By Charles M. Blow

Opinion Columnist

Republicans keep reaping what they’ve sown.

The party’s thoroughly embarrassing inability to choose a speaker of the House after multiple attempts is a crisis of its own creation. Since at least the Barack Obama years, the Republican Party has seen a strengthening of its right flanks, one whose mission was not to produce policy but to prevent progress, one whose tactic was destruction rather than diplomacy.

You could see the beginnings of the current iteration of this political extremism when John McCain picked the woefully unqualified Sarah Palin as his running mate in 2008. She wasn’t highbrow, but she was headstrong. She was the anti-Obama.

During her speech at the Republican National Convention in 2008, she said that she had learned that if “you’re not a member in good standing of the Washington elite, then some in the media consider a candidate unqualified for that reason alone.” But, she continued, “here’s a little news flash for all those reporters and commentators: I’m not going to Washington to seek their good opinion; I’m going to Washington to serve the people of this country.”

Palin exposed a dangerous reality about the Republican base: that it was starving for disruption and spectacle, that it would cheer for anyone who annoyed liberals, that performance was far more important than competence.

Like a virus evolving variants, the Palin fervor channeled itself into the Tea Party movement, which evolved into the Freedom Caucus and manifested among voters as Trumpism.

The party establishment chose to ignore those on the fringe, figuring that the energy they generated could be beneficial, and any damage they did could be mitigated. In any event, they were only a fraction of the members and could always be outvoted.

The problem was that their influence and profiles continued to grow. They learned a lesson born during the Palin years: Spectacle produced fame, which produced power, which produced influence and possibly control.

They began to exert that power. The Freedom Caucus essentially forced the Republican speaker of the House, John Boehner, to resign in 2015 because its members felt he wasn’t forceful enough against Obama. Representative Peter King reportedly said, “To me, this is a victory for the crazies.”

But those “crazies” were far from finished. They refused to support Kevin McCarthy for the speakership then because he was Boehner’s No. 2 and because Republicans were fuming that he slipped and told the truth about the Benghazi investigation: that it was a political witch hunt designed to hurt Hillary Clinton’s presidential prospects.

Some of that old disdain for McCarthy has no doubt lingered and is being manifested in this week’s failed votes to make him speaker.

Donald Trump became Exhibit A for the synergy of fame, power and influence the Republican base craves when he broke through the establishment firewall in 2016 and gave his supporters what they wanted: an unbridled political anarchist, an unapologetic white nationalist.

During the Trump era, the Marjorie Taylor Greenes of the party became rock stars among the base, even if they were jokes among their colleagues. Their success has made the term “fringe” a poor way to describe them. In many ways, they are the Republican Party.

All the while, too few mainstream Republicans objected to their antics and offenses. Paul Ryan, who became speaker in 2015 when the Freedom Caucus made it clear that its members wouldn’t support McCarthy, knew Trump was a problem but said little to push back against him until Ryan left office.

As Tim Alberta reported in Politico Magazine in 2019, Ryan made the conscious decision when he was speaker not to “scold” Trump but to “help the institutions survive,” to “build up the country’s antibodies” and put “the guardrails up.” He wanted, he said, “to drive the car down the middle of the road” without letting it “go off into the ditch.”

Ryan, like many other mainstream Republicans, thought that by biting his tongue, putting his head down, and doing his best to work with Trump and do his job, he was protecting the country.

But that silence read as acceptance, not only of Trump but also of the burn-it-all-down members of the party in Congress. Now, that group has grown strong enough to prevent a House speaker from being elected on the first ballot for the first time in 100 years.

And they are getting precisely what they want: more headlines, more airtime, more spectacle and therefore more power.

They aren’t interested in governing, but rather in teasing the growing urge among the Republican base to throw a wrench in the gears.

More on the race for House speaker

Opinion | Michelle Goldberg

Leopards Eat Kevin McCarthy’s Face

Jan. 4, 2023

Opinion | Spencer Bokat-Lindell

What Will Republicans Do With Their House Majority?

