his doctorate in theology in 1953.

While teaching at the University of Bonn, Ratzinger was chosen as a theological adviser to Cardinal Joseph Frings of Cologne, a strong critic of Nazism, for the Second Vatican Council held between 1962 and 1965. The Second Vatican Council attempted to renew the Catholic Church by engaging the modern world more constructively. At the council, Ratzinger argued that Catholic theology needed to develop a “new language” to speak to a changing world.

As pope, Benedict would later reject more progressive interpretations of the council as a revolutionary event that was intended to remake the Catholic Church. While the council did bring substantial changes to Catholic life, particularly by allowing mass in local languages, Benedict resisted any suggestion that the Second Vatican Council was calling for a fundamental break with centuries-old Catholic doctrine and tradition. And during his pontificate, he would permit wider celebration of the old Latin Mass – a decision that his successor Pope Francis would later reverse

In 1966, Ratzinger accepted an important teaching position at the University of Tubingen. During the late 1960s, Tubingen saw widespread student protests, some of which called for the Catholic Church to become more democratic. When protesting students disrupted the Tubingen faculty senate, Ratzinger reportedly walked out instead of speaking with students as other faculty did. Ratzinger was disturbed by what he felt were dictatorial and Marxist tendencies among the student protesters. Ratzinger then moved to the University of Regensberg.

In 1977, he was named bishop of Munich and Freising by Pope Paul VI. Soon after, he was named a cardinal, a member of the administrative body that elects the pope.

Cardinal and pope

As a skilled theologian, Ratzinger was chosen by Pope John Paul II to head the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, which oversees and enforces Catholic doctrine. In this position, Cardinal Ratzinger disciplined a number of theologians. Most notable was the case of American priest and theologian Charles Curran, who was fired from The Catholic University of America because he challenged official Catholic teachings on sexuality.

Ratzinger was also chosen to head the committee drafting The Catechism of the Catholic Church. Published in 1992, The Catechism remains an important foundation for any understanding of Catholic thought and practice.

After John Paul II’s death in 2005, Ratzinger was elected pope. He chose the name “Benedict” in honor of Benedict of Nursia, the founder of Western monasticism, a religious movement that preserved Western culture after the fall of Rome. The name “Benedict” also acknowledged Benedict XV, a much-overlooked pope who tried to broker a peace agreement to end the First World War.

Controversies in the pontificate

After his election, Pope Benedict XVI had to confront a growing sexual abuse scandal in the Catholic Church. While a cardinal, he had publicly downplayed the extent and seriousness of the crisis. And it was under his leadership that The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith decided not to remove Lawrence C. Murphy from the priesthood, even though Murphy had been accused of molesting more than 200 boys at a Catholic school for the deaf in Wisconsin.

As pope, however, Benedict did take some strong steps that his predecessor, John Paul II, did not. Most significantly, Benedict punished Marcial Maciel Degollado, an incestuous bigamist, serial pedophile and the powerful founder of the Legionaries of Christ, an important Catholic religious order, by taking away his permission to preach or to say Mass publicly. He also criticized Irish bishops for their mishandling of the sexual abuse crisis.

For many survivors of clerical sexual abuse, these actions were not nearly enough. Benedict did not move to open Vatican records to public investigation, and he also failed to discipline cardinals and bishops who reassigned pedophile priests.

Beyond the sexual abuse crisis, Benedict’s pontificate had other controversies that drew worldwide attention. During a lecture in Regensberg in 2006, Benedict seemed to criticize the Islamic view of God and the legacy of the Prophet Muhammad. This lecture led to protests in the Middle East and South Asia. However, his official visits to Beirut and Istanbul repaired some of the damage.

Benedict also reached out to Catholic splinter groups. In 2009, he lifted the excommunication of bishops of the order of St. Pius X, a breakaway Catholic sect that rejects the reforms of the Second Vatican Council. After doing this, Benedict learned that one St. Pius X bishop, Richard Williamson, had made antisemitic comments and denied the holocaust.

Benedict said his lack of knowledge about Williamson’s views was an “unforeseen mishap” due to a lack of familiarity with the internet as a “source of information.”

Theological writings

As pope, Benedict continued his theological writing and produced three important encyclicals or papal letters.

The first encyclical, Deus Caritas Est, or “God is Love,” defends “charity” as love that is freely given. Charity is not simply a good deed but an act that changes both the giver and the recipient.

The second encyclical, Spe Salvi, or “Saved in Hope,” reflects upon the hope that God gives human beings in a world that often seems hopeless.

In the third encyclical, Caritas in Veritate, or “Charity in Truth,” Benedict argues that charity is fundamentally related to justice. And when it comes to questions of human progress and fulfillment, we cannot place our trust in the nation state or market economies because “without God, man neither knows which way to go, nor even understands who he is.”

These papal letters attempt to defend Christianity in a world that Benedict believed was growing increasingly hostile to religious faith. What was striking about Benedict’s thought – even to his theological critics – was how elegantly he presented his case for Christ and Christianity’s transforming power as sources of truth, beauty and love. But long before he became pope, Benedict admitted that Christianity would continue to lose cultural ground and dwindle to an ever smaller group of faithful believers. Writing in 1969, Ratzinger predicted the Church would have “to start afresh from the very beginning,” which meant that someday Christianity would have to build itself up again from its foundations.

The legacy of Benedict XVI

When Benedict resigned as pope in 2013, it took the world by surprise. In saying that he could no longer bear the burdens of the Papacy, Benedict promised to live in seclusion. His official title became “Pope Emeritus.”

But controversy also followed his resignation. For example, he gave interviews and put his name on writings that appeared to criticize the reforms of Pope Francis, who succeeded him.

Most recently, a January 2022 report on sexual abuse in the diocese of Munich criticized Ratzinger’s “inaction” regarding four cases of sexual abuse during his period as archbishop from 1977 to 1982. In reaction to the report, the pope emeritus apologized but did not admit to any administrative failures.

Benedict XVI’s writings will be relevant decades from now, but his pontificate will inevitably be associated with controversies. As for his own personal legacy, that will likely be defined by the one issue that concerned Benedict the most: how the Catholic Church can still make a difference in the modern world.

