Reservation Dogs: Strange diseases are spreading in Blackfeet Country. Can canines track down the culprits?

Sully is a black-haired border collie and retriever mutt. Grist / Zoya Teirstein

- BY ZOYA TEIRSTEIN, GIST

LONG READ

The sun is setting in Glacier County, Montana. Souta Calling Last guns her diesel-powered white GMC pickup truck east on Highway 2.

The car following her can barely keep up as she hurtles across the dimming prairie, one hand resting lightly on the steering wheel, her eyes scanning the side of the highway. Calling Last, a researcher and an enrolled member of the Blood Tribe — one of the four nations that make up the Blackfoot Confederacy — grew up on the Blackfeet reservation. She knows this landscape by heart.

Editors Note: This story was originally published by Grist. You can subscribe to its weekly newsletter here. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

“There it is,” she says and yanks the steering wheel to the right, sending a plume of dust into the air as she brakes hard on the gravel shoulder. The Two Medicine River, sacred to the Amskapi Pikuni, the Blackfeet, rushes nearby. A couple of minutes later, a gray Toyota slowly pulls in behind the GMC and rolls to a stop. The words “Working Dogs for Conservation” are printed on its side in block letters. A volley of excited yips and whines rings out from the truck bed.

Calling Last has brought Working Dogs for Conservation, or WD4C, a nonprofit that trains dogs to hunt down invasive species and poachers, to the Blackfeet reservation to help her solve a mystery. In recent decades, unusual cancers and thyroid issues have bloomed in clusters across the Nation. Some Blackfeet stopped harvesting wild plants and animals — like mint, huckleberries, and elk — suspecting that traditional sources of sustenance for countless generations had become contaminated and diseased. But so far, there’s been limited empirical research linking the tribe’s public health woes to its environment. Calling Last aims to change that by conducting a comprehensive scientific survey of environmental contaminants in Blackfeet territory. If it works, her experiment will give the community peace of mind and the freedom to harvest wild edibles safely.

Her success relies on two restless dogs waiting in crates in the back of the gray truck.

Frost is a rust-and-cream-colored Springer spaniel-pit mix, Sully is a black-haired border collie and retriever mutt. Sully, who was trained to track down human remains before he came to WD4C, was part of an unplanned litter. Frost was surrendered by his former owners for being too excitable, too energetic, and too obsessed with balls — traits that made him a perfect candidate for professional service.

Freed from the back of the truck, Frost and Sully zigzag from bank to bank, their tails wagging furiously. They’ve been trained to pinpoint mink and otter droppings, or scat, which can contain toxins because of processes called bioaccumulation and biomagnification, when substances move through the food chain and get concentrated in organisms. Insects like mayflies and dragonflies pick up toxins from their environment and accumulate them in their exoskeletons, then they’re consumed in vast numbers by trout and other fish, which in turn get eaten by mink and otters. The mammals leave their scat, infused with whatever toxins were originally in the insects, on the sides of the Two Medicine and other water bodies on the reservation.

All of a sudden, Frost stops running and starts sniffing around a beaver dam. Michele Vasquez, a canine field specialist who is leading the Blackfeet project for WD4C, isn’t sure whether the dog is excited about scat or if he’s trying to rouse an animal hiding in the dam, but she hangs back a few feet to let him work. Seconds later, Frost sits and makes eye contact with Vasquez. “Yeah? You think you’ve got something?” she asks him, and leans forward for a closer look.

Sure enough, a small, jet black dropping is perched precariously on a twig a few inches inside the beaver dam: mink scat. “What a guy!” Vasquez exclaims. She pulls Frost’s reward, a yellow ball on a rope, out of her fanny pack and chucks it into the river. Frost dives after it, ecstatic. Vasquez’s colleague, forensic field specialist Ngaio Richards, walks over and dons a plastic glove before reaching her hand into the dam to collect the sample and put it in a paper bag. Vasquez marks the place where Frost found the scat on her GPS. They’ll send the scat, and all the other samples they collect on this trip, to a lab for testing. When the results come back, Calling Last will share the data with her community. Clean scat means it’s safe to harvest wild edibles from this part of the river; toxic scat means it’s better to harvest somewhere else.

