Questions about if, when and how to use lethal autonomous weapons are no longer limited to warfare.

Branka Marijan

January 2, 2023

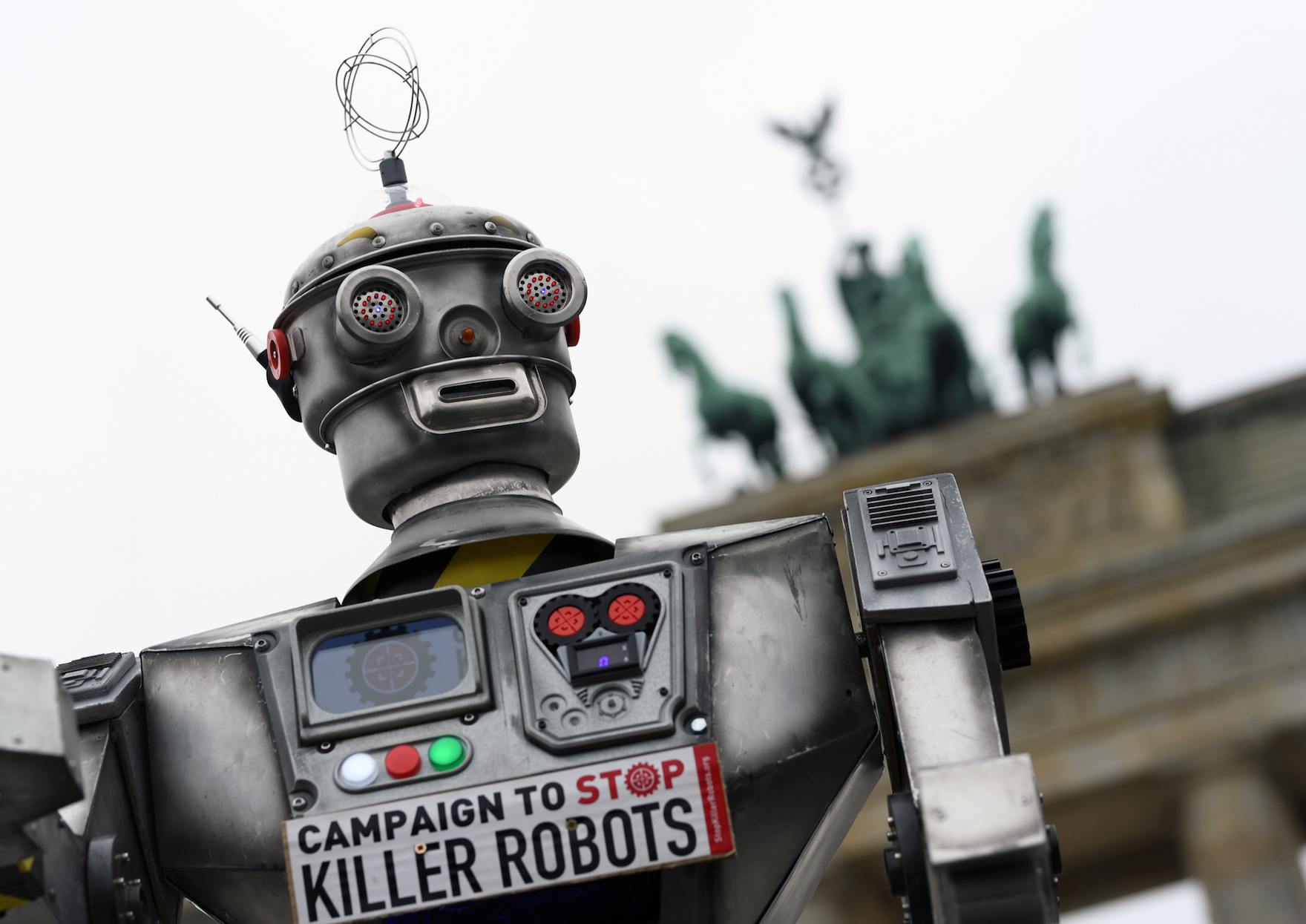

The headline-making vote by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors on November 29 to allow police to use robots to kill people in limited circumstances highlights that the questions of if, when and how to use lethal autonomous weapons systems — a.k.a. “killer robots” powered by artificial intelligence (AI) — are no longer just about the use of robots in warfare. Moreover, San Francisco is not the only municipality wrestling with these questions; the debate will only heat up as new technologies develop. As such, it is urgent that national governments develop policies for domestic law enforcement’s use of remote-controlled and AI-enabled robots and systems.

