two women astronauts in space shuttle holding hardware

A new book explores the astronaut class that permanently changed human spaceflight at NASA.

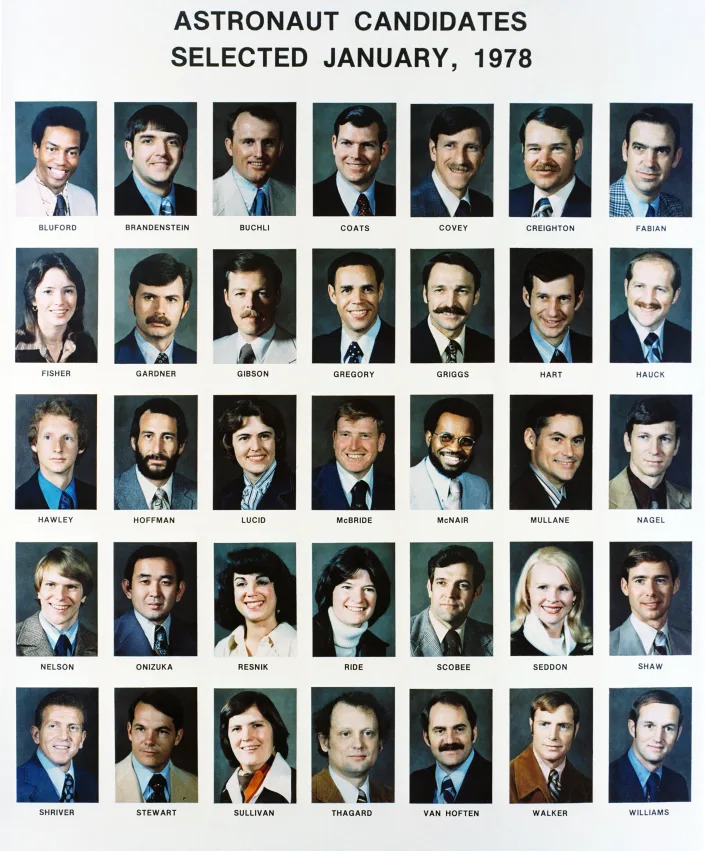

"The Thirty-Five New Guys," as the 1978 astronaut class called itself, brought unprecedented diversity to the previously all-white, all-male astronaut corps. That class included the first female astronauts, among them Sally Ride, who in 1983 became the first American woman in space. Also included were the first African-American astronauts, such as the first flyer of that group, Guion "Guy" Bluford, and Ellison Onizuka, who became the first Asian-American to reach space.

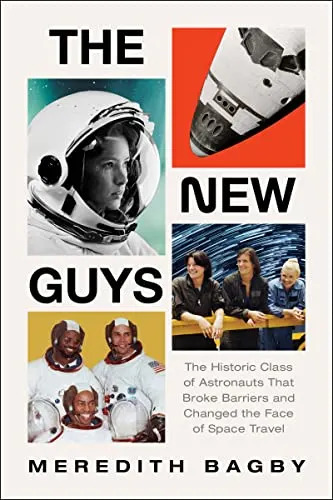

"It was a little bit like a mystery search. You have to find all these really cool pieces of information and put them together," author Meredith Bagby said of the five-year research process that resulted in the book "The New Guys: The Historic Class of Astronauts That Broke Barriers and Changed the Face of Space Travel", which will be published on Tuesday (Feb. 7) by William Morrow. You can check out Space.com's take on the best space books for more options ahead of the release.

Bagby's book shows that NASA undertook that diversity-boosting process only after facing immense pressure from Congress — and that the benefits to the astronaut corps were incalculable.

"The program was strengthened by hiring diverse people," Bagby said. "Diversity actually brings greater success on missions, and greater success of the organization. Having people with different points of view come together and democratize information and treat each other equally actually turns out to be a really good thing for success."

