“Shocking Findings” – Painstaking Study of 50-Plus Years of Seafloor Sediment Cores Has Surprise Payoff

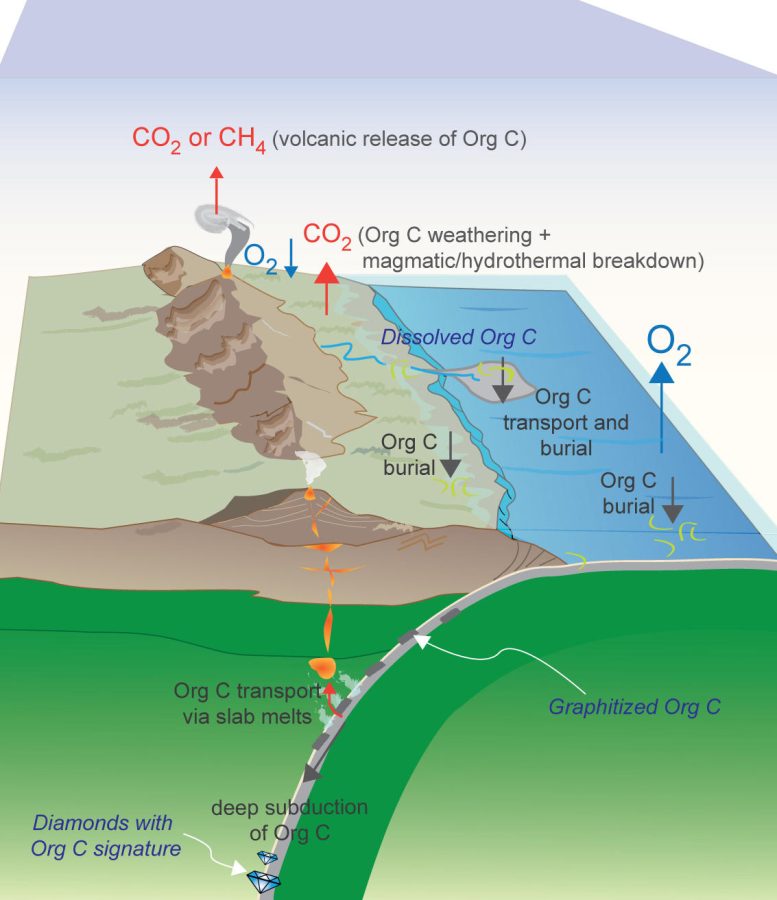

A schematic depiction of the burial and deep subduction of organic carbon. Credit: R. Dasgupta/Rice University

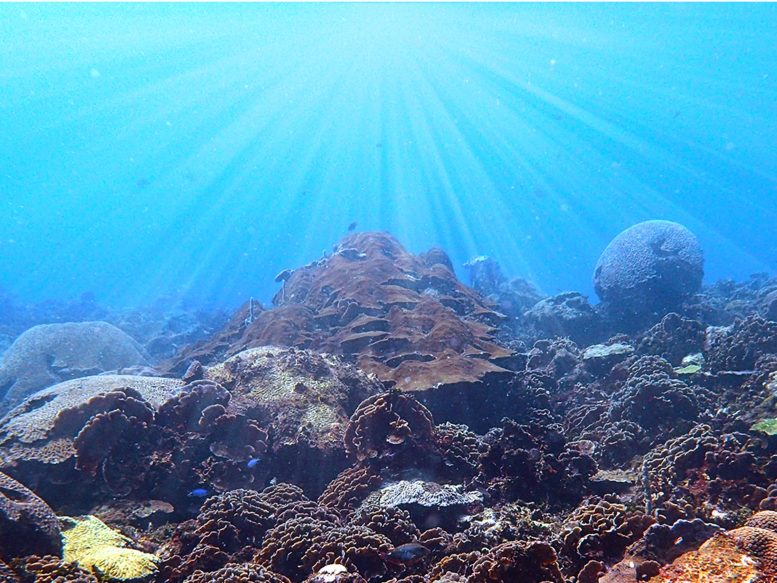

Rising global temperatures are leading to a decrease in the amount of organic carbon being deposited in the ocean floor.

An international group of researchers meticulously collected data from over 50 years of oceanic scientific drilling expeditions to carry out a groundbreaking study of organic carbon that sinks to the ocean floor and is drawn deep into the earth.

According to their study, published recently in the journal Nature, global warming may result in a decrease in the burial of organic carbon and a rise in the amount of carbon released back into the atmosphere. This is due to the potential effect of higher ocean temperatures in boosting the metabolic rates of bacteria.