Jan. 4, 2023

Charles M. Blow joined The Times in 1994 and became an Opinion columnist in 2008. He is also a television commentator and writes often about politics, social justice and vulnerable communities. @CharlesMBlow • Facebook

The Political Profile of McCarthy’s Detractors Most from uncompetitive districts

A Commentary By Kyle Kondik

Most from uncompetitive districts; recent primary results helped build the anti-McCarthy coalition

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

-- This article is being published following the adjournment of the House on the afternoon of Wednesday, Jan. 4 after the body failed to elect a speaker on 6 roll call votes held Tuesday and Wednesday. The House was scheduled to return at 8 p.m. eastern on Wednesday.

-- The 21 Republicans who did not vote for Kevin McCarthy on every roll call generally, but not exclusively, come from uncompetitive districts. They almost all appear to have at least some connection to the House Freedom Caucus, the group of hardline conservatives.

-- Some recent choices by GOP electorates helped strengthen what would become this anti-McCarthy coalition.

-- The longer this goes on, the more need there may be for a creative solution, like we saw in Pennsylvania’s state House speaker election on Tuesday.

Profiling the McCarthy opposition

The U.S. House of Representatives did something on Tuesday that it had not done in a century -- go to a second ballot for speaker. Then it went to a third, without resolution. Votes 4, 5, and 6 happened on Wednesday, with almost exactly the same results as those held on Tuesday. No clear resolution is in sight as of this writing.

The vast majority of the Republican conference dutifully supported House Republican leader Kevin McCarthy (R, CA-20) on all of the votes, but 19 of the 222 Republicans voted against McCarthy each time. With the House at a 222-212 Republican majority -- there is a single vacant Democratic seat, VA-4 -- McCarthy needs 218 votes to win, assuming that everyone votes and votes for a speaker candidate by name (as opposed to voting “present”). A 20th Republican defected on the final vote held on Tuesday, Rep. Byron Donalds (R, FL-19). The only change on Wednesday was that Rep. Victoria Spartz (R, IN-5) voted “present” on votes 4, 5, and 6. That reduced the winning threshold from 218, to 217, but it also removed a vote from the McCarthy column. Very subtly, the McCarthy position was weakening -- he started with 203 votes on the first 2 votes, fell to 202 on the third, and then 201 on the fourth, fifth, and sixth. It may be worth noting that McCarthy received more votes in 2021 (209), when Republicans were in the minority, than what he got on any of the votes so far.

The anti-McCarthy forces do not really have a clear alternative. The non-McCarthy votes were splintered on the first roll call. They then went to Rep. Jim Jordan (R, OH-4), who himself backs McCarthy, on votes 2 and 3. The insurgents then backed Donalds, the Tuesday vote-switcher, on votes 4, 5, and 6.

The entire Democratic caucus, with 212 votes, backed House Democratic leader Hakeem Jeffries (D, NY-8) on all 6 votes. Though much of the attention was on the Republican side, the Democratic unity was also notable: in each post-2010 vote, former Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D, CA-11) always had at least a few detractors.

How this gets resolved remains a mystery, but while we wait, we thought we’d take a closer look at the 21 Republicans who did not back McCarthy on all of the votes.

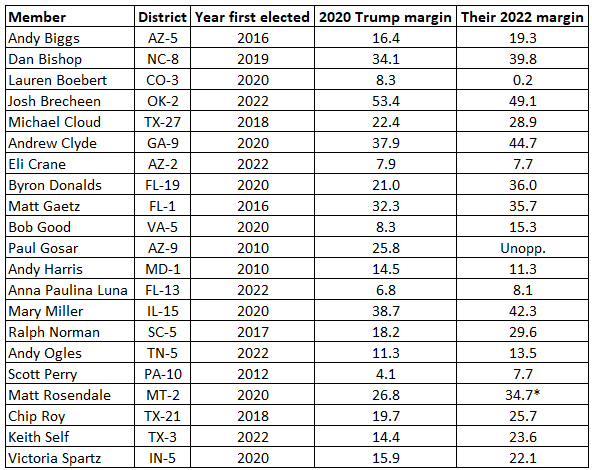

Table 1 lists them alphabetically -- just like the roll call to which our eyeballs have been glued over the past couple of days -- and notes when they were first elected, Donald Trump’s margin in their districts in the 2020 presidential election, and their own electoral performance in 2022.