Calling Last has heard stories about contaminants buried on the reservation her whole life: whispers about a web of toxic hotspots, the legacy of decades of illegal dumping of trash, electronics, and other hazards. Rumors that a company paid the tribe a paltry sum to bury a cache of nuclear waste somewhere on the Nation’s rolling plains in the 1960s. Snatches of information about the chemicals companies used for fracking in the Bakken shale formation, which runs beneath part of the reservation and contains billions of barrels of oil and natural gas. The threat of oil extraction still looms today. The tribe is currently fighting to stop an oil company, Solenex, that wants to drill near the Badger and Two Medicine Rivers, which hold some of the tribe’s most sacred and culturally significant sites.

These scattered reports have contributed to a sense of unease among the Nation. “I feel like there’s a lot of fear on the reservation,” Celina Gray, a Little Shell and Blackfeet mother of four and a graduate student at the University of Montana studying wildlife biology, said. She wants to take her kids out hunting and foraging with her, but she doesn’t want to expose them to the environmental health hazards she suspects are lurking in the soil.

Rates of cancer are higher on the Blackfeet Nation than elsewhere in Montana. Six in 1,000 Blackfeet were diagnosed with some type of cancer, on average, every year between 2005 and 2014, compared to 5 in 1,000 Montanans per year over the same period. An assessment of health risks among Blackfeet shows cancer was the leading cause of death on the reservation between 2014 and 2015 — 16 percent of overall deaths during that time period. But the tribe lacks the data it needs to get a fuller sense of how the disease is impacting Blackfeet and what could be causing these higher rates.

Calling Last says it’s not just the higher rate of cancer that concerns her, but the way the disease and its warning signs appear, in clusters, that makes her think people may be exposed to unknown health risks from the environment.

Kim Paul, the founder of a public health nonprofit called the Piikani Health Lodge Institute, tried to track down the source of the cancer when she was a graduate student at the University of Montana in the 2010s. Because she’s a member of the community, she knew about a 10-mile-long portion of the reservation, 40 miles north of the Blackfeet headquarters in the town of Browning, where every family but one had developed multiple forms of cancer. She remembered her grandmother’s warnings, when Paul was just a little girl, not to collect bear grass or flowers from that part of the reservation. “There was a lot of death in that stretch of road,” Paul said. At the University of Montana, she started collecting samples from the area to conduct a study, but quickly ran out of money and was forced to abandon the project.

Now, Calling Last is picking up the mantle. She was awarded a grant from the Environmental Protection Agency to devise a project that will establish a database of environmental stressors at sites across the reservation that are both important harvesting spots and hold cultural significance to the Nation. Calling Last expects to find trace amounts of uranium and other nuclear energy byproducts, heavy metals that leached from illegal and legal dumpsites, pharmaceutical residue flushed or tossed by members of the tribe, and flame retardants and other pollutants carried into waterways by urban runoff. Then, she’ll add that data to a virtual map she’s making for her community.

When it’s complete, her map will have more than 30 layers — sites of cultural importance, traditional names for rivers and valleys, toxic dumps, areas where it is dangerous to harvest plants and animals, and more. Each layer will serve a different role in achieving an overarching goal: to help the Blackfeet protect their health, preserve their traditional ways of life, and strengthen their hold on cultural identity and knowledge.

But first, Calling Last needs to find mink and otter scat. Or rather, the dogs do.

Frost and Sully get food and love from their trainers. They affectionately call Frost “melon butt,” because of the dense bunches of muscles at the top of his stocky legs. And in return, WD4C gets access to the dogs’ secret weapons: their noses.

Humans can see well and we have big brains, but we don’t have very many scent receptors in our nostrils — at least, not compared to dogs. All of the scent receptors from a human’s nose, laid side by side, would fit on the surface of a postage stamp. All the scent receptors from a dog’s snout would fill a handkerchief. “Let’s say you walk into a house and you smell spaghetti dinner being cooked,” Hugh Murray, a K-9 handler for the Quapaw Nation of Oklahoma. “You smell the product. They smell the individual ingredients, the flour, the sugar, the tomato. They break things down individually.”

A dog can also pinpoint a single ingredient in a forest of other smells, a “single drop of perfume in an Olympic size pool,” Amanda Ott, a dog trainer for Working Dogs for Conservation, said, which is what makes them so good at working in the field.

