Greenhouse gas concentrations further increased in 2022, finds analysis of global satellite data

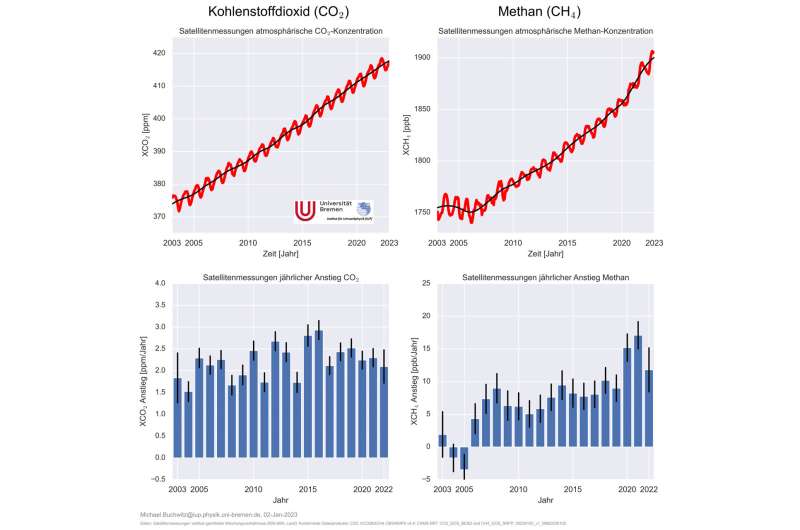

Preliminary analyses of global satellite data by environmental researchers at the University of Bremen show that atmospheric concentrations of the two important greenhouse gases carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) continued to rise sharply in 2022. The increase in both gases is similar to that of previous years. However, the increase in methane does not reach the record levels of 2020 and 2021.

The Institute of Environmental Physics (IUP) at the University of Bremen is a world-leading institute in the field of evaluation and interpretation of global satellite measurements of the greenhouse gases carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) and other atmospheric trace gases that are of great importance for climate and air quality.

The institute leads the GHG-CCI greenhouse gas project of the European Space Agency's Climate Change Initiative (ESA) and provides related data to the European Copernicus Climate Change Service C3S and the Copernicus Atmospheric Monitoring Service CAMS. The latest Copernicus communication on greenhouse gases (see link below) is based on satellite data and analysis provided by IUP.

"The methane increase remains very high in 2022 at about 0.6%, but below the record levels of the past two years. Our guess for this is that on the one hand there have been more emissions, but at the same time the atmospheric methane sink has decreased. At just over 0.5%, the CO2 increase is similar to that of previous years," says environmental physicist Dr. Michael Buchwitz, summarizing the initial results.

Greenhouse gas measurements since 2002

Time series of greenhouse gas measurements from space begin in 2002 with the SCIAMACHY instrument on the European environmental satellite ENVISAT, proposed and scientifically leg by the University of Bremen. These measurements are currently being continued by Japanese (GOSAT and GOSAT-2) and American (OCO-2) satellites, among others.

The satellites measure the vertically averaged mixing ratio of CO2 and CH4. These measurements are referred to as XCO2 and XCH4, and they differ from the commonly reported measurements of near-ground concentrations. The data are reported in parts per million (ppm) for CO2 and parts per billion (ppb) for CH4. An XCO2 concentration of 400 ppm means the atmosphere contains 400 CO2 molecules per one million air molecules. "Methane increased by 11.8 ppb in 2022, CO2 by 2.1 ppm," Buchwitz said.

CO2 increases almost uniformly—in contrast to methane. In the years 2000 to 2006, the methane concentration was stable on average. Since 2007, however, methane has been rising (again), with particularly high rates of increase in recent years. The record levels in 2020 and 2021 are likely associated with a COVID-19-induced increase in the methane sink, but also with an increase in methane emissions.

"Unfortunately, there are still many gaps in our knowledge of the diverse natural and anthropogenic sources and sinks of methane and other greenhouse gases," Buchwitz says. "It is therefore still necessary to make optimal use of and further improve the existing system for global monitoring of climate-relevant parameters."