Table 1: Electoral profile of Republicans who did not support McCarthy on all votes

Notes: All voted for someone other than Kevin McCarthy on all 6 speaker votes conducted on Tuesday and Wednesday, with the exception of Rep. Byron Donalds (R, FL-19), who supported McCarthy on the first 2 ballots but not on subsequent votes, and Rep. Victoria Spartz (R, IN-5), who backed McCarthy on the first 3 ballots but voted present on subsequent votes. *The “their 2022 margin” column shows how much these Republicans won by in November 2022 over the person who finished in second place in their districts. In all but one instance, the second-place finisher was a Democrat; Rep. Matt Rosendale’s (R, MT-2) nearest rival in a 3-way race was an independent.

Sources: Biographical Directory of the United States Congressand Crystal Ball research for when members were first elected; Daily Kos Elections for 2020 presidential results by district; Associated Press, Decision Desk HQ, and official state sources for 2022 district results.

Nearly all of those who did not support McCarthy on every roll call are either members of the House Freedom Caucus, a group of hardline Republicans, or are politically adjacent to the Freedom Caucus. The House Freedom Fund, which is associated with the Freedom Caucus, supported some of the new members-elect who voted against McCarthy. The exact membership of the Freedom Caucus is a little hazy, as the group does not have an official public roster, but in going through these individuals, we found Freedom Caucus membership or connections for almost all of them. Spartz appears to be the single exception, although she has been supported by the Club for Growth, an outside conservative group that has often served as an anti-establishment force within the GOP political universe.

Many are newer to the House, and some of the more veteran members were part of previous protests against McCarthy. For instance, Reps. Andy Biggs (R, AZ-5), Paul Gosar (R, AZ-9), and Scott Perry (R, PA-10) backed Jordan for speaker as a protest vote in the 2019 speaker election won by Pelosi. They are among the 21 non-McCarthy voters now.

All of those who did not consistently vote for McCarthy were elected to districts that voted for Donald Trump for president in 2020, as well, although Trump’s performance in these districts varied widely, and a handful of them are on the fringe of the competitive House battlefield.

Rep. Lauren Boebert (R, CO-3), who has quickly become one of the biggest rabble-rousers in the House, only very narrowly won reelection in 2022 in her Trump +8 district that covers much of western Colorado. She really sticks out as the biggest 2022 electoral underperformer on this list. Joe Biden, or whoever the Democratic nominee is, may not carry her district in 2024 -- it usually has a mild but stubborn Republican lean -- but Democrats would like to give Boebert another tough race after her close call last year.

The others who won districts that Trump only carried by single digits are House Freedom Caucus Chairman Perry, who represents a Republican-leaning but arguably blue-trending Harrisburg-based district and has had competitive elections in recent years, particularly in 2018; Rep.-elect[^] Anna Paulina Luna (R, FL-13), who won by 8 points in a gerrymandered, more Republican version of the seat that former Rep. Charlie Crist (D) left behind to run what became an uncompetitive challenge to Gov. Ron DeSantis (R-FL) last year; Rep.-elect Eli Crane (R, AZ-2), who defeated former Rep. Tom O’Halleran (D) last year after Arizona’s independent redistricting commission made his sprawling northern Arizona district markedly more Republican; and Bob Good (R, VA-5), whose district includes Charlottesville and the University of Virginia -- but also much of the redder Southside region -- won a competitive election in 2020 before winning more easily in 2022.