Dogs have been trained to sniff out cancer, bed bugs, COVID-19, even stress. But canine fieldwork has drawbacks, and each working dog has its own idiosyncrasies. Ott, who owns and trains the black lab mix Sully, recently lost him briefly when a moose took after the pup.

And switching dogs from one project to another can confuse them as well. Frost, who had just come back to Montana after three weeks in Wyoming hunting down invasive plant species, would occasionally get sidetracked by a plant that looked like a target from his previous adventure while looking for scat along the Two Medicine River. With gentle coaxing from Vasquez, though, he was able to refocus.

Over the course of nine days of surveying, the two dogs found more than 70 scat samples. On their last day of work on the reservation, a member of the community told Calling Last that someone had illegally dumped barrels of used motor oil into the water upriver from one of her testing sites. Vasquez said the silver lining is that now the researchers will have data from before and after the incident. “So lies the crux of this work,” she said.

Eight years ago, Calling Last would never have imagined designing research around the vagaries of dogs. She was working as a water training facilitator, teaching Indigenous and non-Indigenous water operators how to manage their systems. She infused her trainings with presentations on the cultural importance of water and the original names for rivers and streams. “I tried to implant in them that they are our communities’ modern day water warriors, because they’re cleaning the water,” she said.

But the work wasn’t fulfilling. She quit her job and set about starting her own organization. After a year, she had cashed in her 401(k) and savings accounts, maxed out her credit cards, and succeeded in forming the group she still runs as a one-woman show today: Indigenous Vision. She holds cultural sensitivity trainings for Native and non-Native groups, runs educational programs for Blackfeet youth, and has spent the past several years building out the multi-layered map.

Calling Last laid out the stakes for me as she drove between surveying spots, pausing once in a while to take swigs of an energy drink and sing along to the mid-2000s hits thumping from a playlist on her phone. Blackfeet Nation is where she was raised, and where much of her family and many of her friends live. She grew up picking mint, sage, and sweetgrass on the reservation’s prairies. Her relatives hunt for buffalo, deer, and elk in its mountains and plains.

Hunting and foraging are not only crucial aspects of Blackfeet spiritual and cultural identity, she said, they’re a means of survival for a community that lacks critical resources. Some 36 percent of people on the reservation live below the poverty line, compared to 12.5 percent statewide. More than two-thirds of all Blackfeet are food insecure, meaning they don’t have reliable access to nutritious food. Wild animals and plants are cheaper, healthier, and fresher than the meat and produce available at the grocery store, Celina Gray, the graduate student, said. “The meat we ate all winter long was elk burger,” she said, “I don’t buy hamburger at Costco.”

But Blackfeet will only continue turning to those traditional methods of harvesting as long as they can trust them. Calling Last has watched as, over the years, her friends, family, and wider community developed unusual health problems — and she hasn’t been spared, either.

“Me, a bunch of other people, my mom, all the women in my family, have thyroid issues,” she said. To her, the source of the sickness is clear: “It’s gotta be something from our environment.”

That’s why Calling Last, who has a degree in water management from the University of Montana, has dedicated her life to building this map. “As a scientist, I can read Excel sheets and see data trends just by looking at the numbers,” she said. “But my community can’t. My community doesn’t even know what good or bad exposure limits are to all of these contaminants.”