Provided by Universität BremenNASA cancels greenhouse gas monitoring satellite due to cost

Feds release bleak 2022 climate change data: Oceans warm, global temps among hottest on record

In one announcement after another this week, a grim accounting emerged of the world's extreme weather and climate disasters in 2022

The science leaves "no doubt" about the impacts of the warming climate, Bill Nelson, administrator of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, said during a briefing Thursday. "Sea levels are rising. Extreme weather patterns threaten our well-being across this planet."

The nation's two federal agencies charged with weather and climate observations said in 2022:

- Ocean heat reached a new high

- Arctic sea ice was second lowest level ever recorded

- Europe saw its second warmest year on record, but much of western Europe was the warmest ever

But when it comes to extreme weather and the impacts of climate change, there's no place like home. The U.S. led the world again last year in extreme weather events and disasters, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said on Tuesday.

Oceans get even warmer and saltier

The world's oceans—which absorb more than 90% of the world's excess heat—were again the hottest on record last year.

"Year after year we are breaking records for ocean heat content," Michael Mann, a climate scientist at the University of Pennsylvania, tweeted Wednesday. Mann was one of a team of 16 international researchers who published a paper Wednesday detailing last year's record ocean heat.

The hotter and saltier oceans are critical indicators of "profound alterations" taking place in energy and water cycles, the scientists wrote. "The inexorable climb in ocean temperatures is the inevitable outcome of Earth's energy imbalance, primarily associated with increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases."

If not for the large storage capacity of the oceans, the world would have warmed a lot more already, said Russell Vose, chief of the analysis and synthesis branch for NOAA's National Centers of Environmental Information.

World temperatures again among warmest on record

NASA and NOAA agreed global average temperatures in 2022 were among the warmest on record, with their data and calculations coming to slightly different conclusions.

Temperatures would have been even higher last year without La Nina keeping things cooler in the Pacific, said Gavin Schmidt, director of NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies.

- It's been 46 years since the Earth had a colder-than-average year.

- NASA put the global average temperature at 1.6 degrees above the baseline for 1951-1980 or fifth warmest, tied with 2015.

- The European Commission's Copernicus website also ranked the year 5th warmest.

- NOAA ranked 2022 the sixth warmest at 1.55 degrees above a baseline set between 1901-2000. It does not yet include the Arctic in its calculations.

- La Nina likely contributed a .06 degree Celsius cooling effect on global average temperatures, Schmidt said.

There's almost a 100% chance that 2023 will also be among the top 10 warmest years on record, Schmidt said. And with conditions in the central Pacific Ocean potentially flipping to an El Nino, he and Vose said 2024 could be a contender for warmest year on record.

If the warming continues, the average temperature in a single year could soon top the 1.5 degree Celsius level the world hoped to avoid with the Paris Agreement, Vose said. "There's actually a 50-50% chance that we have one year in the 2020s that maybe jumps above 1.5."

Schmidt guessed the first year with 1.5 degrees warming will be an El Nino year, probably in the early 2030s, but, he said, the world may still be two decades away from sustained warming above 1.5 degrees.

18 billion-dollar disasters in US

"In the U.S. we have consistently had the highest count and the largest diversity of different types of weather and climate extremes that lead to billion dollar disasters," said Sarah Kapnick, NOAA'S chief scientist said Thursday.

The 18 billion-dollar disasters last year were the third most on record, behind 2020 and 2021. They included Hurricane Ian, the mega-drought in the west and a massive snowstorm across much of the country in December.

With a total cost of $165 billion, the 18 disasters made it the third most costly year on record behind 2017 and 2005, the years when Hurricane Harvey and Hurricane Katrina made landfall in the U.S.

At least 474 deaths were reported last year as a result of the billion-dollar disasters.

Hurricane Ian was the costliest disaster of 2022, with estimated damages so far at $112.9 billion.

How did US weather in 2022 compare to previous years?

It was:

- The 27th driest year on record overall.

- The fourth driest year on record in Nebraska.

- The ninth driest in California, thanks to wetter than average conditions during the past two months.

- Alaska's 16th warmest year and fourth wettest year.

- An above average year for tornadoes, with 1,331.

(c)2023 USA Today

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.