Mathew Schmalz, Professor of Religious Studies, College of the Holy Cross

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Pope Benedict XVI, elected a philosopher king, was at heart a German professor

In 2005, the cardinals thought they were electing the smartest man in the room. They should instead have sought the man who would listen to all the other smart people in the church.

(RNS) — The cardinals who voted for Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger at the 2005 papal conclave believed they were electing the smartest man in the room. Just as Plato believed that a philosopher king would be the best ruler, they thought that a brilliant theologian would be the best pope.

The church is still debating the cardinals’ wisdom. Benedict became an ecclesial Rorschach test, and opinions on his effect on the church ultimately say more about the speaker than the pope himself: Those who approve of Benedict are marked as conservatives; those who consider his papacy a mistake are classified as progressives. Nuanced analysis is difficult.

As a young theologian, Ratzinger advised German bishops promoting reform at the Second Vatican Council. He ghostwrote a speech severely criticizing the Holy Office, the Vatican department responsible for defending the faith, which he would one day lead. He called its methods of silencing prominent theologians prior to the council “a source of scandal to the world.”

In these early days, Ratzinger was friends with liberal theologian Hans Küng, who helped him get a professorship at the University of Tübingen in 1966. Student demonstrations there in 1968 soured Ratzinger on the progressive movement, which he saw as turning away from orthodox Catholic theology.

In 1969, Ratzinger abandoned Tübingen for the more conservative University of Regensburg. Ratzinger preferred docile students to those who challenged him. He avoided the rough and tumble of academic debate. You would not see Ratzinger at academic conferences where he could be challenged by his peers.

He did have a loyal following of former graduate students who met with him periodically through the years to discuss theological issues. Even after being appointed archbishop of Munich in 1977, he continued to direct his doctoral students who had not finished their dissertations.

But it was always clear he was the teacher. A Jesuit who brought a group of Americans to meet Benedict at a papal audience introduced the pope as “my friend.” The pope corrected him, “You were my student, not my friend.”

Ratzinger was a prolific writer. His popular “Introduction to Christianity,” published in 1968, brought him to the attention of Pope John Paul II, who in 1981 appointed him prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, the successor to the Holy Office he had so vehemently criticized.

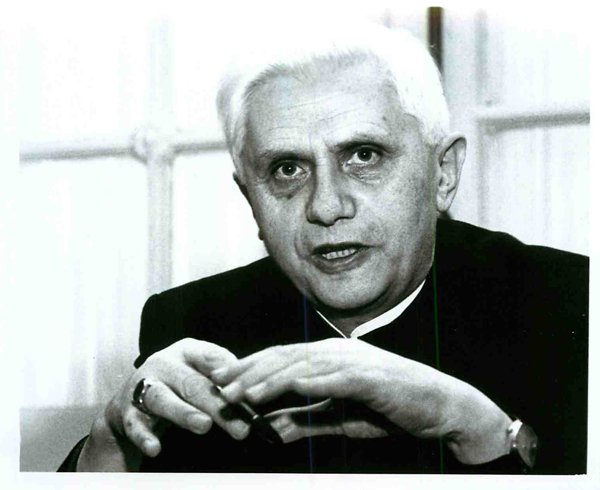

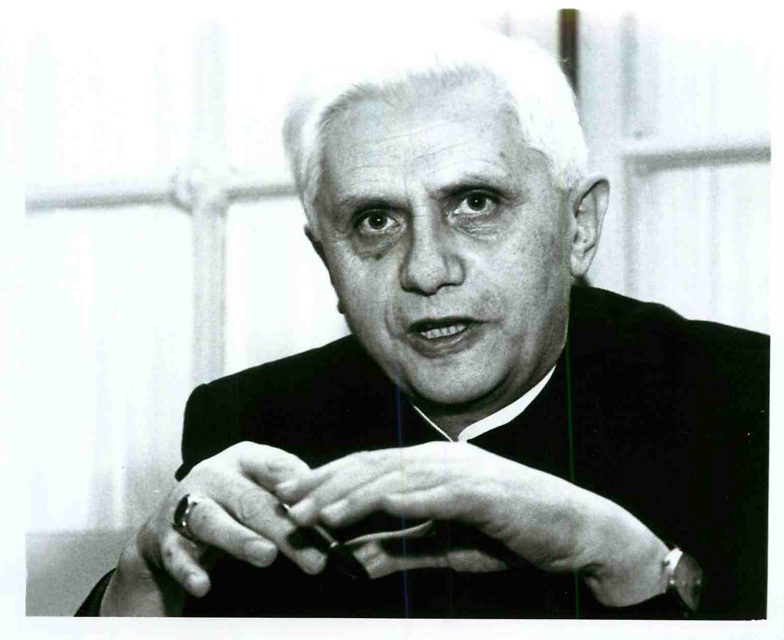

New York – The Vatican’s chief theologian, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, gave a 50 minute talk at St. Peter’s Lutheran Church on Jan. 27, 1988. He blamed contemporary biblical scholars for diluting the teaching of the Church. Ratzinger’s presentation was interrupted by a dozen gay and lesbian activists who sprang to their feet and shouts “Facist! Stop the inquisition!” RNS file photo by Odette Lupis.

As head of the congregation, Ratzinger did many of the same things he had earlier warned against. He treated theologians to the kind of correction he used to apply to his students. If they did not follow his view of orthodoxy, he “flunked” them, taking away their authority to teach and publish. He would also stop the appointment of any bishop he considered suspect.

(Full disclosure: I was forced to resign as editor of America magazine at the insistence of Ratzinger, a story I relate in a separate column.)

He was especially critical of moral theologians in the United States, liberation theologians in Latin America and interreligious theologians in Asia. Also carefully watched were writings on priestly ministry, especially any thoughts on women’s ordination or optional celibacy. Any criticism of church authority was suppressed.

The suppression of theological debate under the papacies of John Paul and Benedict was disastrous for the church. The creative rethinking of church teaching begun at Vatican II was squashed. Rather than finding new ways to explain the faith to people in the 21st century, the church repeated formulas many found meaningless.