One week later, San Francisco law makers reversed themselves, after a public outcry, to ban the use of killer robots by the police. Nonetheless, their initial approval crystallized the concerns long held by those who advocate for an international ban on autonomous weapons: namely, that robots that can kill might be put to use not only by militaries in armed conflicts but also by law enforcement and border agencies in peacetime.

Indeed, robots have already been used by police to kill. In an apparent first, in 2016, the Dallas police used the Remotec F5A bomb disposal robot to kill Micah Xavier Johnson, a former US Army reservist, who fatally shot five police officers and wounded seven others. The robot delivered the plastic explosive C4 to an area where the shooter was hiding, ultimately killing him. Police use of robots has grown in less dramatic ways as well, as robots are deployed for varied purposes, such as handing out speeding tickets or surveillance.

So far, the use of robots by police, including the proposed use by the San Francisco police, is through remote operation and thus under human control. Some robots, such as Xavier, the autonomous wheeled vehicle used in Singapore, are primarily used for surveillance, but nevertheless use “deep convolutional neural networks and software logics” to process images of infractions.

Police departments elsewhere around the world have also been acquiring drones. In the United States alone, some 1,172 police departments are now using drones. Given rapid advances in AI, it’s likely that more of these systems will have greater autonomous capabilities and be used to provide faster analysis in crisis situations.

While most of these robots are unarmed, many can be weaponized. Axon, the maker of the Taser electroshock weapon, proposed equipping drones with Tasers and cameras. The company ultimately decided to reverse itself but not before the majority of its AI Ethics board resigned in protest. In the industry, approaches vary. Boston Dynamics recently published an open letter stating it will not weaponize its robots. Other manufacturers, such as Ghost Robotics, allow customers to mount guns on their machines.

Even companies opposed to the weaponization of their robots and systems can only do so much. It’s ultimately up to policy makers at the national and international levels to try to prevent the most egregious weaponization. As advancements in AI accelerate and more autonomous capabilities emerge, the need for this policy will become even more pressing.

The appeal of using robots for policing and warfare is obvious: robots can be used for repetitive or dangerous tasks. Defending the police use of killer robots, Rich Lowry, editor-in-chief of National Review and a contributing writer with Politico Magazine, posits that critics have been influenced by dystopic sci-fi scenarios and are all too willing to send others into harm’s way.

This argument echoes one heard in international fora on this question, which is that such systems could save soldiers’ and even civilians’ lives. But what Lowry and other proponents of lethal robots overlook are the wider impacts on particular communities, such as racialized ones, and developing countries. Avoiding the slippery slope of escalation when allowing the technology in certain circumstances is a crucial challenge.

The net result is that already over-policed communities, such as Black and Brown ones, face the prospect of being further surveilled by robotic systems. Saving police officers’ lives is important, to be sure. But is the deployment of killer robots the only way to reduce the risks faced by front-line officers? What about the risks of accidents and errors? And there’s the fundamental question of whether we want to live in societies with swarms of drones patrolling our streets.

Police departments are currently discussing the uses of killer robots in extreme circumstances only. But as we have seen in past uses of technology for policing, use scenarios will not be constrained for long. Indeed, small infractions and protests have in the past led to police using technology originally developed for battlefields. Consider, for example, the use of the Predator B drone, known as the Reaper, to surveil protests in Minneapolis, Minnesota by the U.S. Customs and Border Protection Agency. While these drones are unarmed, their use in an American city, in response to protests against racially motivated policing, was jarring.