Related: Men, women and Mars: How gender diversity Is key for success on the Red Planet

The New Guys: The Historic Class of Astronauts That Broke Barriers and Changed the Face of Space Travel (Meredith Bagby, Feb. 7, 2023)

The 1978 NASA astronaut class included the first American women, the first African Americans, the first Asian-American, and the first LGBTQ+ individual. This behind-the-scenes look includes exclusive interviews with the astronauts and/or their family members.View Deal

Numerous studies have pointed to the value of diversity, such as a 2019 analysis by McKinsey across dozens of countries. It found that companies that prioritized gender diversity in management were 25% more likely to have better-than-average profitability. The public sector also benefits: Today, NASA identifies diversity as aligning with values of integrity, teamwork and excellence, which the agency deems "central to mission success."

But the conversation around diversity was different in the era of the 1978 astronaut class. Certainly, NASA had diversified somewhat from the late 1950s and early 1960s, when it sought experienced (white) male test pilots to join the astronaut corps.

But the agency was also famous for rebuffing more than a dozen highly qualified female pilots from early space missions; those women were later known as the Mercury 13, in a nod to the first set of NASA human spaceflights in the Mercury program. Many women in crucial ground roles were also put in the background, such as talented Black female mathematicians and engineers later known as "Hidden Figures" in tribute to their success in flying space missions safely.

Related: 'Hidden Figure' Katherine Johnson tells her own story in young readers' book

NASA hired male scientist-astronauts in 1965, although it didn't fly the first of them (Harrison Schmitt) until Apollo 17, the final mission of the Apollo program, in 1972. Schmitt was a trained geologist but was only reassigned from the canceled Apollo 18 flight after the scientific community lobbied NASA for his inclusion.

The astronaut recruitment for 1978 was the first in nearly a decade, in anticipation of frequent space shuttle missions. It came with celebrity flair, as Black "Star Trek" actress Nichelle Nichols ("Uhura" on The Original Series) stepped in to lead publicity for the campaign. The result was 35 new astronauts: six women (including Jewish-American Judith Resnik), three African-Americans and one Asian-American, Onizuka.

Some "New Guys" met with tragedy, however, including Onizuka, Resnik and fellow class members Dick Scobee and Ronald McNair. The four flew on mission STS-51L, the last flight of Challenger with seven astronauts on board. All seven lost their lives when the shuttle broke apart shortly after liftoff on Jan. 28, 1986. NASA made numerous technical and operational redesigns before resuming shuttle program launches in 1988.

That crew's legacy is remembered warmly in the book, which features exclusive interviews with family members and friends to recreate the astronauts' experiences and feelings while at NASA.

The book also shows the 1978 class in general as a turning point in NASA history, when the agency began to expand its astronaut corps to more types of people. Some diversity was unintentional; Ride's LGBTQ+ status was revealed only after her death in 2012, making her the first known in that community to ride to space as well.

Related: This Pride, be inspired by Sally Ride's legacy

A montage of individual images of the 1978 astronaut class at NASA.

The book includes a tapestry of reminiscences from the 35 "New Guys." For example: Black astronaut Ron McNair grew up in the segregated south, only the third generation of his family to live free of slavery; the book recounts the literal railroad tracks separating white and Black communities in his hometown of Lake City, South Carolina.

Anna Lee Tingle turned down a prestigious medical profession appointment even before she was called back for an astronaut interview, while Resnik snuck into Smithsonian Institution offices to ask advice of then National Air and Space Museum director Michael Collins, who flew on the historic Apollo 11 moon mission with Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin.

Bagby found these accounts through talking with astronauts and their family members, reading diaries with family members' permission, and spending time with retired NASA personnel at places like Frenchies Italian Restaurant, a popular community hangout in Houston. (A big early help was George Abbey, the circumspect yet legendary director of flight crew selection during the era of "The New Guys.")

"It just takes time to get to really know the person ... what did they eat for breakfast? How did they feel in that moment?" Bagby said. "I felt very close to all the people I interviewed, and it was really just a wonderful process."

Elizabeth Howell is the co-author of "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022; with Canadian astronaut Dave Williams), a book about space medicine. Follow her on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.