Papal teaching about women was especially repugnant to educated women, who saw the church as protecting patriarchal values. Describing homosexuality as “intrinsically disordered” was grating, especially to young people.

These papacies also attracted to the priesthood a cadre of young men whose clerical style would be off-putting to many, especially women.

By electing the smartest man in the room, the cardinals had chosen someone who was not interested in listening to people who had other views. A smart leader surrounds himself with people who supplement his weaknesses, not with people who always agree with him. Benedict XVI’s great failing was surrounding himself with acolytes who would never challenge him and would insulate him from challenge.

This got him into trouble when he acted on his own without consulting experts. When he spoke of Muslims at Regensburg in 2006, he said things that they found insulting. But rather than consulting Archbishop Michael L. Fitzgerald, the Vatican’s expert on Islam, he exiled him to Egypt as nuncio. (Francis made Fitzgerald a cardinal in 2019.)

Benedict angered many Protestant leaders in 2007 when he said that only the Catholic and Orthodox churches were true churches because they had legitimate bishops — the others, he said, are only “ecclesial communities.” Jews were upset when he lifted the excommunication of antisemitic schismatic bishops in 2009.

In both instances, problems could have been lessened if he had consulted ecumenical and interreligious experts before acting.

Pope Benedict XVI, formerly known as Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger of Germany, greets a roaring crowd upon his introduction as the Roman Catholic Church’s new pontiff. Photo by Grzegorz Galazka.

Benedict’s heart was in the liturgy and spirituality of the past, which attracted only a minority of Catholics, let alone those outside the church. For the liturgy, he ignored the advice of translation experts, preferring literal translations that read as if they had been run through Google translations and were difficult to understand when read out loud.

The Benedict papacy did advance the church in its handling of clerical sex abuse. I suspect there were a lot more cases of sex abuse in Munich while he was archbishop than were ever revealed, but as head of the Congregation for Doctrine of the Faith, he did listen to American bishops’ concerns when other cardinals stonewalled them.

When his congregation was assigned abuse cases, the disciplinarian tendencies that led him to police theologians allowed him to cut through canonical niceties to expel hundreds, perhaps thousands, of abusers from the priesthood. His response was never perfect, but he did understand and deal with the problem quicker than any other Vatican official, including John Paul. As pope, he met with victims of abuse but did little to deal with bishops who had covered up their crimes.

He also listened to the international experts in the Secretariat of State, which kept him from making mistakes in foreign affairs. Here he was not an innovator, but continued the Vatican line of his predecessors. He upheld the social teaching of the church and began dealing with climate change, but these were never a principal focus of his papacy.

Benedict also made the critical decision to subject the Vatican finances to review by Moneyval, the international agency created to stop money laundering and the financing of terrorism. This was the first time the Vatican opened itself to review by an outside body. Because of Benedict, Moneyval periodically reviews and publicly reports on the Vatican’s progress, or lack of it, on financial reform.

Finally, Benedict dramatically changed the papacy by resigning, making it possible for popes to resign in the future. What in the past was unthinkable, now is acceptable.

Benedict was a humble man who wanted what was best for the church. He trusted that the Holy Spirit could guide the church without him. He supported his successor and for the most part stayed silent, though supporters and detractors tried to spin his few statements as attacks on Francis.

No doubt there will be a conservative movement to canonize Benedict with cries of “santo subito” — “sainthood now” — as a way of carving his teachings in stone. I oppose the canonization of any pope, but I have no doubt he is in heaven. If I had to place a bet, I would predict that Benedict and Francis will be canonized on the same day, just as John Paul II and John XXIII were. That is what unity looks like in the Catholic Church.

My encounters with Joseph Ratzinger — and Pope Benedict XVI

Open discussion was suppressed by Ratzinger under the papacy of John Paul. If you did not agree with the Vatican, you were silenced.

(RNS) — I first met Joseph Ratzinger in June 1994 when he was the cardinal prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. No, I was not being interrogated by the Grand Inquisitor. This was long before I got in trouble with the Vatican as editor-in-chief of America magazine. I was in Rome to interview him and other church officials for my book, “Inside the Vatican: The Politics and Organization of the Catholic Church.”

I almost missed the interview. Cardinal Ratzinger was sick the day of our appointment. When I arrived, I was asked whether I wanted to meet with the congregation’s secretary. I agreed, figuring it was better than nothing. When I was ushered into his presence, I hadn’t gotten a word out before the secretary, Archbishop Alberto Bovone, assaulted me with questions: “Who are you?” “What are you doing here?” “I will decide whether you can see Cardinal Ratzinger.”

“But the cardinal already agreed to see me,” I stuttered. That meant nothing to him; he demanded a list of questions I was going to ask. He then assigned a young Dominican to interrogate me.

Jesuits being interrogated by Dominicans working for the Inquisition has a long and unhappy history. On the other hand, Dominicans have also come to our rescue. When Lorenzo Ricci, the Jesuit superior general died in 1775 after being imprisoned in Rome’s Castel Sant’Angelo by the pope, the top Dominican was the only one willing to preside at his funeral. The tradition has continued ever since.

In any case, I was handed over to the Dominican, who, it seemed, was already on my side. During my interrogation by Bovone, he had been making faces and rolling his eyes behind the secretary’s back. Rather than interrogate me, he advised me on what to do. “Write a letter to the cardinal. Explain that you are leaving at the end of the week and that you would like to meet with him for 15 minutes.”

I wrote the letter as soon as I got back to my room, faxed it to the CDF and got a new appointment. Ratzinger agreed to meet with me in the afternoon, when Vatican offices are usually closed. The interview went more than an hour.

Thomas Reese, S.J., during the 2005 conclave in front of Castel Sant’Angelo, where Lorenzo Ricci, the Jesuit superior general, was imprisoned by the pope in the 1770’s. Photo by Thomas J. Koller, S.J.

I learned a lot about Ratzinger before the interview even began. He was kind and willing to go out of his way to help a young scholar, even at a time he was not feeling well.

On the other hand, having a bully as his No. 2 man showed either blindness on Ratzinger’s part or an unhealthy dependence on people who, though loyal, were not fit for their jobs. Neither as prefect nor as pope was he good at choosing his subordinates.