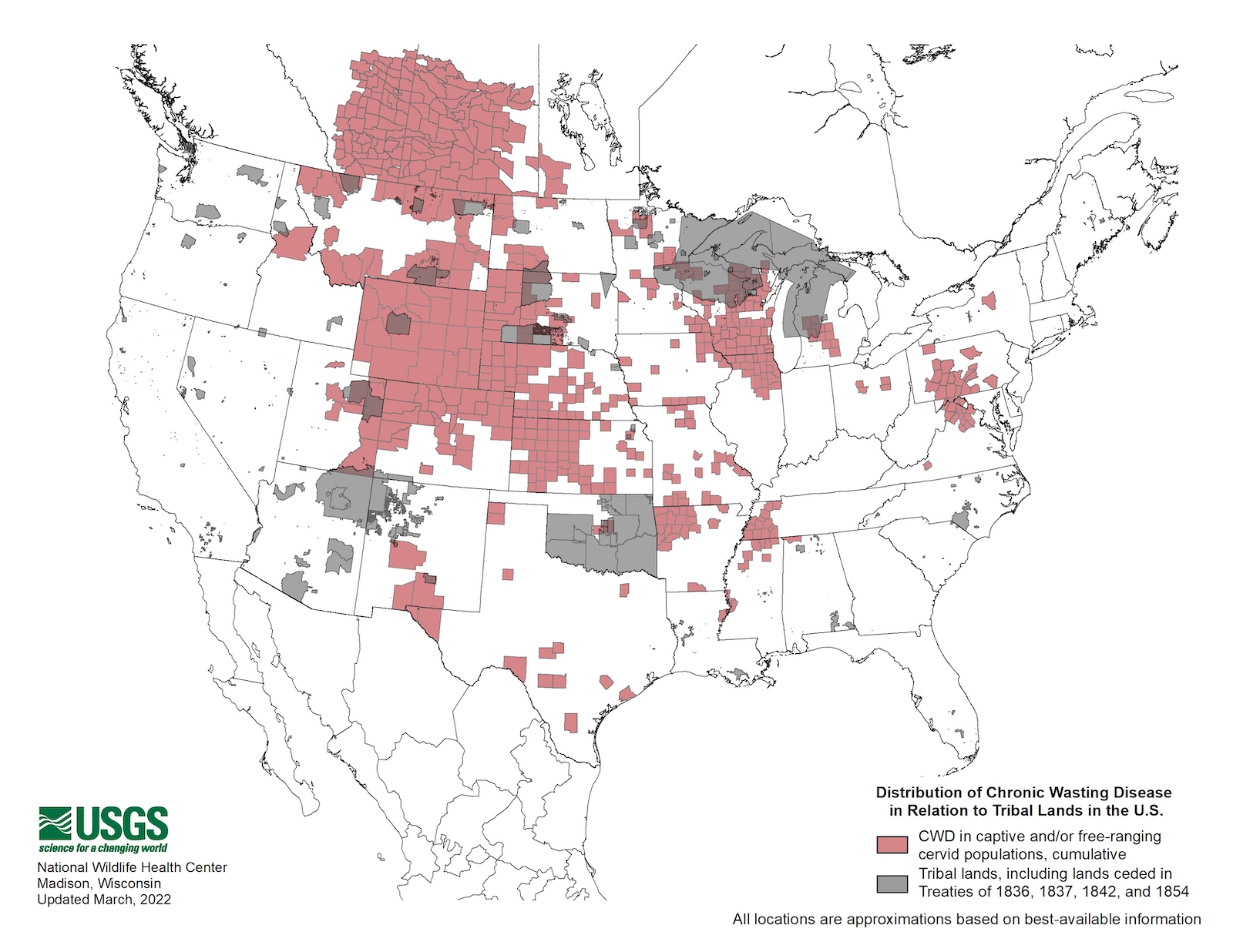

And there’s a new threat on the horizon, one that further imperils the tribe’s reliance on the environment. The dogs have been brought out to the reservation this year to track down environmental contamination, but next summer, they’ll hunt for traces of an even worse-understood health hazard: chronic wasting disease.

In the winter of 2020, a Blackfeet hunter named Charley Wolf Tail shot and killed a white-tailed deer on his property and, because he had heard warnings about a strange illness percolating in deer in Montana, sent the animal’s lymph nodes to the Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks department for testing. The nodes turned up positive for chronic wasting disease, or CWD, an illness caused not by a virus or a bacteria, but by a baffling phenomenon in the natural world: a misfolded protein, or a “prion.”

One prion can infect the proteins in healthy cells by forcing them to fold, too, creating a chain reaction that produces a series of tiny holes in the brains of the hoofed ruminants that are unlucky enough to come across it. The prions create a mushy, spongy texture in the organ. Outwardly, the animals waste away for no discernible reason. Chronic wasting disease is often referred to as “zombie deer disease” because the creatures afflicted with it end up dazed and haggard, walking in aimless circles until they die. CWD could lead to mass die-offs in deer and elk populations on the reservation — whose meat Blackfeet depend on for survival. And experts still don’t know if the illness can spread to humans.

The federal government has detected CWD in 30 states. The deer shot by Wolf Tail is the first documented case of CWD on the reservation. If it spreads, it could further upend the Blackfeet way of life. “Because we live so close to the land and because we’re subsistence hunters,” Calling Last said, “if there is a human impact from CWD, it’s going to be to the tribal people.”