Many of these other Republicans are in extremely red districts that are uncompetitive in general elections.

There are a number of choices made by GOP voters in this group of districts in recent years that have now made McCarthy’s life harder. What follows is not meant to be an exhaustive list of all the changes in all of these districts. But note the political trajectory in these handful we mention, where harder-line Republicans won out over other Republicans who profile less as troublemakers in a speaker vote:

-- Good unseated now-former Rep. Denver Riggleman (R) in a 2020 convention. Riggleman has since left the Republican Party. Though Riggleman was a member of the Freedom Caucus during his time in Congress, he was not as ideological and socially conservative as his successor has been.

-- Rep. Mary Miller (R, IL-15) defeated now-former Rep. Rodney Davis (R, IL-13) in a member vs. member primary last year. Davis is a mainstream Republican who was friendly with leadership; Miller is much more of a renegade.

-- Boebert ran to the right of former Rep. Scott Tipton (R) in a shocking primary upset in 2020.

-- Rep.-elect Andy Ogles (R, TN-5), who last year won a gerrymandered version of a seat that was previously much more Democratic and centered on Nashville, defeated, among others, former state House Speaker Beth Harwell (R), who we suspect would have been friendlier to House leadership.

-- Rep.-elect Keith Self (R, TX-3) appeared headed to a primary runoff with now-former Rep. Van Taylor (R) last year, but Taylor bowed out immediately after the first round of voting, admitting to infidelity. Taylor, who tried to position himself closer to the center in a somewhat competitive 2020 general election, got 49% in the first round, almost enough to avoid the runoff. Republican mapmakers shored up this northern Dallas-area suburban/exurban seat in redistricting.

While the votes are not directly comparable to this one, Riggleman, Davis, Tipton, and Taylor all voted for McCarthy in the 2019 speaker vote (it’s fair to note that some of those who are not backing McCarthy now nonetheless backed McCarthy in that previous vote). And McCarthy would probably still be in trouble even if some of these districts had made different choices in recent years. But we thought it was worth pointing out how the changing composition of the Republican conference’s membership helped bring us to this point, where a GOP House leader has thus far proven unable to unify his conference in a speaker vote.

So the House’s business of choosing a speaker is unfinished as of this writing (following House adjournment on Wednesday afternoon). The longer this drags on, the more potential there may be for a creative solution.

We saw a couple such instances in the states yesterday.

In Ohio, Democrats -- deep in the minority -- ended up helping deny the state’s House GOP from picking its preferred candidate for speaker (Democrats and some Republicans backed a different Republican instead).

More interestingly, Pennsylvania Democrats and some Republicans came together yesterday to elect a Democrat (who says he will govern as an independent) as speaker in the narrowly-divided chamber. Democrats won a 102-101 majority in November, but 3 vacancies in Democratic-won districts gave Republicans a nominal 101-99 edge to start the session.

The likeliest outcome here is that the Republicans eventually figure this out and elect a speaker with just Republican votes. But we must reiterate that we are in essentially uncharted history here, at least in modern times.

Endnote

[^]Because members have not been sworn in yet, which happens after a speaker is chosen, technically everyone elected to the House is a “Rep.-elect” as opposed to a “Rep.” right now. For clarity’s sake, we are referring to members who were elected prior to November 2022 as “Rep.” and members elected in November as “Rep.-elect.” But we wanted to note this distinction. It is a wild time. If you’re curious about the state of the House right now, and some of these distinctions in this limbo, speakerless period, we recommend following congressional procedure expert Matt Glassman on Twitter.

Kyle Kondik is a Political Analyst at the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia and the Managing Editor of Sabato's Crystal Ball.

See Other Political Commentary by Kyle Kondik.

See Other Political Commentary.