When we sat down for the interview, Ratzinger asked whether I wanted to do it in German or Italian. With a panicked voice I said, “English would be much better.” He agreed, saying “My English is very limited.” In fact, it was excellent. Only once during the interview did he struggle for a word.

He told me that he was at first undecided whether to accept the position as head of the congregation. Pope John Paul II had to ask him three times before he said yes.

“Give me time, Holy Father,” he told John Paul. “I am a diocesan bishop; I have to be in my diocese.” He ultimately agreed to come to Rome in 1982.

In our interview, he spoke of fostering a dialogue between theologians and his office, but theologians who lost their jobs or were silenced by him did not experience it that way. He was upset by the insulting language of attacks on his office, even if he could laugh at the situation.

(I should have remembered this years later before foolishly referring to the “inquisitional” procedures of his congregation in an editorial in America.)

What is most striking about the interview today was his admission, “I do not have charism about structural problems.”

In other words, Ratzinger was at heart a scholar not a manager, but he would become head of a billion-member organization with a hierarchical structure and a complex bureaucracy in Rome.

In 1998, after my book was published, I became editor in chief of America, a magazine first published by Jesuits in 1909. My goal was to make it “A magazine for thinking Catholics and those who want to know what Catholics are thinking.”

Although almost always careful in editorials to stick to the Vatican line, I thought I could publish alternative views in the opinion section of the magazine if I insisted that these articles did not necessarily represent the views of the magazine. We were, after all, a journal of opinion.

During my seven years as editor, the CDF published important documents on which I asked relevant scholars to comment. They usually praised the parts they liked, and criticized those they did not. I was always happy to publish critical responses to these articles.

I also published articles by many bishops and cardinals, including then Archbishop Raymond Burke, whom I invited to explain why the church should deny Communion to pro-choice Catholic politicians. I asked Chicago Cardinal Francis George, a prominent conservative, a half dozen times to write something for us, but he always refused.

A high point of the magazine as a forum for dialogue was a submission by Cardinal Walter Kasper, the head of the Vatican ecumenical office, criticizing the ecclesiology of Cardinal Ratzinger. As the article was going to the printers, I sent a copy to Ratzinger inviting his response. At first, he declined, but later changing his mind, sent a response in German, which we had translated and published.

We were delighted to have two prominent cardinals debating an important issue in the pages of America, but later I learned that Cardinal George complained about the exchange and asked the Vatican Secretary of State to tell the cardinals not to debate in America because it scandalizes the faithful.

Despite my attempts to be fair, it became apparent that neither John Paul nor Cardinal Ratzinger wanted a journal of opinion unless it reflected their opinions. After two and a half years as editor, I heard from the Jesuit superior general, Peter-Hans Kolvenbach, that the Vatican was unhappy with an article on AIDS and condoms written by Jesuit theologian James Keenan and Jesuit physician Jon Fuller.

I would have been happy to publish a rebuttal from anyone in the Vatican, but I never received anything directly from the congregation. The congregation always communicated with me through my Jesuit superiors.

In June 2001, I was told that the congregation found “Father Reese’s way of criticizing the Holy See, and particularly the congregation, aggressive and offensive.” In particular, they took issue with an editorial we ran on due process in the church (April 9, 2001). We were accused of being anti-hierarchical.

At the end of February 2002, Father Kolvenbach said that CDF had decided to impose a commission of ecclesiastical censors on America “at the request of American bishops and the nuncio.” The censors would be three American bishops.

Not only was this a bad idea, it was totally impractical, since we published weekly.

In April I received a list of items published in America that the congregation did not like. They included a book review by Jesuit historian John O’Malley of “Papal Sins,” the article by Keenan and Fuller, an article on homosexual priests by Jesuit James Martin and articles on the CDF document, “Dominus Iesus,” by Francis X. Clooney, Michael A. Fahey, Peter Chirico, and Francis A. Sullivan.

Ratzinger seemed to have a thin skin when it came to documents coming out of his congregation.

Only two editorials were mentioned — one on “Dominus Iesus” (Oct. 28, 2000) and the other on “the abortion pill,” RU-486 (Oct. 14, 2000). We condemned the abortion drug but hinted that it might be time to rethink the church’s teaching on birth control as a way of reducing the number of abortions.

Interestingly, America’s extensive and forceful coverage of the sex abuse crisis was never mentioned by the congregation, though I knew that some American bishops did not like it. Ratzinger, although not perfect, was better than anyone else in Rome on the topic.

No one could tell me which U.S. bishops had requested the censorship board. I knew it had never come up at a meeting of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. Nor was it discussed at the USCCB’s administrative committee, according to my sources, among them Archbishop Thomas Kelly, who was on the committee during this time.

When I asked Bishop Donald Trautman, chair of the USCCB Committee on Doctrine, he grew furious that a censorship board was set up without consulting his committee. He planned to object vigorously.

Nor was American Archbishop John Foley, head of one of the communications offices in the Vatican, consulted. He said that, if he were asked, he would have said it was a bad idea. He jokingly referred to himself as the “left wing of the Roman curia.”

I asked for help from Archbishops Kelly, John Quinn and Daniel Pilarczyk, but they all said that they were not trusted by Rome, so their support would do no good. Quinn and Pilarczyk had been presidents of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops and Kelly had been conference general secretary and on the staff of the papal nunciature in Washington.

I approached Jesuit Cardinal Avery Dulles, who thought a censorship board was a terrible idea. He promised to put in a good word for me with Ratzinger. “You publish me,” the very orthodox cardinal said.

Sometime before the end of July 2003, Kolvenbach met with Ratzinger and was able to talk him out of imposing a censorship board. Kolvenbach warned me that the congregation would be watching to see how America responded to CDF’s upcoming document on gay marriage. I asked Associate Editor James Martin, who had written extensively on gays in the church, not to say anything about the document. I wanted to protect him and the magazine. He agreed.

Our first article on the subject was on June 7, 2004, by Monsignor Robert Sokolowski, a philosopher at the Catholic University of America, who was strongly opposed to gay sex and gay marriage. I had to talk him into dropping a paragraph comparing gay sex to sex with animals.

