During her 2010 Senate confirmation hearings, centrist-liberal Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan famously allowed that “we are all originalists.” In a 2015 interview at Harvard Law School honoring her then-colleague Justice Antonin Scalia, Kagan proclaimed that “we are all textualists now.”

However, in a dissent opinion to the West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency decision, which gutted the Clean Air Act, Kagan wrote: “Some years ago, I remarked that we’re all textualists now. ... It seems I was wrong. The current Court is textualist only when being so suits it.”

What are we to make of Kagan’s change of heart about originalism and textualism? And what does her change of heart tell us about the future of the legal conservative movement?

Originalism and textualism are purportedly neutral methods of constitutional interpretation associated with the Federalist Society and the legal conservative movement that tell us judges must adhere to the original meaning of important laws at the time of their adoption. Originalism concerns itself with the original meaning of the Constitution. Textualism extends its reach to all statutes.

Legal conservatives distinguish originalist and textualist methods from the organic notions of a “living Constitution” associated with the “judicial activism” of liberal judges. The concept of a living Constitution operates from the premise that the Constitution was intended to evolve with changing circumstances and changing times.

On the surface of her remarks at Harvard, Kagan was simply paying homage to Scalia, without a doubt the leading theorist and practitioner of originalist and textualist methods. She was being gracious. But with Scalia, it was always a matter of unrequited love.

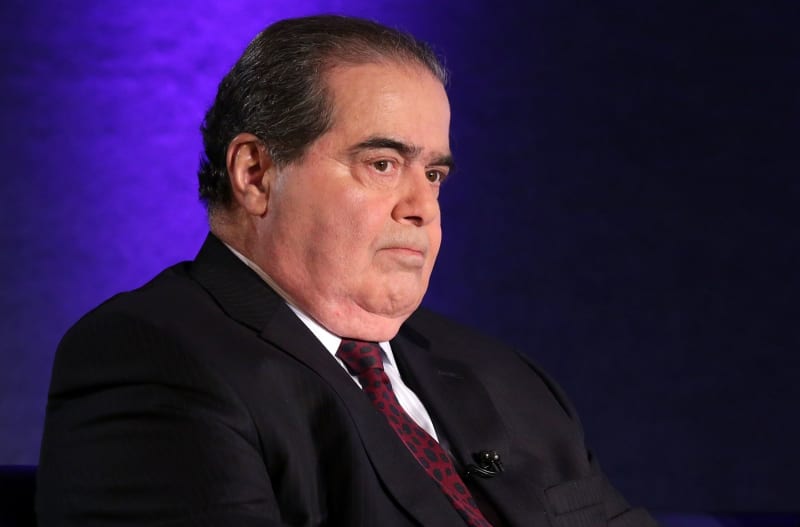

Scalia was astonishingly charismatic. This droll man, lionized by all while alive, was especially beloved for his swagger and humor. However, Scalia was often loath to return this love.

When he was appointed to the Supreme Court in 1986, many assumed Scalia’s “likable personality” would naturally make him perfect in the important role as the court’s swing justice, managing diverse coalitions on challenging cases and gliding the docket forward. But Scalia could not have been less interested in this honored slot on the court. “The originalist has nothing to trade,” he said.

Indeed, Scalia will never be known for writing majority decisions. He actually wrote very few in the last 20 years of his time on the court, as he cultivated a reputation for withering dissents in which he made no concessions to anyone.

Scalia’s devotional Catholic spirit inflected his jurisprudence. But his brash, combative personality was from outside the folds of the church’s formal teachings. Quite simply, Scalia relished going it alone because it conformed to the darkest alleys of his faith. Scalia was by nature a hunter, only fully himself when stalking his prey.

Scalia claimed that his “living Constitution” opponents often voiced counter-majoritarian opinions, even when purporting to reflect the common values of their own time. But Scalia’s own dissents — on matters such as voting rights, gun rights, abortion, same-sex marriage, free speech and religious freedom — were by definition counter-majoritarian, betraying moral and political preferences barely concealed by the threadbare language of the Constitution.

The complexities of Scalia’s personality allowed him to contain and, in some measure, resolve these tensions between legal reason and moral fervor. But even as the liberal Kagan honored Scalia’s originalist and textualist methods while he was living, her recent demurrals indicate that she believes conservatives have become less respectful of these methods since Scalia’s death nearly seven years ago.

Harvard constitutional law professor Adrian Vermeule, for one, has in recent years aided the cause of the authoritarian national conservative movement by promoting his own decidedly anti-originalist and morality-infused theory of “common good constitutionalism.” Taking cues in some respects from Donald Trump, Vermeule and other national conservatives have repudiated the constraining effects of originalism and textualism on behalf of a strong and active state that ensures “the ruler has the power needed to rule well” and that finds the law in the original moral meaning of the Constitution.

The Supreme Court itself has also moved into uncharted territory via the morally punishing natural-law philosophical perspectives of Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito and Neil Gorsuch. They eschew the formally neutral aims of originalist and textualist methods for the substantive moral imperatives they understand to lie beneath the floorboards of the Constitution.

The conservative Federalist Society is smack dab in the middle of this tension between the fetish of the text and fetish of the state. Conflicts related to this turmoil will likely feed a struggle for the soul of the Republican Party heading into the 2024 presidential election. They already are undermining and threatening the Federalist Society’s allegedly central mission of upholding the integrity of the Constitution.

Scalia held these forces at bay. In his absence, emerging philosophical and ideological battles within the legal conservative movement suggest that originalism and textualism have not prevailed for so many decades as legal theories because they were intrinsically superior to other ways of interpreting the law.

Rather, they prevailed because they were attached to the cult of personality surrounding Scalia.

____

ABOUT THE WRITER

Peter Schwartz is a writer based in the Pacific Northwest. He has a doctorate in political philosophy from the University of California at Berkeley, taught at the university level and founded an online legal news and data company. He publishes the Substack newsletter Wikidworld.

2023/01/03

© Chicago Tribune