Once CWD establishes itself in a given area, it’s nearly impossible to eradicate. A bacteria or a virus, like the coronavirus, can survive on a surface for a limited amount of time before it dies. A prion can exist, in theory, forever. “Once it’s in the environment, it’s there sort of indefinitely,” Cory Anderson, a CWD expert at the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, told Grist.

Some studies show that grasses and other plants can absorb prions from animal saliva and feces and, in turn, impart the disease to other animals that eat the plants. “We use plants for our ceremonies, our sweat lodges, our food, and our tea,” Calling Last said. “If those plants have prions in them, what does that mean for us?”

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania have determined that dogs can detect CWD prions in deer feces in the lab. But experts have never attempted putting working hounds on the hunt for CWD in the field. Next summer, WD4C plans to conduct an in-the-field canine search for the prions, right here on the Blackfeet reservation.

It’s a new day in Glacier County and the sun is high in the sky as Calling Last turns right on a long, winding dirt road that leads to a ranch-style house in the middle of a large field. She’s taking the Working Dogs for Conservation crew to one last site on the reservation before this year’s research trip is over — a place she calls “ground zero.”

The women clamber out of their trucks and put on shoes they’ve been saving for this site, their “dirty” shoes. So little is known about the misfolded proteins that cause chronic wasting disease, and Calling Last and the Working Dogs team aren’t taking any chances. When they’re done surveying here, they’ll rinse their shoes with bleach and clean the dogs’ paws with disinfecting wipes in order to prevent rogue prions from hitching a ride back to Missoula with them.

Wolf Tail, the hunter who shot the deer, steps out of his house and walks toward the parked cars. He knows why the researchers are here. He’s just as worried about CWD as they are and is glad to help them prepare for next year’s prion surveys. “Hunting is my way of life,” he said, standing in the driveway and holding his dog, a terrier-pug mix named Uno. Herds of deer amble past Wolf Tail’s front porch every day. He scans them religiously now, looking for sick animals. “It’s something that’s definitely been in the back of my mind now, since the testing,” he said.

There’s no way Calling Last can search the entire reservation for prions. There are too many acres and not enough money or dogs. But she has figured out a way around those obstacles by making an educated guess. The way chronic wasting disease works is still shrouded in mystery; some ruminants get the disease after encountering prions, while others are exposed and walk away unscathed. Calling Last thinks the determining factor is immune system function — how healthy an animal is at the time of exposure. She’ll test that theory by having the dogs search for CWD in the same areas where they hunted for environmental contaminants this year.

“The main point of the project is to see whether there is a correlation between these contamination sites and CWD. Like, do animals have lower immune systems because of contamination, and are these animals more likely to get sick?” Vasquez said. In short, there may be an overlap between environmental contamination and CWD, which would mean that protecting the community from one threat also protects it from the other.

Charley Wolf Tail’s house. Grist / Zoya Teirstein

A dead bird floats in the river behind Wolf Tail’s house. Grist / Zoya Teirstein

The otter and mink scat that the dogs find today, at ground zero, will help Calling Last test her hypothesis. Vasquez, a GPS tracking device hanging from a lanyard around her neck and a long leash in her hand, walks to the back of her truck and opens the tailgate. The two rescues peer out at her from their crates.

“Let’s bring Frost out for this one,” Ott says, glancing at the Springer spaniel. Frost lets out a frantic bark at the sound of his name.

“OK,” Vasquez says, opening the door to his crate, “You’re up, bud.”

Vasquez puts a collar and a red vest on Frost, who is standing on the truck bed trembling with excitement. “Free,” she says when he’s suited up, and Frost jumps down from the truck. Vasquez walks around the back of Wolf Tail’s house and down to the stream, Frost bounding a few feet ahead of her. A bright, midday sun is shining. Calling Last, Vasquez, Richards, Ott, and the others who have been running alongside the dogs for three days straight are drained and quiet, slightly diminished by the significance of ground zero. The prions could be lurking anywhere, in the tall grass rippling across Wolf Tail’s backyard or the dark mud that lines the river bank. Frost is unfazed. There’s mink and otter scat to be found, and a squeaky reward to receive.

Vasquez makes him heel and sit before she gives him the command that transforms the excited pup into a laser-focused hunting machine: “Go find,” she says.