His article, not surprisingly, elicited strong responses, one of which came from Stephen Pope, professor of theology at Boston College. Even though I got Pope to tone the article down a notch, and even though I allowed Sokolowski to respond to Pope in the same issue, I knew as it went to the printers that this could be the final nail in my coffin.

Although I had never opined or editorialized on the topic, it was clear that merely allowing a discussion of some issues in America was more than Ratzinger would tolerate.

Almost immediately after the publication of the December 6, 2004, issue, my American superior heard complaints from the papal nuncio in Washington. He also complained about an article on politicians, abortion and Communion by U.S. Representative Dave Obey, who had been denied Communion by Burke. There was acknowledgement that we published articles on both sides of the “wafer war.”

As 2005 progressed, the world focused on the sickness and death of John Paul and the conclave that elected Ratzinger Pope Benedict XVI. During this time, I was busy working with the media explaining and commenting on what was happening.

Before the conclave, at an off-the-record dinner with some journalists in Rome, I was asked, “What would be your reaction if Ratzinger was elected pope?” I responded, “How would you feel if Rupert Murdoch took over your newspaper?”

On the day of Ratzinger’s election, I had already promised to appear on the PBS Newshour. On the program, I blandly opined that some people will like the results, some won’t. After that, my response to press inquiries was “no comment,” because I believed that his election was a disaster but, as Jesuit, I could not say so.

On April 19, 2005, as I heard the announcement of Ratzinger’s election in St. Peter’s Square, I knew my tenure as editor of America was over. For the good of the magazine and the good of the Jesuits, I had to go. In addition, after seven years of looking over my shoulder, I had had enough.

I stopped giving interviews and left Rome.

When I got back to New York, the other Jesuits at the magazine would not let me resign. A few days later, I met with my superior, the president of the Jesuit Conference, and learned that my time as editor was over. Only then did I learn that back in March, Ratzinger had told the Jesuit superior general that I had to go. For various reasons they had not gotten around to telling me. So I resigned.

My Jesuit superiors had always been very supportive of my work, but I knew that ultimately, they could not protect me unless I was willing to compromise my values as an editor. They had not been able to protect numerous Jesuit theologians who had been disciplined by CDF.

When the news hit the press, I was portrayed as Benedict’s first victim; the truth was, I was the last victim of Cardinal Ratzinger. Because I was so well known by the media, who had frequently used me as a source, the coverage was extensive and negative toward the new pope.

The coverage was so bad that the Vatican stepped back from the planned removal of the Jesuit editor of the German journal, “Stimmen der Zeit” (“Voices of the times”). They let him serve out his term as editor.

If I were a unique case, my story would be interesting but not important in judging the legacy of Joseph Ratzinger. Sadly, mine is only one of hundreds of examples of the repression of free inquiry by reporters and theologians during the papacies of John Paul and Benedict.

A few months before my resignation, Jacques Dupuis, a distinguished theologian who had been disciplined by Ratzinger, told us the story of his own meeting. After the congregation had condemned one of his books, the elderly (and ill) theologian prepared a 200-page response. When he met with Ratzinger and the CDF, he told the editors of America, they surprised him by asking him for his response. When he pointed to the document on the table before them, which had taken him months of work, they scoffed, “You don’t think we’re going to read that, do you?” Dupuis died not long after our meeting.

Whether I was right or wrong in my views is irrelevant. What matters is that after the Second Vatican Council open discussion was suppressed by Ratzinger under the papacy of John Paul. If you did not agree with the Vatican, you were silenced. Yet, without open conversation, theology cannot develop, and reforms cannot be made. Without open debate, the church cannot find ways of preaching the gospel in ways understandable to people of the 21st Century.

The papacy of Pope Francis has reopened the windows of the church to allow the fresh breeze of the Spirit. Conversation and debate is possible again, even to disagreeing with the pope. Unlike his predecessors, Francis does not silence his critics. Change will not happen quickly enough for many in the church, but allowing the conversation to flourish is essential to preparing for reform.

For Conservative Catholics in U.S., Pope Benedict’s Death Is Loss of a Hero

Even after his retirement a decade ago, the former pope remained the unofficial figurehead of the conservative wing of the American church.

Pope Benedict XVI at St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican after being elected by the conclave of cardinals in 2005.Credit...Mario Tama/Getty Images

By Elizabeth Dias and Ruth Graham

Dec. 31, 2022

The death of Pope Benedict XVI Saturday sent a broad wave of mourning through the American church. At the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, a single bell tolled for 15 minutes at the Basilica of the Sacred Heart.

But his death held special meaning for the conservative wing of American Catholicism: It represented the loss of their unofficial figurehead, a shadow presence whose influence they followed even after he resigned in 2013 and Pope Francis became the church’s global leader.

While he largely faded from public life since his unexpected retirement, the former pope — whose early reputation as a firebrand once earned him the nickname “God’s Rottweiler” — remained a hero to many theological conservatives, who viewed him as a standard-bearer for a kind of doctrinal commitment and rigor they saw lacking in the church under Francis.

In recent years, the conservative wing of American church leadership has been gaining power, and has clashed openly and often with the country’s second Catholic president, Joseph R. Biden Jr., and the speaker of the House of Representatives, Nancy Pelosi, over the issue of abortion.

On Saturday, during a vacation in St. Croix, Mr. Biden released a statement that said he and his wife “join Catholics around the world, and so many others, in mourning the passing of Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI,” adding that the pope “will be remembered as a renowned theologian, with a lifetime of devotion to the church, guided by his principles and faith.”

Mr. Biden remembered Benedict’s comments during a 2008 visit to the United States and White House, where the pope noted that the “need for global solidarity is as urgent as ever, if all people are to live in a way worthy of their dignity.”

Ms. Pelosi, a Democrat of California who is also Catholic, expressed her admiration of Benedict’s spirituality and recalled welcoming the pope to Washington in 2008 and visiting him at the Vatican the next year.

“Paul and I join our fellow Catholics in mourning the passing of Pope Benedict XVI: a global leader whose devotion, scholarship and hopeful message stirred the hearts of people of all faiths,” she wrote in the statement, referring to her husband.