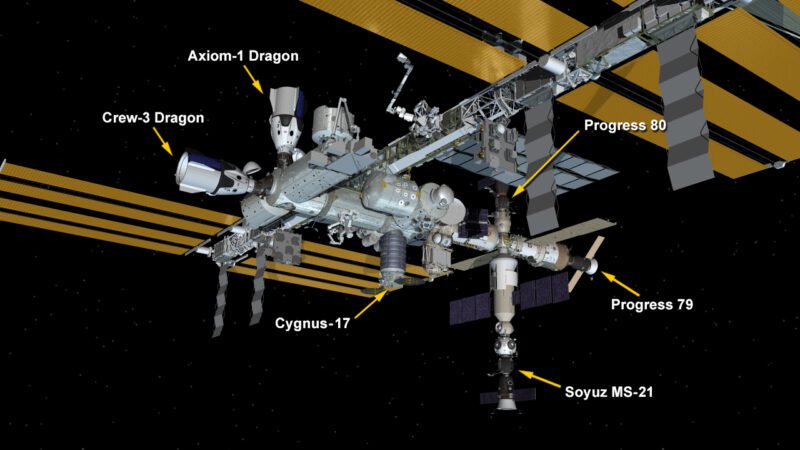

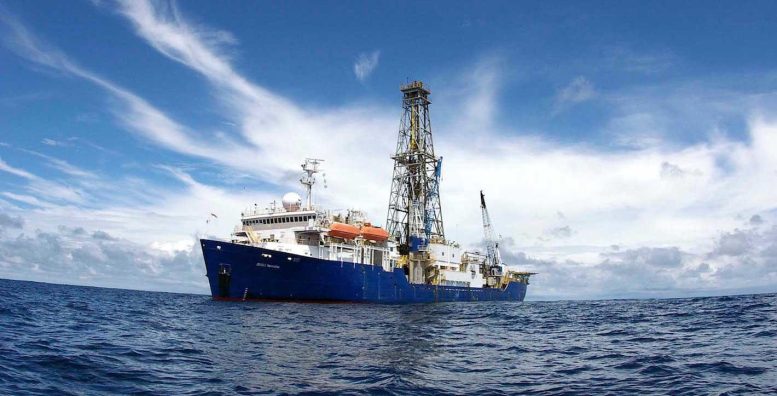

Researchers from Rice University, Texas A&M University, the University of Leeds, and the University of Bremen analyzed data from drilled cores of muddy seafloor sediments that were gathered during 81 of the more than 1,500 shipboard expeditions mounted by the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) and its predecessors.

Their study provides the most detailed accounting to date of organic carbon burial over the past 30 million years, and it suggests scientists have much to learn about the dynamics of Earth’s long-term carbon cycle.

The JOIDES Resolution is a scientific research vessel operated by Texas A&M University for the International Ocean Discovery Program that drills into the ocean floor to collect and study core samples. Credit: International Ocean Discovery Program

“What we’re finding is that burial of organic carbon is very active,” said study co-author Mark Torres of Rice. “It changes a lot, and it responds to the Earth’s climatic system much more than scientists previously thought.”

The paper’s corresponding author, Texas A&M oceanographer Yige Zhang, said, “If our new records turn out to be right, then they’re going to change a lot of our understanding about the organic carbon cycle. As we warm up the ocean, it will make it harder for organic carbon to find its way to be buried in the marine sediment system.”

Mark Torres is an assistant professor in Rice University’s Department of Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Sciences. Credit: Tommy LaVergne/Rice University

Carbon is the main component of life, and carbon constantly cycles between Earth’s atmosphere and biosphere as plants and animals grow and decompose. Carbon can also cycle through the Earth on a journey that takes millions of years. It begins at tectonic subduction zones where the relatively thin tectonic plates atop oceans are dragged down below thicker plates that sit atop continents. Downward diving oceanic crust heats up as it sinks, and most of its carbon returns to the atmosphere as carbon dioxide (CO2) from volcanoes

Scientists have long studied the amount of carbon that gets buried in ocean sediments. Drilled cores from the ocean floor contain layers of sediments laid down over tens of millions of years. Using radiometric dating and other methods, researchers can determine when specific sediments were laid down. Scientists can also learn a lot about past conditions on Earth by studying minerals and microscopic skeletons of organisms trapped in sediments.

“There are two isotopes of carbon — carbon-12 and carbon-13,” said Torres, an assistant professor in Rice’s Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences. “The difference is just one neutron. So carbon-13 is just a bit heavier.

“But life is lazy, and if something’s heavier — even that tiny bit — it’s harder to move,” Torres said. “So life prefers the lighter isotope, carbon-12. And if you grow a plant and give it CO2, it will actually preferentially take up the lighter isotope. That means the ratio of carbon-13 to -12 in the plant is going to be lower — contain less 13 — than in the CO2 you fed the plant.”

For decades scientists have used isotopic ratios to study the relative amounts of inorganic and organic carbon that was undergoing burial at specific points in Earth’s history. Based on those studies and computational models, Torres said scientists have largely believed the amount of carbon undergoing burial had changed very little over the past 30 million years

Zhang said, “We had this idea of using the actual data and calculating their organic carbon burial rates to come up with the global carbon burial. We wanted to see if this ‘bottom-up’ method agreed with the traditional method of isotopic calculations, which is more ‘top down.’”

The job of compiling data from IODP expeditions fell to study first author, Ziye Li of Bremen, who was then a visiting student in Zhang’s lab at A&M.

Zhang said the study findings were shocking.

“Our new results are very different — they’re the opposite of what the isotope calculations are suggesting,” he said.

Zhang said this is particularly the case during a period called the mid-Miocene, about 15 million years ago. Conventional scientific wisdom held that a large amount of organic carbon was buried around this interval, exemplified by the organic-rich “Monterey Formation” in California. The team’s findings suggest instead that the smallest amount of organic carbon was buried during this interval over the last 23 million years or so.

He described the team’s paper as the beginning of a potentially impactful new way to analyze data that may aid in understanding and addressing climate change.

“It’s people’s curiosity, but I also want to make it more informative about what’s going to happen in the future,” Zhang said. “We’re doing several things quite creatively to really use paleo data to inform us about the present and future.”

Reference: “Neogene burial of organic carbon in the global ocean” by Ziye Li, Yi Ge Zhang, Mark Torres and Benjamin J. W. Mills, 4 January 2023, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-05413-6

The study was funded by the American Chemical Society’s Petroleum Research Fund. On behalf of the National Science Foundation, Texas A&M has served as the science operator of the IODP drill ship JOIDES Resolution for the past 36 years as part of the largest federal research grant currently managed by the university.