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports. Comments about this content should be directed to the author or syndicate

The former Libertarian congressman was in the Capitol Wednesday drumming up a Hail Mary quest to become speaker of the House.

MATT WELCH |

1.5.2023

REASON.COM

(Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call/Newscom)

As the House of Representatives Wednesday erupted in the kind of chaotic energy one normally associates with far-flung parliaments during Question Time, there was a familiar face sitting with a wry smile next to his old friend Rep. Thomas Massie (R–Ky.): The former five-term congressman from Grand Rapids, Michigan, Justin Amash.

Amash, who was elected each time as a Republican but then during his last term disaffiliated from the GOP and eventually became the first sitting Libertarian in congressional history, was not there just to watch it all burn down—he is offering himself up as perhaps the unlikeliest candidate for speaker of the House in an already unlikely 118th session of Congress.

"I think I'm a great compromise candidate, so why not do it?" Amash said last night on a taping of The Fifth Column podcast, which I co-host along with Kmele Foster and Michael Moynihan. "I'm a former member. I know what's going on. I know what the problems are in Washington. I understand why the House doesn't function properly. So I think it makes sense to put my name out there.

Amash throughout his tenure and into his post-congressional career has been almost monomaniacally focused on the increasingly dysfunctional process for producing legislation on Capitol Hill. It has been his main topic of conversation in Reason interviews, in constituent town halls, with me at LibertyCon in October, with Robby Soave yesterday morning on Rising, and again last night on the podcast.

"I've never been shy about the fact that I'd like to be speaker of the House," he said. "That's not like something that's just popped up now…. I've always said the one position I really would like to have is speaker of the House. And the reason I'd like to have it is because I think I would do a good job, and I would do a good job precisely because I want to go and do what the speaker of the House is supposed to do: Open up the process. I get a thrill from that."

He continued: "Other people get a thrill from going and getting their substantive legislation passed…which is very difficult these days, by the way, because it's all top down, so you have to hope the speaker is going to put it on the floor. I get a thrill from having our government work the way it was intended under our constitutional system. It makes me excited because I love this country, I love liberty, I love our constitutional system, I think we have the best country on the face of the earth. I think we have an amazing Constitution, and it is a real shame that we don't use it."

Amash, who as the co-founder of the House Freedom Caucus challenged the leadership bids of former GOP speakers John Boehner and Paul Ryan, had unflattering things to say about leading speaker candidate Rep. Kevin McCarthy (R–Calif.).

"I served with him for a decade, and I saw what he is. He's not a trustworthy person," Amash said. "He's the most creature-of-Washington politician you can have. Like, Boehner was an institutionalist—for all of his faults, Boehner had some, you know, romanticized vision of Washington. Now, he wasn't great at it, he made a lot of mistakes. I had lots of fights with Boehner, I tried to oust Boehner from the speakership. But when it comes down to it, Boehner at least had some vision of Washington as a place where ideas go to get discussed and debated and you produce some product…. Paul Ryan was a policy guy. Now, he didn't really get his policies to the finish line, but he cared about policy. McCarthy, on the other hand, cares only about power. That's it. He's not interested in policies, he doesn't know much about policy. If you asked Kevin McCarthy about a piece of legislation, he would not really know much about it. He's not that guy, he doesn't care, he's not an intellectually curious person. I don't think he's that bright, honestly. I mean, no offense to him, but he's not a particularly bright person."

As of early Thursday afternoon, McCarthy had lost a seventh bid to become speaker. Amash suggested that the 20 consistent holdouts, some of whom are his friends, have a specific personality issue with the Californian—they don't trust him even a little bit.

"He's just a guy who's about power first, and he'll do whatever it takes to maintain power," he said. "And that's why the 20 members don't trust him. It's why I don't trust him, because they know what he is and they know what he'll do. He'll betray them to the extent that he's made any promises to them, he'll betray them the first chance he gets, and then lie about it. He has no problem doing that. He's a compulsive liar. Always has been."