Benedict’s promotion of Catholic leaders, including Cardinal Timothy M. Dolan of New York, helped shape the character of church hierarchy in the United States at its highest levels. Parts of the American church, including the younger generation of priests, have long held Benedict “in an awe bordering on reverence,” said George Weigel, a conservative Catholic commentator and author of “To Sanctify the World: The Vital Legacy of Vatican II.”

Catholics make up about 20 percent of all U.S. adults. The church has grown increasingly polarized in the past few years, and the faction that has opposed Pope Francis’ agenda has strengthened.

At their annual meeting in November, U.S. bishops chose as their top leaders Archbishop Timothy P. Broglio, who was named by Benedict to the Archdiocese for the Military Services, and Archbishop William E. Lori of Baltimore, who was elevated to his role by Benedict. Both have prioritized an opposition to abortion and have taken conservative stances on an array of social issues.

Benedict “continued throughout his long life to be an effective teacher of the faith,” Archbishop Broglio said in a statement. “It will take many years for us to delve more deeply into the wealth of learning that he has left us.”

Benedict’s theological writings and influence as Joseph Ratzinger, when he was Pope John Paul II’s right-hand man, made him one of the most dominant forces to shape the culture of the current American priesthood.

No one was more important in helping John Paul II turn the church to the right, said David Gibson, director of the Center on Religion and Culture at Fordham University.

“It continued to shift to the right more than I think he would have liked or envisioned,” Mr. Gibson said. “The orthodoxy he envisioned morphed into a kind of Tea Party Catholicism that may have been as strange to him as any liberal developments in the ’60s and ’70s.”

When Benedict visited the United States in 2008, he warned against the “subtle influence of secularism” that could lead Catholics to accept abortion, divorce and cohabitation outside of marriage.

He also acknowledged the “deep shame” caused by the sexual abuse scandal and said it was “sometimes very badly handled” by the church.

Benedict’s resignation, heralded by some as a move of humility, was also seen by his critics as fallout from the church’s mishandling of that crisis.

For many survivors of sexual abuse, his theological intellect could not compensate for his limited response to the global crisis, either when he led the church’s top doctrinal watchdog or as pope.

“Had he disciplined complicit bishops like he disciplined dissident theologians, a lot of cover-ups and crimes would have been stopped,” said David Clohessy, the former national director of SNAP, the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests.

“He was brilliant but timid, causing thousands of children to be assaulted by refusing to act decisively to end decades of irresponsible church secrecy around child sex crimes,” he said.

In the United States, Benedict’s legacy is in the intellectual tradition and hierarchical appointments he leaves behind. His high-profile promotions include Cardinal Sean P. O’Malley of Boston, Cardinal Donald Wuerl, formerly of Washington, and Cardinal Raymond L. Burke, the former archbishop of St. Louis.

Cardinals around the country released statements of tribute and mourning.

“His life and his pontificate were based in a deep and abiding faith and an extraordinary record of theological scholarship,” Cardinal O’Malley said. “In all of my personal interactions with Pope Benedict XVI, I found him to be an engaged leader, thoughtful in his decisions and always committed to the mission of the Church.”

He added, simply: “I will miss Pope Benedict.”

Cardinal Dolan called on every parish in the archdiocese of New York to offer a Mass “for the Good Lord’s mercy upon his gracious soul, and in thanksgiving for his vocation as Successor of St. Peter. May the angels lead him into paradise!”

As a young priest and theologian in the 1960s, Benedict attended the Second Vatican Council, where he was perceived as a relative liberal at a time of dramatic change to the church’s liturgy, rituals and approach to the secular world. He later became alarmed by what he perceived as a leftward theological drift in the church, though he said that his theological positions did not change.

“You might say this is the definitive drawing down of the curtain on Vatican II,” said Bishop Robert Barron of the Diocese of Winona-Rochester in Minnesota, and the influential founder of the Catholic media organization Word on Fire.

The fact that Benedict’s post-papacy lasted almost a decade surprised many observers, Bishop Barron said, describing Benedict as a fundamentally introverted intellectual. “The way he lived the last 10 years was probably the way he wanted to live his life,” he said.

Benedict’s retirement, unprecedented in the modern era, was a bombshell that has softened with time. “For a lot of Catholics, he might be a pretty distant figure,” Bishop Barron said.

For others, the loss is that of an intellectual giant and beloved pastoral figure.

Helen Alvaré, an associate dean at Antonin Scalia Law School at George Mason University, has been studying Benedict’s work since the 1980s.

Just this week, she said, she was reading from “Truth and Tolerance,” a compilation of the former Joseph Ratzinger’s lectures on Catholic teachings in the context of contemporary global religion.

Benedict was “the continuity between Vatican II and today,” she said, describing him as an “encyclopedia” of church history.

“We feel like we’re losing a grandfather,” she said.

Jim Tankersley contributed reporting from Saint Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands, and Stephanie Lai from Washington D.C.

Elizabeth Dias covers faith and politics from Washington. She previously covered a similar beat for Time magazine. @elizabethjdias

Ruth Graham is a Dallas-based national correspondent covering religion, faith and values. She previously reported on religion for Slate. @publicroad

Opinion

Benedict was America’s pope

By David Von Drehle

For more than a century, from the time when Ireland’s potato crop failed and starvation sped a great migration of Irish to the United States, nativists feared the influence of Roman Catholicism over American life. Anti-Catholic sentiment helped fuel the Know Nothing movement of the 1840s and 1850s. The prejudice poisoned the 1884 presidential campaign with charges of “rum, Romanism, and rebellion” against the Democratic Party. It marched alongside racism in Ku Klux Klan parades of the 1920s and doomed Democrat Alfred E. Smith’s presidential bid in 1928. John F. Kennedy’s narrow victory in 1960 was thought to be a stake through the heart of hatred.

Ironically, the influence ran in the opposite direction. Popes had relatively little impact on the formation of American morals and culture compared with the enormous changes wrought on the Vatican by U.S. modernizing power. Pope John XXIII’s historic decision to call the Second Vatican Council to begin gathering in 1962 was, in many senses, a recognition that the Catholic Church must engage with the free and individualistic world that the postwar United States was making.