Technological advancements may well have their place in policing. But killer robots are not the answer. They would take us down a dystopian path that most citizens of democracies would much rather avoid. That is not science fiction, but rather the reality - if governance does keep pace with technological advancement.

A version of this article appeared in Newsweek.

The opinions expressed in this article/multimedia are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of CIGI or its Board of Directors.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Branka Marijan

Branka Marijan is a senior researcher at Project Ploughshares, where she leads research on the military and security implication of emerging technologies.

Bessma MomaniAaron ShullJean-François BélangerRebecca CrootofBranka MarijanEleonore PauwelsJames RogersFrank SauerToby WalshAlex Wilner

November 28, 2022

The most complex international governance challenges surrounding artificial intelligence (AI) today involve its defence and security applications — from killer swarms of drones to the computer-assisted enhancement of military command-and-control processes. The contributions to this essay series emerged from discussions at a webinar series exploring the ethics of AI and automated warfare hosted by the University of Waterloo’s AI Institute.

Introduction: The Ethics of Automated Warfare and AI

Bessma Momani, Aaron Shull, Jean-François Bélanger

AI and the Future of Deterrence: Promises and Pitfalls

Alex Wilner

The Third Drone Age: Visions Out to 2040

James Rogers

Civilian Data in Cyberconflict: Legal and Geostrategic Considerations

Eleonore Pauwels

AI and the Actual IHL Accountability Gap

Rebecca Crootof

Autonomous Weapons: The False Promise of Civilian Protection

Branka Marijan

Autonomy in Weapons Systems and the Struggle for Regulation

Frank Sauer

The Problem with Artificial (General) Intelligence in Warfare

Toby Walsh

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Bessma Momani

CIGI Senior Fellow Bessma Momani has a Ph.D. in political science with a focus on international political economy and is full professor and assistant vice‑president, research and international at the University of Waterloo.

Aaron Shull

Aaron Shull is the managing director and general counsel at CIGI. He is a senior legal executive and is recognized as a leading expert on complex issues at the intersection of public policy, emerging technology, cybersecurity, privacy and data protection.

Jean-François Bélanger

Jean-François Bélanger is a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Political Science at the University of Waterloo working with Bessma Momani on questions of cybersecurity and populism.

Rebecca Crootof

Rebecca Crootof is an associate professor of law at the University of Richmond School of Law. Her primary areas of research include technology law, international law and torts.

Branka Marijan

Branka Marijan is a senior researcher at Project Ploughshares, where she leads research on the military and security implication of emerging technologies.

Eleonore Pauwels

Eleonore Pauwels is an international expert in the security, societal and governance implications generated by the convergence of artificial intelligence with other dual-use technologies, including cybersecurity, genomics and neurotechnologies.

James Rogers

James Rogers is the DIAS Associate Professor in War Studies within the Center for War Studies at the University of Southern Denmark, a non-resident senior fellow within the Cornell Tech Policy Lab at Cornell University and an associate fellow at LSE IDEAS within the London School of Economics.

Frank Sauer

Frank Sauer is the head of research at the Metis Institute for Strategy and Foresight and a senior research fellow at the Bundeswehr University in Munich.

Toby Walsh

Toby Walsh is an Australian Research Council laureate fellow and scientia professor of artificial intelligence at the University of New South Wales.

Alex Wilner

Alex Wilner is an associate professor at the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs, Carleton University, and the director of the Infrastructure Protection and International Security program.

:quality(100)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thesummit/I55MMFEBYZESDGQM7I6OMPNIUM.jpg)

:quality(100)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/thesummit/1b9c2687-61a3-46be-ad63-bf958ee49a64.png)

:quality(100)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/thesummit/e8f2b2b2-0a78-435f-b601-d73594af3b04.jpg)

:quality(100)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thesummit/7CDLUGFWRJE4ZLKI2ZRI7KU7DQ.jpg)

:quality(100)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/thesummit/d58de53e-d53e-4183-8967-a2caccf17cfa.jpg)