Two priests who served as theological experts at Vatican II would go on to alter that dynamic and to bring Roman Catholicism to a place of prominence in American life unmatched throughout our history. One, from Poland, was Karol Wojtyla, then an auxiliary bishop of Krakow, now Pope Saint John Paul II. The other, a brilliant young professor from the University of Bonn, was Joseph Ratzinger, who would serve John Paul II as chief keeper of the faith and succeed him as Pope Benedict XVI.

With Benedict’s death at 95 on Saturday in Rome, the shared work of these two men can be read in American Catholicism’s dramatic shift toward the cultural right. From John Paul’s election to the papacy in 1978 to Benedict’s unusual resignation from office in 2013, every bishop consecrated in the United States (and worldwide) was approved by one of these two, and every professor licensed to teach Catholic theology according to church doctrine was subject to their potential review.

Their view of Vatican II was not the one that prevailed in the United States immediately after the council adjourned in 1965. Most observers expected that engagement with the modern world would liberalize Catholicism and lead quickly to new policies on birth control, abortion, marriage for priests and so on.

John Paul’s strong anti-communist activism in Poland, along with his movie-star looks and approachable smile, led many Americans to mistakenly believe he would align the church with modern Western culture. But they had not read his theological work, especially the series of meditations that elevated him to eminence in Rome and were published as “A Sign of Contradiction.”

Written for a 1976 retreat called by Pope Paul VI for the Roman Curia, these essays explained John Paul’s view that post-Vatican II engagement with modernity was not meant to change the church so much as it was meant to change the modern world. Catholicism would stand in contradiction to liberal trends in society, offering its unchanging doctrines as an alternative to a world evolving for the worse.

John Paul took his smile on the road, traveling the globe as no pontiff had ever done before. He appointed Ratzinger, then an archbishop and cardinal, prefect of the powerful Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith — the old Inquisition — and there he served as the hammer within the velvet glove, purging liberal theologians, clipping the wings of left-leaning bishops and elevating cultural conservatives to positions of power.

E.J. Dionne: Pope Benedict’s legacy is one of paradox

Their work continued after John Paul’s death in 2005 as Ratzinger became Pope Benedict XVI and kept up the countercultural momentum. Storms of scandal over priestly sex abuse prompted some thinkers to ask if the ideal of celibate male leaders in the church had fostered a culture of lies. But for Benedict and his like-minded churchmen, modern promiscuity was to blame. Their solution: tighter screening of seminarians for mental health and orthodox commitment.

The defining engagement in American politics has been over the issue of abortion. As John Paul’s hammer, Ratzinger taught that “not all moral issues have the same moral weight as abortion.” Under his influence, opposition to abortion became a defining aspect of Catholic identity here: Catholic schools bus students to protest rallies. Catholic hospitals refuse to offer certain medical procedures. Catholic churches raise money to fund antiabortion campaigns.

On June 24, the U.S. Supreme Court contradicted nearly 50 years of its own jurisprudence by holding that the Constitution does not protect a woman’s right to choose an abortion. Five of the six justices who voted to overturn Roe v. Wade are conservative Roman Catholics. (The sixth was a graduate student under a leading expert in Catholic legal philosophy.)

Catholic leaders hailed the decision — which might never have happened without the ministry of Pope Benedict XVI.

Opinion by David Von DrehleDavid Von Drehle is a deputy opinion editor for The Post and writes a weekly column. He was previously an editor-at-large for Time Magazine, and is the author of four books, including “Rise to Greatness: Abraham Lincoln and America’s Most Perilous Year” and “Triangle: The Fire That Changed America.” Twitter

Pope Benedict's mixed legacy: A poor administrator who made theological contributions

OPINION

NCR VOICES

Pope Benedict XVI leads his last public Angelus from the window of his apartment overlooking St. Peter's Square at the Vatican Feb. 24, 2013. He resigned the papacy four days later, the first to do so voluntarily in more than 700 years. (CNS/Vatican Media)

BY MICHAEL SEAN WINTERS

View Author Profile

It is a strange quality of Pope Benedict XVI's pontificate that he will be known to history first and foremost for the means by which he exited his office, a voluntary resignation, something not seen in centuries. That resignation was a great act of demystification, a recognition that the papacy was an office, a very special office to be sure, but an office nonetheless. It was also an implicit, unspoken rebuke to John Paul II's contrary decision to hold on to office despite the incapacities of old age.

The day Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger was elected pope, April 19, 2005, a bishop who knew him observed, "Remember, Benedict the pope is not the same thing as Ratzinger the cardinal." This enigmatic comment turned out to be profoundly true, and true in ways that highlighted the successes and the failures of the papacy that followed.

At its simplest, the observation was a recognition that being prefect for the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith had been a desk job, and until he was elected pope, we never saw pictures of Ratzinger with children or in any pastoral setting. At its most complex, it was a recognition that Ratzinger's relationship to the entire life of the church, including to theology, was transformed by his election as pope.

And, so, the man who had been entrusted with the delicate task of removing those who sexually abused minors from the clergy, and had spent years reading dossiers that would sicken any decent person, was finally able to move against those whom John Paul II had protected, serial abusers like Fr. Marcial Maciel, founder of the Legionaries of Christ. The idea of holding accountable bishops who covered up abuse, however, was a bridge too far for the German pontiff, so his legacy on the issue of clergy sex abuse is decidedly mixed, better than that of his predecessor, but still inadequate.

As prefect at the CDF, Ratzinger had been instrumental in silencing theologians who failed to meet his standards of orthodoxy. As pope, he was more forgiving. Soon after his election, he hosted Swiss theologian Fr. Hans Küng, whose license to teach Catholic theology had been revoked by the Vatican with Ratzinger's acquiescence, at Castel Gandolfo where the two old colleagues and rivals had a four-hour meeting, including dinner, that the Vatican described as "friendly." Küng told NCR after the meeting: "It's clear that we have different positions. But the things we have in common are more fundamental. We are both Christians, both priests in service of the church, and we have great personal respect for one another."

Italian Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone kisses the ring of Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI as he arrives for a consistory led by Pope Francis in St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican Feb. 22, 2014. At right is Cardinal Angelo Sodano. It was Pope Benedict's first public appearance at a liturgy since his retirement a year earlier. (CNS/Paul Haring)

Arguably, the most important quality in an effective pope is judgment of character, and specifically the ability to get the right person in the right job. Here, Benedict's legacy was uneven. In selecting San Francisco Archbishop William Levada to succeed him as prefect at the CDF, Benedict found someone exceedingly capable and not the least overwhelmed by the enormity of having to report weekly to the person who had held the post for 25 years. On the other hand, Benedict's loyalty to Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone, his secretary of state, was entirely misplaced, as Bertone was engulfed in both the leaks scandal and questions about his misuse of funds.

The most egregious example of Benedict failing to recognize the inadequacy of certain traditional methods for the managerial needs of a modern papacy was his appointment of Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò as nuncio to the United States. This was a classic case of "promote to remove," in which Viganò's enemies got him transferred to Washington after he caused a stir alleging malfeasance in the governance of the Vatican City State. Viganò implored Benedict to let him stay in Rome, made clear his intense dislike for the United States, but Benedict moved him anyway. It was a disastrous decision.

The damage Viganò did in the U.S. church is incalculable. Any nuncio is going to get about half his nominations for episcopal appointments through, and Viganò's list includes the appointments of Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone to San Francisco; Bishop Michael Barber to Oakland; Bishop Michael Olson to Fort Worth, Texas; Archbishop Alexander Sample to Portland, Oregon; Bishop Thomas Daly to Spokane, Washington; and Bishop Joseph Strickland to Tyler, Texas. Each appointment reflects a backward vision of the Catholic Church, in which a supposed Golden Age before Vatican II is to be aped. Buskins and birettas are dusted off, priests face the wall, tabernacles are put back behind the altar of sacrifice, the world is kept at a distance, and any engagement with modernity is done from a defensive crouch.

Pope Benedict XVI greets youths at the Missionaries of Charity Peace and Joy Center in Cotonou, Benin, Nov. 19, 2011. (CNS/Paul Haring)

These lousy personnel decisions were accompanied by some terrible administrative ones. Benedict's 2007 decision to liberalize access to the Tridentine rite with the motu proprio Summorum Pontificum backfired badly, based on a reflexive tendency to assume the best about conservative Catholics. "He never intended to start a movement," one of his collaborators told me a few years after the decision. It was worse than that. The decision launched an ideology, one that increasingly denied the legitimacy of the Second Vatican Council.

Similarly, his 2012 decision to investigate the Leadership Conference of Women Religious displayed a reflexive tendency to believe the worst about the Catholic left. The humiliation of women who had given their lives to the church, proclaiming the Gospel by their work in education and health care and other ministries, was boneheaded, even if the result was not as bad as some people feared.

It is in the area of theology, however, that Joseph Ratzinger made his most significant contributions. His 1966 book Introduction to Christianity remains, like Küng's On Being a Christian, the kind of accessible theological work you can hand to a smart teenager or college student to help them grasp what being Catholic is all about — much better than giving them a copy of the catechism. His trilogy Jesus of Nazareth, published while he was pope, similarly offers B+ Catholics a series of reflections on the person of Jesus Christ that is both provocative and undoubtedly orthodox. Some curial officials complained that popes need to govern the church, not write books, and it would have been better for the church if Benedict had first hired someone more competent than Bertone to run the show, but these books will endure.

As CDF prefect, Ratzinger's fundamental problem was to mistake a theoretical issue for a practical or pastoral one. His concern about the "dictatorship of relativism" was not wrong, but he spoke about it as an intellectual challenge, which it is, but failed to see the ways participation in the consumerist, market economy was the real pastoral incubator for relativism. Similarly, his criticisms of liberation theology were well-founded — the theological anthropology really was lacking in some of the works criticized by the CDF — but those concerns were not advanced by the clumsy method of public condemnation.

As pope, Benedict made two enduring contributions to theology. His 2005 encyclical, Deus caritas est, continued the Christological focus that was a hallmark of Vatican II. Indeed, this last pope to have attended Vatican II always insisted, and rightly, on the primary focus on the person of Christ as the touchstone of Vatican II's soteriological, ecclesiological and anthropological teachings.

His 2009 encyclical, Caritas in veritate, building on the Christology of his prior work, insisted on the need to integrate notions of grace and gratuitousness into our Catholic social teaching, a profound challenge to modern economic and political assumptions. In this regard, it was more radical, and more compelling, than any work produced by a liberation theologian. The church is still only beginning to wrestle with the implications of this insight from Pope Benedict, and it is impossible to see how we will ever embrace Pope Francis' call to ecological stewardship without first more deeply receiving this teaching on grace and gratuitousness from his predecessor.

Pope Benedict XVI walks through the gate of Auschwitz, the former Nazi death camp in Poland, in this May 28, 2006, file photo. His visit to Poland paid tribute to his predecessor, Pope John Paul II. (CNS/Reuters/Pawel Kopczynski)

A final note. Like John Paul II, Pope Benedict's commitment to combating antisemitism was remarkable. To have a pope born within miles of Auschwitz, followed by one born in Hitler's Germany, both visit concentration camps to denounce the scourge of antisemitism, to visit with Jewish leaders when they made pastoral visits, to encourage Catholic-Jewish and Catholic-Muslim dialogues, to go to Jerusalem — these were fruits of the council. Any one of these acts were unimaginable in the church of Pius IX or Fr. Charles Coughlin. That all of them came to pass in the late 20th and early 21st centuries is astounding.

Pope Benedict's legacy, then, is a mixed one. A shy man thrust into the limelight, he proved unequal to some of the administrative challenges of running a universal church even while many of his theological contributions will endure. He made mistakes, some of them large ones, but his integrity was beyond reproach. In retirement, Benedict was demonstrably loyal to Pope Francis, and if his loudest champions in the U.S, had followed his example, the Catholic Church in this country would be far less polarized.

Mostly, Pope Benedict will be remembered as a profoundly intelligent and prayerful man, called to leadership during a time of turmoil in a church, who was not really suited for such rough waters. Through those waters, he steered the barque of Peter faithfully, if not always successfully.

This story appears in the The Ratzinger/Benedict XVI legacy feature series.